Summary

“In the world there are some weird people,” my high school health teacher said to introduce the lesson. Then she said sex between boys was the main cause of AIDS so we should stay away from homosexuals. That was the only time I heard about LGBT people from a teacher—except when I overheard them making gay jokes.

–Sachi N., 20, Nagoya, November 2015

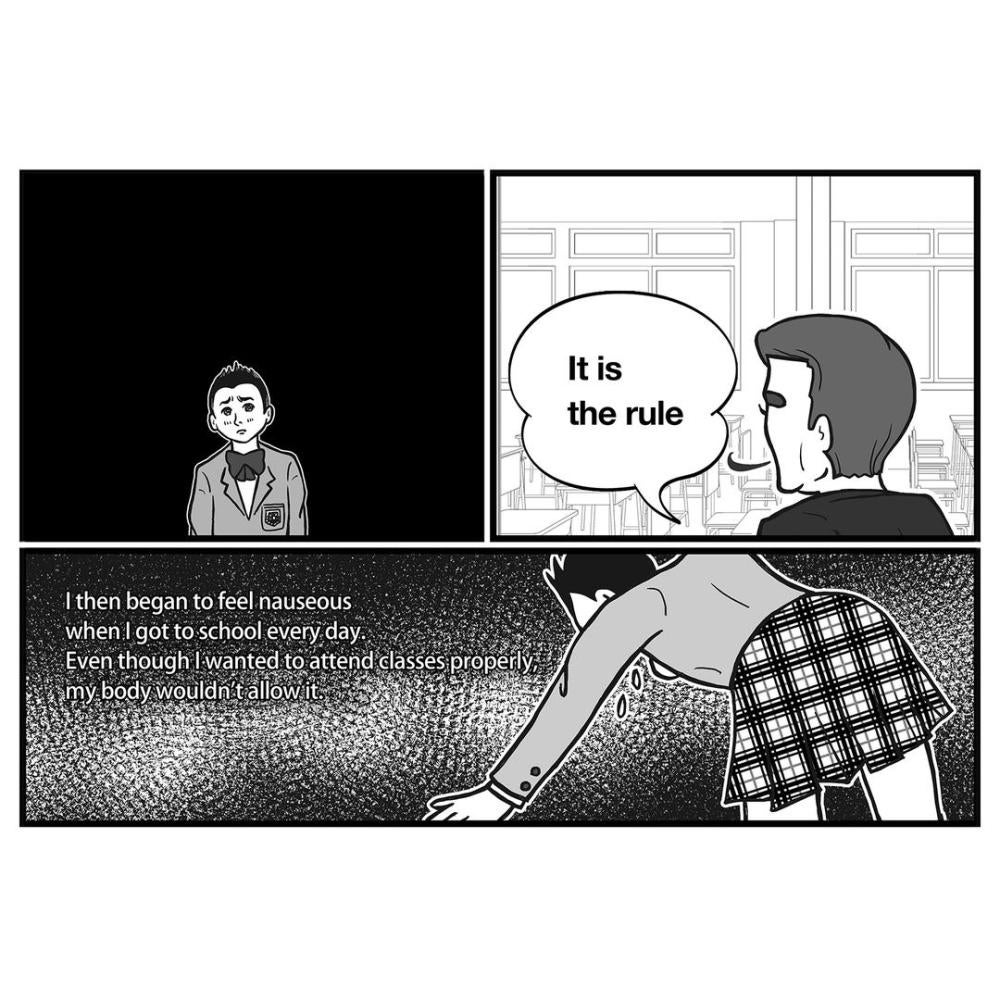

He said, “No, this graduation ceremony isn’t about you. I’m not going to let your selfishness ruin the harmony of this school.”

–Natsuo Z., 18, Fukuoka, recalling a high school administrator’s response to a request to wear the male school uniform, August 2015

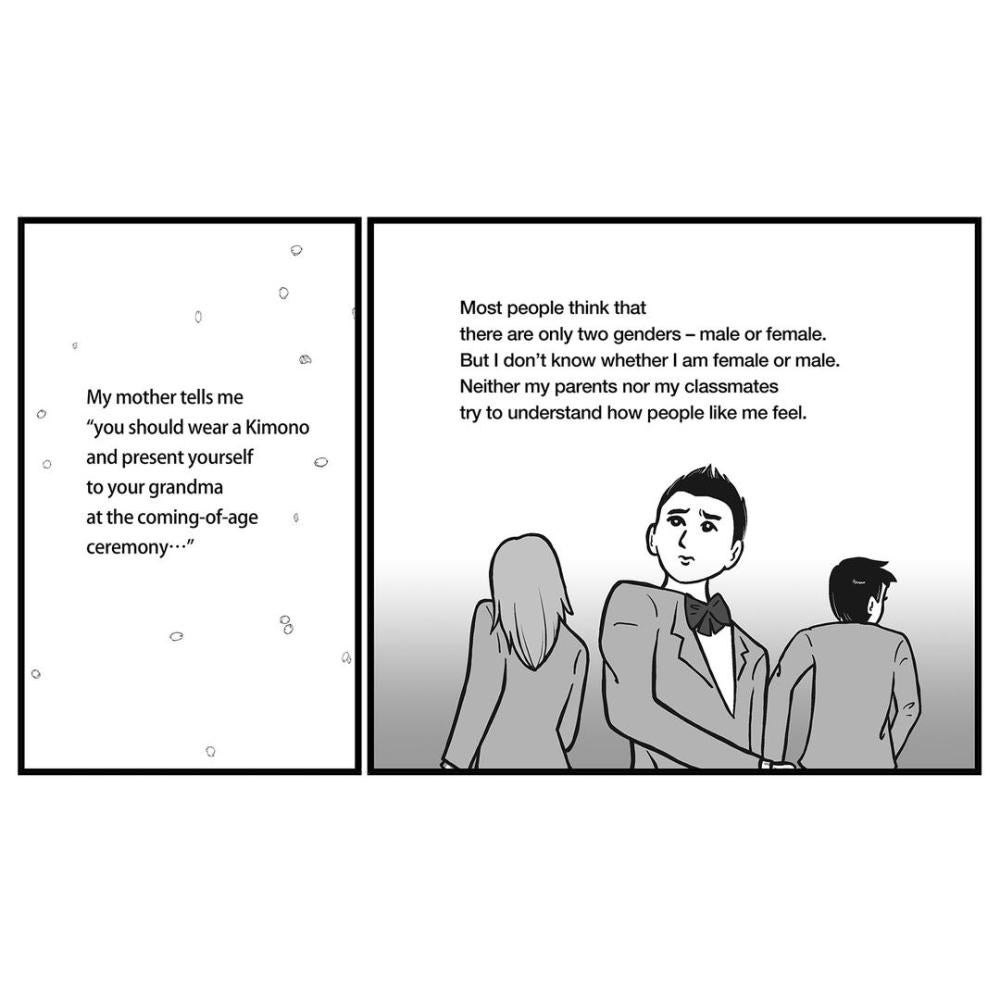

No child's safety or healthy development should depend on a chance encounter with a compassionate adult. In Japan, however, that is often the case for youth who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) or as other sexual and gender minority identities, or who are questioning their sexual orientation or gender identity.

Japanese LGBT children who attempt to report bullying and harassment to school officials play their luck, as the response depends entirely on an individual teacher or school staffer’s personal perspectives on sexual orientation and gender identity. There is no comprehensive training for school staff, and the guidelines that do exist are non-binding suggestions issued in April 2016, which predicate respect and accommodation for gender identity on the diagnosis of a mental disorder.

Based on interviews with more than 50 LGBT students and former students in fourteen prefectures throughout Japan—as well as teachers, officials, and academic experts—this report documents bullying, harassment, and discrimination in Japanese schools based on sexual orientation and gender identity or expression, and the poor record of schools when it comes to appropriately responding to and preventing such incidents.

Human Rights Watch found that despite official statements to the contrary, there are LGBT students in Japanese schools who, due to policy gaps, inadequate teacher training, and weak enforcement mechanisms, are targeted by bullies because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

The Japanese government has failed to institute effective anti-bullying policies that specify the vulnerabilities of LGBT students; adequately train school staff to respond to the needs of LGBT students and hold staff accountable for their actions; or uphold Japan’s international human rights commitments with regard to educational content about sexual orientation and gender identity.

Students in Japan who have questions about gender and sexuality are left in a harmful lurch. Seeking information from official sources such as school libraries may leave them empty handed or with limited information—due, for example, to books that construe all gender identity issues as a mental disorder. Approaching school staff with questions can result in censuring or outright bullying. Even in cases of compassionate and supportive responses, the lack of teacher training means that students are at best faced with improvised knowledge based on teachers’ personal views. The strong cultural desire to “maintain harmony” means that even teachers who do try to support LGBT students can be left, as one former teacher put it, “alienated in their own compassion.”

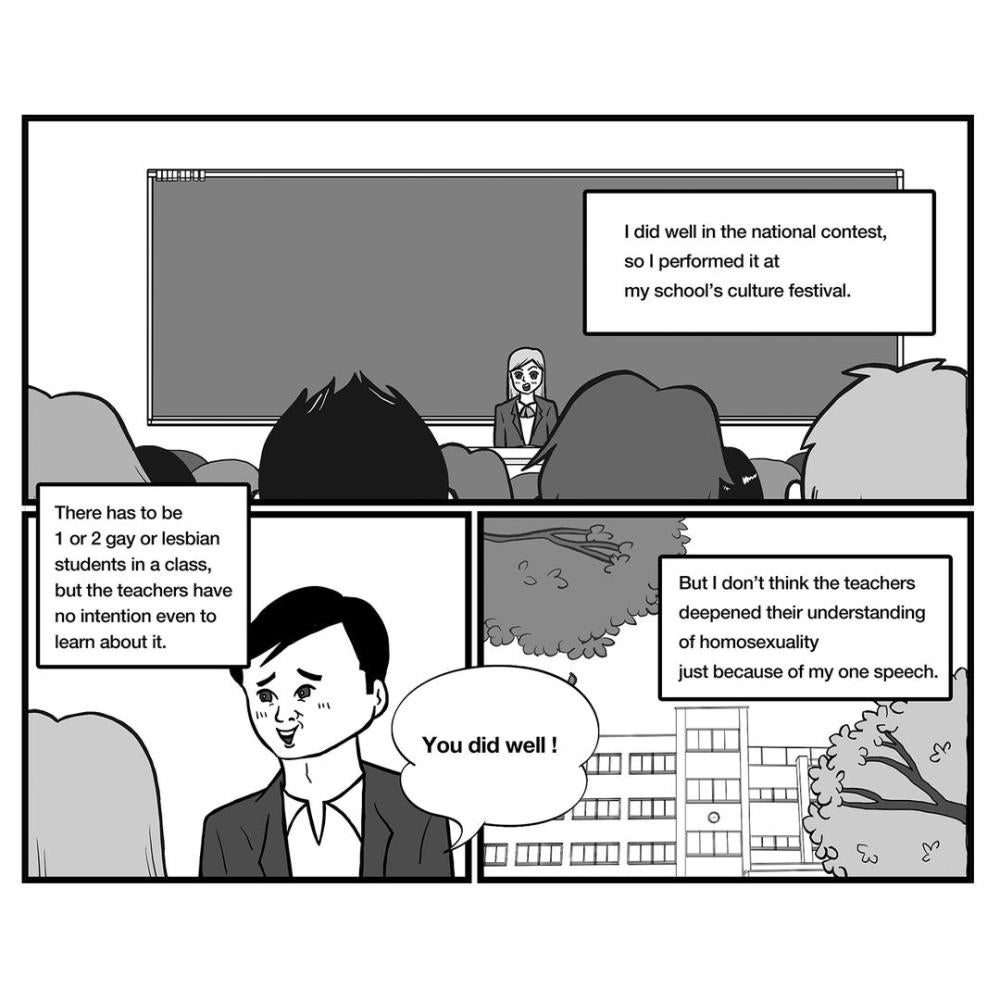

Hateful anti-LGBT rhetoric is nearly ubiquitous in Japanese schools, driving LGBT students into silence, self-loathing, and in some cases, self-harm. The information vacuum combined with pervasive hateful comments from students and teachers alike means sexual and gender minority children in Japan sometimes first struggle with their identities with shame and disgust.

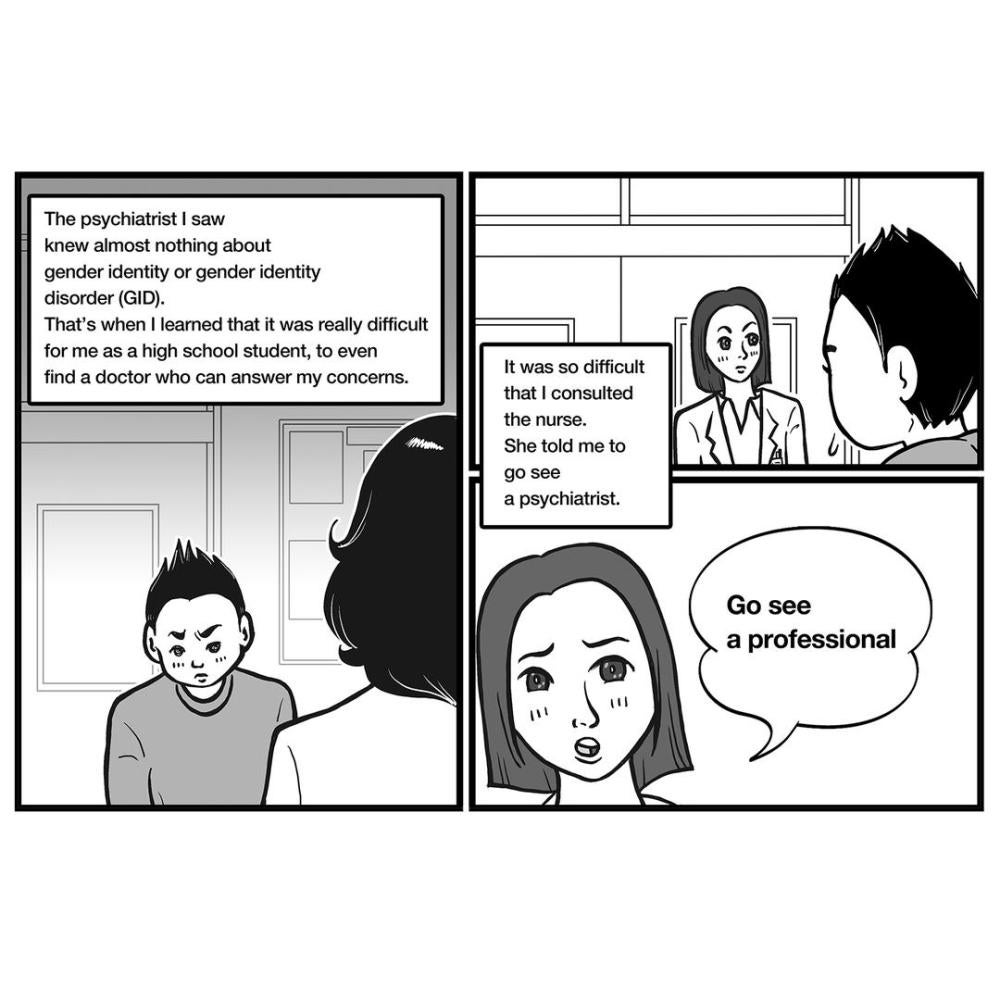

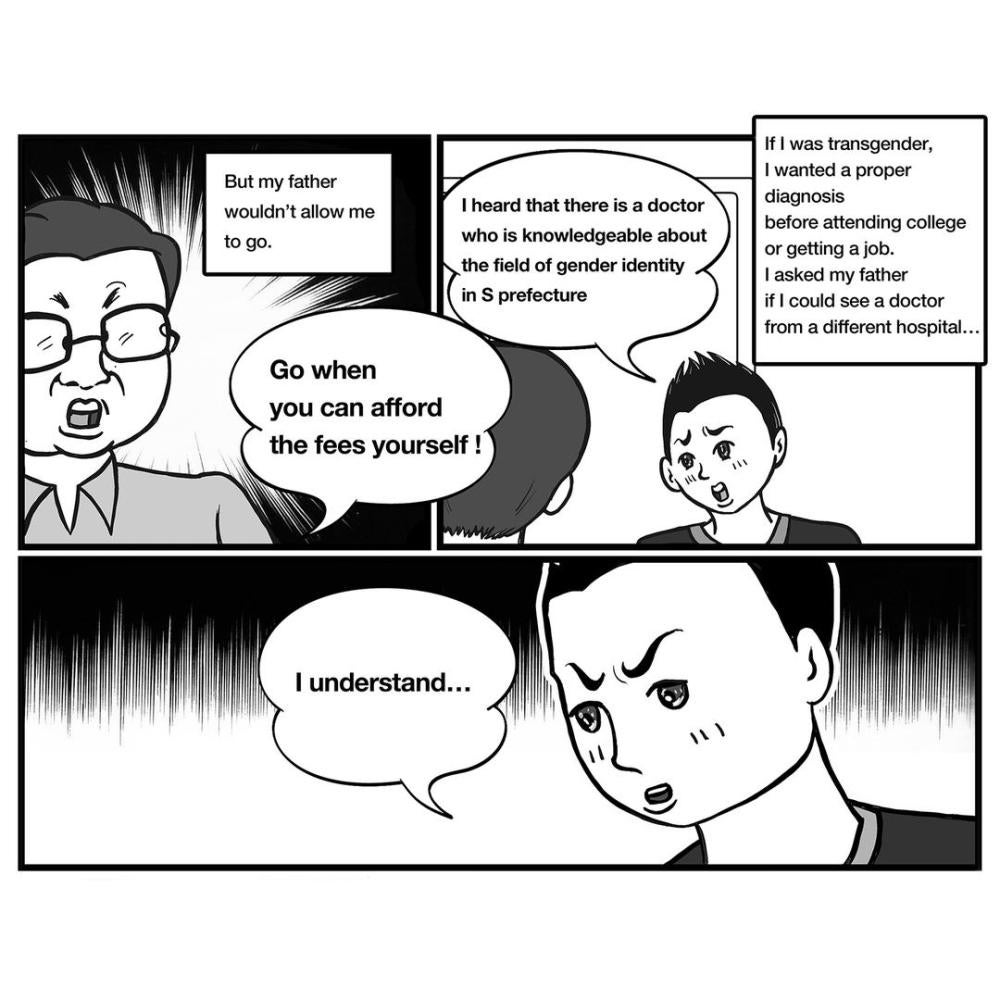

Gender nonconforming children often have no choice but to be diagnosed with gender identity disorder (GID) before they can access education according to their appropriate gender. And regardless of whether children pursue a GID diagnosis, instead of being encouraged to explore and express their identity, they are slotted into a rigid system that mandates further medical procedures as part of the legal recognition process later in life—violating their basic rights to privacy and free expression under international human rights law and medical ethics standards.

Even when schools attempt to support and accommodate students who wish to have their gender identity recognized or who request protection from sexual orientation or gender identity-based harassment, the response can be ephemeral. School officials, while demonstrating care for individual students, remain mired in policy structures that subtly incentivize the maintenance of school harmony over the protection of vulnerable students. Anti-bullying policies remain silent on the specific vulnerabilities and needs of categories of children, including LGBT children.

In a well-known case three decades ago concerning a student suicide following bullying with teacher complicity, a Japanese district court in 1991 ruled that the local government in charge of the school was not liable for the death because the school could not have foreseen suicide of the student as the result of bullying. To its credit, the government has dedicated some political capital to the issue, holding emergency meetings after high-profile cases and drafting policies. But the effective implementation of these policies is elusive as the government remains wed to the theory that “bullying can happen to any child in any school”—a truism that does not acknowledge that structural issues make certain students especially vulnerable to harassment and exclusion.

