Summary

It is important that I have a lawyer. It is important because whenever he comes, we will continue telling him what happened to us… I want our lawyer to stand for us in the courtroom. If it is possible, Ongwen should be convicted, and we should have everlasting peace.

—Community member, Abok Sub-County, Uganda, January 21, 2017

Ongwen as the accused has a lawyer, we who suffered should have a lawyer. It is important for us to also have a lawyer who will stand for us.

—Community member, Bungatira Sub-County, Uganda, January 17, 2017

|

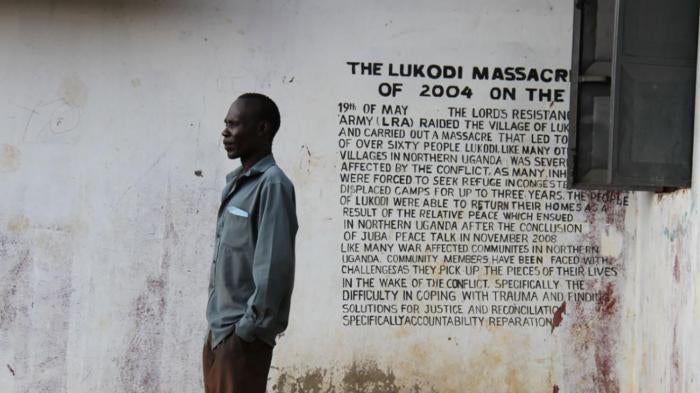

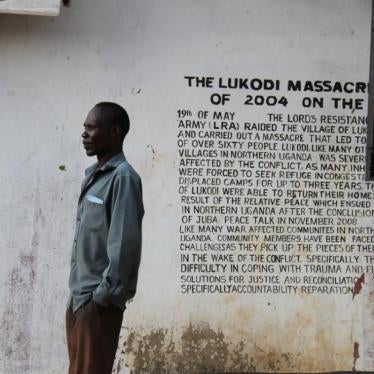

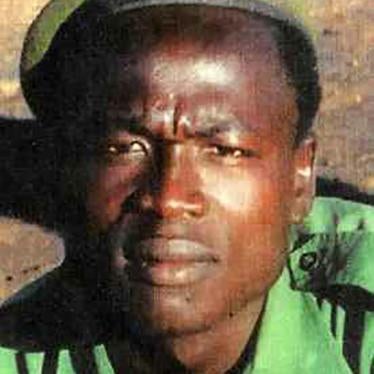

The Ongwen Case On December 6, 2016, the trial began for former Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) commander, Dominic Ongwen, for 70 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity in the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague. The LRA, a Ugandan rebel group led by Joseph Kony, originated in 1987 in northern Uganda among ethnic Acholi communities. The Acholi suffered serious abuses at the hands of successive governments in the turbulent 1970s and 1980s, and the campaign against the Ugandan government initially had some popular backing. But support waned in the early 1990s as the LRA became increasingly violent against civilians, including fellow Acholi. The group abducted and killed thousands of civilians in northern Uganda and mutilated many by cutting off their lips, ears, noses, hands, and feet. Brutality against children was particularly severe; Ongwen himself was abducted by the LRA. The impact of his abduction on his mental capacity has become a significant issue at his trial. The ICC issued an arrest warrant for Ongwen in 2005, although nearly a decade passed before he was in custody and transferred to the ICC in January 2015. The war crimes and crimes against humanity charges Ongwen now faces—including murder, torture, enslavement, and pillaging—stem from LRA attacks he is said to have commanded as an adult against four internally displaced persons (IDP) camps—Pajule (October 2003), Odek (April 2004), Lukodi (May 2004), and Abok (June 2004)—as well as other crimes committed in these and other communities. These crimes include the conscription and use of children under the age of 15 in hostilities; rape, sexual slavery, and forced marriage of abducted women and girls; and persecution.[1] Initially, only people from Lukodi could apply to participate as victims in Ongwen’s trial because charges in the original arrest warrant were limited in geographic scope. Additional charges were subsequently brought in respect of Pajule, Odek, and Abok, as well as the other crimes described above. Following a January 2016 confirmation of charges hearing, on March 23, 2016, 70 charges were confirmed against Ongwen. Two teams of lawyers represent, between them, 4,107 victims in the trial. Of these victim participants, 2,605 are represented by two independently retained or “external” counsels, Joseph Akwenyu Manoba and Francisco Cox, and 1,502 victims are represented by Paolina Massidda, the principal counsel of the ICC’s Office of Public Counsel for Victims with the assistance of a Ugandan field counsel. |

Victim participation in proceedings before the International Criminal Court (ICC) is a central innovation in international justice: in addition to potentially being witnesses called by a party or the court, victims of crimes tried before the ICC may stand before the court as participants in their own right.

This right of participation is not absolute. But it can nonetheless provide a key bridge between victims and affected communities and ICC proceedings by helping to ensure that justice is not only done, but seen to be done by those impacted by the crimes being prosecuted by the court. In doing so, it has the potential to enhance the court’s legitimacy by serving victims meaningfully.

Few victims will participate in person in ICC proceedings; they participate in its trials through legal representatives.

Victims have a right under court rules to choose a lawyer. That right is not absolute—the court’s judges, for example, can ask victims to select a “common legal representative” (CLR) with the help of its Registry and, if they are unable to do so, the judges may ask the Registry to choose one for them. The Registry also has a general mandate to support victims in organizing their legal representation. These provisions theoretically give the court considerable scope to ensure that victims are informed, respected, and enabled in their choice of legal representation.

In practice, however, budgetary pressures from ICC member countries and growing caseloads mean that Chambers have increasingly given weight to cost and efficiency implications when making decisions about victims’ legal representation. Such implications are legitimate. But they have meant that Chambers have appeared to treat victims’ views on their legal representation as a relevant, but not a determinative or predominant, consideration.

This report takes a closer look at these issues through the lens of the ICC trial of Dominic Ongwen, a former child soldier-turned commander in the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). He is charged with 70 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in attacks on internally displaced persons (IDP) camps in northern Uganda in 2003-2004—Abok, Lukodi, Odek, and Pajule—as well as sexual and gender-based crimes, persecution, and recruiting child soldiers.

Two teams of counsel are representing 4,107 victims at trial.

Based on court documents and policies, interviews with Ugandan and international civil society representatives, journalists, ICC officials, victims participating in Ongwen’s trial, and members of their leadership and organizing groups in their communities, this report considers how and why victims made choices about legal representation and the role the ICC played in facilitating—and at times undermining—those choices.

Drawing on the case, the report makes recommendations for the ICC’s future practice, designed to point towards a new way for the ICC to approach victims’ legal representation. This new approach should reflect a shared vision between Chambers and the Registry that prioritizes support to victims in making their own choices about representation.

Key Recommendations

To the Presidency and Chambers

- Recommend, in the Chambers Practice Manual, the use of a sequential approach to rule 90 as best practice for addressing victims’ legal representation.

- Amend, in close consultation with the Registry, the Chambers Practice Manual to set out the steps the Chamber and the Registry will take under rule 90, including the criteria to be used by a Chamber to determine whether it is necessary to move from victims’ free choice of counsel under rule 90(1) to victims’ choice of a common legal representative under 90(2), and, as a last resort, to a court-appointed common legal representative under 90(3).

To Chambers

- Consider whether developments in a case require new timelines to be set to facilitate victim participation and legal representation.

- Incorporate budgetary rationales more transparently into the reasoning process around victims’ legal representation.

- Develop an interpretation of rule 90(5) that is realistic about the role legal aid plays in enabling choices under rule 90(1).

To the Chambers and Registry

- In tandem with the development of criteria to be set out in the Chambers Practice Manual, develop a policy to guide the collection of information, including consultation with victims, to ensure an accurate picture informs the application of criteria in decision making about victims’ legal representation.

To the Assembly of States Parties

- Adequately fund outreach and victim participation activities, including the allocation of dedicated resources to prepare victims to choose legal representatives.

- Ensure funding is provided for legal aid, including support for victims’ choices of legal representatives under rule 90(1).

Methodology

This report is based on in-person and telephone interviews and email correspondence with individuals in Belfast, The Hague, Gulu, Omoro, Oyam, and Pader districts of northern Uganda, Kampala, and New York City between August 2016 and March 2017.

