(New York) – Cambodia’s parliament enacted amendments to the constitution and penal code that will further consolidate the ruling party’s power and stifle free speech, Human Rights Watch said today. Cambodia’s donors should publicly state that these continued moves towards a one-party state will have serious political, economic, and diplomatic consequences.

With the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) dissolved, the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP)-controlled National Assembly unanimously passed the amendments on February 14, 2018, following ratification by the Council of Ministers in early February. The changes next move to the rubber-stamp Senate for approval before being signed into law by King Norodom Sihamoni.

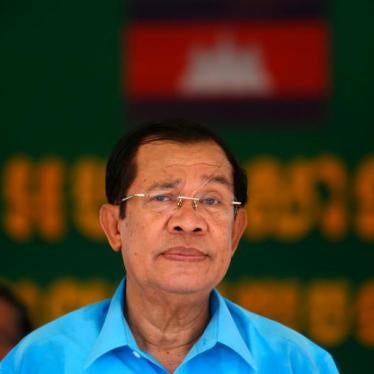

“Piece by piece, Prime Minister Hun Sen has constructed a legal and political system to cement himself as the country’s sole authority, without threat of opposition or dissent,” said Brad Adams, Asia director. “These amendments are the latest marker of his shift toward barefaced authoritarianism. The mask of democracy is off.”

The National Assembly passed amendments to five articles of the Cambodian constitution that tighten restrictions on voting rights and freedom of association and require every Cambodian citizen to “respect the constitution” and “defend the motherland.” Article 34 was changed to allow new restrictions on the right to vote, while Article 42 now gives the government authority to take action against political parties if they do not “place the country and nation’s interest first,” an amendment designed to target opposition parties. Article 53, which now states that Cambodia cannot interfere in the internal affairs of other countries since it opposes foreign interference in its own affairs, also appears to target the CNRP, which regularly appealed to donors and the United Nations to put pressure on the Cambodian government to hold free and fair elections and impose sanctions.

Additional election-related amendments were approved which restrict the Constitutional Council’s authority to process complaints from political parties that have been denied registration by the Ministry of Interior.

“These amendments are clearly aimed at shutting up the opposition and imposing penalties on any attempt to appeal for international assistance to reverse Hun Sen’s creation of a new one-party state,” Adams said. “They also open the door to further law-based restrictions on basic rights.”

Revisions to the penal code include a lese majeste (insulting the monarchy) provision that carries a penalty of one to five years in prison and a fine of up to US$2,500 for individuals, and $12,500 for legal entities. The law is an additional avenue for the government to pursue politically motivated prosecutions at the expense of free speech in Cambodia. “We created the law to make people scared,” said Interior Ministry spokesperson Khieu Sopheak, in reference to the new provision.

Justice Ministry spokesperson Chin Malin said the CPP drafted the lese majeste law to “prevent and punish, in order to protect the dignity and the fame of the king.” Yet Hun Sen’s own approach toward the monarchy over his 33 years of rule has been one of minimization and contention. Hun Sen declared after his longtime political rival Norodom Sihanouk abdicated that the former king would be better off dead, and has severely restricted the current king’s presence and role to curtail any potential political threat.

The lese majeste law comes on the heels of a defamation case against former Deputy Prime Minister Lu Lay Sreng, who was sued by Hun Sen for comments he made in a leaked phone call criticizing the king and the CPP. He was found guilty in absentia on January 25 and ordered to pay Hun Sen US$125,000.

Thailand’s government has long abused its draconian lese majeste laws to arbitrarily detain critics, journalists, and activists, who often face long prison sentences and denial of bail. This has sharply constrained free expression in the country, including increasing restrictions on social media. Since the May 2014 military coup, at least 105 people have been arrested in Thailand on lese majeste charges.

The UN Human Rights Committee states in its General Comment No. 34 on the right to freedom of expression that lese majeste laws “should not provide for more severe penalties solely on the basis of the identity of the person that may have been impugned,” and that governments “should not prohibit criticism of institutions, such as the army or the administration.” The UN special rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression, David Kaye, stated in February 2017 that “lese majeste provisions have no place in a democratic country.”

With national elections slated for July 2018, the CPP has increasingly abused the justice system to prosecute opposition leaders and activists and suppress independent voices. The political crackdown reached a new peak in November 2017 with the dissolution of the CNRP, the main opposition party, and the ensuing redistribution of its 55 parliamentary seats. The CPP has used its expanded bloc in the National Assembly to pass legislation that shores up its political control. The revisions to the penal code and constitutional amendments were ratified with a unanimous vote from the 123 assembly members, with full support from the royalist party Funcinpec, which took over most of the CNRP’s seats, in addition to the CPP’s majority.

The new amendments suggest the CPP will further its crackdown via legislative means. After a National Assembly meeting on February 13 to discuss the amendments, a CPP spokesperson told reporters: “Cambodia needs to have a law in the future to protect the country’s leaders because since 2012, people have been using social networks to foment a color revolution.”

“As the national elections draw near, Hun Sen is flexing the unchecked power he’s long claimed for himself,” Adams said. “Targeted, concerted efforts from concerned governments are needed for any chance of deterring further repression made easier through these new provisions.”