Japanese schools continue to promote conformity and harmony over rights. The national bullying prevention policy calls bullying a human rights violation, but then promotes moral education on social norms as a bullying prevention measure. The concerns and needs of individual students get lost.

These include issues of rigid gender stereotyping in schools forcing gender nonconforming students to curtail their freedom of expression; a harmful lack of information about sexual orientation and gender identity in both teacher training and school curriculum standards; and pervasive homophobic environments across all types and levels of schools. The government’s role in these abuses or failure to address them can amount to human rights violations.

As the debate over human rights for LGBT people in Japan continues to gain momentum and the national bullying policy comes up for review, the government should sharpen bullying prevention and response measures to specifically enumerate categories of people who are particularly vulnerable to school-based harassment and violence, including LGBT youth.

Governments are obligated to ensure the rights to health, information, and education, and the right to be heard, for all children. Japan has particularly fallen short with respect to transgender and gender nonconforming children. Strict gender segregation in Japan’s schools, enshrined through school uniform policies and gender separation for some activities, can make navigating school life difficult for transgender and gender nonconforming children. Facilities that students can only access according to the gender they were assigned at birth create barriers for transgender children, who also face a discriminatory legal age limit and intimidating medical requirements in accessing gender recognition.

As the Bullying Prevention Act comes under a mandatory three-year review in 2016, the government should consider substantial revisions in line with its human rights commitments, including the right to education. Japan’s government should take this opportunity to refine its anti-bullying policies to bring them in line with its international human rights obligations, including two recent United Nations Human Rights Council resolutions on ending sexual orientation and gender identity-based violence and discrimination that Japan has supported. This will mean identifying and combating the structural causes for bullying, many of which are highlighted in this report.

Recommendations

To the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology

- Specify categories of vulnerable students, including LGBT students, as part of the 2016 review process stipulated in the Bullying Prevention Act.

- Monitor schools for compliance with the principle of non-discrimination, intervene where the policies are failing, and include sexual orientation and gender identity in any data collection tools measuring bullying in schools.

- Work with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to develop and conduct research on school climates for LGBT students in which information is gathered directly from affected populations of children.

- Build on the 2016 Guidebook for Teachers Regarding Careful Response to Students related to Gender Identity Disorder as well as Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, by developing teacher training materials on sexual orientation, gender identity, and human rights, and make such training mandatory for all current teachers.

- Ensure that all university programs for the education and certification of teachers include mandatory training on working with diverse students, including those who are LGBT and those who are questioning their sexual orientation or gender identity.

- Issue a revised directive that clarifying that schools should accommodate students according to their self-declared gender identity without requiring any medical examinations. Schools should ensure that students have full access to education —including school uniforms, lavatories, or documents—without a diagnosis of “Gender Identity Disorder.” This should include access to the lavatory the student is comfortable with, not only gender-neutral or disabled students’ facilities.

- Work with the Ministry of Justice and the Diet to revise Law 111 of 2003 (the Gender Identity Disorder Law), Japan’s legal gender recognition procedure, replacing humiliating mandatory procedures such as sterilization with self-identification criteria for legal gender recognition.

- Include information about sexual orientation and gender identity in the national sex education curriculum based on guidelines set forth by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

To the Ministry of Justice

- Advise Diet members and submit a bill to revise the Gender Identity Disorder Law to bring it in line with Japan’s international human rights obligations and international best practice standards.

To the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

- Update all health care policies that affect transgender people to bring them in line with the World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care-7, standards set by international health and medical experts for health care systems to provide the best possible care for transgender persons.

- In conjunction with the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology’s directive to school boards, issue an urgent directive to psychiatrists and other mental health care professionals clarifying that children are not required to obtain a diagnosis of gender identity disorder in order to access education according to their gender identity.

To Municipal Governments and School Boards

- Institute non-discrimination clauses in local anti-bullying policies that specifically mention sexual orientation and gender identity.

- In line with MEXT’s 2016 Guidebook and in partnership with LGBT NGOs, promptly create programs to conduct teacher training on sexual orientation, gender identity, and human rights, including distribution of resource materials for classrooms and referral instructions for teachers who need extra support.

- Mandate that all teachers undergo training on sexual orientation, gender identity, and human rights, including access to education issues appropriate to the age group the teachers work with.

To the National Diet

- Include in the draft non-discrimination legislation protections for students from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity, as well as the explicit anti-discrimination clause for administrators, teachers, counselors, other school staff, and other employees from discrimination in employment on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted the research for this report between August and December 2015 in fourteen prefectures in Japan.

Researchers conducted more than 100 interviews, including 13 with children under age 18 identified as sexual or gender minorities; 37 with sexual and gender minorities over 18 about their experiences as children; and more than 50 with teachers and other school staff, government officials, lawyers, parents, and academic experts on bullying, mental health, and other related fields.

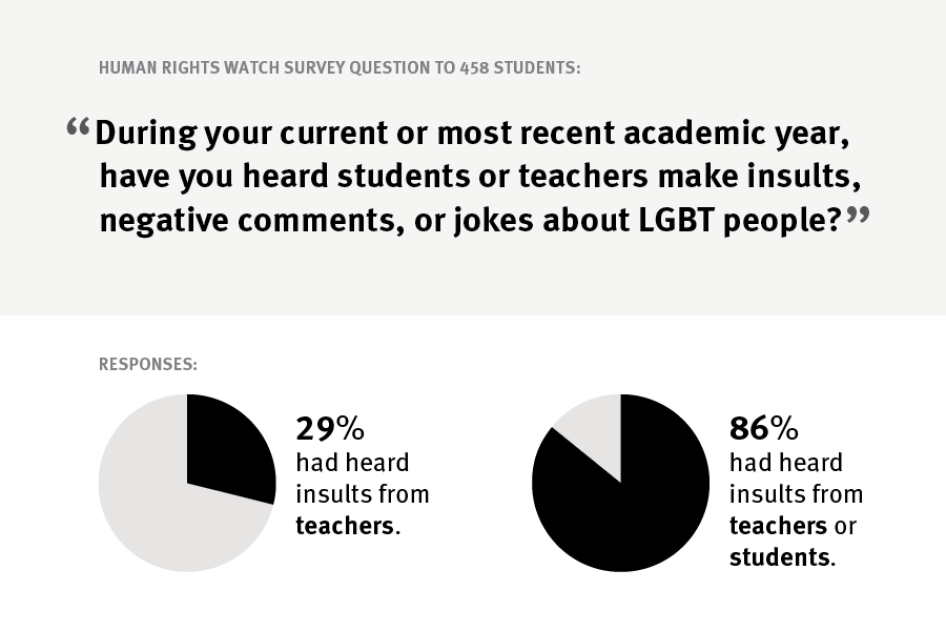

To identify LGBT people who had experienced bullying in school, Human Rights Watch conducted outreach through Japanese NGOs and through an online solicitation form and survey. The survey was used for the purposes of collecting basic data about experiences of bullying, discrimination, and anti-LGBT harassment in schools, which is presented throughout the report, as well as to introduce these topics and invite survey participants to take part in face-to-face in-depth interviews with Human Rights Watch researchers. The survey was distributed on Facebook and Twitter.

Of those who answered the survey, 458 were under 25, which is the sample this report uses to analyze the experiences of LGBT people who were recently in school. Of the face-to-face interviews that were conducted with survey respondents, an overwhelming majority told Human Rights Watch they found the survey on Twitter, and chose to respond to it because it had been tweeted or re-tweeted by one of several reputable Japanese LGBT organizations or celebrities.

No compensation was paid to either survey respondents or those who participated in face-to-face interviews. Human Rights Watch reimbursed public transportation fares for interviewees who traveled to meet researchers in safe, discreet locations. The interviews were conducted in Japanese, with Japanese-English simultaneous interpretation. All interviews with people who experienced bullying in school were conducted privately, with participants being interviewed one at a time. In two instances, a counselor from an NGO that worked with LGBT youth was present at the request of the child. Four interviews were conducted on Skype and LINE, a text and voice messaging smartphone app, per the interviewees’ requests due to restrictions on their ability to safely discuss LGBT and school violence issues, or leave their homes. Some interviews with experts, teachers, and social service providers were conducted in group settings, and Human Rights Watch researchers followed up in private with individuals.

Human Rights Watch researchers obtained oral informed consent from all interview participants, and provided written explanations in Japanese and English about the objectives of the research and how interviewees’ accounts would be used in this report and other related materials. Interviewees were informed that they could stop the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions they did not feel comfortable answering.

In this report, pseudonyms are used for all interviewees except for a small number of adults who strongly preferred that their real names be used.

I. Young and Queer in Japan

In junior high I heard a lot of anti-LGBT jokes from fellow students. I grew up thinking that everyone around me knew of LGBT people as those people it was okay to tease.

–Kiyoko N., 20, Tokyo, November 2015

Most teachers think students who are gender nonconforming are just selfish or arrogant—this is what they tell the kids and this is what the kids come to us asking about. It is so damaging when a kid is struggling already with these feelings, then they are told by a teacher that they are arrogant, then by a psychiatrist that they have a disorder.

–Ai K., LGBT youth counselor, Fukuoka, August 2015

Children and young adults told Human Rights Watch about their childhood attempts to access information and express themselves when they began learning about their sexual orientation and gender identity.

Nearly everyone interviewed said they began to question and explore either their own gender or their romantic attraction to people of the same gender when they were children; some explained that they knew they were not cisgender or heterosexual as young as 5 years old.[1]

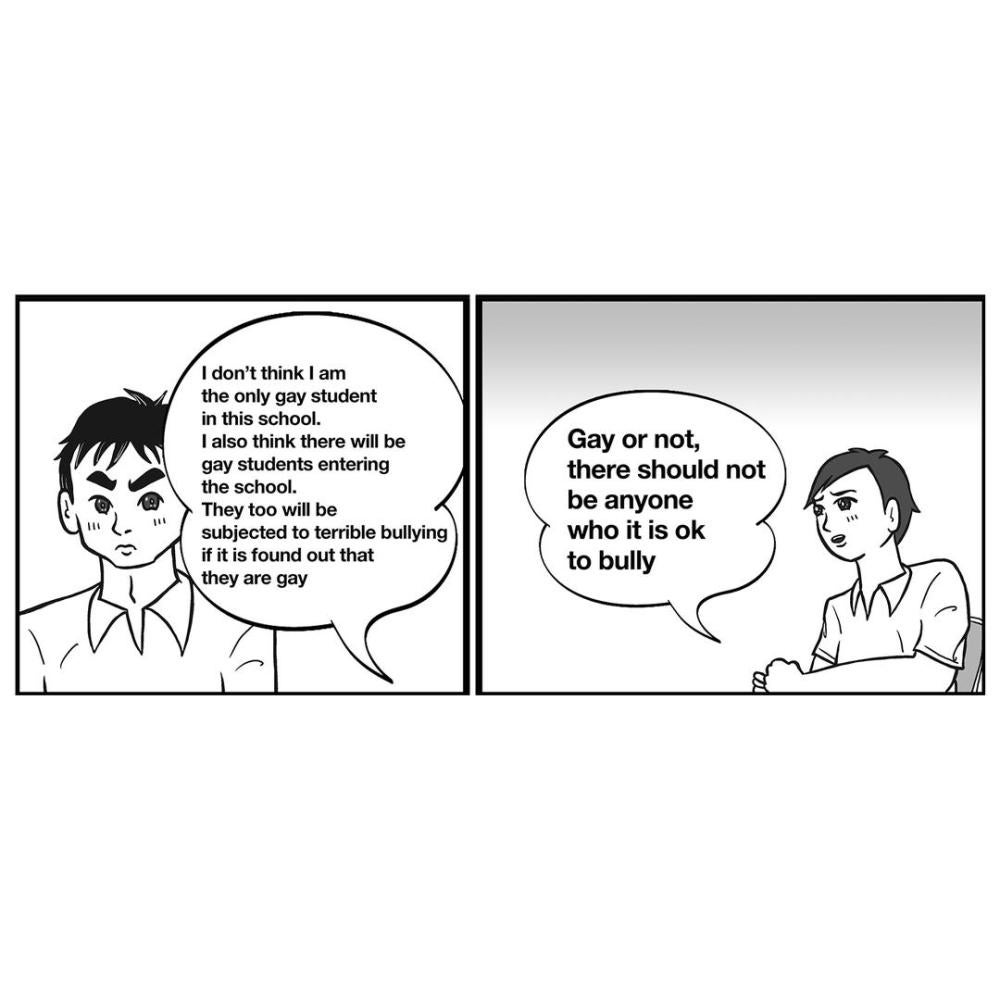

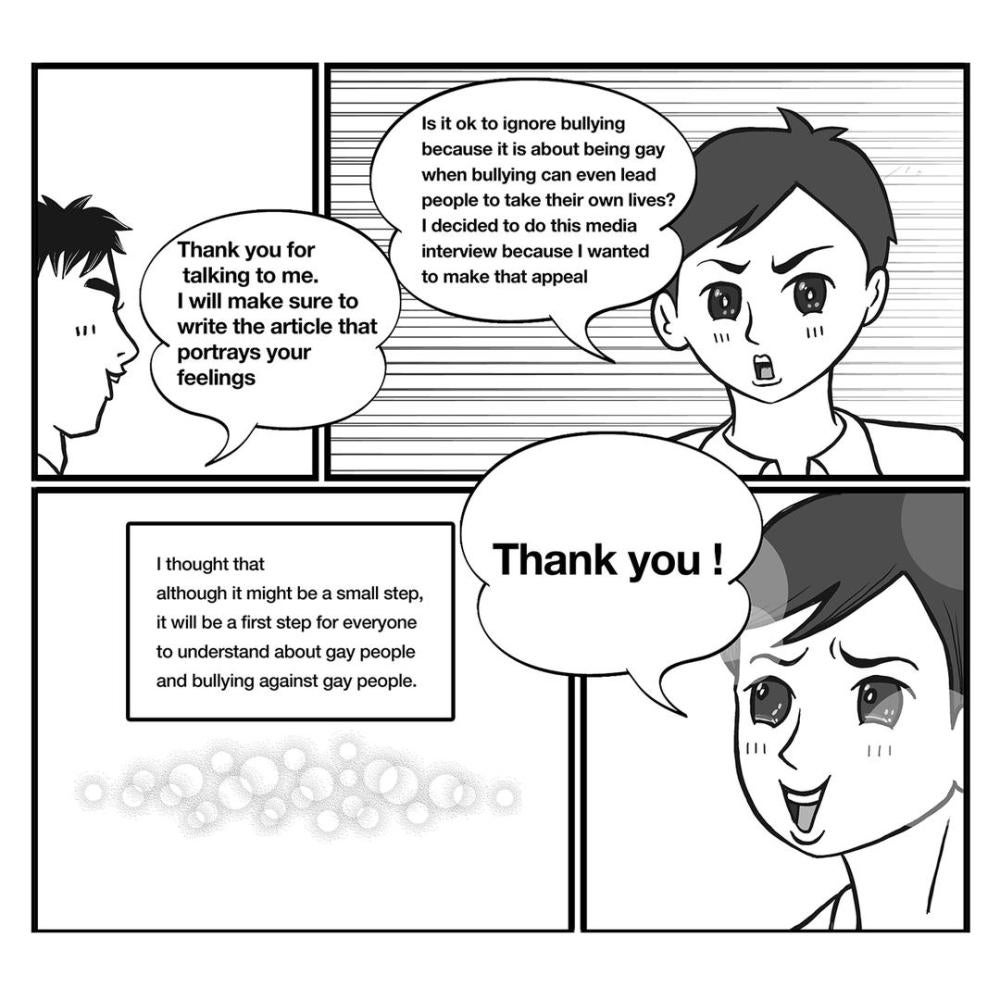

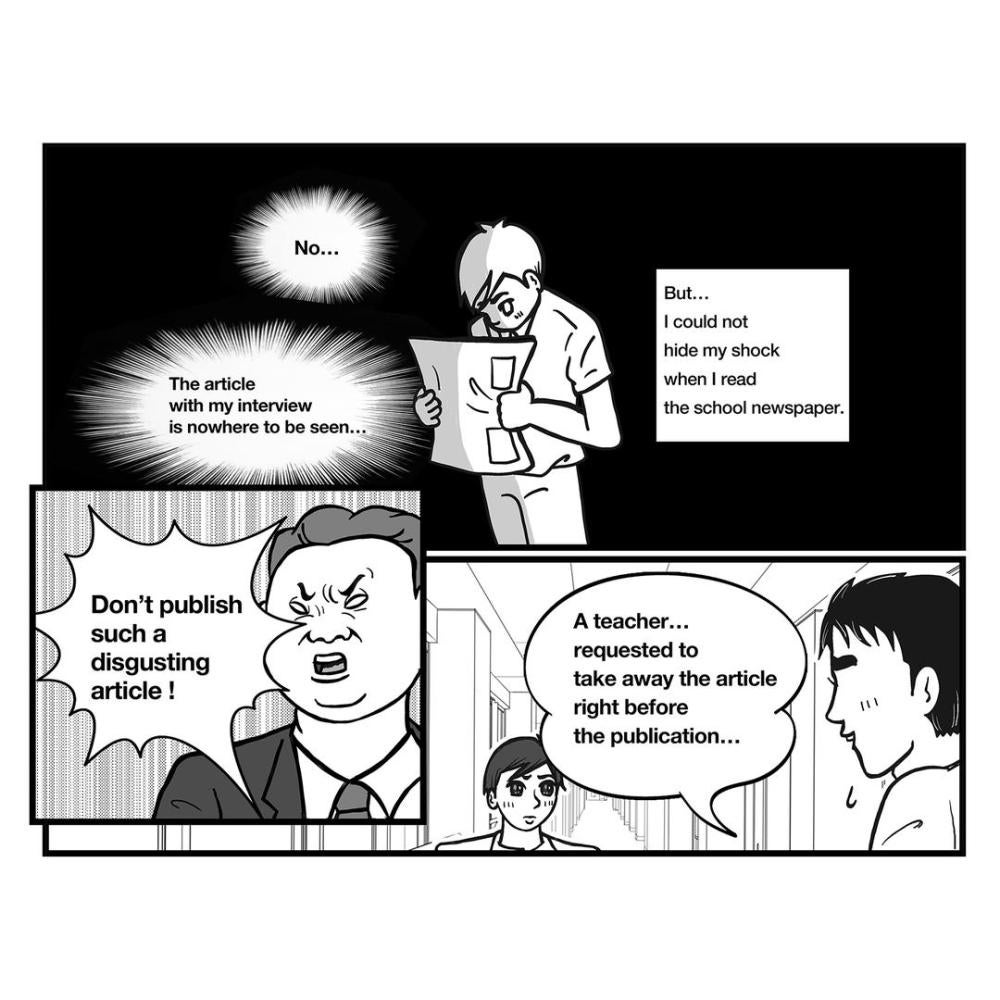

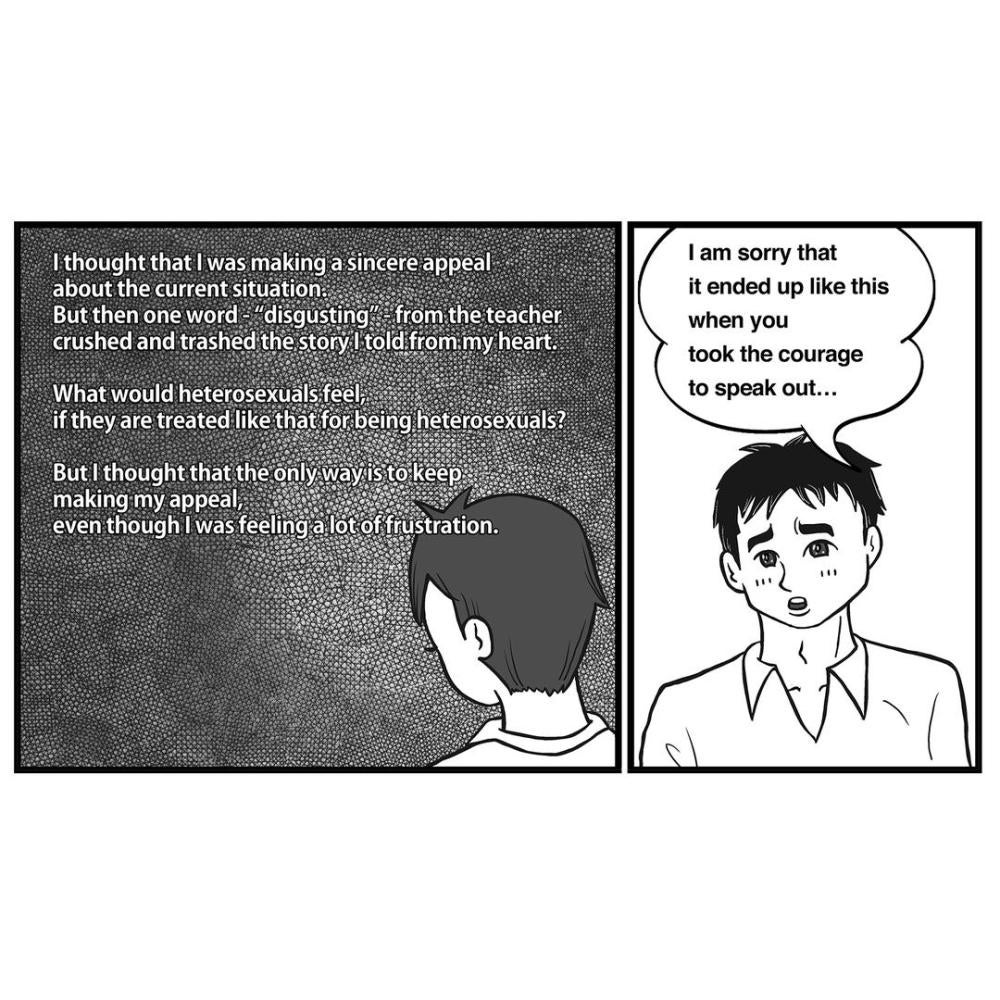

The struggle, they explained, was not coming to terms with being different as such, but rather searching for information about gender and sexuality amid a steady tide of stereotypes, misinformation, and noxious anti-LGBT rhetoric. In the rare cases when teachers or other school staff were supportive of LGBT students, the responses relied entirely on the initiative of individual staff members and not policies or protocols. Responses rarely featured recourse for incidents of violence or discrimination, or corrections of misinformation.