Human Rights Watch chose these locations because they are relevant to the trial of Dominic Ongwen before the International Criminal Court (ICC) as places where victims, interested civil society organizations, or academic experts were present. The ICC is headquartered in The Hague. In particular, communities near to the former internally displaced persons camps in Abok, Lukodi, Odek, and Pajule in northern Uganda were chosen because these are the primary locations in which the crimes alleged against Ongwen in the ICC case are said to have taken place.

Human Rights Watch conducted telephone and in-person interviews with 81 individuals.

In northern Uganda, interviews were conducted with a total of 40 individuals who told us they were victims of abuses attributed to Ongwen, involved in victims’ associations or serving as a link between the ICC’s activities and the community, or victim participants in the Ongwen trial. Of these, 27 individuals were interviewed individually in locations in or near to Lukodi, Pajule, and Abok; one group interview was conducted in Odek.

Present at these interviews were one or more Human Rights Watch researchers, an interpreter as needed, and the interviewee(s). Individual interviews generally lasted for about an hour, and group interviews lasted about two hours. Some of these interviews were conducted in the interviewee’s home, and other interviews were conducted in a central location to which interviewees travelled. In footnote citations, we have referred to the locations of interviews by the name of the sub-county. In the text, we have often used Abok, Lukodi, Odek, and Pajule to refer generally to the broader communities which were displaced into the camps at these locations.

The members of the victims’ associations, who were identified to us primarily through a local civil society organization, also assisted us in organizing individual interviews, but were not present during them. Consistent with Human Rights Watch practice, no one was paid for interviews, but some individuals were reimbursed costs incurred to travel to meet with us. Members of victims’ associations who assisted in organizing the interviews were also paid for their time.

We did not seek to verify the identity of these interviewees as individuals recognized by the court as victim participants in the Ongwen case. Victim participants in that case have requested that their identity be kept confidential in court proceedings. Rather, Human Rights Watch relied on members of victims’ leadership groups or community mobilizers to identify victim participants and asked those interviewed whether they had applied to participate. Of the 27 people interviewed individually, 24 indicated they applied to participate.

Given their limited number, our interviews in these communities are not intended to be a representative sample of victims’ views, or provide an authoritative account of victims’ understanding about their legal representation in the Ongwen trial. The purpose of these interviews was to give the interviewees an opportunity to explain, in their own words, how they had chosen a legal representative and whether they, as individuals, felt they had exercised a genuine choice. Human Rights Watch researchers did not ask interviewees about the nature of the alleged crimes committed against them as it was not material to the report and Human Rights Watch sought to avoid the risk of re-traumatization. In some cases, however, individuals volunteered this information.

We also did not seek to evaluate the quality of legal representation provided by counsel. The victims Human Rights Watch spoke to volunteered that they were generally happy with their legal representation. Indeed, some victims did not distinguish between the two teams.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed by telephone or in person several ICC staff members (often in group settings), representatives of 10 civil society organizations, 2 journalists, and 2 international or transitional justice experts with experience working in northern Uganda.

Almost all the individuals that we interviewed did not wish to be cited by name, including, in particular, those who were concerned to keep their status as victim participants confidential. We have used generic terms throughout the report to respect their privacy.

Victims’ Legal Representation Before the ICC

The victim participation framework established by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) is a “milestone in international criminal justice” which is “part of a consistent pattern of evolution of international law… which recognizes victims as actors and not only passive subjects of the law, and grants them specific rights.”[2]

At the ICC, victims are permitted to participate in criminal proceedings in their own right, that is, to make their views and concerns known to the judges on matters that concern them, rather than be involved simply as witnesses. This right is provided to victims under Article 68(3) of the Rome Statute.

Aware that “no such allowance [regarding victim participation] was made” at previous international criminal tribunals, Antonio Cassese, the first president of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, argued that the ICC’s system of victim participation recognizes that the victims of modern atrocities are “central to the notion of international criminal justice.”[3]

The framework of victim participation is key to the ICC’s impact in affected communities, which, together with victims, are among the chief stakeholders in the court’s work. Although only a narrow subset of victims in a given situation are likely to be recognized as victim participants, the ICC is effectively recognizing that the crimes alleged have impacted the victims when they are permitted to participate in its proceedings, incorporating their experiences and perspectives into the trial.

Victim participation creates a link between The Hague and the victims and, in doing so, hopes to make the proceedings more meaningful and relevant to them. It has the potential to be a significant factor in ensuring that justice is not only done, but seen to be done, by the victims. Ideally, contributions by victim participants to the trial, if properly structured, will also have forensic value.[4]

“Participation” in this context does not mean that victims have a role equivalent to the prosecution or the defense. Rather, they participate in a trial by presenting their “views and concerns” on particular issues at various stages of proceedings. For example, victim participants may be allowed to make opening and closing statements at the trial, or provide evidence that assists the court to determine whether the accused is guilty.[5]

Article 68(3), the Rome Statute provision governing the general right of victim participation, grants the court’s judges considerable discretion to decide when and how victims participate to prevent prejudicing the rights of the accused.[6] Although the ICC’s responsibility to make participation as meaningful as possible does not displace other priorities, such as expeditious proceedings and the rights of the accused, it is not a responsibility that can be ignored without risking the court’s legitimacy.

Participation through Legal Representatives

Victims largely participate in proceedings through their legal representatives. This in turn means that “[t]he quality of the legal representation victims receive is essential to their meaningful and effective participation in ICC proceedings.”[7]

Victims’ legal representatives must have a range of competencies, including the ability to:

- Effectively engage and consult with victims in the field to understand their views and concerns. A community mobilizer said: “The court is going to win it because we have told them the truth … [the lawyers] said what we told them.”[8]

- Play a dual role in court by contributing to the proceedings through communicating the views and concerns of victims, and providing victims with a point of reference and familiarity in an otherwise unfamiliar environment. As one victim said: “I saw [Ongwen’s lawyer], I saw [one of the victims’ lawyers], I even saw Ongwen. When I saw our lawyer, I was very happy.”[9]

The ICC’s court-wide strategy on victims identifies “effective legal representation” as an element of ensuring the right of victims to fully exercise their rights of participation.[10] ICC court decisions have repeatedly articulated the need to “ensure that the participation of victims, through their legal representative, is as meaningful as possible, as opposed to purely symbolic.”[11]

Several court actors share overlapping responsibilities for achieving this objective (see chart).

|

ICC Registry |

||

|

Before ReVision |

Relevant Roles |

After ReVision (in situations with field offices) |

|

Outreach Unit of the Press Information and Documentation Section |

|

Field Offices* (*in coordination with the Outreach Unit and VPRS) |

|

Victims Participation and Reparation Section (VPRS) |

|

|

|

Office of Public Counsel for Victims |

||

|

||

Organizing Legal Representation

The organization of victims’ legal representation is addressed in the court’s Rule of Procedure and Evidence 90.

|

RULE 90 Legal representatives of victims

|

Rule 90(1) establishes a protection for victims’ choice of counsel.

Victims’ choice matters because it can be a way for the victims represented to develop confidence that the counsel who stands for them before the court will represent their views, in turn building confidence in the court process itself.

One interviewee said:

It’s important to choose a lawyer because he will represent my views on my behalf. The meeting [between the community and lawyers seeking to act as the legal representative] helped with the choice. It helped because the government didn’t interfere with it, and I trusted the lawyer. It was of my own free will.[12]

Another interviewee said:

We decided to choose [the lawyer] because he was close to us… We sat at a meeting to decide this. So many people were there. Names of lawyers were brought in a book. We heard [the lawyer] and chose him… I saw the trial on the screening… Saw [the lawyer] there. I was pleased to see him deliberate in the court because he is a good man.[13]

Choice is by no means the only or even the most important aspect of effective representation. As discussed in Sections II and IV, the people we spoke to who had participated in the decisions about counsel did so on a spectrum, with some accepting choices made by community leaders. Many interviewees spoke to us of the importance they also attached to seeing their lawyers represent their views during screenings of court proceedings.

But the ICC needs to take every opportunity it can get to deepen its local impact, including its legitimacy. The system of victim participation should empower victims in the legal process, and supporting and understanding victim choices when it comes to who will stand for them in court can be an important starting point.

