“I went [to school] for 10 days but then there was no one to collect cartons [for money to support my family] so I stopped.... I wish I had gone. School was good, if I had continued, I would be better off.

Losing the War

for Girls’

Education in

Afghanistan

By Heather Barr, Women's Rights Senior Researcher Photographs and footage by Paula Bronstein for Human Rights WatchI was living in New York City on 9/11. I watched from my rooftop as the second tower fell, joined colleagues handing out water to survivors covered in dust and sometimes in blood, and went to a protest in Union Square calling for peace. We knew war was coming—that the US government would respond with force—we just didn’t know yet where the bombs would fall.

As it became clear that Afghanistan was in the crosshairs, we heard a lot about Afghan girls. Under Taliban rule they weren’t allowed to study-or even go outside by themselves. Older girls and women were forced to wear the billowing blue burkas that featured in photos accompanying virtually every article.

Birds fly over Afghanistan’s capital, Kabul. The security situation in the country has grown steadily worse in recent years. Fighting in the country has escalated, with the Taliban now controlling or contesting over 40 percent of Afghanistan’s districts.

The war happened, the Taliban fell, and Afghans started rebuilding, as they had so many times before. There was donor money for girls’ education, and many good intentions, and there was progress.

I moved to Kabul in 2007. Every afternoon hundreds of girls, in black uniforms and white headscarves, poured out into the street near my house. It was impossible to see them-giggling and roughhousing, buying bolani, stuffed flatbread, from the street vendor who set up every day-and not feel that they were the future of Afghanistan, and that foreign intervention, if it had given them that chance, had to be worth something.

Insecurity

A member of Afghanistan’s security forces patrols on a hill overlooking Kabul. In recent years, security has steadily worsened across the country, including in the capital, which has repeatedly endured attacks targeting civilians. Many families struggling to educate their children face dangers such as gun battles, targeted attacks against girls' education, bombings, kidnapping, harassment, and common crime.

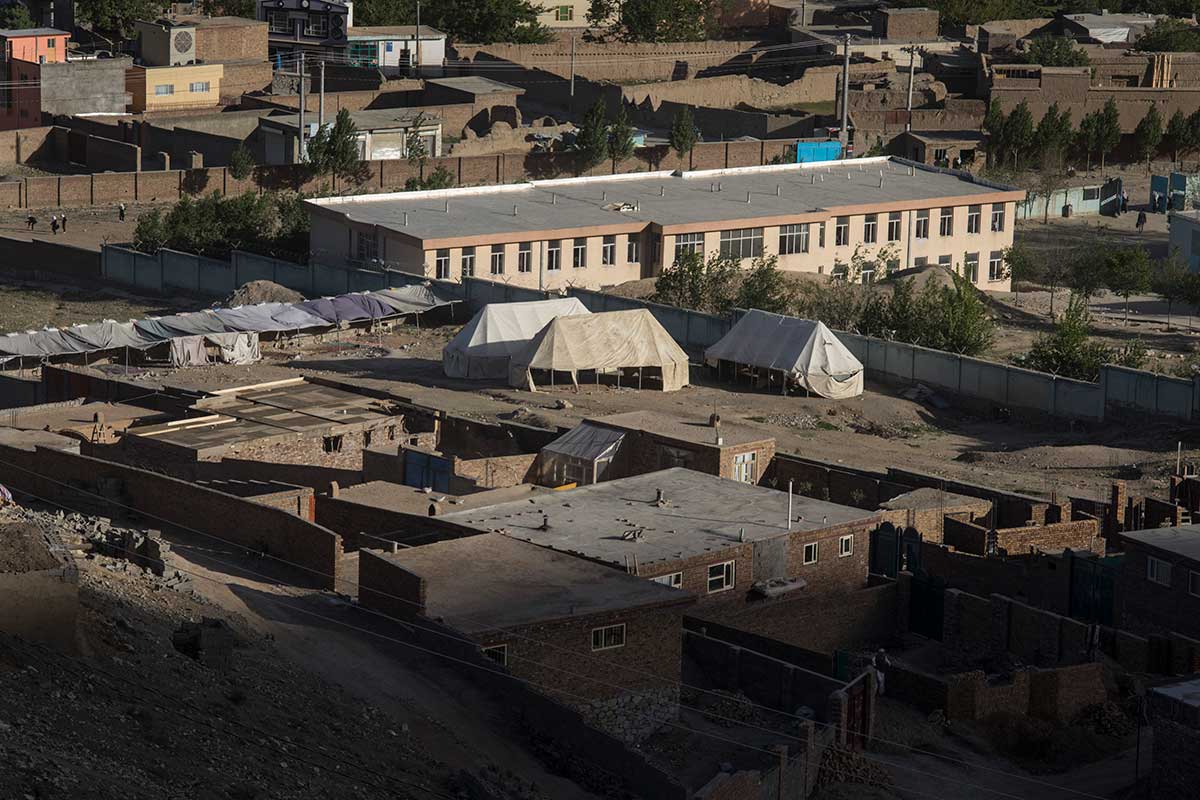

Razor-wire surrounds a government school in Kabul, Afghanistan. Rising insecurity discourages families from letting their children leave home—and families are usually more reluctant to send girls to school in insecure conditions than boys.

Poverty

Plastic bags are spread out to dry near a house in Kabul. Families who are extremely poor sometimes burn plastic as fuel for cooking and heating. Although government schools do not charge tuition, families of students at government schools are expected to provide supplies, which can include pens, pencils, notebooks, uniforms, and school bags. These indirect costs are enough to keep many children from poor families out of school.

Child Labor

A girl, 14, in the workshop where she is employed as a seamstress. She arranges her work hours around attending a government school, where she is in class seven.

A 10-year-old girl sorts through rubbish to salvage plastic containers that she can sell. She leaves home at 6 a.m. and returns at 5 p.m. She does not go to school and works to help support her large family that includes nine brothers and four sisters. None of her siblings attend school.

Two sisters, ages 9 and 5, work on the streets of Kabul selling chewing gum, earning about US$2 per day. At least a quarter of Afghan children between ages 5 and 14 work for a living or to help their families.

Displacement

Children play along the dirt roads at an informal settlement for internally displaced people (IDPs) in Kabul. IDPs and returning refugees often struggle to get their children into school as they try to settle into a new location, often having endured trauma and loss of possessions and livelihood through flight or deportation.

Children peek through a gate at an informal settlement for internally displaced people in Kabul, Afghanistan. The country has well over a million internally displaced people, with displacements ongoing. Displaced families often face insurmountable barriers in obtaining the documentation they need to get their children into school in their new location.

“We are still burning in the flames of war, which prevents both boys and girls from going to school,” an official from the human rights commission told me.

This is painfully true, but so many girls we met fought so hard to study. Zarifa, 17, went to a class of 30 to 35 girls in her Kabul neighborhood set up by an international organization, then transferred to a government school. She said many of her classmates drifted away. “Very few stayed,” Zarifa said. “Some married, some families didn’t allow them to continue, some had security problems.”

Students at a community-based education program in Kabul, Afghanistan. These programs are often an Afghan girl’s only chance at education and provide a temporary solution to some of the systemic barriers to girls’ education, including long distances and insecurity on the way to school, and the lack of female teachers.

The director of a community-based education program observes students. These programs—often referred to as “classes” rather than schools, as they are often based in homes—frequently consist of a single class of 25 or 30 students. They are designed to provide access to education in communities where there is no nearby school.

A class at a community-based education program in Kabul. Community-based education programs are funded through and operated by nongovernmental organizations with the expectation that the government provides oversight.