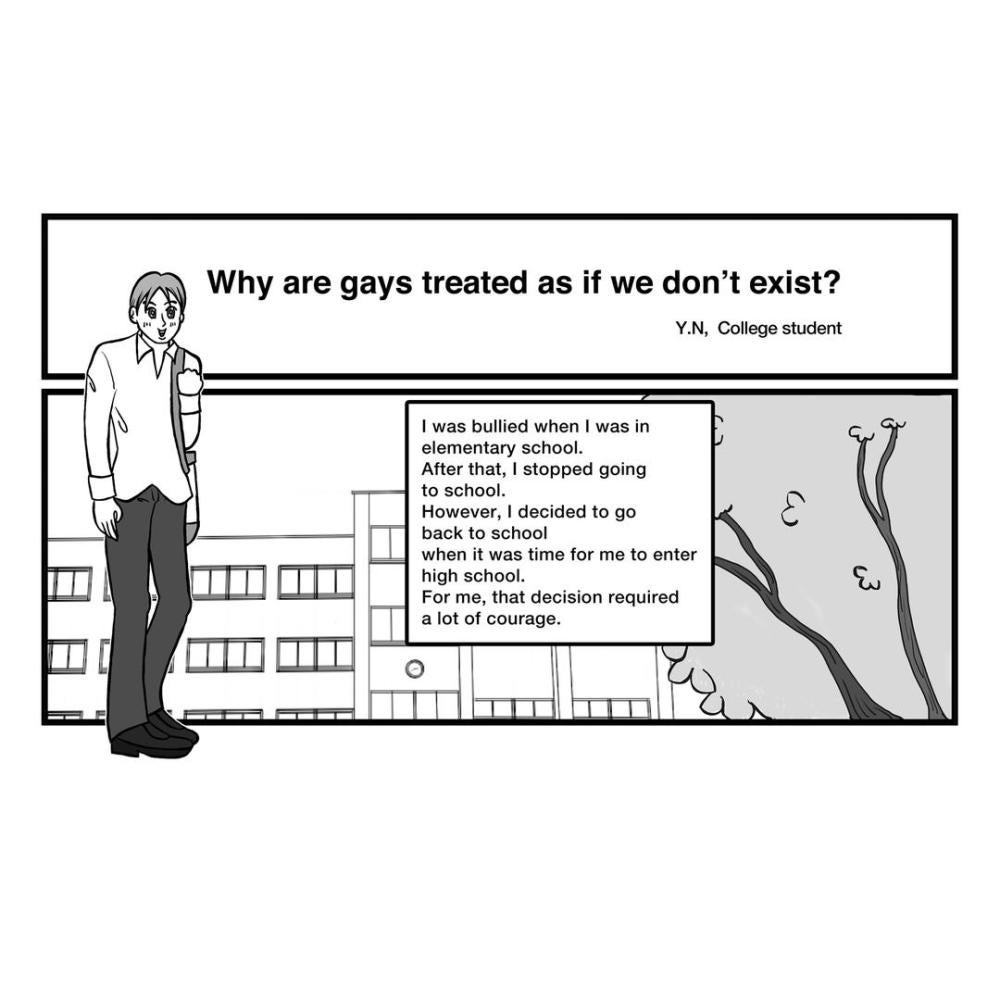

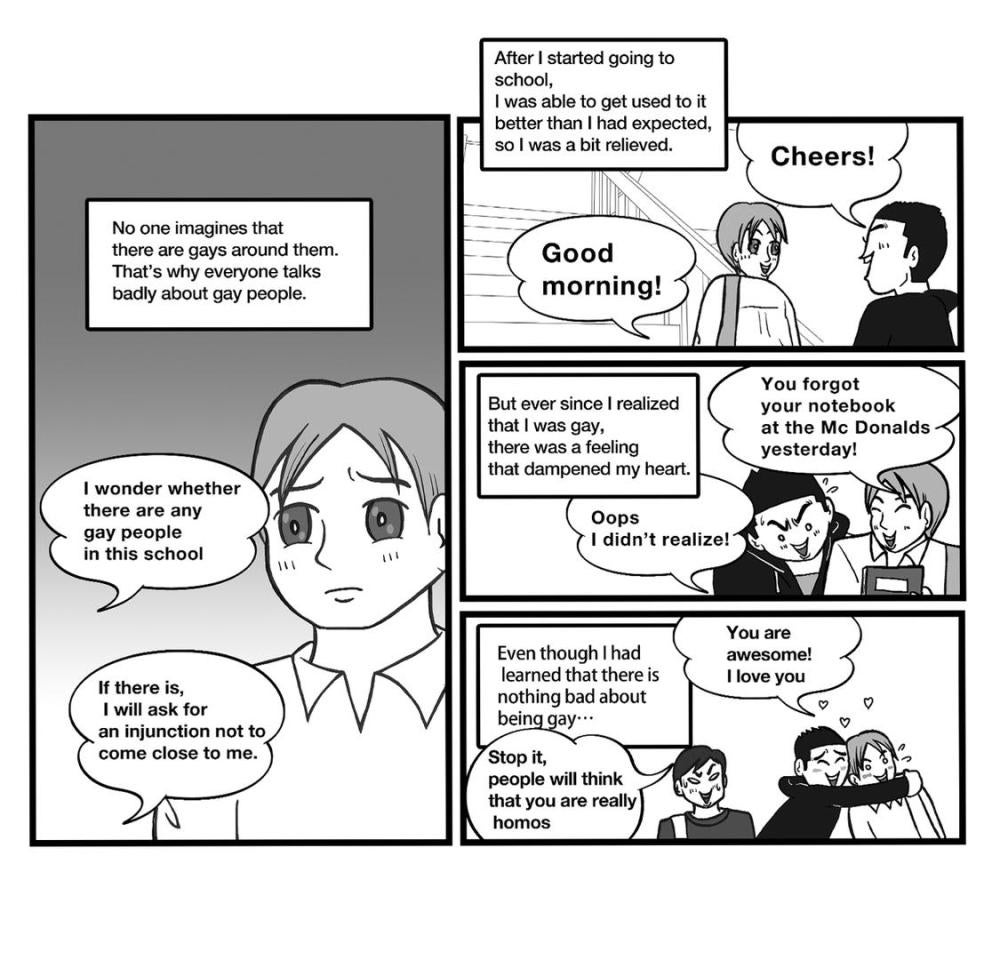

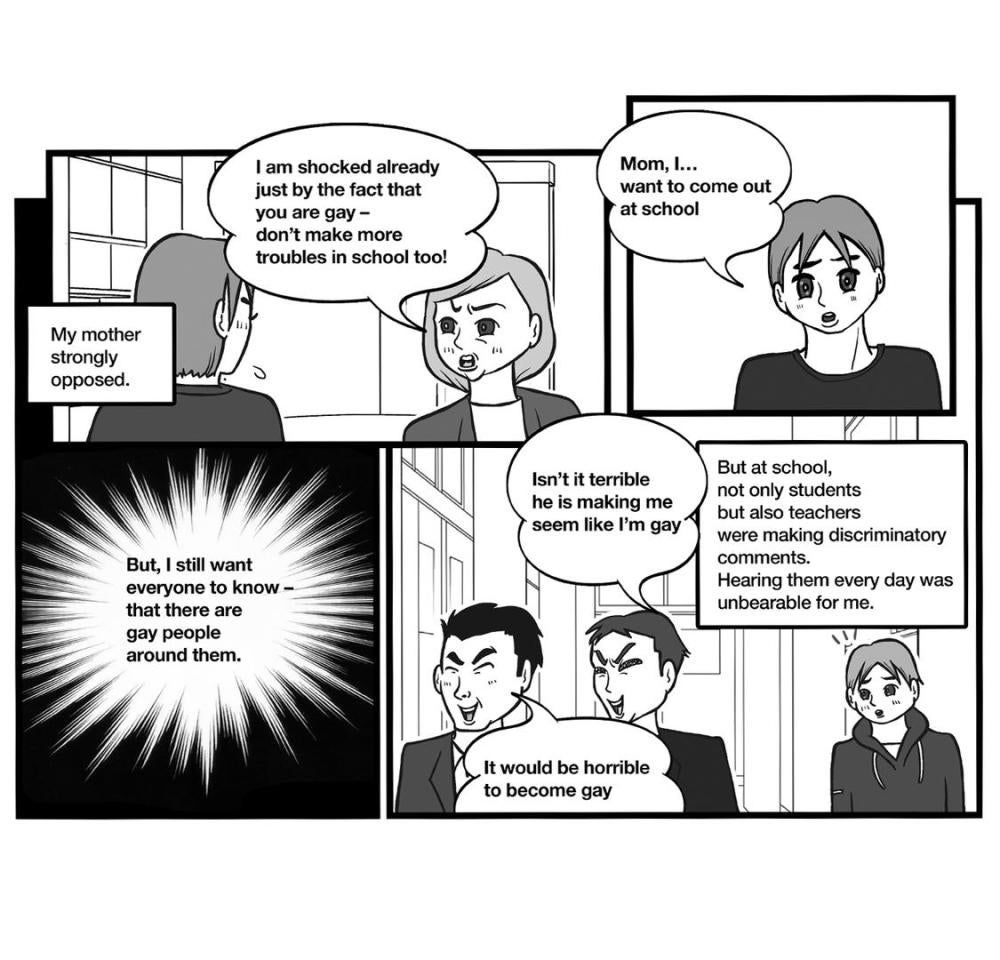

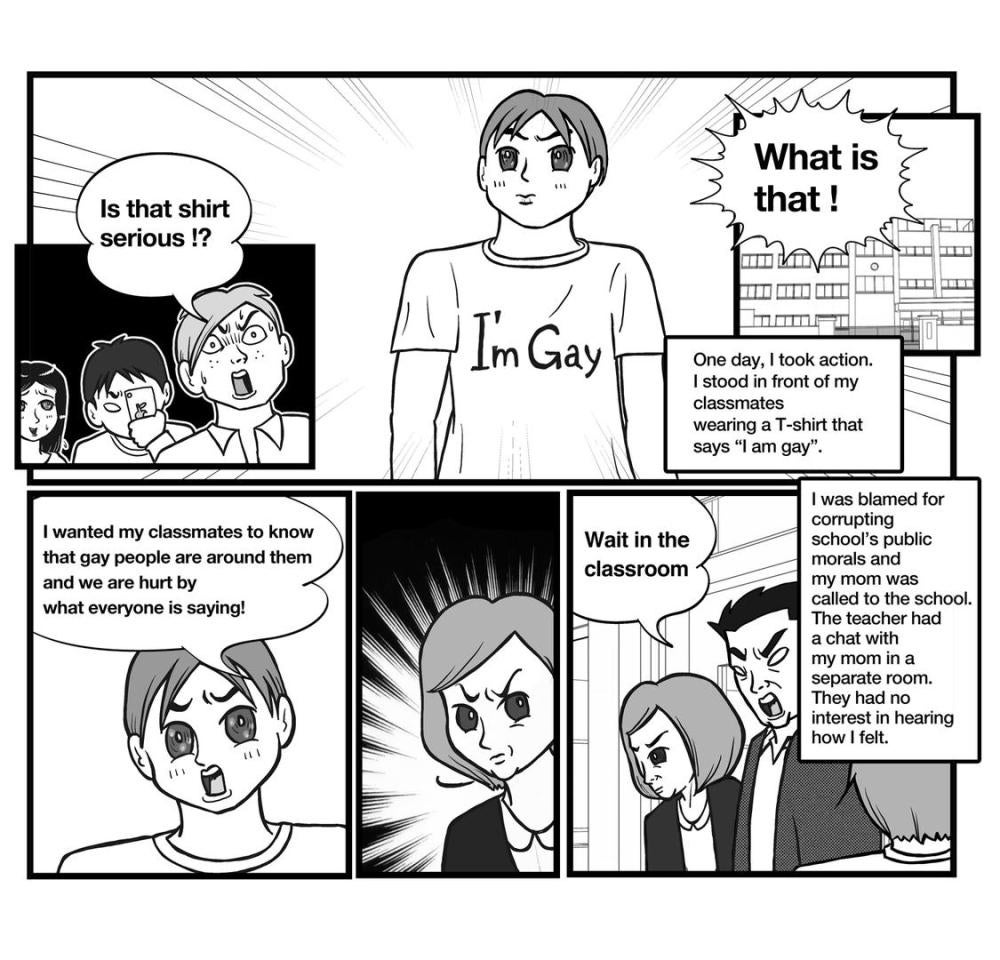

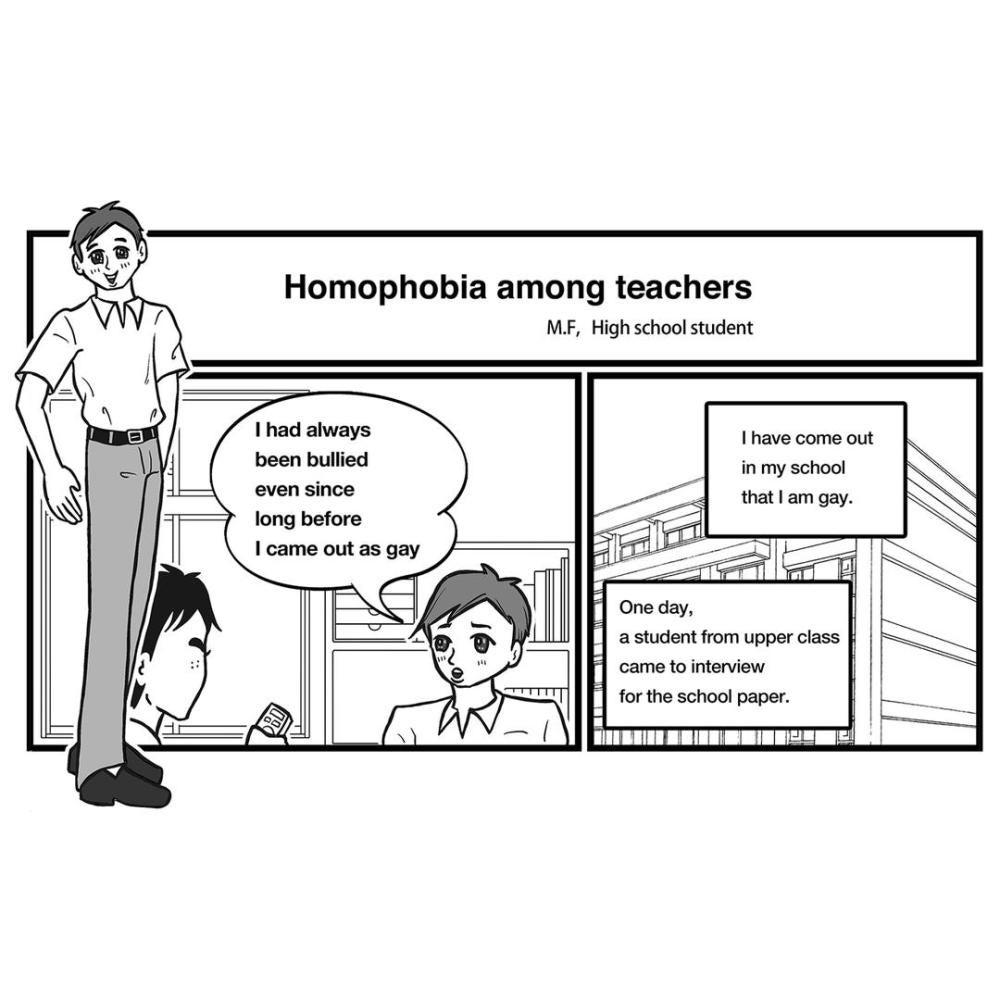

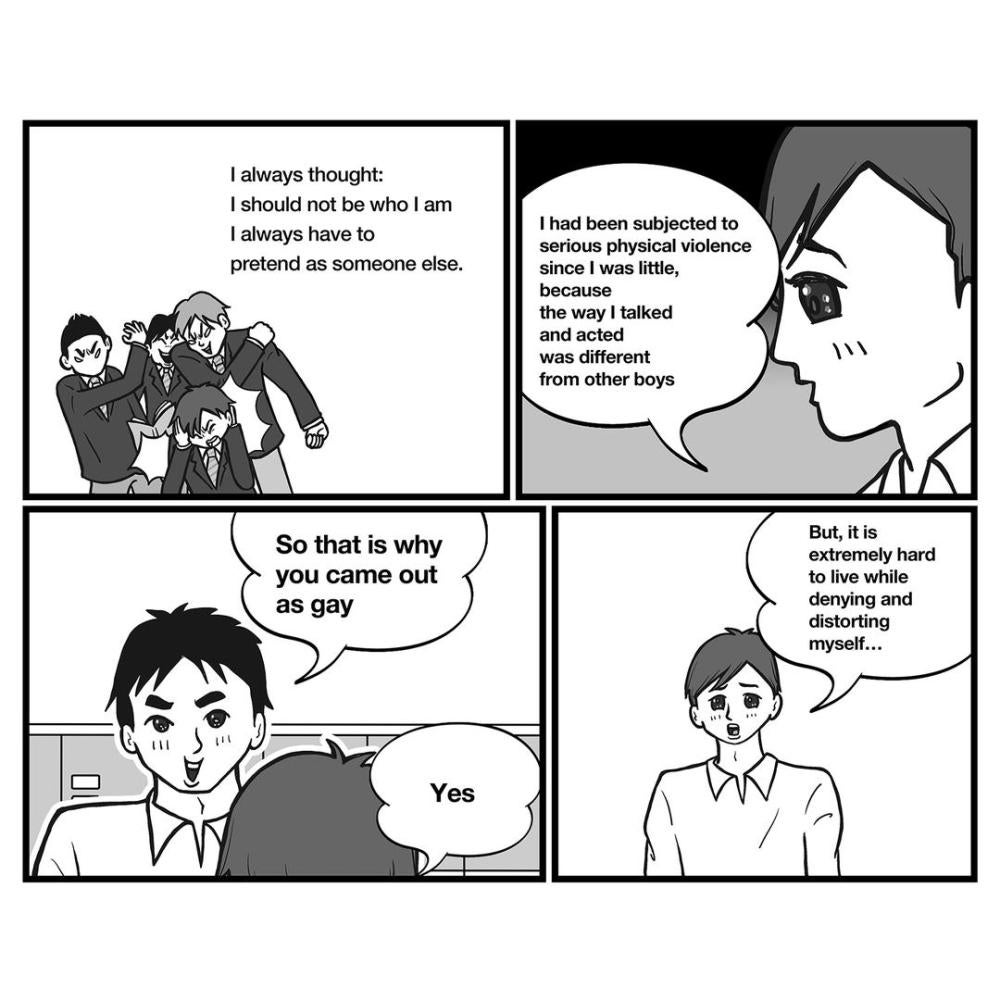

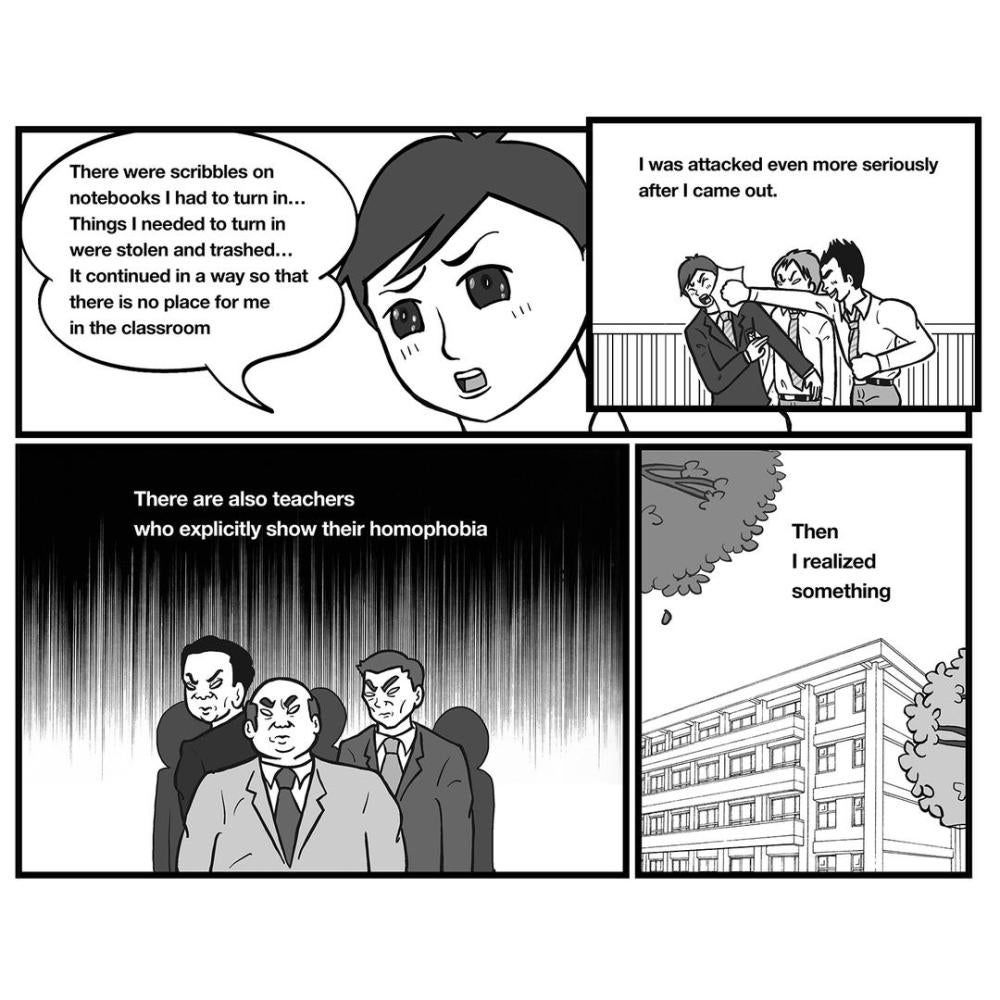

Osamu I., for example, came out as gay during high school only to face violence and harassment from his peers and ignorance and indifference from his teachers. Emboldened by learning about LGBT rights on the Internet and by other students at his school coming out to him in private, Osamu disclosed his sexual orientation during a school assembly by wearing a t-shirt that read, “I’m gay.”

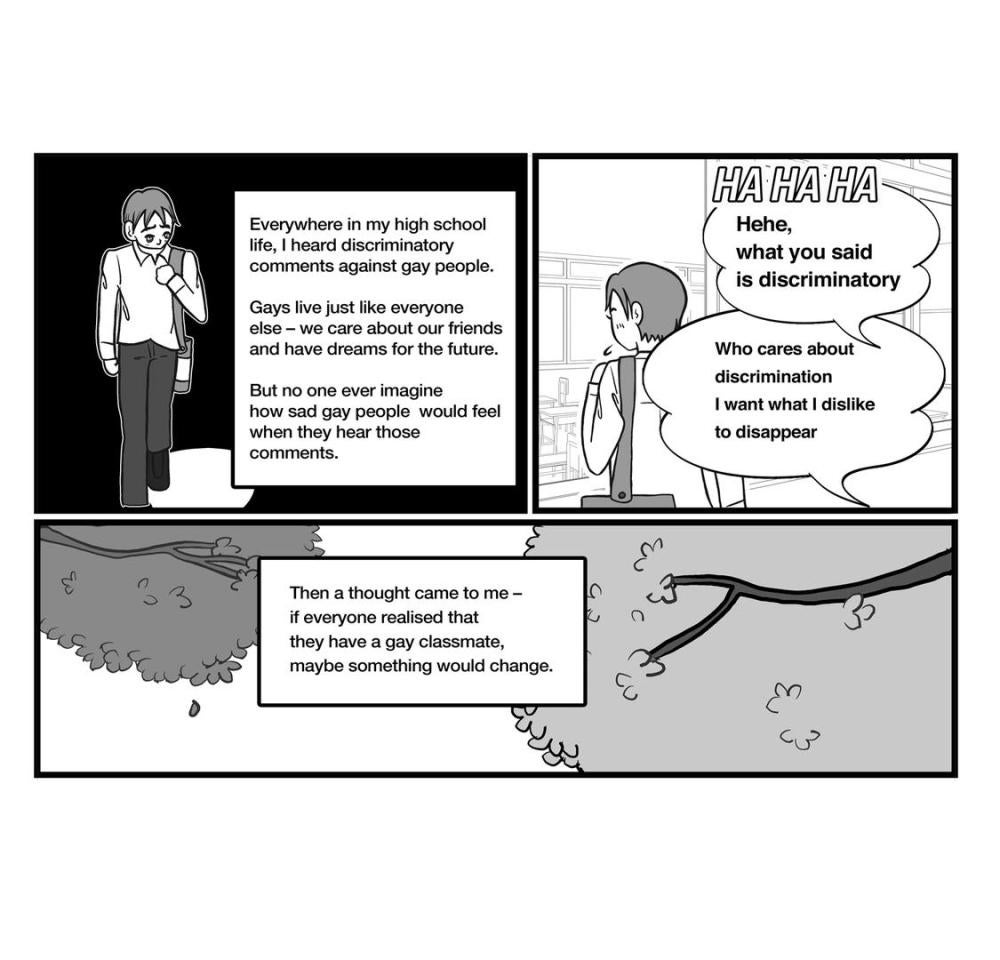

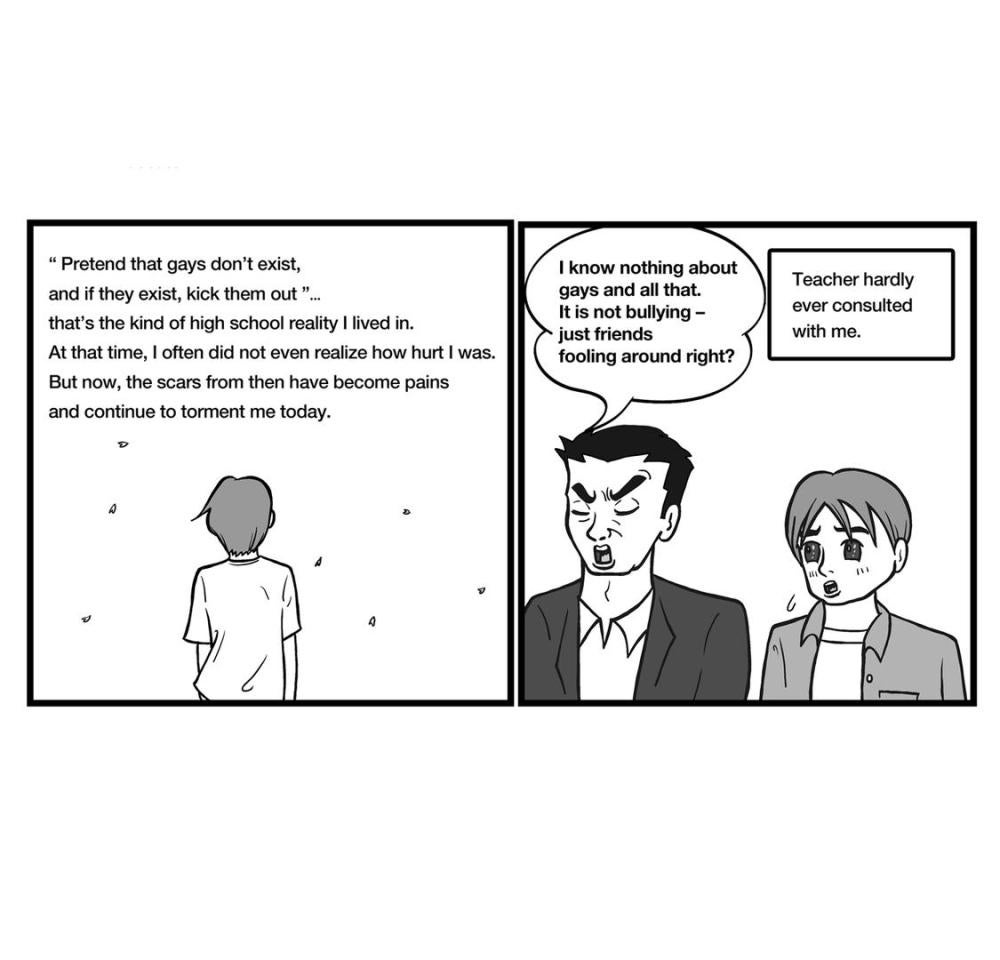

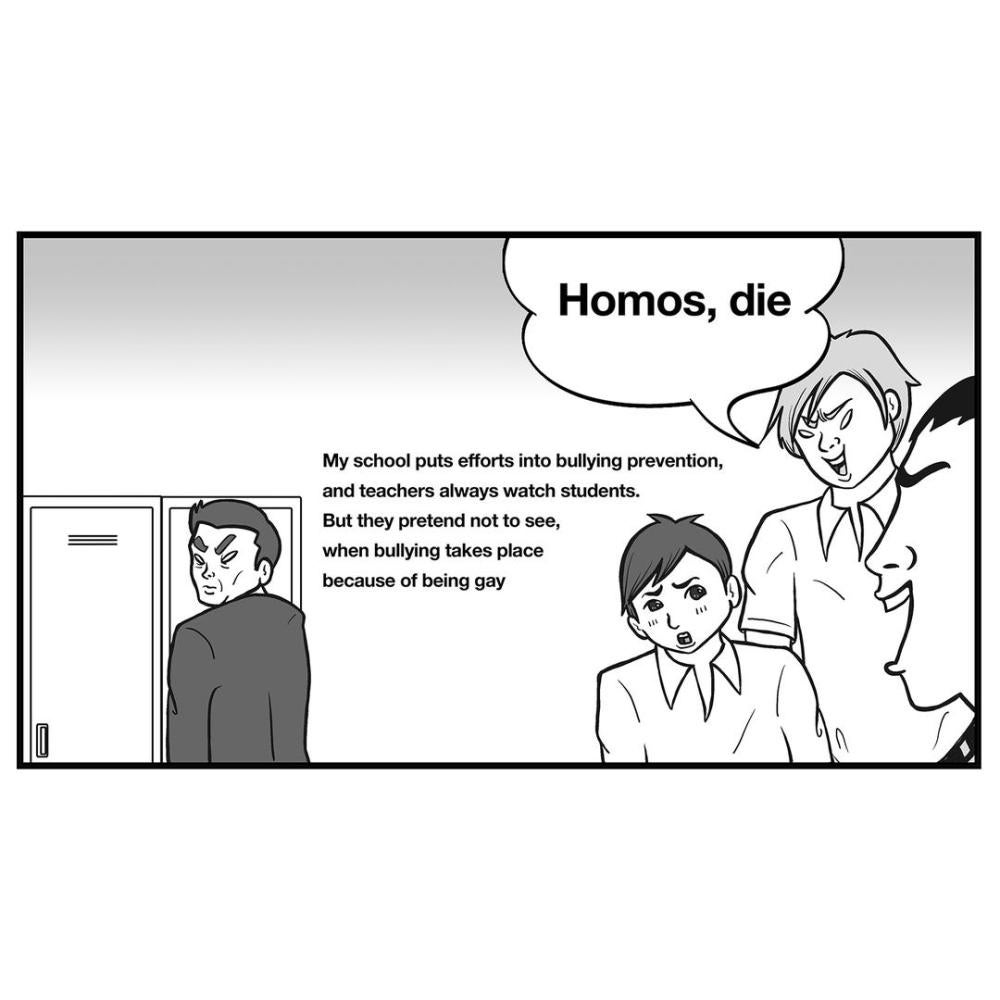

