(Amsterdam) – The International Criminal Court (ICC) should prioritize victims’ views and wishes when it comes to choosing lawyers to represent them in the courtroom, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

The 60-page report, “Who Will Stand for Us? Victims’ Legal Representation at the ICC in the Ongwen Case and Beyond,” compares the way victims’ lawyers were selected in one ongoing trial to broader trends in court practice. At the ICC, victims have a right to participate in trials and are represented at trial through lawyers. The court’s system of victim participation, a key innovation in international criminal justice, creates a critical link between communities affected by atrocities and the courtroom. But Human Rights Watch found that ICC practice is falling short of ensuring that the victims’ views are adequately considered in decisions about whether and how to organize victims’ legal representation.

“The fact that victims can participate in ICC trials can help ensure they feel that justice has been done,” said Michael Adams, Columbia Law School public interest and government postgraduate fellow in the international justice program at Human Rights Watch. “But ICC officials need to reexamine how best to support victims when it comes to deciding who will stand for them in court.”

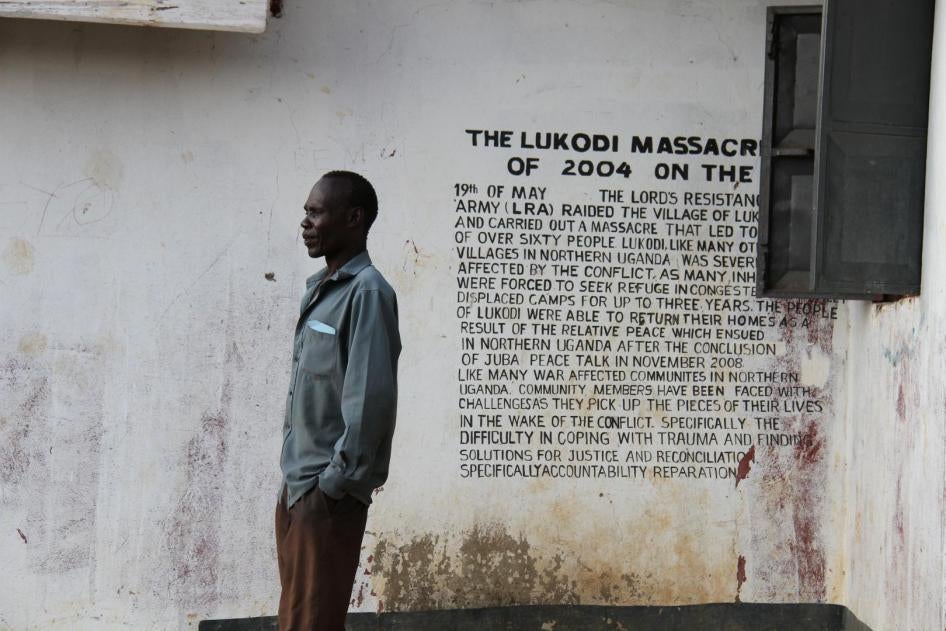

Human Rights Watch interviewed members of affected communities, representatives of nongovernmental organizations, and ICC staff, and reviewed court rulings including the decisions surrounding the choice of legal counsel in the pending case of Dominic Ongwen. Ongwen is a former commander in the Lord’s Resistance Army, a Ugandan rebel group, who was transferred to the ICC in January 2015. Two teams of lawyers are representing 4,107 victim participants in the trial on 70 charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity, which began in December 2016.

The court’s rules provide victims with a right to choose counsel, but judges can ask victims to choose a “common legal representative” – one lawyer to represent a group of victims. Where victims are unable to choose, the court can directly appoint such a representative.

In a controversial November 2015 decision, a pretrial chamber charged with handling the Ongwen case sidelined a team of private lawyers who had been appointed by some victims in northern Uganda. The chamber instead appointed a team headed by the court’s principal counsel for victims as the common legal representative, citing budget concerns and a lack of transparency in selecting the private lawyers. But it did not address the community’s motivations for selecting the private lawyers. While the court’s decision allowed the private lawyers to continue representing victims, those who chose these lawyers were left without access to legal aid for a year because the court ruled only counsel appointed by the court was eligible for support.

Judges in other recent ICC cases have appointed a common legal representative on the basis of very limited consultation with victims. A 2011 policy aimed at ensuring effective representation, along with saving time and money, seems to be at least one reason victims’ views have been given less weight in making the selection.

“The ICC’s rules may not give victims an absolute right to counsel of their choice, but they do protect that choice to a significant degree,” Adams said. “The court needs better policies to more clearly justify when it steps in to take away that choice.”

ICC member countries have put significant pressure on the court to hold down its budget, and have pressed the court to shorten the length of proceedings. This pressure appears to be a factor in how the court has designed its processes and policies on victims’ legal representation, and in judges’ decisions about common legal representation. The court is currently reviewing its legal aid policy, including for victims.

The court’s judges and its registry should put in place clear policies to ensure that legal representation decisions promote victims’ choices, Human Rights Watch said. The court should develop criteria for when it will provide support to victims to choose counsel and when, as a last resort, it will make that decision for victims. The court should use its local offices to ensure that ICC decision makers have the information they need about the concerns of victims and affected communities. ICC member countries should make sure that the court has the resources it needs to implement these policies.

“Tight budgets at the ICC are forcing decisions that undermine the court’s connection with victims and risk weakening the court’s legitimacy,” Adams said. “The court and states parties should ensure sufficient resources to support on-the-ground engagement in communities and legal aid for victims.”