“My sister finished the first year at school, but then she got tired and decided to leave. She walked four hours each way every day, so that made her tired,” Sabina, 12, who grew up in rural Balkh province, said. Sabina was able to study starting at age 10 after her family moved to the city of Mazar-i Sharif. Her sister, after leaving school, married at age 15 or 16.

We’d planned a quick investigation about girls’ education in Afghanistan—a snapshot of how things stand 16 years after U.S.-led forces toppled the Taliban. But 249 interviews later, my colleagues and I had sunk deep into an issue deserving not a snapshot, but a much deeper dive.

According to the Afghan government—often criticized for disseminating overly optimistic statistics—3.5 million children are out of school, 85 percent of whom are girls. Our interviewees were mostly girls who have missed out on getting an education, and they had a lot to say.

Many had struggled desperately to study. Others had families who fought for them—moving across town or across the country to find schools, or sending them far away to live with relatives near a school. Some older brothers had made the dangerous trip to work illegally in Iran to send money home for their sisters to study. Entire families conspired to sneak some girls to school daily under the nose of a father opposed to girls’ education.

Girls young enough to be playing with toys knowledgeably discussed Taliban attacks on education, bombings, and the performance of the Afghan army. They told of family members killed and wounded, family members who fled the country for safety, and parents who never recovered from the death of a child. They described their own flight, within the country and across borders, and how that had sabotaged their education.

They described their work—weaving carpets, sewing, embroidery, or running a household—and how that prevented them from studying. Too many described having been married as children, and how marriage or even engagement ended any hopes of an education.

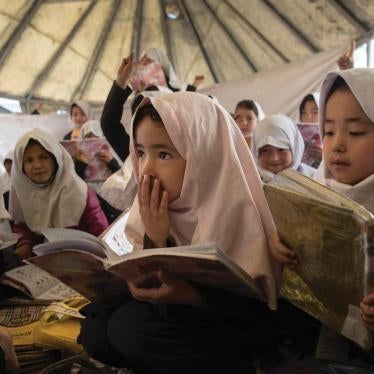

They talked about how the school system had let them down. Many missed school because there was simply no school within reach. Girls and boys usually study separately in Afghanistan, and the government provides fewer schools for girls than boys. In one case, we found a school with several new buildings paid for by international donors where, after the buildings were completed, the government changed it from a mixed gender school to a boys’ school—and moved the female students into a vacant lot next door to study in tents.

Other girls are barred by family from attending because the teachers are men; only half of Afghanistan’s provinces have more than 20 percent female teachers. Again and again girls talked about poverty: Tuition in government schools is free, but the need to pay for pencils, notebooks, schoolbags, and uniforms puts school out of reach for many.

Yet these Afghan girls are fighting every day to study.

Zarifa, 17, went to a class of 30 to 35 girls in her Kabul neighborhood set up by a nongovernmental organization, then transferred to a government school. She said many classmates drifted away. “Very few stayed,” Zarifa said. “Some married, some families didn’t allow them to continue, some had security problems.”

The environment at the government school was difficult. “There are too many students—it’s hard to manage them,” Zarifa said. “There is a lack of chairs, of teachers, of classrooms. It’s too crowded—some study in tents. There is a lack of books. At one time, I had no books.” Six years later, only 8 to 10 of the original 35 girls who started school with her were still studying. “I didn’t allow myself to be taken out,” Zarifa said. “I had promised to stay and finish.”

Some girls had a chance to catch up on missed schooling when an NGO-run community-based education program opened nearby. But these schools came and went with changes in donor funding; within the same family often some sisters were educated and some not, due to the unreliable cycles of funding for NGOs. Integrating these schools in the government education system, with sustainable funding and quality controls, would be a lifeline for many girls.

The research gave us a glimpse of the day-to-day erosion of security. I lived six years in Afghanistan without ever needing to wear a burka, but spent much of this research sweating under one in the summer heat because foreigners being seen visiting could endanger a school’s safety. Some NGOs asked us to stay only a half hour at each site for security reasons. At one school we visited, staff said a man was killed by the Taliban nearby that day, and a boy had been killed the day before. In Kandahar, we interviewed the deputy governor, a respected reformer involved in founding a youth political movement. He was killed in a suicide bombing several months later.

The proportion of students who are girls is falling in some parts of the country. By age 12 to 15, two-thirds of girls are out of school. Only 37 percent of adolescent girls can read, compared to 66 percent of adolescent boys.

International donors are eager to extricate themselves from Afghanistan, but a rushed exit will mean abandoning girls like Sabina and Zarifa. The Afghan government is fighting simply to survive. But there are steps the government can take to help girls learn right now—encourage donor funding for education, ensure access to free primary and secondary education by providing all needed school supplies, hiring and deploying more female teachers, rehabilitating and building new schools, and building on successful models that allow girls to study even amidst war.

Afghanistan’s girls are fighting to learn—they need their government and its donors in their corner. Below see one piece of the project, an eye-opening documentary that we made along with filmmaker Sediqa Mojadidi and photographer Paula Bronstein for Human Rights Watch. In it you’ll see the girls we spoke with and hear them in their own voices, tinged with regret and hopelessness, talking about why they either never went to school or were forced to abandon their education.