However, numerous Chambers have provided that the right to choose a legal counsel in rule 90(1) is not absolute. Rather, it is qualified by rule 90(2) and (3), which describe how “common legal representation” (CLR)—the representation of victims collectively by a lawyer or team of lawyers—should be arranged.

Common legal representation requires victims to join into “de facto compelled group representation,”[14] subject to any applicable rights of review.[15] The CLR framework is “the primary procedural mechanism for reconciling the conflicting requirements of having fair and expeditious proceedings, whilst at the same time ensuring meaningful participation by potentially thousands of victims, all within the bounds of what is practically possible.”[16] Victims who do not like the CLR appointed by the court may of course opt out of the case, but this is a “drastic decision that leaves the victim with no alternative methods of participation.”[17]

Under rule 90(2), the court may require that CLR be organized where “there are a number of victims” to “ensure the effectiveness of proceedings.”

Rule 90 sets out two ways of organizing CLR:

- Under rule 90(2), the Chamber may “request” that the victims “choose a [CLR]” with the assistance of the Registry;

- Under rule 90(3), if “the victims are unable to choose a [CLR] within a time limit that the Chamber may decide, the Chamber may request the Registrar to choose” a CLR.

While rules 90(2)-(3) qualify the choice of counsel protected in rule 90(1), both the Rules and the corresponding court regulations reflect a concern that the appointment of counsel remains informed by the choice of victims or by their interests.

Regulation of the Court 79 sets down the process for the Registry’s choice of CLR under rule 90(3). It provides that the views of victims “should” be considered and allows victims to request that the Chamber review a decision by the Registrar made under rule 90(3).

In contrast, a Chamber itself may use Regulation 80 to appoint a victims’ legal representative where “the interests of justice so require” and “following consultation with the Registrar and, when appropriate, after hearing from the victim or victims concerned.” The decision is not reviewable. Regulation 80’s flexibility reflects these differences in language and that it is part of the Chamber’s suite of “inherent and express powers… to take all measures necessary if the interests of justice so require.”[18]

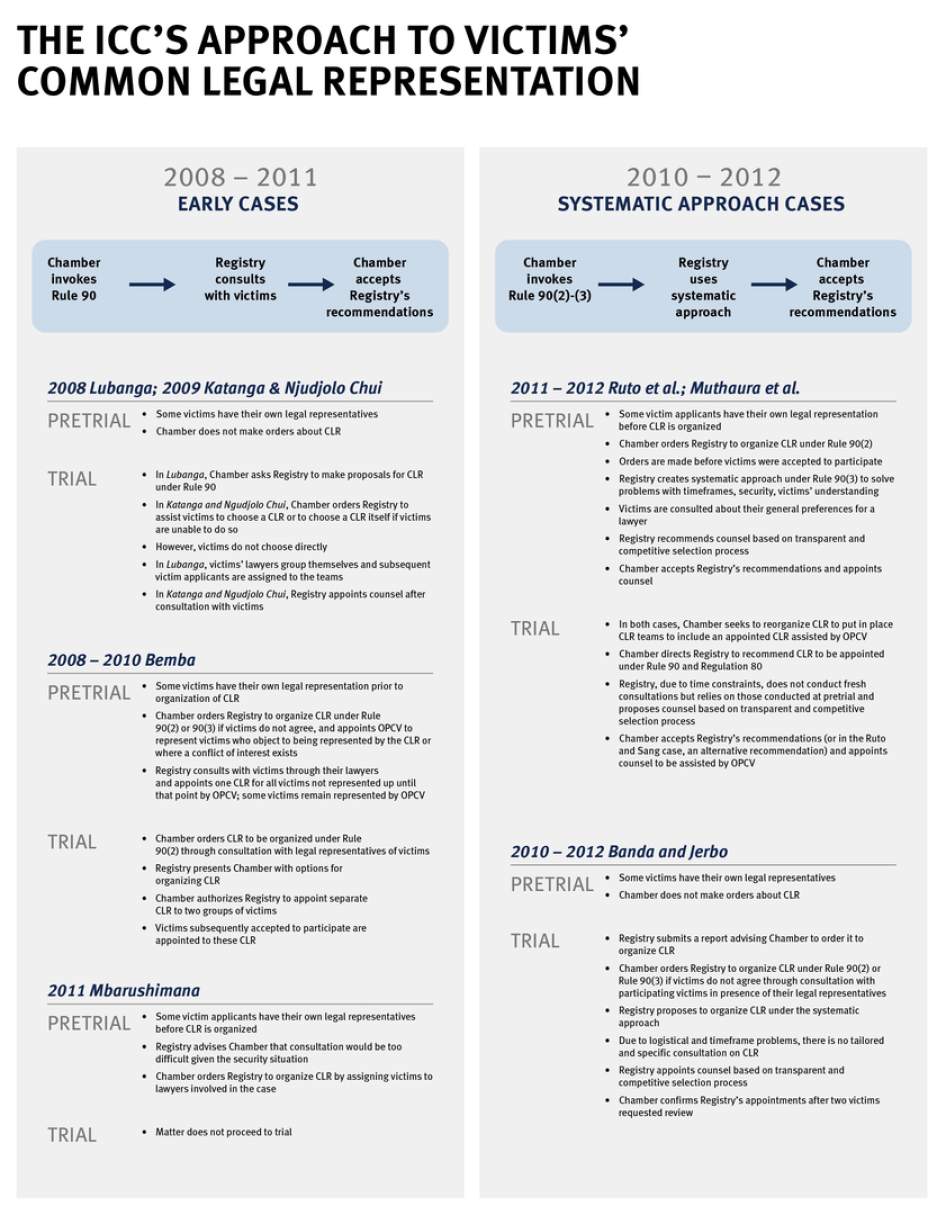

Trends in the Organization of Common Legal Representation

In almost all cases, the ICC has intervened in victims’ legal representation by appointing lawyers as CLRs.[19] As the graphic below illustrates, in so doing, the court has historically experimented with several different approaches to the organization of CLR under rule 90(2) and (3). Despite considerable variation, the Chambers and the Registry have approached the organization of CLR across the court’s cases in roughly three stages.

- First, the Chamber will issue an order, setting out the basis for the intervention into victims’ choice and directing the Registry, in general terms, as to how it should proceed in its consultations and other interactions with victims. Sometimes, but not always, the Chamber will direct the Registry to act under rule 90(2) or (3).

- Second, the Registry will then engage with victims, with the intention of assisting them in choosing a CLR under rule 90(2) or, if rule 90(3) is invoked, to assist the Registry in deciding who is an eligible candidate for CLR.

- Third, at the end of the process, the Registry will report to the Chamber on its activities and, if acting under rule 90(3), will generally—but not always— recommend that the Chamber approve a CLR.

Some broad trends may be observed from the court’s practice prior to the Ongwen case.

The most significant trend is the move away from a “sequential approach” to rule 90(2) and (3). The “sequential approach,” a term coined by REDRESS, treats sub-rules (2) and (3) as providing a structured process of decision making that allows victims to attempt to organize their own CLR before that control is relinquished to the Registry and the Chamber, should victims be unable to agree.[20] The Chamber ordered the Registry to undertake the sequential approach, with varying degrees of fidelity and victim involvement, in the Lubanga, Katanga and Ngudjolo Chui, Bemba, and Banda and Jerbo cases. The organization of legal representation in these cases took place between 2008 and 2011.

However, after this initial batch of cases, the sequential approach to rule 90 fell out of fashion. This appears to be because the Registry began to view the degree of consultation required to assist victims in choosing their own legal representation as a serious burden, complicated by logistical and security reasons.[21]

Around the time of the Kenya cases and the Banda and Jerbo case in 2011, the Registry proposed a new “systematic approach” to organizing CLR with three components:

- “early action on CLR”

- “meaningful consultation with victims” and

- “an open transparent and objective selection process.”[22]

The Registry was concerned that its previous approach, in which CLR was organized relatively late in the pre-trial process and made use of the existing arrangements made between victims and counsel was encouraging “fishing,” that is, the solicitation of clients by counsel in order to improve the odds they would eventually be appointed CLR.[23]

The Registry adopted six criteria to guide its identification of a candidate that could be proposed to the Chamber under rule 90(3).[24]

The adoption of this new systematic approach emphasized the power of the Registry and the Chamber to oversee CLR, and marked a transition towards using the top-down approach set out in rule 90(3) by default. After the systematic approach was introduced by the Kenya cases, the Chamber has not invoked rule 90(2) as a specific and primary basis for organizing CLR. In pretrial proceedings in Gbagbo and Ntaganda, in 2012 and 2013, the court organized CLR before or at the time that victims were admitted to participate in the case.[25] In these cases, the registry consulted victim applicants regarding the qualities they would want in a lawyer.