“I had heard a lot of gay jokes around me and I thought if the other students knew there were LGBT people around them, they might stop being so mean,” Osamu told Human Rights Watch. But his courageous pursuit was not met with support or compassion by his classmates or teachers. Without consulting him, school staff called his mother to complain about the incident. “The teachers told me that my coming out broke the harmony of the school,” he said.

That reprimand was just the beginning.

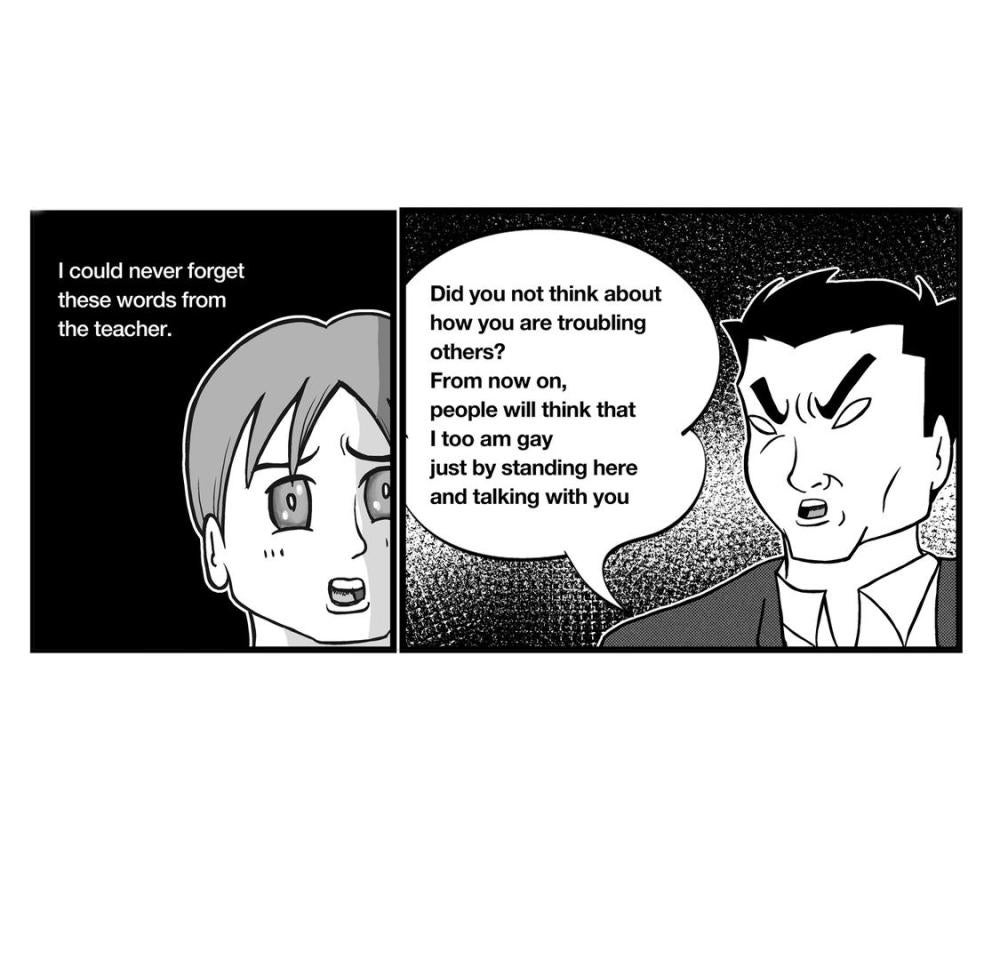

Osamu said that a few days after he came out publicly, his physical education teacher approached him and said, “I think other students think what you did was a joke but by even standing next to you, people will think I’m gay too.” His classmates teased him, saying he would have to use the girls’ changing room from then on. The teacher responded by instructing the class on the difference between sexual orientation and gender identity disorder.

