You were there when the treaty establishing the ICC was completed 20 years ago. What was that like?

It was a six-week rollercoaster ride of intense negotiations, preceded by three years of negotiations at United Nations headquarters in New York to create a draft treaty. There were ministers and lawyers from probably 150 countries around the world, and nongovernmental organizations from around the world, too.

I got to Rome filled with excitement. Really, we were looking at accomplishing a task that was so urgently needed. You have to remember, this was directly after the horrific conflict in the former Yugoslavia, where there was genocide in the mass execution of 8,000 Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica. It also followed on the Rwandan genocide, when in a three-month period about 800,000 Tutsis were slaughtered. The world was reeling and it needed a permanent criminal court that could deal with these kinds of horrors wherever they occurred.

All of us felt we were there in a history-making event and moment.

And there was also the uncertainly of whether at the end of the five weeks – it was going to end on July 17 come hell or high water – there would be a treaty establishing a court worth having. Were we going to succeed? Fail?

What was your role in helping establish the court?

Civil society groups, including Human Rights Watch, had a lot to say about provisions that would be part of a final treaty, specifically the powers of the court and its officials. We had a say in what war crimes could be included, for example which crimes committed in civil wars.

We were not formally included in the negotiations. But another role for Human Rights Watch and colleague groups was to share strategy and tactics with the 70 or so countries that wanted to create a fair, independent, impartial, and effective court. We shared thoughts on ways to circumvent obstacles thrown up by some of the less supportive countries, like China, Saudi Arabia, and India. Also, the United States posed its own demands.

We also spoke to the media. We could say things that official delegations would not say and stigmatize certain governments that were being particularly obstructive.

The ICC’s current chief prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, is seen as someone who diligently works to uphold the rule of law, all while a new generation of world leaders are busy trying to tear down institutions.

Unfortunately, the first prosecutor of the court made significant mistakes. He shortchanged the importance of serious, careful investigations. This meant that several of the charges and cases he brought during the court’s first decade were tossed out. Those cases were further undermined by witness tampering, with some witnesses disappearing and others possibly killed. This includes the now-dismissed case against Kenya’s current president and deputy president involving post-election violence. There were cases in the Democratic Republic of Congo that were similarly tossed out.

This was a real problem. The first impression created by the ICC was not terrifically positive.

The current prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, started work in 2012. She is quite different, in that she actually bases her actions, and the actions of her office, on the requirements of the Rome Statue itself. Investigation is taken much more seriously. Getting the facts. Double-checking the facts. She conveys a sense of commitment to the law. A commitment to the victims in the communities most effected by the crimes, and a carefulness that is very important.

Which is not to say that the Office of the Prosecutor, or the court, does not still have challenges.

Like the fact that some countries are not parties to the ICC because they haven’t ratified the treaty. So the court’s justice isn’t universal.

When the ICC was founded, it was shortly after the end of the Cold War, the end of apartheid in South Africa, the transition to democracy in many Latin American countries, and the end of dictatorship in South Korea. Some even thought, what will be the need for this court?

Contrast that with today. What’s happened in Syria. What’s happened in Iraq, what’s going on in Yemen. The civil war in South Sudan and the ethnic cleansing of 700,000 Rohingya Muslim in Myanmar. We see the proliferation of the ugliest kinds of crimes that the ICC was created to address.

Yet the ICC cannot address them because none of the countries I just mentioned – not surprisingly – have ratified and joined the ICC system. And thus, these crimes unfold and the court’s prosecutor has no authority to intervene unless the UN Security Council – without any of its five permanent members casting a veto – asks the court to get involved.

Why was the court designed this way? An important concession was slipped in to make the ICC appear less threatening to the US government. This happened at the last minute, very quietly, and was then presented as a fait accompli. And of course the US didn’t join anyway.

The upshot, essentially, is that for the prosecutor to begin an investigation in a country, it is necessary for that country to have ratified this treaty. Nearly two-thirds of the UN membership – 123 states – are party to the treaty. Among the exceptions are the largest and most powerful states: China, the US, Russia, India, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia.

The only other way for the ICC to reach these countries is if their forces commit crimes on the territory of a country that has joined the ICC. For example, there is evidence that US military forces and intelligence personnel committed war crimes on Afghan soil. In 2004 the government in Kabul decided to ratify the treaty. That’s why alleged US crimes in Afghanistan are a focus of the ICC.

And it’s not just Afghanistan. The ICC is on the cusp of a shift away from where it traditionally operated in Africa to opening preliminary examinations in the Philippines, Venezuela, and other countries.

There is a shift that’s taking place. The court carried out all of its first investigations in Africa, in most cases at the request of the countries themselves, with two others at the request of the UN Security Council. Some African leaders said the ICC was unfairly persecuting Africa. I think abusive leaders used that as a self-defense tactic. But it had resonance because of the dreadful centuries of Africa’s colonial history, where the continent and its people were ravaged by European powers.

So, then you have the president of Kenya saying the court was a tool of neo-colonial powers.