As a corollary to the systematic approach, Chambers have increasingly used Regulation 80 of the Regulations of the Court to appoint members of the court’s Office of Public Counsel for Victims (OPCV) as CLR. Regulation 80(1), in its present iteration, permits the Chamber to appoint a legal representative for victims in the interests of justice. Regulation 80 has been used in this way in the Gbagbo, Ntaganda, and Ongwen cases,[26] as well as during the admissibility challenges to the Gaddafi and Al-Senussi cases.[27] Before that time, it was also used to appoint OPCV counsel as assistants to teams of CLRs,[28] and, in the context of cases arising out of the Darfur situation, to appoint an external counsel to represent unrepresented victims until they obtained legal counsel of their own.[29]

Consistent with Regulation 80’s more flexible language, the Chamber has typically relied on the Registry’s reporting of victims’ views when deciding whether to exercise Regulation 80, but has not treated itself as bound to appoint the candidate the Registry recommended under rule 90(3). The Gbagbo Pretrial Chamber’s judge rejected the recommended candidate,[30] and in pretrial proceedings in Ntaganda, the Registry did not make a recommendation.

Overall then the trend for organizing CLR—apparently driven by efficiency and economy—has been away from rule 90(2) and, to some extent, 90(3), and towards Regulation 80.

In Gbagbo, for example, the Pretrial Chamber’s judge appointed a member of the OPCV as CLR under Regulation 80, to be assisted by team member based in Côte d’Ivoire and subject to any further revision at the trial stage, because:

…of the short time remaining until the scheduled date for the confirmation hearing…. this is the most appropriate and cost-effective system at this stage as it would … combine understanding of the local context with experience and expertise of proceedings before the Court, without causing undue delay in the case at hand.[31]

Similarly, in Ntaganda, the Pretrial Chamber’s judge appointed the OPCV as CLR under Regulation 80 because it was expected that the victims would rely on the ICC for legal aid (see below). The Chamber’s judge considered the decision justified considering the OPCV’s experience in the Congo and the limited scope of the confirmation of charges hearing.[32] This decision to appoint the OPCV overrode the powers of attorney submitted by some applicants in favor of six different lawyers, which the Chamber’s judge considered to be too financially onerous. At trial in both cases, the Chambers confirmed that victims were satisfied with their legal representation and retained the pretrial CLR arrangement.[33]

Use of Regulation 80 to appoint OPCV as common legal representative is the instrument the court has used for reasons of cost and efficiency.

Legal Aid and Legal Representation

Most victims cannot afford to retain their own lawyers, and need legal aid, which the ICC’s budget, funded and approved by member countries, sets aside for victims’ counsel.

As discussed below, a key issue in Ongwen is whether rule 90(5) restricts the court’s legal aid to counsel “chosen by the court” as the common legal representative:

A victim or group of victims who lack the necessary means to pay for a common legal representative chosen by the Court may receive assistance from the Registry, including, as appropriate, financial assistance.

This is not a new idea; Chambers have occasionally raised this interpretation of rule 90(5).[34] Nonetheless, historically “[i]n practice, the legal representatives of victims [have been] without exception paid for by the Court.”[35] Victims who chose their own counsel under rule 90(1) in the Lubanga, Katanga, Abu Garda, Banda and Jerbo, and Mbarushimana cases received legal aid,[36] although CLR was eventually organized in all but the Abu Garda case.

The issue of who is eligible for legal aid has become more significant as budgetary pressure on the court has mounted. A group of ICC states parties, including some of the ICC’s largest contributors, have pushed for a “zero nominal growth” court budget that would not even increase to adjust for inflation.[37]

Reductions in legal aid have often been a target. State parties have considered whether appointing OPCV members could be a more cost-effective alternative to the appointment of what are referred to as external counsel.[38] States parties have also pressed the court to increase the efficiency of proceedings, a concern often raised in tandem with concerns about cost.[39]

A proposal within the context of the ReVision, a framework for reorganizing the Registry directed at “two essential criteria: cost-effectiveness and fairness,” would have abolished the Victims Participation and Reparations Section (VPRS) and OPCV and combined their functions into a “victims’ office,” including an internal pool of lawyers from which victims’ counsel would be appointed, with the possibility to add an “ad hoc ‘external’ counsel” for each case.[40] The International Federation of Human Rights has observed this approach derived from that of the Pretrial Chambers in Gbagbo and Blé Goudé and Ntaganda.[41]

The ReVision proposal for a victim’s office, later revised to mandate external counsel as lead counsel, supported by an in-house pool of lawyers,[42] would require the judges to amend the court’s regulations and has not been implemented.

It triggered a long-standing debate about the role of OPCV versus that of external counsel in the representation of victims. Some civil society organizations with a mandate to monitor ICC performance, including Human Rights Watch as a member of the Coalition for the International Criminal Court team on legal representation, have said there are advantages to having external counsel involved in representing victims, including ensuring that victims’ legal representation is perceived as fully independent from the court.[43] This debate is not the subject of this report. It is clear, however, that budgetary constraints add pressure to court decisions regarding the organization of victims’ legal representation.

II.Informing Victims’ Choices

In the Ongwen case, the Pretrial Chamber’s judge did not implement a rule 90(2) or (3) process. Instead, motivated by several factors (see below), several victims signed powers of attorney with two counsel ahead of the January 2016 confirmation of charges hearing in the case, outside any court-organized process for choosing legal representation.

Court Activities in Lukodi

Although the ICC had sought Ongwen in relation to the attack on Lukodi since 2005, he was not in custody until he defected from the LRA, ending up in the hands of US and Ugandan forces in Central African Republic on January 6, 2015.[44] He was ultimately delivered to the ICC.

This was not the beginning of the court’s work in northern Uganda, however. The Registry gradually began conducting activities in northern Uganda over time, after the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) opened investigations in 2004. These activities included “outreach” activities, designed to improve the affected communities’ understanding and awareness of the ICC’s work and the role of victims in the court’s processes. As part of its outreach, the Registry conducted workshops with civil society organizations, the legal profession, and community leadership groups; participated in radio and television programming;[45] and, since 2007, engaged with victims across northern Uganda, including through community outreach in Lukodi.[46]

During this period, the VPRS began to accept applications for victims who wished to participate in the ICC’s investigations and activities in the northern Uganda situation as a whole, in addition to the case opened in 2005 against Joseph Kony, Ongwen, and three other senior LRA commanders. However, very few of these applicants were ultimately involved in the charges against Ongwen, and even fewer were from Lukodi, Pajule, Abok or Odek.[47]

Over time, the ICC and victims in Uganda engaged less and less. According to the Registry, this was because there had been no arrests or developments in the situation, and victims saw few prospects for reparations.[48] Lack of progress led the Registry to scale down its outreach activities.[49]

The situation changed when Ongwen was arrested, and his arrest warrant was unredacted in January 2015. The unsealed arrest warrant made clear that the charges focused entirely on Lukodi. Given the court’s caselaw, this meant only victims from Lukodi were eligible to be recognized as victim participants.

At the direction of the Pretrial Chamber’s judge in March 2015, the Registry began to intensify its work, both through general outreach and facilitating the application process for potential victim participants. [50] As a matter of general practice, the Registry discovers whether a person is eligible to participate in the case by reviewing the information they provide in “victim application forms” collected by the VPRS.

This initial collection of victim application forms in June 2015 marked a “first phase” of victim applications. During this first phase, the ICC was focused on the victims in Lukodi and, unlike the second and third phases discussed in Section IV, there were not yet two teams of lawyers involved in the case.

Role of the CORE Team

In conducting outreach and collecting victim application forms in Lukodi, the ICC benefited from the existence of a community leadership structure, known as the Community Reconciliation (CORE) Team. The structure was organized in 2010, when a local civil society organization, the Justice and Reconciliation Project (JRP), began to discuss with the people of Lukodi the idea of “community-led documentation” of the LRA attack.