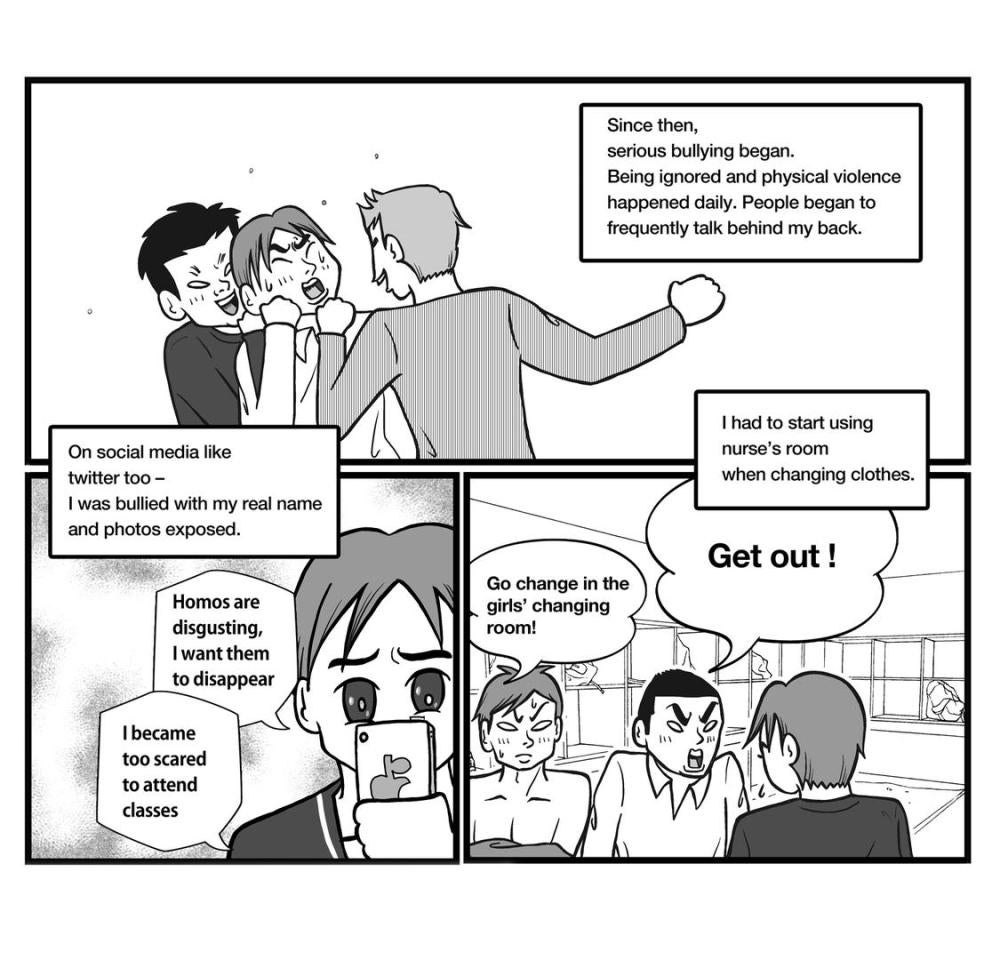

“That lecture only made it worse,” Osamu said, explaining that the teacher at no point mentioned kindness, tolerance, or human rights. At the same time, students began to circulate a photograph of Osamu wearing the “I’m gay” t-shirt on Twitter with hateful comments. During his next physical education class, a group of about 10 male students surrounded Osamu, kicked him, and threw balls at him.[2]

Within a few weeks, Osamu’s school had devised a plan to counter the bullying he faced. But the plan featured no investigation into the incidents, punishment for the perpetrators, or education on LGBT issues or bullying for the school body. Instead, Osamu was assigned to weekly meetings with a small group of teachers, and instructed to use the school nurse’s office to change his clothes for physical education class. “The PE teacher then

explained to me that this group of students that had attacked me thought we were friends and the kicking was a joke and meant as playful, not harmful,” Osamu said.

Ijime, or bullying, is common among all students in Japan, and LGBT students are among those who are specifically targeted by peers. Prof. Yasuharu Hidaka at Takarazuka University School of Nursing in Osaka, who has conducted surveys of gay and bisexual men and boys since 1999, found in a 2014 survey that nearly 44 percent of the 1,096 respondents between the ages of 11 and 19 had experienced bullying in school. In response to the bullying, 18 percent of overall respondents and 23 percent of teens avoided going to school. Self-harm, defined as cutting oneself with a sharp object, was reported by 10 percent of overall respondents and 18 percent of teens.[3]

LGBT Rights in Japan

While overt hostility toward LGBT people has been rare in Japan’s history and the constitution broadly bans discrimination, the lack of specific human rights protections on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity means LGBT people in Japan do not live on equal footing with others. Instead, life is characterized by invisibility. No national laws specifically mention protections or possible recourse for rights abuses based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Mass media portrayals of LGBT people have tended to rely on mockery or stereotypes.[4] According to OutRight Action International, “LGBT people are generally not portrayed by mass media or perceived by Japanese society-at-large as family members, friends, colleagues or neighbors.”[5]

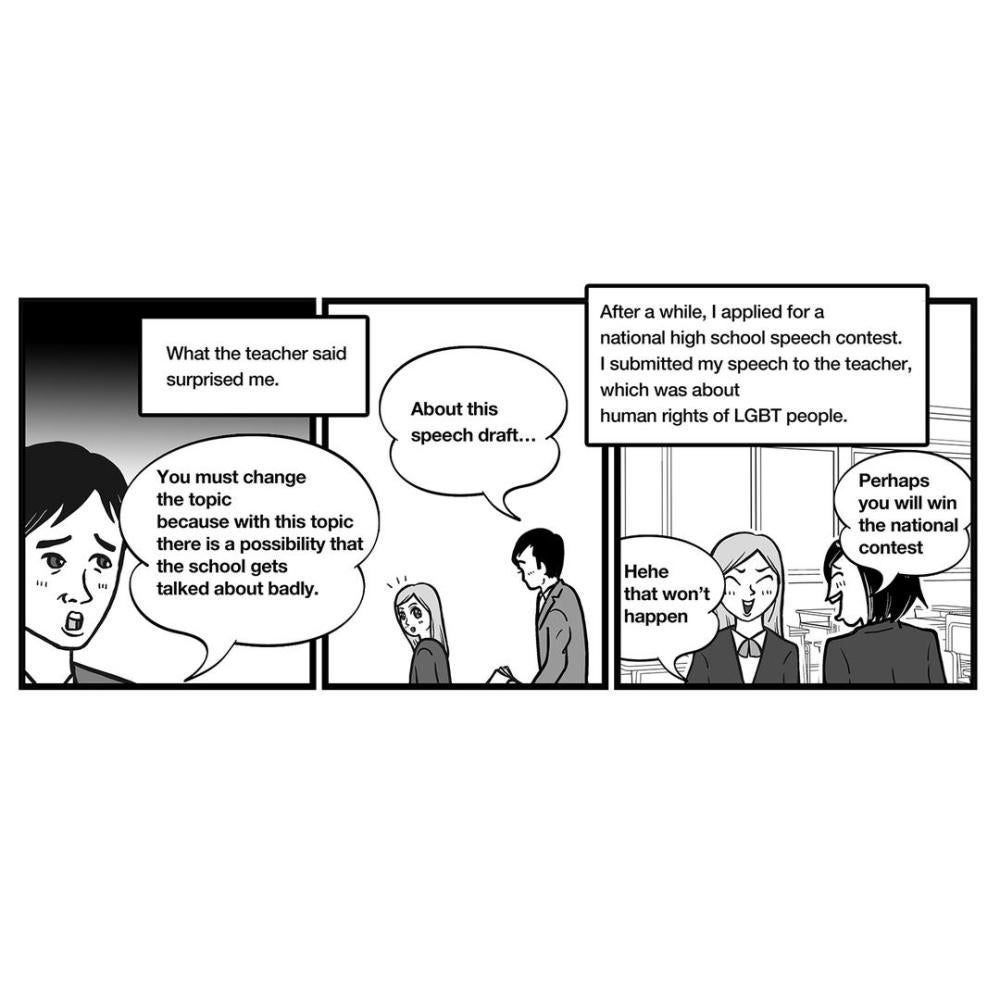

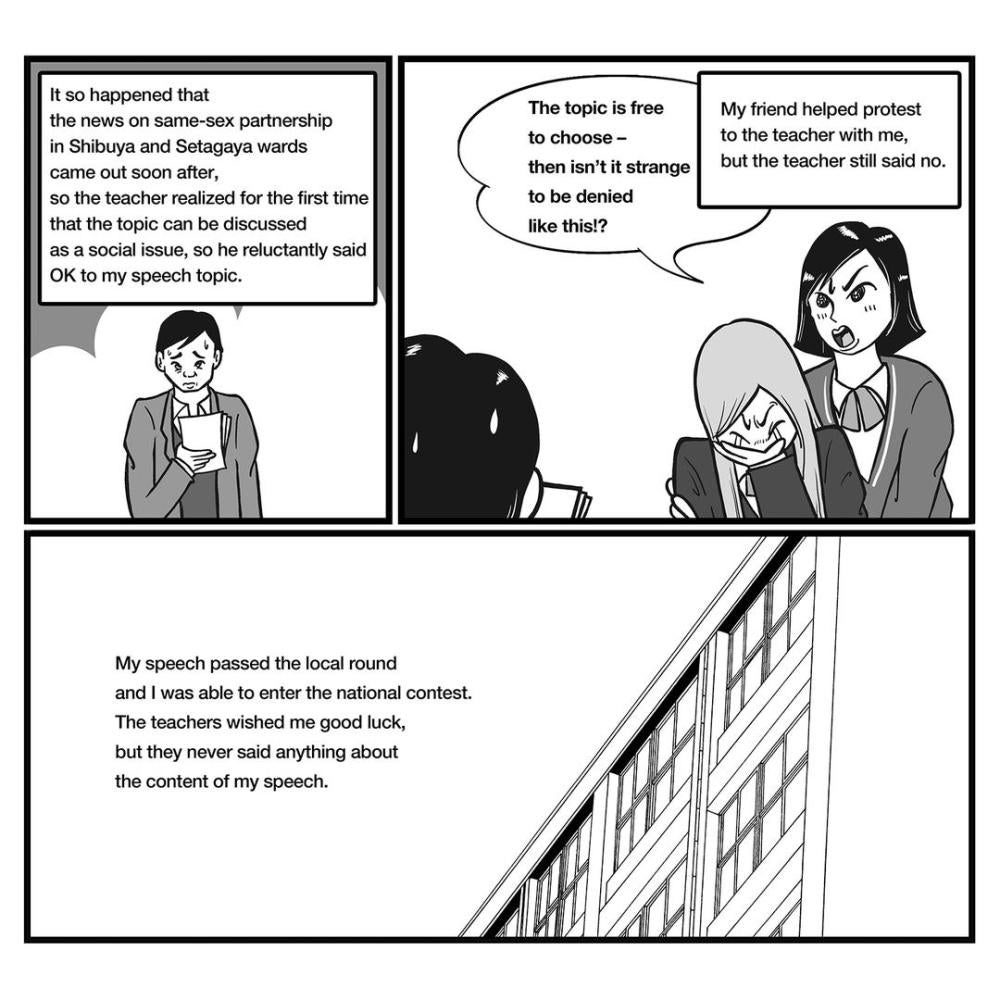

There has been growing focus of late on human rights issues that impact LGBT people in Japan, alongside increased public debate over gender and sexuality. Since 2013, two municipalities have declared themselves “LGBT friendly,” and two wards began recognizing same-sex marriages in 2015.[6] In recent years openly gay and transgender politicians have served in local legislative bodies.[7]

This momentum has resulted in some positive national policy shifts as well. For example, the 2012 revised version of the national suicide prevention policy specifically mentions LGBT people.[8] And in the wake of the 2011 earthquake that triggered displacement and trauma near the Fukushima nuclear power plant, the government allocated crisis relief resources specific to the LGBT community.[9] At time of writing, a multiparty caucus was considering comprehensive legislation on the rights of LGBT people. Proposals for the new law range from a comprehensive non-discrimination bill to a bill that just promotes understanding of LGBT people. It is currently unclear what the caucus will submit to the Diet, Japan’s parliament, and when it will do so. If enacted, such legislation would be Japan’s first comprehensive legislation on the rights of LGBT people.

There has also been progress in the area of education-related rights. In 2015, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) sent a directive to agencies including all school boards titled, “Regarding the Careful Response to Students with Gender Identity Disorder.”[10] The directive describes several accommodations schools should make regarding transgender students and mentions other sexual minority students as well. While the directive is non-binding, it sends a serious message from the ministry. In 2016, MEXT issued the “Guidebook for Teachers Regarding Careful Response to Students related to Gender Identity Disorder as well as Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity,” which signaled an evolving view on LGBT rights and recommended several protective measures for LGBT students, including:

- Clarification of the definitions of “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” and encouraging teachers not to confuse them;

- Acknowledgement of social prejudices against LGBT people in Japan and how they can result in workplace discrimination. In addition, the Guidebook states: “it is important that teachers stop having prejudices and gain a better understanding of this issue.”

- Following the 2015 MEXT directive discussed in the Disorder-Based Directive section of this report, the 2016 Guidebook clarified that schools should not compel transgender students to visit medical facilities [for the purpose of diagnosis?]. Suggesting that, with regard to transgender students’ health exams, which take place at the beginning of each school year, school staff can advise doctors to conduct examinations “on an individual basis”;

- Considering the possibility of sexual orientation and gender identity topics being included in human rights courses.[11]

While the 2015 directive opened up the important possibility of schools respecting students’ gender identity without a “GID” diagnosis, the document predicates gender identity on an outdated and discriminatory diagnostic model that sends a harmful message to students exploring their sexual orientation and gender identity. (See the Disorder-Based Directive section, below.) The 2016 Guidebook, while encouraging on many fronts, remains tied to the pathological model. In addition, both the 2015 directive and the 2016 Guidebook, while promising indications of the ministry’s commitment to working toward protecting the rights of LGBT students, are non-binding recommendations.

Overall, despite recent promising political dialogues, protecting the fundamental rights of all LGBT people in Japan—including children—remains an overdue obligation for the government.

Japan’s Bullying Epidemic

Increasingly universal, organized, persistent, vile, and disguised.

–Reference to bullying in a volume compiled by the Japanese Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry[12]

In February 1986, 13-year-old Shikagawa Hirofumi hanged himself in a railway station in Morioka, the capital of Iwate prefecture. For months, Hirofumi’s classmates had bullied him mercilessly—by heckling and beating him, marking his face with a pen, and damaging his property. His teachers were aware of the frequency and severity of the harassment and violence the boy faced. At a court hearing about whether the school could be held liable for his death, his homeroom teacher testified that he saw the treatment as “playful mischief,” not bullying.

Ignorance was not the only specious claim. A few months prior to Hirofumi’s death, some of his teachers had taken part in a mock funeral for him put on by the students bullying him. In Hirofumi’s final month alive, he attended school on only a handful of days.[13] In response to his death, the Ministry of Education for the first time called an emergency meeting to examine the issue of bullying.[14]

Hirofumi’s parents sued the local government in charge of the school in 1986; five years later the Tokyo District Court awarded compensation only for the mental damages caused by the bullying over which the school was negligent. However, the court did not admit the causal relationship between negligence of the school and the suicide, stating that, under the particular circumstances of Hirofumi, it was unrealistic to expect schools to foresee suicide as the result of bullying.[15] In 1994 the Tokyo High Court awarded much larger compensation for the mental damages for the bullying, however, the court still did not admit the causal relationship between the negligence of the school and the suicide.[16]

In the quarter century since that court case, the Japanese government has instituted several bullying-related reforms and guidelines, and has launched research initiatives and awareness campaigns. But the problem has not sufficiently abated. In 2014, MEXT recorded 188,057 bullying cases. That same year, only two students were suspended from school for bullying.[17]

Perhaps even more telling than the data is how similar the patterns of abuse are today to what they were decades ago in cases like Hirofumi’s—persistent verbal and physical abuse, groups ganging up on one student, and teachers acting as bystanders and sometimes participants in the incidents.

The Japanese government has failed to significantly investigate the causes of bullying or institute policy reforms that address these foundational issues. That is, while the government has dedicated resources and political capital toward addressing bullying in schools, it has failed to analyze or enumerate in policy the causes of bullying or related specific vulnerabilities of some groups of students.

In doing so, the government has ignored international best practices to prevent and end bullying, and has failed to adequately uphold its commitments to children’s rights to education, access to information, and freedom of expression.

Japan’s school bullying problem has been linked to national political trends, cultural influences, and economic and demographic fears. Anthropologist Anne Allison in her book on Japan’s contemporary socioeconomic insecurity argues that bullying, as well as school staff and parental responses to it, indicates the intense pressure on young people to conform and perform. She states:

The parent who refuses to pamper their bullied child, thereby forcing them to become tough as nails, is something of a Japanese ideal. In this narrative, children are inspired to not only stay in the world but to kick ass—Japan as number one.

Drawing on her decades of research, Allison calls school bullying “notoriously brutal in Japan,” and notes that while a minority of students seek their parents’ help in cases of bullying, some “young Japanese who are bullied at school and withdraw into self-destructive behavior find exit strategies with the imaginative help of their parents.” Allison documents one case in which parents, having allowed their daughter to stay home from school to avoid bullying, ask a teacher who is concerned about the child’s absences whether the school can provide protection for her return, and are told it is not possible.[18] Other scholars observe that, historically, “Cases of ijime were viewed as a sign of failed homeroom management. As a result, many homeroom teachers are reluctant to ask for help from other teachers, administrators, or counseling professionals.”[19]

Shoko Yoneyama, an education professor who researches bullying in Japan, contends that schools “have become dysfunctional communities unable to deal with bullying.”[20] Accordingly, widespread “tacit approval from bystanders adds legitimacy, and a feeling of normalcy, to the bullying,” meaning “students in such a dysfunctional community shudder with fear at the thought of sticking out in the group.”[21] In the school environments Yoneyama and other scholars have researched, “Students are bullied after being labelled as selfish, egotistical, [or] troublesome to others because of slowness in doing things, [being] forgetful about bringing things to school, not following rules, [being] unclean, [or] having unusual habits.”

The normalcy of bullying is reinforced when teachers take part in the abuses, which, Yoneyama observes, can happen when a teacher “uses the bullying as a method of classroom management by siding with this powerful group of students.” In a school system that has been critiqued for aggressively promoting conformity, researchers have observed that social control in junior high school and high school settings can be meted out via peer pressure—including bullying.[22] As Yoneyama states, “Although students themselves may not be aware of it, bullying serves as an illegitimate, ‘school-floor’ peer-surveillance system, which helps to perfect the enforcement of school rules.”[23]

Other researchers on Japanese youth have called bullying “a distinctive and brutally effective means of behavior modification,” noting that “clinical therapists collect enormous files of data recording Japan’s most notorious bullying incidents.” But while “newspapers regularly report on some of the most egregious [bullying] cases, the vast majority are so common that they don’t warrant public attention.”[24]

“Every patient I have ever seen in my clinic has experienced bullying at some point at school,” said Dr. Jun Koh, a psychiatrist in Osaka who has counseled nearly 2,000 gender nonconforming children. Some have stones thrown at them, he explained, however, “When bullying starts, before things escalate to physical violence, most kids stop going to school because they are already experiencing so much anxiety and fear in the face of the verbal abuse alone.”[25] In a volume compiled by the Japanese Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, one scholar states: “Bullying has become increasingly universal, organized, persistent, vile, and disguised.”[26]

Yet while the problem of bullying has received scholarly and media attention, the government has not enacted adequate policy changes to address the issue. This is partly due to broader claims by the government about the state of the nation’s social fabric and education system. For example, in 1998 MEXT issued an education reform program that linked bullying to an erosion of community-based education:

While life [for children] has become affluent and education has quantitatively expanded, the education influence of the home and local community has declined, excessive examination competition has emerged as educational aspirations have risen, and the problems of bullying, school refusal, and juvenile crime have become extremely serious.[27]

An education expert who sits on the national curriculum reform committee told Human Rights Watch there was no need to discuss different types of children and their experiences of bullying because all bullying happens for the same reason—that certain children are different and stand out—and can be solved through one method, a tribunal run by peers.[28]

A senior researcher with MEXT’s National Institute for Education Policy Research expressed similar views, telling Human Rights Watch:

One thing that I want to be very clear on is that I’ve never myself heard of a student specifically being bullied for being gay or lesbian.… Whenever a student is asked, “Why did you do this to other students?” the student will almost always say that the one who is bullied is not like everybody else. I feel that this is just an excuse. It doesn’t hold true.