I think this prosecutor sees her legacy in part as bringing the court out of Africa. She has requested opening investigations in Afghanistan, which implicates the US. She has opened an investigation in Georgia in the Caucasus, which may implicate Russia. In the case of Palestine, she may open an investigation into settlements in the West Bank that would implicate Israelis.

This is an effort to realize the promise and potential that inspired so many of us in Rome. We were creating a court that could reach people from the most powerful countries, as well as the less powerful states, wherever horrific crimes have been committed.

Does the ICC have the resources to do this?

I think they are stretched very thin. And that’s in part because the major contributing governments – France, Germany, the UK, Japan, Canada, and Italy – refuse to increase the court budget commensurate with the demands. These governments want to limit the court’s budget increases to keeping with inflation when the number of countries where the court is investigating, or deciding whether to investigate, has increased dramatically.

The court’s budget of 150 million euros per year is a lot of money, no doubt. But it costs a lot less than a month’s UN field operations in some war-torn countries.

Can the court manage without additional resources?

Yes, but in a more restricted way than the court’s treaty intended. The question, though, is whether in diversifying its investigations it will step on the toes of very powerful countries. And the sheer obstacles of doing this difficult work well with limited funding. Will the ICC be able to rise to the challenge? These are the stakes for 2018.

Is the court strong enough to withstand the attacks on the rule of law happening throughout the world? After all, these are coming from both authoritarian countries and democracies headed by autocratic populists.

The governments that created this court 20 years ago need to convey publicly, to their own people, why the court, with all its operational shortcomings, is important. And they need to increase the support – politically, diplomatically, financially – for this institution. That’s what this 20th anniversary should be about.

Why do you see the court as essential? People are still committing horrible and cruel crimes.

The court will not cure and correct all the cruelty and crimes human beings inflict on one another. But there is a clear lesson to be derived from history. Overwhelmingly, with one or two exceptions, when these crimes occur, if there is no proper accounting for them – no impartial trials – the same crimes will likely erupt again in an uglier, more intense way.

Trials are essential, along with truth telling, documenting crimes, providing reparations, and ridding security forces of people who committed grave crimes. As is fostering the development of war-torn countries in the context of a durable peace.

So, you ask me what’s the importance of the court? First and foremost, it’s a matter of honoring the victims and their memory by holding to account those found to be responsible for their suffering. I think that’s a mark of civilization. But pragmatically speaking, if you want to prevent the recurrence of such crimes, these trials and other measures are crucial to prevent another, even more vicious, cycle of violence.

Why are you so dedicated to International Justice?

I’m a human rights activist, first and foremost. Have been for decades. I was trained professionally as a lawyer. And I’ve seen the role that law can play in advancing and defending human rights. I think that with its weakness and shortcomings the court still represents a qualitative advance in the rule of law and the protection of human beings.

What’s in it for me? I think that at the end of the day, it’s that. Of the advances this represents. The importance of improving the practice. Not just growing cynical. Or skeptical. Not letting those who fear accountability have their way to commit heinous crimes without fearing being held responsible. That’s what keeps me in there.

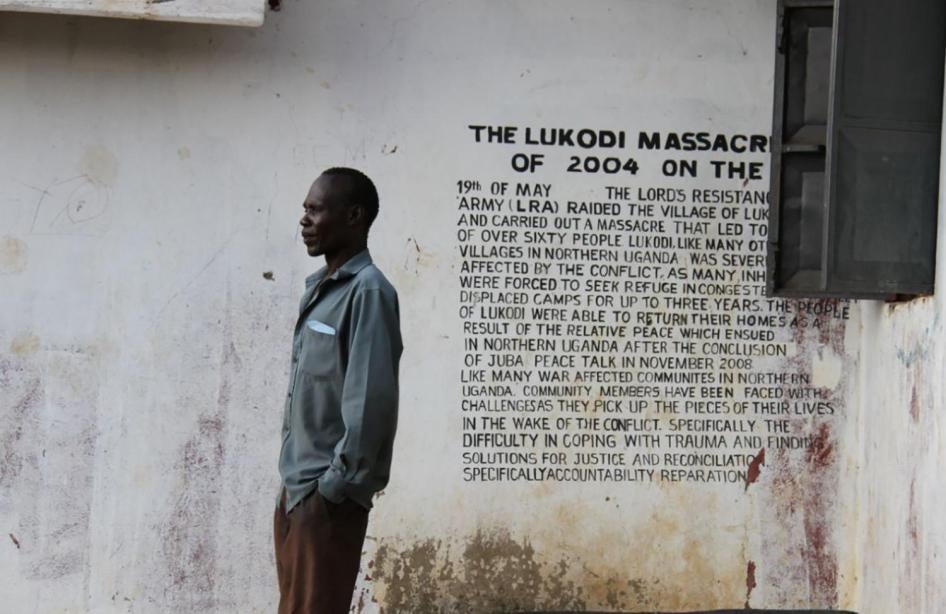

And the people I’ve met, in the camps for displaced people in northern Uganda and northern Mali, or the survivors of the genocide in Srebrenica, or the victims of the limb amputations in Sierra Leone, or the Iraqi victims of Saddam Hussein. I mean, that’s the fuel. That’s what’s driving me.

This interview has been edited and condensed.