During these discussions, some community leaders proposed that they meet regularly to facilitate discussions about bringing the community together, organizing to lobby for compensation for the attack, and building a memorial to the victims of the attack, leading to the creation of the CORE Team.[51]

The Lukodi CORE Team has existed in its present form since 2012. The JRP had been engaging with about 10 local community leaders, who identified others who might be interested in working on victims’ issues. A group of 25 was eventually presented to a community gathering in Lukodi, who were asked whether they accepted the group as their CORE Team.[52]

Once Ongwen was brought before the ICC in January 2015, civil society organizations introduced ICC staff to the CORE Team.[53] With the assistance of the CORE Team, outreach staff adopted a strategy of travelling parish by parish in Lukodi, going to individual villages and at times individual homes, and engaging with community members about the ICC’s work and the potential for victims to participate.[54] At these meetings, outreach staff would provide information about the court and answer questions. They provided general context about, for example, the referral of the Uganda situation to the ICC, the nature of an ICC trial, and the specifics of the Ongwen case before explaining victim participation and representation.[55]

The outreach staff’s messaging on victim participation and representation explained the distinct role that victims played in the trial, distinguishing them from witnesses and explaining that victim participation was different to the concept of reparations. The victim participation application form and the role of VPRS was explained. Outreach staff also explained the purpose of legal representation to victims, that they could not all go to The Hague, and why it was important to have legal representation. The purpose of this messaging was to lay the groundwork for the VPRS, with whose staff these messages were developed and coordinated. Outreach staff broadcast the same messages over the radio.[56]

The VPRS began to collect victim participation application forms from victims in Lukodi in July 2015, recruiting and training local university students to act as translators and assist victims to fill in the forms.[57] The VPRS also organized meetings with victim applicants in Lukodi to help them fill out applications and answer questions about the forms.[58] The VPRS consulted applicants on their preferences for legal representation, namely whether one lawyer could represent all victims participating in the case and what qualities they wanted in a lawyer.[59]

As it had for the outreach team, the CORE Team assisted the VPRS by acting as a “bridge.”[60] For example, the CORE Team would organize meetings at different villages at which the students would assist victims to fill in victim application forms and would communicate information to the victims on behalf of the VPRS.[61]

The Registry’s strategy of engaging with the local leadership on the ground and using it to access villages in Lukodi appears to have been successful. In contrast to a previous study about the level of knowledge of the court in northern Uganda among victim participants, conducted between July 2013 and February 2014,[62] people interviewed in Lukodi in January 2017 for this report had an overall good level of knowledge about the ICC’s work and the Ongwen case.

Registry staff worked exceptionally hard to communicate with communities in northern Uganda with limited resources and within the brief time frame set by the Pretrial Chamber—roughly nine months from the date the Registry was tasked with initiating activities. One civil society representative described the process as a form of “crisis management.”[63]

Concerns in Lukodi

As the ICC began to roll out its activities in Lukodi, information began to filter into the community about the progress of Ongwen’s pretrial case, raising anxieties. A CORE Team member told Human Rights Watch that the team had heard that “the defense lawyer was saying to the judges that Ongwen should be released. We thought that the defense would get Ongwen released, and the struggle would become meaningless.”[64]

The CORE Team also did not want to risk material facts being left out by the prosecution, and, moreover, felt the judges would not fully appreciate the seriousness of the attack unless victims themselves explained what happened. The CORE Team members Human Rights Watch spoke to felt that being denied the opportunity to [put victims’ views before the court] would “affect how victims feel about the court.”[65] They were equally concerned to respond to the views of some of the religious and cultural leadership in the Acholi sub-region, who had argued that Ongwen should receive amnesty, like thousands of other LRA fighters, and be released because he had been abducted as a child.[66]

The CORE Team members told Human Rights Watch that this anxiety was exacerbated because they effectively felt disconnected from the process in The Hague due to a lack of engagement with a legal representative: “Ongwen was assigned a lawyer automatically” and that “[f]rom January… OCPV was there, but there was no information reaching the victims.”[67]

This raises another driver of the leadership’s anxiety: it was unclear to them who was acting for, and responsible to, victims at this early stage. OPCV counsel had been appointed to represent certain situation victims since around February 15, 2008, as well as some case victims of the Kony case,[68] and in March 2012 was appointed as the “legal representative of all victims and victim applicants” in Uganda, “irrespective and outside of the context of any case which has arisen or may arise from that situation.”[69]

Technically, the people in Lukodi who had not yet applied to participate in the situation or the case would not have been “victim participants” or “victim applicants” and so would not have fallen within the scope of the OPCV’s responsibilities. In any event, before the case got off the ground in early 2015, the OPCV indicated that “in the absence of judicial activities, [its] presence in Uganda was not warranted and resources requested to undertake missions to meet with victims were systematically cut from the Office’s budget. Victims have been made aware of this situation several times via intermediaries and via the VPRS, which benefits from a continuous field presence in the country.”[70]

A CORE Team member spoke about the situation in the following terms:

When the government took the case to the ICC, a lawyer was assigned as victims’ lawyer. We were told about that. Paolina was her name. [This was] in 2008. This was new information. We learned that we had been assigned a lawyer. But the lawyers were not seen here. She said she couldn’t do anything, because the work had not yet started.[71]

Another member of the CORE Team told Human Rights Watch:

I wanted a lawyer who would come and get info from us to take it to the ICC for us, and always be in contact with us, someone who…would be hardworking for us… Paolina wasn’t coming and the court was doing things. We had our own thought, about who we thought would represent us well. We were worried that we couldn’t participate without the lawyer.[72]

The lack of a present and attentive representative in northern Uganda created unease. It appeared to the leadership that the case was proceeding but there was no lawyer in court representing the interests of all the victims. And while the ICC’s activities to support victim participation process commenced relatively quickly after Ongwen’s transfer, by January 2015, communities in northern Uganda had been waiting for almost 10 years for proceedings to open before the ICC.

The Uganda Victims Foundation (UVF) questioned the OPCV’s role in an amicus brief it wanted to submit in March 2015.[73] The UVF alleged in its application—rejected as premature—that over the 10-year life span of the case, the OPCV had given victims “very little communication,” and it was “duty bound to explain to the victims of the case why the proceedings had not commenced, any obstacles in the apprehension and prosecution of the suspects in the case; as well as answer any questions that the victims had regarding their status as well as the possibility of reparations.”[74]

Search for a Lawyer

Concerned about lack of representation and the possibility of Ongwen’s release, the CORE Team began to search for a lawyer while victims filled out application forms between June and October 2015.

The ICC had explained to the victims at village meetings that they had a right to choose a lawyer.[75] Additionally, while filling out the application forms, some victim applicants had realized the court was asking them about a lawyer.[76]

According to the members of the CORE Team with whom Human Rights Watch spoke, once the CORE Team realized victims could choose their own lawyer, they wanted to move ahead as they were worried that the situation was getting “out of hand,” and that Ongwen would be released and would destroy evidence or harm victims.[77] One interviewee said the leadership had expressed its anxieties to victims and had been told that “[the ICC] will give us lawyers but … would appoint the lawyer unless we chose. It was best if we chose.”[78]

The CORE Team began telling the VPRS that the Lukodi victims wanted to choose their own lawyer. In response, VPRS staff started to provide the CORE Team with names of Ugandan lawyers, including those on a “list of counsel” the ICC retains. The VPRS also reached out to international civil society organizations to broaden the list of counsel who could potentially represent the victims in Lukodi, and requested Ugandan civil society organizations, including UVF, come and speak to the community about legal representation.[79]

The VPRS gave victims information about their rights under rule 90; how rule 90 had been applied in previous cases; and the fact that legal aid might not be available to assist all victims in obtaining legal representation. These were the only actions VPRS could take without orders from the Chamber to the Registry to proceed with organizing CLR.[80]

Lawyers had also begun coming to Lukodi and speaking with the CORE Team, saying they wanted to represent the victims.[81] Once the decision was made to find a lawyer, the CORE Team began to meet with victims in the communities and facilitated meetings between lawyers and the communities. Joseph Akwenyu Manoba had initially met with and presented his credentials to the Lukodi leadership and “some victims” in September 2015 after being invited to do so by one of the CORE Team.[82] His reputation preceded him; the Lukodi CORE Team were aware of UVF and were reportedly impressed by his relationship with them. Furthermore, the CORE Team members who spoke to Human Rights Watch were convinced that the association with UVF revealed “he had the heart” to advocate on behalf of the victims.[83] The CORE Team told us that the external counsel had requested permission from them to approach groups of victims to explain his intentions and provide information.[84]

The external counsel ultimately organized three missions to meet with victims in Lukodi. At these meetings, they had “interacted” with victims about “the role of a legal representative; the right of a victim to choose counsel of their choice; the nature of victim participation in proceedings at the Court etc.”[85] Counsel reported that 858 victims had given them powers of attorney and 450 victims had selected them “through means of direct nomination in the course of completion of the participation form.”[86]

The 10 people Human Rights Watch interviewed in Lukodi provided some more detail on the way victims had been organized to select a lawyer,[87] generally variations on a common process. Typically, they described group meetings in which members of the CORE Team would organize general meetings, at which the external counsel and, at times, other lawyers, were present, and where victims would choose a lawyer.