There’s a lot of talk about how to make students less of a target, but that’s not the real issue. If someone becomes a target, that has nothing to do with them; rather, it’s the bullies who are frustrated, under stress. Changing the mindset of people who might bully someone else is the real solution. That’s what needs to be looked at.[29]

But researchers and other experts described bullying and harassment of LGBT students in terms which differed from the official line that any student could be bullied at any time. Keiko Suichi, who leads the Japanese Federation of Bar Associations’ work on bullying, said, “Being LGBT, or being seen as LGBT, definitely could be a basis for bullies to target students.”[30] Asked if LGBT students were any worse off compared to other students with regard to being targeted for bullying, Prof. Yasuharu Hidaka said:

LGBT students are worse off. They face more difficulties. I have no precise data on how much worse off they are, but boys especially report experiencing bullying that is more of a sexual nature—having their pants taken off in front of others, for example. Moreover, when LGBT youth experience bullying, they find it difficult to ask for help, because if they want help, they would have to disclose their sexual orientation or gender identity.[31]

The incidents of bullying and harassment of LGBT students presented in this report demonstrate that there are students in Japanese schools who, due to policy gaps, inadequate teacher training, and weak enforcement mechanisms, are targeted by bullies because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.

Compounding the restrictions that limit their freedom of expression, LGBT students in Japan attend classes where they are not systematically included in the curriculum. This gap in information leaves students seeking information in a lurch, and teachers charged with imparting knowledge and supporting student growth without fundamental facts to share.

Information Vacuum

Sexual and gender minority children told Human Rights Watch about their quests for information at their school libraries, online, and in rare cases, by asking adults around them about sexual orientation and gender identity.

In some cases, children said they encountered small pieces of information in official sources, such as textbooks, leading them to assume it was acceptable to inquire further about the topics. However, those who pursued inquiries with school staff often received ignorant or prejudiced responses from teachers that caused students to think of their identities as pathological or problematic.

As Prof. Yasuharu Hidaka has found in his regular surveys of gay and bisexual men and boys:

[Many]have no proper information from society about sexual orientation and gender identity. Usually the information they do get is rather negative, that being a sexual minority is abnormal. Or maybe they get no information at all. We’ve seen this trend for a long time. But very recently, with the younger generations, fewer people have answered that they learned nothing about sexual orientation and gender identity. But the negative information they’re getting has increased.[32]

Students described how this environment affected their ability to learn about and express themselves. For example, 14-year-old Rei N. in Okayama, who identifies as x-gender[33] said:

It would make an enormous difference to include LGBT issues in the curriculum. In my health textbook there is one reference to homosexuality, but only that it increases risk for HIV.[34]

Another interviewee recalled how in health class the teacher had introduced the textbook’s sole passage about same-sex relations by teaching the word “homo,” which is often used as a slur, and remarking, “I have never heard of these people in reality.”[35]

Such behavior from teachers left students in a vulnerable position. As Akemi N., an 18-year-old transgender male bisexual in Okinawa said, “If the teacher had had any knowledge, I could have gained positive knowledge about myself instead of so many questions all of the time.”[36] Instead, he said he learned about gender and sexuality mostly through comics he could find in local stores—an increasingly common medium where LGBT issues are discussed openly.[37] A researcher studying the use of manga cartoons in lieu of comprehensive sex education observed that while “teen manga and magazines have taken up the slack and provide young people with a wide range of information about sex … those informal sources of sex education prove confusing rather than instructive.”[38]

LGBT teachers told Human Rights Watch that they did not feel that they could come out at school—not because they worried that they would lose their jobs, but because they feared that they would lose the respect of their students and peers.[39] As a result, LGBT students frequently have no adult role models whom they know to be LGBT, increasing their sense of isolation.

In addition to failing to provide children with accurate and objective information about gender and sexuality, the information gap can also impact teachers, who are not uniformly required to learn about either the issues impacting LGBT people or the very concepts of sexual orientation and gender identity. This can mean that even well-intentioned teachers who attempt to support LGBT students end up making preventable mistakes, which only further engenders distrust between students and the adult staff at their schools.

A counselor at an LGBT youth organization in Fukuoka that provides direct services to students as well as outreach to schools explained that most teachers he has encountered think students who are gender nonconforming are “being selfish.” The counselor said:

This is what they tell the kids and this is what the kids come asking us about. It is so damaging when a kid is struggling already with these feelings, then they are told by a teacher that they are arrogant, then by a psychiatrist that they have a disorder.[40]

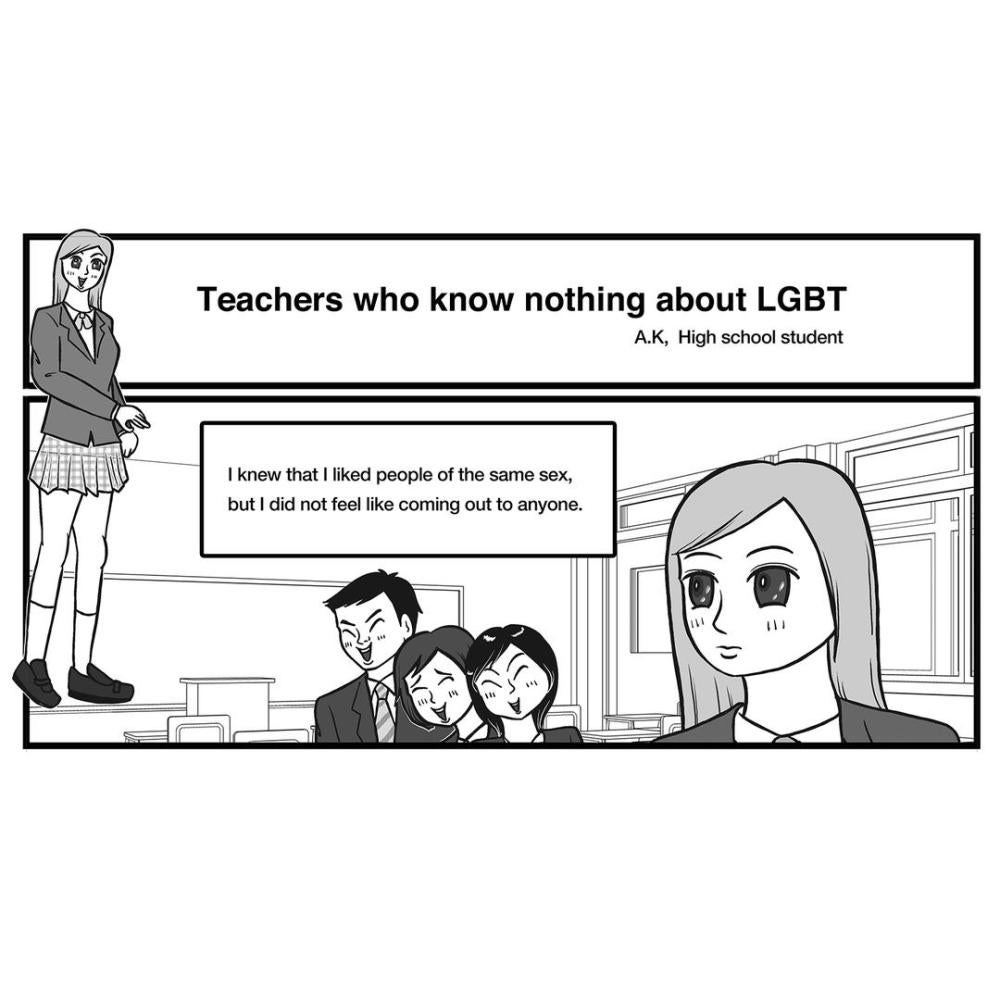

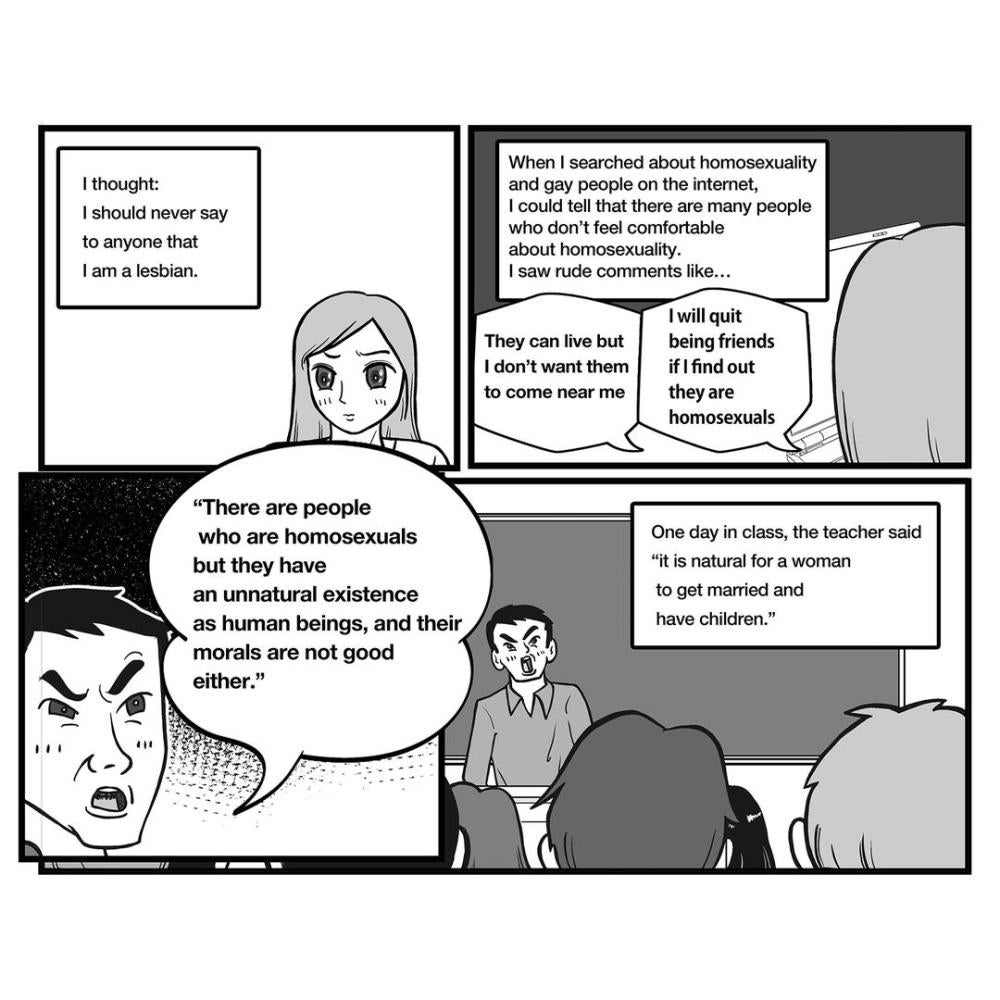

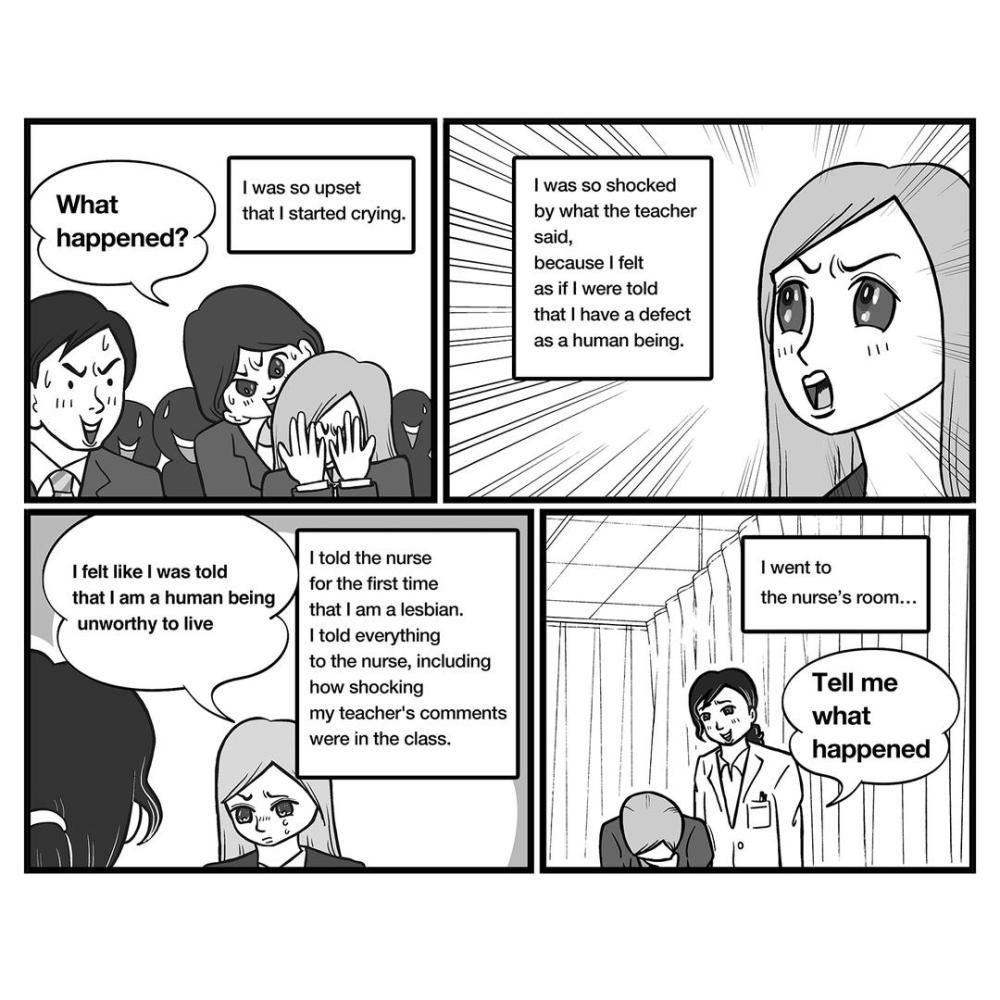

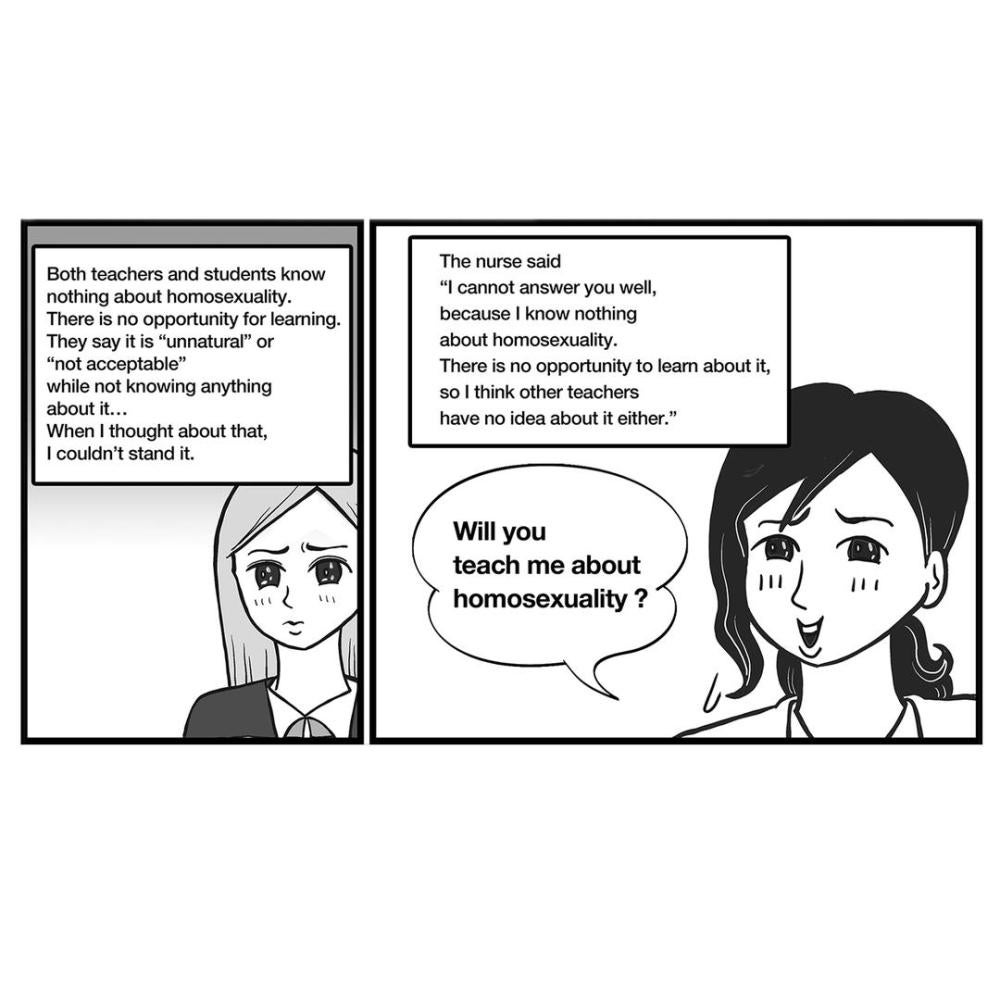

Even when the prejudiced attitudes are subtler, they can have a drastic impact on children. For example, Naoko Y., an 18-year-old lesbian in Nagoya, told Human Rights Watch that while she knew of her sexual orientation early in her life, she kept it concealed, which required an enormous amount of energy and careful effort. Then, during a home economics class in high school when she was 16, the teacher instructed all of the female students that their responsibility in life was to get married to a man and have children. Naoko said, “I got really upset during the lesson and I started to panic. I couldn’t breathe. I started crying.” The home economics teacher sent her to the student health center, where she proceeded to tell the nurse that she was a lesbian. “The nurse was very surprised,” Naoko said. “She told me, ‘I don’t know anything about this so please teach me.’”[41]

Even though the school nurse’s ignorance added to her burden, Naoko later saw the episode as a lifeline. “I visited the health center nurse every day for a year,” she told Human Rights Watch. “It made me feel much better to know one adult who could support me.”