Four interviewees attended a meeting of this kind where the external counsel was present,[88] and two more attended a meeting where people were presented with the external counsel by the CORE Team and then “accepted” him as their lawyer.[89] Five of those six people were sure they were represented by the external counsel,[90] and the other person claimed she had chosen him but was instead represented by the OPCV counsel.[91]

The remaining four interviewees had not attended meetings. Of those four, one indicated she was represented by the external counsel;[92] another, a child, said she was represented by the OPCV counsel;[93] and the other two were not sure or did not respond to questions about which lawyer represented them.[94] One of those two interviewees was simply told by the local council leader that she should “wait for the lawyer.”[95] Another told us that he had “heard from the community about the lawyer” but could not really remember how this information had been relayed.[96]

The six interviewees who had clearly attended a meeting with the external counsel indicated that it was important to them to have chosen him based on an assessment of his character. One interviewee told us that she had gone to see him speak at a general meeting at the Lukodi school and had chosen him “based on personal belief. He spoke with me and I became convinced.”[97]

Another interviewee noted that he had chosen Manoba because of the time he had taken to do a presentation. Manoba had said at that meeting that he would “stick with the community,” which the participant said, “impressed him.”[98] A member of the CORE Team, reflecting on the process in his capacity as a victim, recalled being impressed by a presentation by the external counsel team: “They seemed very truthful.”[99]

One of the important things that emerged from Human Rights Watch’s interviews with victim participants, however, is that not all appear to have been given a “choice” in the sense that alternatives were provided. As one interviewee who had attended a meeting with the external counsel explained it, “the CORE Team made a choice” that the community then readily accepted and did not appear to question.[100] For her, the “choice” was more of an endorsement or ratification of the lawyer the CORE Team presented.

This interviewee had attended a meeting where the CORE Team had said that the lawyer they had brought was “good, educated, and had taken law” and Manoba “said that he would work very hard for Lukodi.”[101] The CORE Team then told the victim participants that as a group they had the right to choose, and “if this lawyer is not doing the right thing, [the victim participants] have the right to reject him.” The interviewee expressed her trust for the CORE Team, which “had been in contact with this lawyer and the ICC, so the decision they came to was the right decision.”[102] The participant ultimately accepted Manoba as the lawyer because, “[w]hat he said was satisfactory…. If what he had spoken was not satisfactory, I think the community would not have chosen him.”[103]

Another interviewee, who had also been at a meeting where the group was presented with Manoba, said that she was glad the CORE Team had acted to bring a lawyer to meet their community:

We were not surprised, we were happy… The ICC was about to begin [and] we were just here, but without a lawyer. And Ongwen had a lawyer.[104]

She said that the idea to choose a lawyer had come about during ICC outreach activities, and that subsequently people who she believed to be ICC staff and the CORE Team had returned with one.[105]

Codifying Choice

The picture that emerges from the above account is one in which victims’ leaders, spurred by anxieties about a lack of representation in the courtroom, acted to organize victims in a remarkably participatory way to choose a team of legal representatives. This situation, and the degree of proactiveness and organization of the victims’ leadership, is entirely out of sync with the premise of the systematic approach.

Ordinarily, the systematic approach calls for early intervention into victims’ decision making, with the effect of preempting the kind of organic, community-driven approach to organizing legal representation that occurred here. When the CORE Team took matters into its own hands, the Registry, lacking authorization to conduct its now standard approach to organizing CLR under rule 90(3), and apart from consulting victims on basic preferences about legal representation, limited its role to providing information about rule 90 and giving victims information about choosing lawyers.

This is an entirely appropriate response to the situation. Where there have been no orders made by the Pretrial Chamber, there is no legal basis for the Registry to intervene in victims’ decision-making. Rule 90(1) is, at this stage, in full effect. To the extent that it is appropriate for the ICC to intervene at this point, it should be done by educating victims about the purpose of legal representation, providing information about lawyers on the ICC’s list of counsel, making clear the possibility that their choice can be displaced should the court decide to organize CLR, and communicating the limits regarding the availability of legal aid.

Moreover, it is positive that victims be allowed to organize their own legal representation. The leadership’s anxieties, even based in part on a misconception about the OPCV’s role, reflect a deeper urge to participate in the process through their legal representatives. Therefore, the leadership’s actions and the involvement of victims reflect a view that Ongwen’s trial is important for victims, which supports the ICC’s legitimacy and purpose.

There was some confusion about the power of attorney. One civil society organization representative told us that “[t]here is a need to educate victims about what constitutes a power of attorney. Victims accept what they’ve been told.”[106]

The victims Human Rights Watch interviewed generally placed a far greater importance on the process of consensus or acclamation by which the community endorsed Manoba as their lawyer. Some victims in Lukodi did not appear to understand that it was important that they sign the power of attorney, as opposed to signaling their consent in other ways to secure their lawyer-client relationship with Manoba. For example, one victim described a meeting in which Manoba made a presentation and the community accepted him via consensus. The CORE Team then filled out the collective power of attorney—what the victim described as a “form”—in accordance with the group consensus that Manoba be chosen as the victims’ lawyer.[107]

This had knock-on implications in a number of cases. Two interviewees told us that they had filled out forms for children to accept Manoba as their counsel but that the children had been assigned to the OPCV instead.[108] Another interviewee believed she had accepted Manoba as her lawyer at a meeting but was later told that she was represented by Massidda. When she asked why, she was told that there were two forms and that she had not filled out the second form. Accordingly, when the forms “went to The Hague, they sorted out people who did not fill the second form, and those people have Paolina [Massidda].”[109]

The interviewee was not concerned that she had been assigned to OPCV counsel—she had seen the OPCV counsel speak during a screening and was happy because “I knew she would speak for us.”[110] Another interviewee, who had attended a meeting with Manoba and other lawyers, said an “attendance list” was taken after the decision to choose Manoba was made that everyone signed, which he understood was “an agreement” that Manoba be the lawyer.[111]

It is concerning that the victims to whom Human Rights Watch spoke did not place particular significance on the power of attorney; however, for the few victims Human Rights Watch spoke to in Lukodi at least, they did not feel coerced or unclear as to what was happening. The four victims who told us they had filled out the “attendance list,” or had it filled out for them, did so because they wanted to affirm the choice they had made. It would be far more concerning, and inconsistent with the principles of agency, if the victims Human Rights Watch interviewed had not understood what was happening.

III. Respecting Victims’ Choices

Victims in Lukodi, animated by their own concerns, selected their lawyer in a way that was very different to the court’s practice under the systematic approach. Rather than being consultees, or a factor to be balanced in an overall calculus of decision making about CLR, victims’ leaders developed their own ad hoc approach based upon their own perceptions of the process and the need to protect their own interests.

That the victims in Lukodi were informed about their choice, and decided to exercise it, is an example of rule 90(1) working well. At least on the story Human Rights Watch heard from the CORE Team and some of the victims, the victims wanted to have confidence in the proceedings and protect their interests so they chose a lawyer. The Pretrial Chamber’s reaction, particularly with respect to the issue of legal aid, however, undercut the victims’ choices, even if its reasoning was notionally respectful of their choice.

The Pretrial Chamber’s Decision

In one of its routine reports about victim applications, in September 2015, the Registry noted that it had not received any indication that victims had already chosen counsel, and, as noted above, that it was collecting information regarding victim preferences on legal representation to assist any eventual rule 90 process. It went on to suggest, notwithstanding the possibility that the charges could still be expanded, that:

In the interests of ensuring an efficient and meaningful participation of victims during the Confirmation of Charges Hearing, the Registry would nevertheless recommend the appointment of a CLR as early as possible, and to this end, would like to indicate its availability to implement any order the Single Judge may wish to make under rule 90(2) or 90(3) of the Rules.[112]

The Registry further indicated that, once an order of this kind was given, it could conduct a transparent selection process for a CLR team, potentially including OPCV counsel.[113]

By October 2015, however, the Registry had received 89 powers of attorney from victims nominating the external counsel as legal representatives, and indicated to the Pretrial Chamber that victims were concerned to have their chosen legal representatives appointed as soon as possible.[114] The judge of the Pretrial Chamber decided that “only when being informed of which victims have validly chosen legal representatives, and which legal representatives they have chosen, can the Single Judge consider questions such as common legal representation or the need for appointment of a legal representative in the interests of justice.”[115]

The Chamber’s judge ordered the Registry to “verify and, if appropriate, acknowledge” the powers of attorney.[116] The Registry’s responding “Power of Attorney Report” verified not only the form in which the powers were received but the substance of the decisions made by victims. This included providing a summary of the team of external counsel’s credentials.[117]

ICC staff told Human Rights Watch that the Registry had become concerned that the powers of attorney had not been filled out properly, in that it appeared that some of the names had not been written correctly, and took notice of the fact that the team of external counsel had indicated that they would act pro bono on the powers of attorney.[118] The external counsel had explained that it meant they would not charge victims for representation, and intended to seek financial assistance from the court instead.[119]

The Registry’s principal means of verification was to consult with 38 victim applicants[120] about their choice of legal representative, concluding that the “vast majority” of victims had “a good level of understanding of legal representation”—that is, they could understand their legal representative’s role, and name or describe their lawyer.[121] Consistent with interviews conducted for this report, the Registry observed that community leaders had played “an important role,” having discussed “with the community the qualities and skills desired in their lawyers, and then introducing them to the [lawyers].”[122]

Ultimately, the November 2015 decision of the Pretrial Chamber judge respected that some victims had made a choice under rule 90(1), and accepted the powers of attorney for the team of external counsel on the basis that victims are “generally free to choose a legal representative” unless for “reasons of practicality” it becomes necessary to “disturb this freedom, as regulated in paragraphs 2 and 3 of the same rule.”[123] The Chamber’s judge could not identify any practical reasons that would justify disturbing the choice that some victims had made and so did not override their decision to choose the team of external counsel as their legal representatives.[124]

However, the judge rejected the team of external counsel’s eligibility to be appointed the CLR, because they had “not been selected pursuant to a transparent and competitive procedure organized by the Registry”.[125] Instead, the judge appointed the OPCV counsel using Regulation 80, with the expectation that one or more assistants based in Uganda would be added to the team (as she had done in Côte d’Ivoire in the Gbagbo and Blé Goudé case).[126] The benefit of this arrangement, in the judge’s view, was to combine the OPCV’s “knowledge and experience in the procedure before the Court … and the knowledge of the local circumstances where the participating victims reside, providing for the best possible legal representation of the participating victims, which is in the interests of justice.”[127]

The Pretrial Chamber’s decision also had important consequences for the team of external counsel’s access to legal aid. The text of rule 90(5) led the Pretrial Chamber judge to conclude that eligibility for legal aid was limited to the lawyer appointed by the court as the CLR. As the team of external counsel had not been chosen by the court to be the CLR, the victims represented by them were not entitled to legal aid.[128]

This approach was confirmed by a judge of the Ongwen Trial Chamber in two subsequent decisions, but the Registry ultimately granted the external counsel legal aid in late November 2016 under a separate provision, Regulation of Court 85(1).[129] This has deepened ambiguity as to when counsel appointed by victims are eligible to access legal aid.

Limits of the Systematic Approach

The potentially negative consequences of this decision for the court’s legitimacy are striking. The decision presented the victims who had chosen the external counsel with a choice—to obtain financial support from the court, they either had to surrender the counsel they had chosen and instead be represented by OPCV counsel, about whom, justifiably or otherwise, the community leadership had misgivings; or they had to remain with the lawyers they had chosen, and incur a financial obligation that they could not possibly meet.

It is true that the decision did not compel the victims to switch counsel, in some respects, going farther than rote recourse to the “systematic approach” may have done to respect victims’ choices. The withholding of financial support from the external counsel would still have created a strong incentive for these impoverished victims to change their lawyers.

As noted above, ultimately, victims have not been forced to switch to the OPCV counsel, given the Registry decision to provide legal aid to the legal representatives of victims. A member of the CORE Team told us that, if the victims with the team of external counsel had not received support, or had been forced to be represented by the OPCV:

[We] don’t know how this would go. People would think about the court in a way that would make us lose the court. [People would say] ‘We need our lawyer, but we were denied.’ But the perpetrator gets a lawyer. So it would not be balanced.[130]

Another said:

If the court rejected our lawyer on good grounds, after explaining it, to me, I believe in formal justice.… We could accept [OPCV counsel]. On the other hand, the court says the victims have a right to choose. I believe as an international body, they cannot abuse the rights of victims.[131]

That the Pretrial Chamber judge did not address this consideration in its reasoning would appear to be a consequence of it not having before it a crucial piece of context: victims’ views on the desirability of specific candidates for CLR, including an OPCV counsel.

It is impossible to guarantee access to such information. But while the systematic approach was not formally used by the Ongwen Chamber—despite its reference to the lack of a “transparent and competitive procedure” as one reason for declining to appoint external counsel as CLR—its influence and limits when it comes to increasing the odds that the court will have such information is apparent when compared with Ntaganda.

In Ntaganda, where Regulation 80 was als0 used to appoint OPCV counsel, the Pretrial Chamber’s judge had “due regard” to the general preferences of victim applicants as expressed by the Registry in its reporting.[132] Similarly, in Ongwen, the judge of the Pretrial Chamber did take the Registry’s reporting into account,[133] as the Registry had provided information in its reports on the victim application process about victims’ preferences, based on questions posed to applicants. It also considered the fact that the OPCV was already representing some individuals in the situation and in the Kony case who might ultimately have been accepted as participants in the Ongwen case.

That reporting or decision making, however, was not addressed to an actual situation in which the Lukodi victims were presented with a choice between OPCV counsel and alternative counsel to be the CLR. If victims had been presented with that choice, and had said nothing, the Chamber’s decision would have been on stronger ground.

The systematic approach has been criticized as not properly capturing the wishes of victims in the Ruto, Gbagbo, and Ntaganda cases as well.[134] This reinforces even more that the Chamber and the Registry need a new approach—one rooted in a shared vision for creating space for victims to exercise their own choices, and that recognizes a joint responsibility to accurately reflect the views of victims in the court’s decision making about how to support those choices, and when, as a last resort, it needs to step in to organize legal representation itself.

Budgetary Considerations

Before it was resolved, some victims in northern Uganda noted the disparity in funding for the two teams of lawyers.

One victim in Lukodi told Human Rights Watch that the OPCV team of lawyers could afford to hand out sodas to their clients, but that her representatives, the team of external counsel, could not and had told the Lukodi community that they would have to bear the costs.[135] Another victim told Human Rights Watch that the two teams of lawyers created suspicion that some victims were getting money while others were not.[136]

Two CORE Team members told Human Rights Watch that they had heard the court was not going to pay, and so they were not “surprised.” However, they were still concerned:

We had nothing to support our lawyer. Joseph said that he wanted to stand for people. Court may not pay for travel, but he wanted to stand for victims. We were supposed to pay. We are poor, and we can’t support him. Fortunately, the court reconsidered.[137]

In Ongwen, consistent with the increasing focus on the use of regulation 80 in the organization of CLR as an efficiency measure, the Pretrial Chamber’s judge found that appointing the team of external counsel as common legal representatives “would bring a disproportionate and unjustified burden to the Court’s legal aid budget.”[138] In contrast, the

Chamber’s judge noted that, under Regulation 113(2), the OPCV could be asked to act in order to reduce the costs of representing victims.[139]

The judge of the Trial Chamber reiterated concerns about efficiency. The Trial Chamber’s judge upheld the Pretrial Chamber’s approach to rule 90 because, in addition to his reading of rule 90(5)’s plain language as noted above, policy considerations required rule 90 to strike a balance between victims’ choice and ensuring “the effectiveness of the proceedings and cost containment” in a manner consistent with victim participation.[140]

The Chamber’s judge considered that reading of rule 90 to allow legal aid to be granted to external counsel would “prejudice this balance” and make the court “obligated” to provide financial assistance to any legal representative appointed by any victims’ group.”[141]

It is important to recognize that the ICC faces budgetary constraints which mean it cannot extend legal aid to victims without restrictions. But the court cannot lose sight of victims’ participatory rights. On the Chambers’ approach to rule 90(5), victims are potentially making decisions about counsel with the underlying prospect of being financially responsible for their choices, which will preclude most victims from having a choice at all.