A 19-year-old transgender woman in Setagaya stressed the need for safe spaces in schools. She recounted that when she told the high school nurse about her gender identity, the nurse’s response of “don’t feel bad, it’s not strange, and you’re not alone,” prompted her to return regularly to meet with the nurse so that she could feel safe at school—including a visit a year later when she asked for help finding information about LGBT people because there was none in her school materials.[42]

A university student in Tokyo who went to secondary school in Niigata prefecture told Human Rights Watch that the lack of information or safe spaces for meeting other LGBT people led him to try to enter gay bars during his high school years. He said that over time the Internet improved his access to gay information and networks, but, “What I really want is for LGBT issues to be taken up in classrooms.”[43]

A counselor at an LGBT community organization in Osaka said that many LGBT youth who visit their drop-in center or call their hotline say that often interactions with school staff intimidate them into distrusting their teachers. “Sometimes students tell us they are afraid to come out at school … because then they face a lot of pressure to stand up in front of classmates and explain LGBT issues,” she said. She described a 2014 case in which a university student came out to his professor, who then requested that the student give a presentation on LGBT issues to all students. The student committed suicide, which she believed was due to the pressure: “It’s a lot of exposure very quickly, especially for young people.”[44]

Kenji D., a transgender student, said that when he was 15 he told the school nurse and a group of his teachers that he did not feel like a girl and had questions about where these feelings came from. “They responded to me that it’s a temporary thing and that I would grow out of it,” he said, adding that the response made him deeply sad because he had “so much respect for the teachers but they knew nothing about [him].”[45] Other interviewees said teachers reacted to their disclosure by explaining how being LGBT would impact their ability to “do normal things” or participate in school activities on equal footing with other students.[46]

Saburo N., a counselor who works in three public schools in the Tokyo area, said that the root of the poor response from teachers can be found in the lack of consistent training: “There is no mandate to understand LGBT people so the teachers don’t act. It’s their ignorance but it’s harming the children.… There’s no foundation for understanding … because it’s not in the curriculum.”[47]

A counselor who worked as a teacher for three years said that even well-intentioned teachers are handicapped by the lack of training: “Teachers just have no idea about the issues, or how to respond to them—let alone how to prevent them.”[48]

Lack of knowledge does not always prevent care for children. Takeshi O., a 19-year-old transgender man in Tokyo, said that when he approached a junior high school teacher for help with changing his school uniform and making other accommodations according to his gender identity, he felt safe “because [he] had already established a relationship with her and she liked [him].” The teacher met with other school officials and formed a committee to address attire, restroom use, and extracurricular activities, all issues related to gender segregation. However, the teachers also made clear to Takeshi their motivations. “The teachers weren’t knowledgeable of LGBT issues but they knew me and said they were trying to figure out how to help me as a student they knew—and not to take this up as an LGBT issue,” he said.[49]

A curriculum that neglects inclusion of information about sexual orientation and gender identity fails students. Ad hoc or optional training programs for teacher sensitivity are not an adequate response. Researchers studying classroom management in Japanese junior high schools reported that teachers found “proclamations about the need to adopt more

‘friendly’ approaches to student guidance were difficult to translate into concrete action. The absence of a detailed set of procedures … left many instructors feeling unmoored.”[50]

“The Ministry of Education needs to mandate knowledge,” a high school teacher in a Tokyo suburb told Human Rights Watch. “I only read a booklet about LGBT people because I knew Human Rights Watch was coming to interview me. I don’t know anything professionally, everything I know about LGBT people I know from my personal life and a handful of gay friends.”[51] In place of formal science and rights-based teacher training and classroom instruction about sexual orientation and gender identity or expression, students in Japanese schools are often left to absorb information, sometimes even their initial exposure to information about themselves, from homophobic rhetoric and bullying.

Verbal Harassment

Mitsuru Taki, a senior researcher with the National Institute for Education Policy Research, explained that typical forms of ijime, or verbal harassment, consist of:

Excluding someone from the social circle, ignoring someone when the person speaks, [and] talking badly about a person behind his or her back. In addition, more direct forms of harassment include name-calling, threatening someone, physical violence in some cases, and stealing or hiding things.[52]

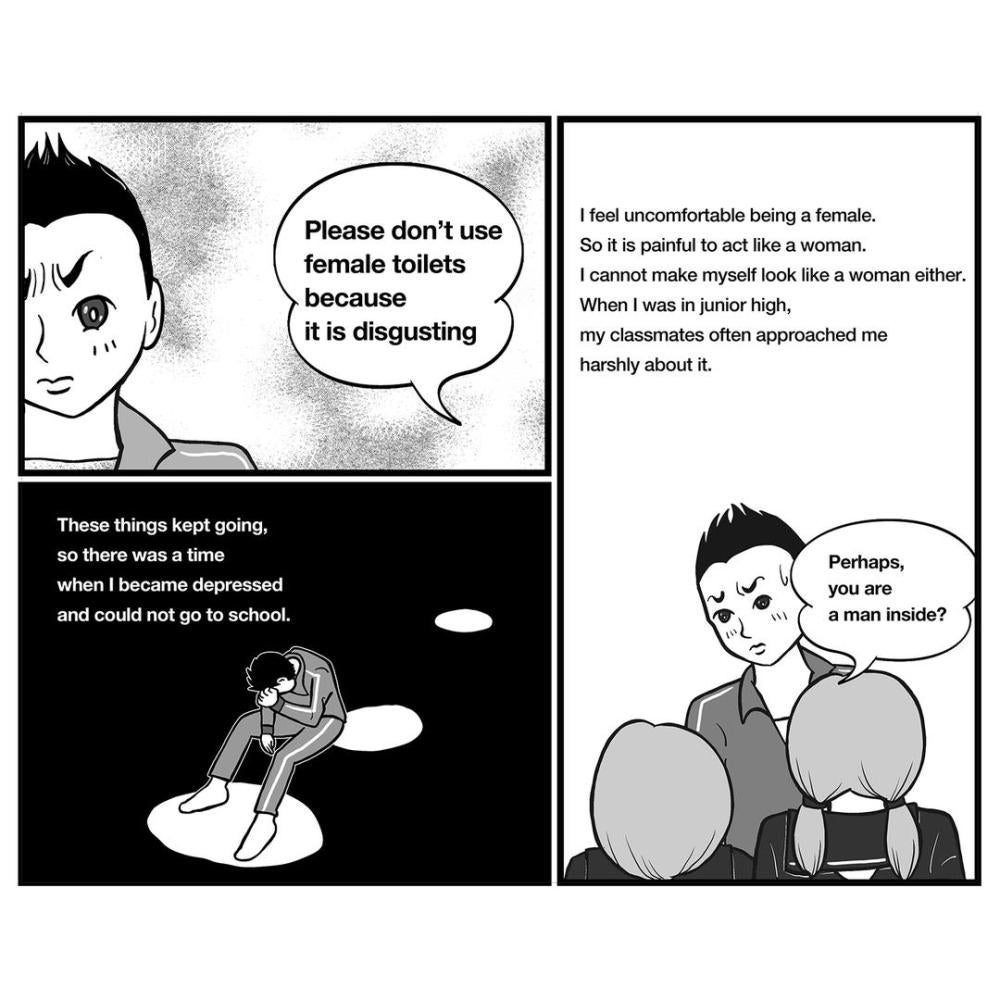

Nearly everyone Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report said that they heard anti-LGBT rhetoric in school, including LGBT people called “disgusting,” the use of slur words such as “homo,” and declarations that “these creatures should never have been born.”[53] For some, the words were directly targeted at them. For others, the insults stung as peers hurled them at each other, even if the deployment was generic and not because the targets were actually gay. And for those that witnessed teachers observing and participating in the hateful verbal attacks, their perception was cemented that school was an unsafe environment where conformity and harmony were privileged over dignity, security, and free expression.

Survey Questions Data Graphic[54]

“In school, gays were one of the good topics for bullying people,” said Daichi L., a gay man in Tokyo, recounting how a friend of his was frequently called gay by other students even though he was not. “Any boy who acted a little less masculine—people would say ‘gays are so disgusting, you are so disgusting.’”[55] Others pointed out how anti-LGBT insults were used as common slurs in jokes, and ascribed the lack of teacher response in such instances to a widespread understanding that this was a playful way for students to interact.[56] A teacher at a Tokyo high school who told Human Rights Watch that schools should never cover issues of sexuality explained that he heard anti-gay insults “fairly often,” but that “sometimes students use ‘homo’ but it doesn’t really mean gay. They are just using it to make fun of people in general.”[57]

Teachers can be part of the problem both by not addressing anti-LGBT rhetoric and also by participating in it. Interviewees described teachers using “homo” or other gay slurs as common jokes or insults.[58] Akemi N. said that because his teachers never taught about LGBT topics formally, he “only heard about LGBT people from teachers when they made gay jokes.”[59] Tadashi I., a 17-year-old gay student in Nagoya, said he was teased by teachers because he was shy and drawn to spending time with his male English teacher instead of his peers. “One day a teacher standing in a group of other teachers asked me if I like that English teacher so much, why didn’t I give him a romantic gift like chocolates, then they all laughed and used the word ‘homo,’” he said.[60]

Naoko Y. said she has heard homophobic slurs throughout her time in elementary, junior high, and high school: “The situation for me hasn’t changed since elementary school. So many homophobic remarks all the time. So I don’t know what to compare it to, I don’t know what a safe school is like.” For Naoko, the anti-LGBT remarks from teachers began in junior high school when multiple teachers would bring up gay people and denounce them as disgusting or bad. “When I heard a teacher say this, I took it as true—meaning I thought everyone believed that everywhere, so I needed to be completely quiet about how I felt,” she said. “The teachers’ opinions were very powerful over me.”[61]

Tamiko A., a 19-year-old lesbian in Okinawa, said abusive reactions from teachers dated back to elementary school:

During the last year of elementary school, two male students were holding hands [and] other students called them “homo.” The teachers laughed at the incident immediately—there was no chance to try to address this bullying because the teachers were laughing along with the other students from the moment it started.[62]

Another interviewee recalled an incident in junior high school:

When I was 14, one classmate said to our male teacher that “this student is a homo,” and pointed at another classmate. The teacher turned to the student and said, “Oh, don’t come after me,” and then a female teacher looked at the student and said, “Oh, what a waste.”[63]

Kiyoshi M. told Human Rights Watch, “During my second year of junior high I was having a really difficult time with my identity. I went to talk to my homeroom teacher, and another teacher overheard us and accosted me later: ‘Oh, you like girls. There’s something wrong with you.’”[64]

The impact of these experiences on children can be harsh and long-lasting.[65] Sachi N., a 20-year-old lesbian in Nagoya who recalled being taught in health classes that homosexual intercourse was the main cause of AIDS and “a very weird thing to do,” said the impact of her peers’ and teachers’ persistent anti-LGBT rhetoric sticks with her today:

Everything I heard and was taught [about LGBT people] was bad. Even though now I am a lesbian and I know it, I still have a bad concept of it. I still think it’s my fault and I can improve it. Even though I don’t want to, I still have this lingering negative concept of it.[66]

A school counselor said the impact of the constant anti-LGBT rhetoric is devastating on the students he works with: “The fact that words such as okama or homo are used as insults, regardless of whether they are directed at LGBT students or not, is extremely harmful to kids in schools.” In his clinical experience at three different schools, the harm is inflicted on students by both the lack of objective information about gender and sexuality in formal settings and the ways anti-LGBT attitudes seep in to fill the void:

Students come in [to see me] without a vocabulary to describe themselves. They come in describing attraction to the same gender or the mean things people say about them—that’s how they’re learning about themselves, the hate, because there’s nothing about them that’s positive in the school environment.[67]

The experience of Yuri L., a 19-year-old lesbian in Nagoya, illustrates this point. She recounted:

In high school PE class the teacher pointed to a chart of a woman and asked us to recite that women love men. I didn’t identify as a lesbian at the time but it was extremely stressful for me—I couldn’t understand why but it felt very bad.[68]

The impact of anti-LGBT rhetoric also affects LGBT teachers. A gay teacher at a Tokyo high school who has never disclosed his sexual orientation to his colleagues or students explained that while he thinks his supervisors would support him being openly gay, he has witnessed so much bullying of gay and transgender students in his school that he fears the prejudiced environment would turn on him. “That’s not something the administrators would be able to help me with—the bullying from students,” he said. “That’s just something I don’t want to experience, so I stay quiet.”[69]

Japan’s national bullying prevention policy does specify that bullying includes teasing, gossiping, and ostracizing among students, and even instructs: “Teachers’ behavior should not make students hurt or not foster bullying among students.” However, the policy makes such recommendations alongside its recommendation that schools “cultivate recognition and self-confidence among students that they are part of a group” so that they “can recognize each other without being swayed by stress pointlessly.”[70] No groups of students are specifically mentioned.

Beyond hateful rhetoric that stokes animus against LGBT children and those exploring their identities, deeply entrenched cultures of impunity for bullies in Japan’s schools make LGBT students’ access to education even more precarious.

Physical Abuse

Most students with whom we spoke said that serious physical violence was uncommon. We heard the same from the Ministry of Education’s National Institute for Education Policy Research, which has tracked bullying in general for the last 12 years. “Usually bullying in the United States and Europe includes violence, hitting or kicking, as well as verbal harassment. In Japan, ijime mainly means harassment without violence,” said senior researcher Mituru Taki. Taki suggested that students avoid physical violence because teachers intervene quickly to stop such behavior:

Japanese children know that if they use violence, they will be punished. Teachers will call students out if they witness teasing or name-calling, but students know they won’t be punished as severely as if they do something physically.… If violence is involved, teachers take the case very seriously. If there’s not violence, it’s often not seen as a big deal.[71]

Human Rights Watch nonetheless heard accounts of bullying that went beyond verbal harassment. For example, there were several independent references to groups of students surrounding one of their peers and removing his trousers in public as a form of humiliation.[72]

Two students told Human Rights Watch that they had themselves experienced physical forms of harassment. In one case, Kiyoko N. said that she was accused of not being “girly enough” by groups of her junior high school classmates who regularly swarmed around her and beat her with a roll of paper. She said her teachers witnessed the abuse again and again but did nothing. In private, while cleaning the library with a small group of students after school as part of her student responsibilities, she asked her peers for advice. They told her to endure the abuse, and that high school would be easier. “It was common knowledge that I was being bullied,” she said. “It was also common knowledge that my teachers would never help me.”[73]

Toshiro Y., a gay 17-year-old boy who attended an all-boys’ school in Tokyo, told us:

In elementary school the bullying wasn’t as bad.… The boys are bigger now. They have a lot of energy, so there’s a lot of physical bullying. Like, when I first arrived, they would take my binder, all of my homework, and throw it in the trashcan, so I would get bad grades. It was very important to me to do well in school. I don’t remember everything. Just always getting food thrown at my face when we were eating.[74]

Pressure to Conform

There’s a saying here: “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down.” It means that everybody has to be the same. Just the way I was, I wasn’t accepted. It really hurt me. It really damaged me very, very much.

–Toshiro Y., 17, Tokyo, September 2015

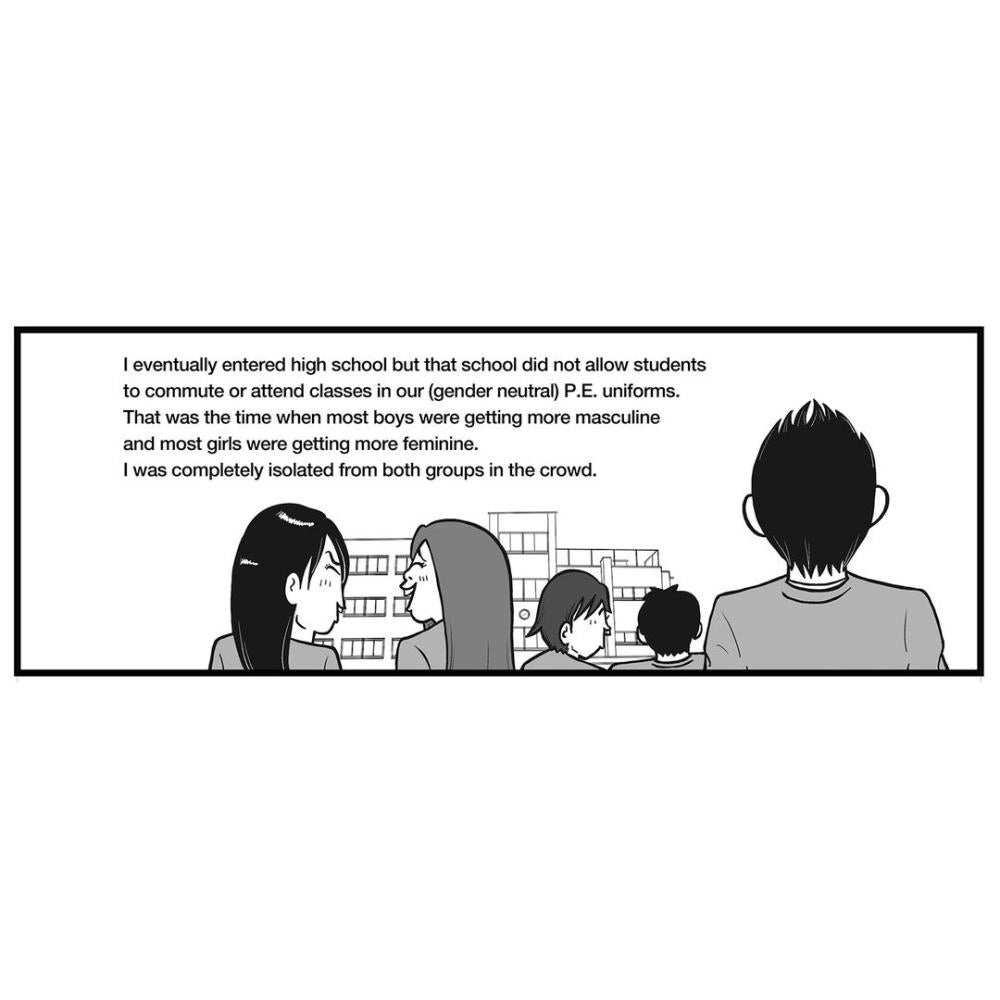

Student behavior in Japanese schools is closely monitored and controlled. Scholarly accounts of kosoku, or school rules, have described enforcement as a “shared responsibility” wherein “pupil monitoring of personal behavior and that of their classmates will obviate the need for adults to step in and discipline children who break the rules.”[75] The rules subject to peer enforcement include detailed standards of appearance and behavior. This can have particularly harsh implications for LGBT students who face both sanctioned enforcement by their classmates and anti-LGBT prejudice fueled by ignorance of gender and sexuality.

Researchers who conducted in-depth interviews with Japanese students who had admitted to having bullied their classmates found bullies were frequently motivated by thinking that their victims were “incapable of understanding how to behave appropriately.”[76] A Tokyo-based lawyer who frequently makes presentations to students about bullying made a similar observation:

I ask the students, “Do you think there’s a good reason why people are bullied?” An astonishing percentage will say yes—because the student is fat, or doesn’t act masculine enough, or is causing a nuisance to others, or is not really good at something. Or, as one bully described his victim, “He was a bit weird.”[77]

We heard much the same from LGBT students who told us they had been bullied. Eiji N., 26, said, “When you’re really little, you’re basically taught that girls should be very feminine, boys very masculine. Boys should like PE, soccer. Boys should be really active. Girls should be on the playground or gym acting giggly.”[78] Toshiro reported that pressures to conform came at a young age:

I was told physically that it was not okay to act the way I did. As early as first grade, the first day of elementary school. From such a young age I was told I was not okay, it was not okay for me to be the way I was, I’d have to be someone else. From the time I was very young.[79]

Some school officials see these rigid gender norms as deeply imbued in the institutional culture, causing staff to enforce them while unknowingly inflicting harm. A school counselor explained that he has heard teachers tell male students that their behavior is “too girlish” and female students that their behavior is too masculine:

It’s not that they intend to hurt the kid by saying this. But they genuinely believe that they are doing the right thing by correcting what they see as strange behavior, and they have no idea how they could be harming the kid.[80]

The propagation and upholding of social norms is central to Japan’s anti-bullying policy, and even appears as a suggested explicit prevention measure.

While Japan has an expansive national bullying prevention policy in place, it contains some troubling elements. For example, it promotes conformity to social norms as a core value, both implicitly in its repeated assertions that “bullying can happen to any child in any school,” and explicitly in its recommendation that schools should “enrich minds” with “an understanding of conforming to rules” as a bullying prevention measure.[81]

School Enforcement of Gender Norms

Most Japanese schools insist on conformity to strict gender norms as a matter of school policy with regard to uniforms, lavatory access, information imparted in classrooms, and other mechanisms of social norm enforcement.