The ICC risks losing a key pillar of its legitimacy if victims’ perspectives are set aside for budgetary reasons, or are materially reduced in significance. Indeed, interested civil society organizations have criticized this approach to legal aid for several reasons, including that cost-effectiveness alone should not guide court decision making about victims’ legal representation.[142]

A further problem is transparency: more is needed to determine whether the OPCV represents a cost saving over external counsel. There was no detailed accounting in the decision of the Pretrial Chamber judge of the relative costs, and previous court reporting on this issue noted further study was needed.[143] If the court wishes to take a policy decision to save money by granting legal aid to only one team of victims’ counsel per case, it would be more transparent to state this from the outset.

IV. Enabling Victims’ Choices

On September 18, 2015, the OTP expanded the scope of the charges to include victims of Ongwen’s alleged attacks in Pajule, Odek, and Abok, in addition to Lukodi, as well as the victims in the other “thematic categories:” victims of sexual and gender-based violence, child soldiers, and victims of persecution. This marked the beginning of the next phases of court efforts to facilitate victim participation.

Court Activities in Abok, Odek, and Pajule

The expansion in scope created substantial challenges for the Registry. The Pretrial Chamber had set a deadline of December 7, 2015 for the Registry to send completed victim applications. Before the confirmation of charges, the Registry had less than three months to roll out activities in the other communities.

In what constituted a “second phase” of victim applications, between September and December of 2015, ICC Outreach and VPRS staff extended their activities to Pajule, Odek, and Abok. Information sessions with 700 individuals were held in these three communities, and 400 were assisted to complete applications.

Unlike Lukodi, these other communities did not have a dedicated victims’ leadership structure with which the ICC could work. The CORE Team idea was only properly introduced into Odek by a civil society organization in 2015,[144] and the victims’ organizing groups in Pajule and Abok are almost entirely creations of the ICC, which helped these communities organize themselves after the expansion of the charges in September 2015.[145]

One representative of a civil society organization told Human Rights Watch that there were essentially no “victims’ groups” in these places in the sense that they were not as coordinated or organized as Lukodi.[146] The Registry’s difficulties in this regard were enhanced by the sheer geographic spread and remoteness of these communities.

Given the situation, it is unsurprising that roughly 80 percent of the 2,086 victims who applied from March-December 2015, during the first phase described in Section II and the second phase addressed in this section, were from Lukodi.[147]

A further “third phase” took place between July-September 2016 in all four communities after the confirmation of charges hearing. During this phase, ICC staff conducted five multi-day field missions in the four communities to enable more people to apply to participate in Ongwen’s trial.[148] Many more people also wished to apply to participate, but the Registry did not have time to process these applications.[149]

The bulk of victim applications processed from Adok, Obek, and Pajule thus took place between July-September 2016, after the two teams of legal representatives had been established in the case.[150] This arrangement provided necessary context for victims. The Registry incorporated this fact into their messaging, in coordination with the two teams of lawyers, although they also indicated that it was possible to choose other lawyers.[151]

Choosing Lawyers in Abok

Human Rights Watch conducted 15 interviews in Abok. It was difficult to ascertain from these interviews when victims had applied to participate and when they had made decisions regarding legal representation. Based on their description of events and recollection of dates, at least five interviewees most likely began to engage with the ICC only after the confirmation of charges, even if they could not remember exactly when they had applied or obtained a lawyer.[152]

It appears that one or more community meetings were held to make decisions about the selection of a lawyer.

Human Rights Watch was told about one large meeting of about 1,200 people at the sub-county office in 2015,[153] as well as smaller meetings at a local school and in other places. At these meetings, attendees were told about which lawyers were available and indicated who they wanted through a show of hands or a chorus of voices.[154] Attendance lists appear to have been used at these events in a similar manner to Lukodi.[155]

Overwhelmingly, the people Human Rights Watch spoke to in Abok preferred the external counsel “because he was close to us,” which appeared to refer to the fact that he was from a neighboring district and spoke the local language.[156] While these meetings were run by the community, in interviews, several held the impression that the ICC had organized the meetings and provided the list of lawyers.[157]

One interviewee described the larger meeting as a process of consensus where alternatives were given:

I listened to the qualities of the other lawyers. After presenting their names with their places of origin … the community was asked, ‘Who did you want to be your lawyer?’ We responded: ‘We want [Joseph] Akwenyu [Manoba]!’ We shouted it.[158]

As in Lukodi, the leadership appear to have been actively involved in the process of selecting counsel. One interviewee told us that a local leader had “recommended” the external counsel “because he comes from around here.”[159] Another interviewee, who had not been at a meeting, described the process in the following terms:

[The ICC] brought a lot of names…. [The decision] was based on consensus. They called a group of people. Joseph’s name was nominated, people saw there was a lot of support, so [they] went with it.[160]

Like this individual, one other interviewee also did not attend a meeting, but accepted the result: “I was convinced that what the community had chosen was the best thing. So I approved [the lawyer].”[161] Two others told us that they too had not been involved in making the decision, and did not know how the lawyer had been chosen, but were told the result.[162]

A few interviewees seemed to have made their decision based on impressions made by the ICC staff. One interviewee seemed to place importance on the external counsel’s proximity to victims because ICC staff had mentioned that quality.[163] One other assumed that the external counsel was the best choice because ICC staff had mentioned he was already involved in the trial.[164] Another interviewee said she understood the ICC staff to be recommending they choose a lawyer who spoke the local language.[165]

The overall picture that emerges is similar to Lukodi: a process of consensus-based community decision making, overseen by influential local leadership, which was respected by those who had not taken part in the decision. The difference lies in the fact that some of the victims Human Rights Watch interviewed were influenced by the ICC’s messaging and several had not attended meetings where decisions were made by consensus.

These differences speak to the importance of giving victims the time and space to become involved in the processes for choosing their lawyers; as one community leader indicated to Human Rights Watch, their impression of the ICC was that it was in a rush. Although the victims Human Right Watch interviewed were not sure when they had applied to participate, the fact that some were not able to participate in the process of consensus could be consistent with the fact that many individuals from Abok only applied to participate in the trial, therefore becoming eligible to choose a lawyer, during the third phase of victim applications in 2016.

Choosing Lawyers in Odek

Consensus does not appear to have been used in Odek, although Human Rights Watch was unable to speak with individual victims to verify the leadership group’s story. In Human Rights Watch’s discussion with members of the Odek CORE Team—set up in 2015, by JRP—they indicated that lawyers who were “men and women, Acholi and mzungu [foreigners]” had come with ICC staff to meetings, and then victims were individually interviewed and asked whether they wanted those lawyers, or another lawyer.[166]

There had been a choice between three lawyers: a man, a woman, and a “general lawyer.”[167] The choice appears to have been entirely individual; Human Rights Watch was told that victims made their choice “one-by-one,” while filling out application forms to participate, that there was no discussion as to who victims should choose, and some victims chose Manoba and others chose Massidda.[168]

Choosing Lawyers in Pajule

Individuals applying to participate from Pajule appeared not to have had a meaningful opportunity to decide who would represent them. Human Rights Watch was told by a local community leader that ICC staff had said at a December 2016 training that “there was a lawyer representing us … no one talked about choosing a lawyer.”[169] The organizing team in Pajule (“CORE Team” was not in usage) was used solely to organize meetings and appears to have had no role in decision making.[170] One civil society organization representative said that there was no presence of civil society organizations in Pajule, which made organizing victims “hard.”[171]