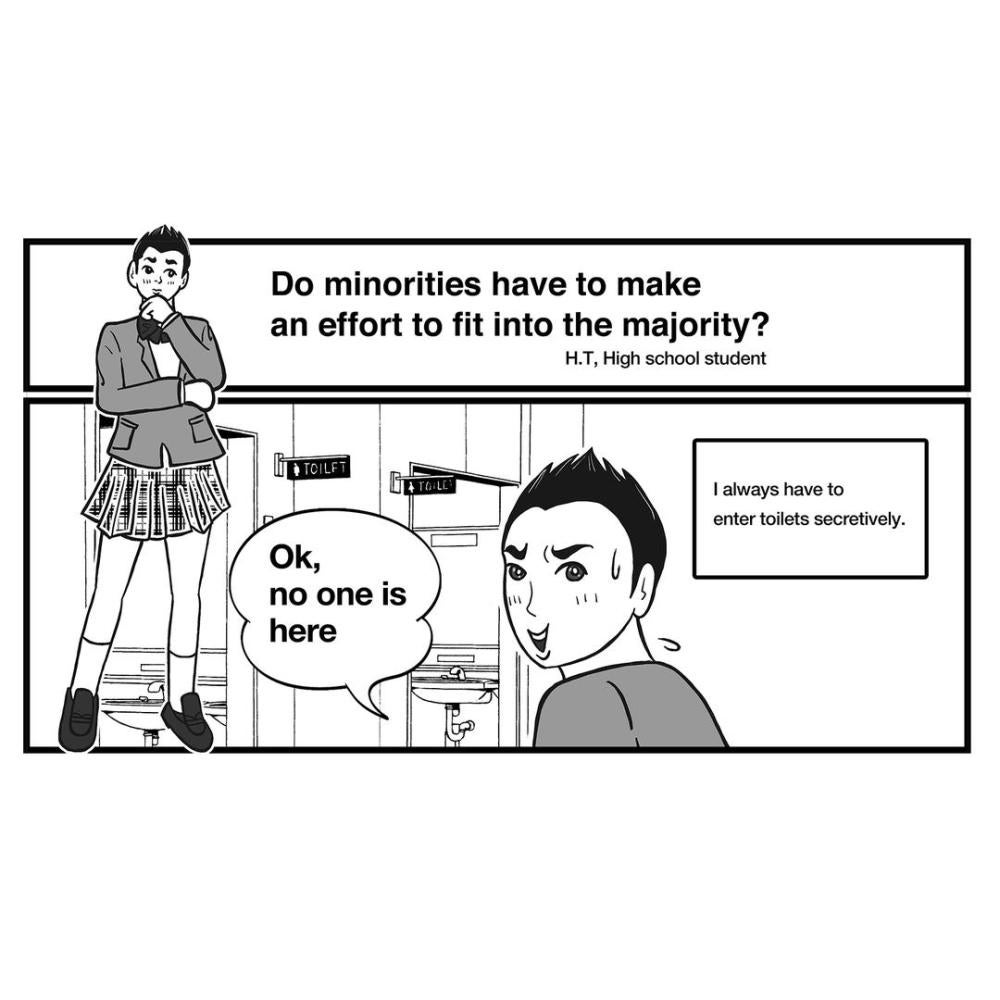

Student activities are typically gender-segregated, though the degree to which schools enforce gender roles appears to vary. The anxieties this standard system causes transgender and gender nonconforming students are intense. As one junior high student explained: “Gender segregation is everywhere in school—roll call, uniforms, seating arrangement, and hair length are all dictated by gender.”[82]

Anthropologist Peter Cave, who studies Japanese education, has noted that even in primary schools, gender differences in how students are treated and socially conditioned are apparent.[83] A transgender high school teacher told Human Rights Watch:

The Japanese school system is really strict with the gender system. It imprints on students where they belong and don’t belong. In later years when gender is firmly tracked, transgender kids really start suffering. They either have to conceal and lie or act like themselves and invite bullying and exclusion.[84]

Kaoru M., a 19-year-old transgender woman in Setagaya, explained how her school’s “firmly tracked” gender segregation left her isolated: “I expected in high school that there would be more mixing of boys and girls but there was complete social separation.” Kaoru was not allowed to wear a female uniform in high school, but wore long hair and had what she described as a “feminized appearance.” She was able to join all-girls extracurricular activities, but faced aggressive and scrutinizing questions and teasing from classmates. “I was isolated from both boys and girls. There was nowhere to go for me,” she said.[85]

Some students told Human Rights Watch that their schools, to their credit, sought and followed guidance on how to guarantee transgender students’ rights. A lawyer in Tokyo said that several schools in the city had consulted with him on issues such as uniforms and lavatory access when they became aware that they had transgender students, and as a result agreed that students would be able to wear uniforms and have access to lavatories and school activities according to their gender identity.[86] Such approaches by schools appear to be the exception rather than the norm.

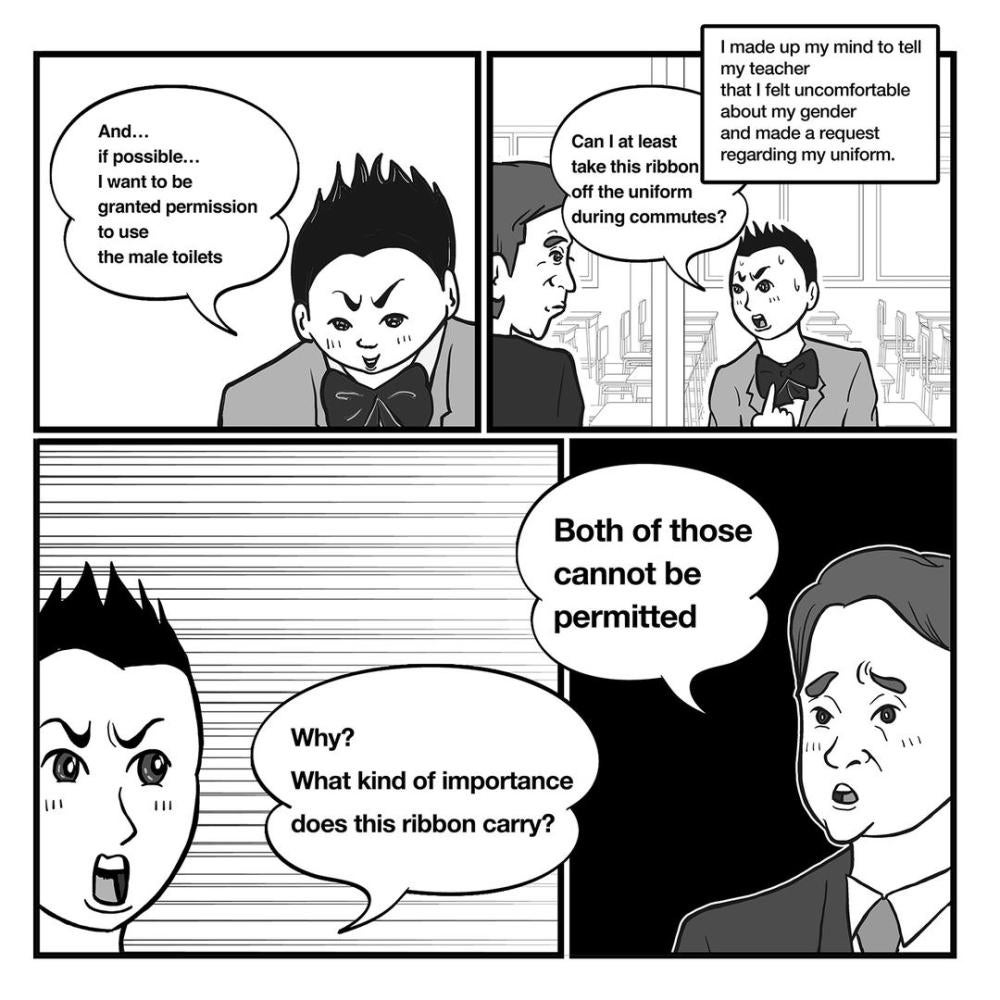

School Uniforms

The vast majority of Japan’s junior high and high schools require students to wear uniforms. The attire is gender-specific and the two options, male or female, are dispensed to students according to the sex they were assigned at birth. “The dress codes are usually very strict,” said Mameta Endo, a transgender man who has worked on issues facing LGBT youth in Japan. “The idea behind the uniform is that if you can’t wear it properly, you’re a bad student. It makes you an outcast.”[87]

In some instances Human Rights Watch documented, students were able to request alterations to their uniforms; in a few cases, students were able to request a full switch of the uniform according to their gender identity. “Schools are really starting to be flexible,” a Tokyo-based lawyer said.[88]

In many cases we identified, however, agreements to alter uniform requirements were not the result of consistently applied policies designed to respect students’ right to free expression of their gender identity, but rather of the compassion of school officials, assiduous advocacy by parents, or in some cases the student’s presentation of their diagnosis with gender identity disorder (GID). For some transgender students and other children exploring gender identity, the strict uniform policy was an acute source of anxiety, leading to extended school absences and even dropouts. As the Osaka-based psychiatrist Jun Koh told Human Rights Watch:

In the transition from elementary school [which typically does not require uniforms] to junior high school [which does require them], transgender students start having difficulties. Kids who had questions about their birth-assigned gender earlier in life often don’t seek counseling until they have to start wearing school uniforms—it’s the structure that forces them to feel bad, and it intensifies their anxieties.[89]

For example, Takeshi O. explained that his anxieties about the female gender of his school uniform increased over time. “When I first started junior high school I didn’t question the uniform initially,” he said. “I progressively started to question it and by the third year I dreaded every school day because it meant I would have to put the skirt on.”[90]

Students who attempted to request to change their uniform faced various challenges. Akemi N., an 18-year-old transgender man in Okinawa, told Human Rights Watch that when he was 16 years old the high school administrators told him he would need to show a certificate of diagnosis for GID in order to change his uniform.[91] He was able to obtain the GID certificate within a few weeks, but when he presented it to school officials they denied his uniform change request on the grounds that there was no precedent for them to follow.[92] According to Koh, “Most kids I work with talk about how they just want to be in an environment in which they can freely express themselves in their preferred gender, including in the way they dress.”[93]

A lack of explicit support for identity-based uniform selection leaves transgender children to work out their own solutions.[94] A 12-year-old transgender girl in Osaka explained that while she wears skirts on weekends and at home because she feels safe to express herself around her friends and parents, she continues to wear the boys’ uniform at school because she is not confident that the teachers, even if she requested it, would support her transition. “It’s the fear of being bullied by other students that leads me to stay in a male uniform,” she said.[95]

For other students, the arbitrary implementation of school uniform regulations subjects them to a confusing maze of rules and disturbing responses to their requests. For example, Mitsu M., a 17-year-old transgender boy in Hamamatsu, said that while his junior high teachers allowed him to wear the gender-neutral physical education outfit at school as long as he wore the female uniform skirt while traveling to and from school, his high school then forced him to wear a skirt all day—leading him to drop out.[96]

Rei N. said her junior high school rejected her requests to change uniforms for two years. “I told the school officials that if they didn’t let me dress like that I wouldn’t come to school,” she said, explaining that they subsequently allowed her to wear the girls’ uniform top and physical education pants as a compromise.[97]

Natsuo Z., an 18-year-old high school senior attending a correspondence school in Fukuoka, said that they dropped out of public school during the second year of junior high because “wearing a uniform became unbearable.”[98] They continued:

School uniforms are meant to function like military uniforms—to promote conformity and subtly imply that being different is a bad thing. But because there is no actual justification for the uniforms, when people challenge them we are met with vague answers about honor, harmony, and public morality.[99]

Other interviewees explained how school uniform policies led them to avoid enrolling in conventional schools even when their entrance test scores made them eligible, instead opting for less rigorous alternatives such as correspondence schools that did not require uniforms.[100]

But while uniforms were a common flash point for anxieties among interviewees, other aspects of appearance also triggered deep-seated gender stereotypes that Japan’s schools promote. For example, one interviewee said that starting in junior high school his classmates teased him mercilessly, including by spitting on him, making specific reference to his long hair. “I cut my hair after a while, in junior high. I had a crew cut. Once I had the crew cut, the bullying ended, but I also felt like I could no longer be myself at all,” he said.[101]

Lavatories and Changing Rooms

The directive from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) about responding to students diagnosed with gender identity disorder suggests that teachers accommodate transgender students by “[accepting] the usage of staff and multi-purpose toilets.”[102]

We learned of schools that have taken this approach. For example, when a 12-year-old transgender girl in Osaka told her junior high teacher she did not want to use the boy’s bathroom any more, the teacher suggested she use the private staff bathroom in the basement.[103]

Some schools take a similar approach to changing rooms for physical education classes. Minato J., 18, said that when he told his teachers he identified as male, his physical education teacher decided that he could change alone in the teachers’ changing area.[104]

However, these approaches have not been a positive experience for all students. Hirohito O., a 16-year-old transgender boy in Fukuoka, said:

When I went to the boys’ bathroom, the boys would say, “But you’re a girl,” and tease me. When I went to the girls’ bathroom, the girls would say, “But you’re a boy,” and tease me. When I went to the teacher genderless bathroom, all the students would call me “disabled.”[105]

Such approaches may also place transgender students at a disadvantage with respect to their peers. As Emi T., 13, said, “When I was in 1st year [of junior high school], they designated the disability toilet for me. They said I would have to use that toilet. It’s difficult to rush from the 1st floor toilet to the 4th floor.” She continued:

To change my clothes, they have also designated the disability toilet as my changing area. I change there for PE. It’s far away, but there’s nothing I can do about it, because I can’t change with the other students. When I change into my bathing suit, I have to walk all the way from the toilet in my bathing suit. I feel embarrassed in front of the teachers and other students. I walk 150 meters from the toilet past the teachers’ room and the workshop to the pool.[106]

Other schools require transgender students to use the toilet and changing rooms that correspond to the gender that appears on their school records, usually meaning that they must use facilities that do not correspond to their gender identity. For many transgender students, such rules are profoundly at odds with their sense of self, and may cause deep humiliation. Madoka R., a 15-year-old transgender girl in Osaka, said, “I couldn’t bear going to the boys’ toilet, so I wanted to choose the girls’ toilet.… About changing clothing, I didn’t like to see the boys naked, and I didn’t want the boys to see my body.”[107]

Studies have shown that students who do not feel comfortable accessing restrooms because of bullying and discrimination on the basis of their gender identity have reported avoiding using the lavatories at schools.[108] This can lead to dehydration, bladder infections, and kidney problems when they are unable to safely access a bathroom in accordance with their gender identity.

In addition, transgender students have been regularly deterred or excluded from participating in physical education classes and athletics that are important for adolescent development. In Osamu I.’s case for example, his physical education teacher’s decision to force him to use a staff office instead of the boys’ or girls’ changing room, without consulting him as to what he would prefer, led to students teasing him more frequently, and subsequently his absence from physical education classes.

For students who courageously expressed their gender identity while still ascribing to rigid gender-segregated dress codes and facilities, the consequences could be harsh. “Once I used a female bathroom and students checked the sign and then harassed me,” said Mitsu. “They demanded to know why I looked the way I did, so masculine with short hair, and still used the female bathroom.”[109] As Emi’s mother remarked:

The treatment by the school, their control of the situation, the toilet, the clothes-changing—these became big issues. I treat my child as a girl. I tell her, “You are perfectly fine to go use the girls’ toilet. Just do it.” But the teachers will stop her. I feel frustrated. Why do you want to stop her? “It’s school rules,” they say. “Think about how it looks to society.”[110]

Such rigid enforcement can also be exploited by students who bully or harass their transgender peers. For example, Madoka R. described an incident that took place when she was in the 6th grade and a teacher reprimanded her for using the girl’s toilet while dressed as a boy:

After talking to me for a few minutes the teacher shouted at me: “You’re going to the girls’ toilet!”… I was crying and crying on the way home. I was most upset because everybody thought I was a boy. I was so angry and disappointed in the teacher and the other students, and so angry that I was forced to lie by going to school as a boy. The teacher did not support me. After that, I stopped going to elementary school.[111]

School Activities

Many schools in Japan have activities that are divided by gender. Physical education, for example, is often taught to boys and girls in separate classes. We heard that some schools allowed students to attend the class that corresponded to their gender identity. For instance, Emi told us that she was taking physical education classes with girls.[112]

But we also heard of transgender students who are told they are assigned to class based on their school records. For example, Madoka said that she was removed from physical education classes after she told her school that she identified as female and tried to switch to one of the girls’ gym classes:

I wanted to join the girls for gymnastics. Instead, the school decided I would take private lessons in a different room with a private teacher. The content of the lessons was homework with a private teacher. So I’m not really going to gymnastics class at all. I continued to ask the school to change to the girls’ class. They declined until the end of my second year.[113]

Disorder-Based Directive

The 2015 MEXT directive, “Regarding the Careful Response to Students with Gender Identity Disorder,” focuses on diagnosing children with a mental disorder as a pathway to their inclusion in schools, and on medical institutions as the primary source of information about gender and sexuality.[114]

While the directive encourages teachers to develop their understanding of transgender students’ experiences, and even encourages teachers to accept students’ attire or hair style because “it might be because of [the student’s] gender identity disorder,” the document is an inadequate and even harmful policy response. The directive reflects a disturbing reliance on the pathologizing and discriminatory model for transgender issues enshrined in the Act on Special Cases in Handling Gender for People with Gender Identity Disorder, or Law 111 of 2003—the law governing legal gender recognition for transgender people in Japan.[115]

The law requires a diagnosis of gender identity disorder (GID) as the first criterion for all candidates for recognition before the law in their appropriate gender. GID is defined in the law as “a person, despite his/her biological sex being clear, who continually maintains a psychological identity with an alternative gender, who holds the intention to physically and socially conform to an alternative gender.” The process requires the person to be “medically diagnosed in such respects by two or more physicians generally recognized as holding competent knowledge and experience necessary for the task.”[116]

The process can have a particularly intense negative impact on children learning about and exploring their gender identity. This is in part because the law includes a mandatory age of 20 for achieving legal gender recognition, and extra steps for people under 20 years of age to obtain the GID diagnosis, the first step in the process. These factors are compounded by the GID diagnosis requirement to hold “the intention to physically and socially conform to an alternative gender,” which puts intense pressure on people to conform to gender stereotypes at the expense of their integrity, privacy, and autonomy.[117] It is also reflected in how Law 111 of 2003 has been interpreted by the government with regard to gender nonconforming children. For example, the 2015 MEXT directive instructs:

The diagnosis and advice from medical institutions is a very crucial opportunity for the school to get professional knowledge. It is also helpful as it can serve as a basis for explanation for teachers and other students and guardians. Even when students express their anxieties with their sexuality, it is not always the case that they have appropriate information on the issue. It could also be the case that their anxieties are being confused with other issues. Thus it is essential for schools to cooperate with medical institutions.[118]

Both the age restriction and the rigid medical criteria inflict significant harm on young people who instead need information, support, and safe spaces to explore and express gender—all elements of inclusive and supportive schools.

The directive addresses the issue of school uniforms in a list of “examples of support for students with gender identity disorder” by suggesting that teachers should “accept students’ preference of outfit, school and gym uniform.” Regarding lavatories, the directive suggests teachers accommodate transgender students by “[accepting] the usage of staff and multi-purpose toilet.”[119]

In addition to the fact that the directive is based on a medical model that refers to children exploring and expressing their gender identity as “disordered,” the directive’s examples of support for schools to follow are not binding policy or protocol recommendations, but illustrations drawn from a diagnostic model.[120] The MEXT “Guidebook for Teachers Regarding Careful Response to Students related to Gender Identity Disorder as well as Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity,” issued in April 2016, clarifies that schools should not compel transgender students to visit medical facilities, and reiterates that it is possible to accommodate students who do not have a GID diagnosis. However, in this document MEXT continued to advise schools to base such accommodations at least in part on students’ medical consultation history, and repeated that schools should seek advice about GID students primarily from medical institutions.[121]

Human Rights Watch interviews with transgender children in Japan revealed that school officials issue varied responses to transgender students’ requests to use facilities according to their gender identity, and cases which have occurred since its issuance reflect a piecemeal implementation of the MEXT directive.

|