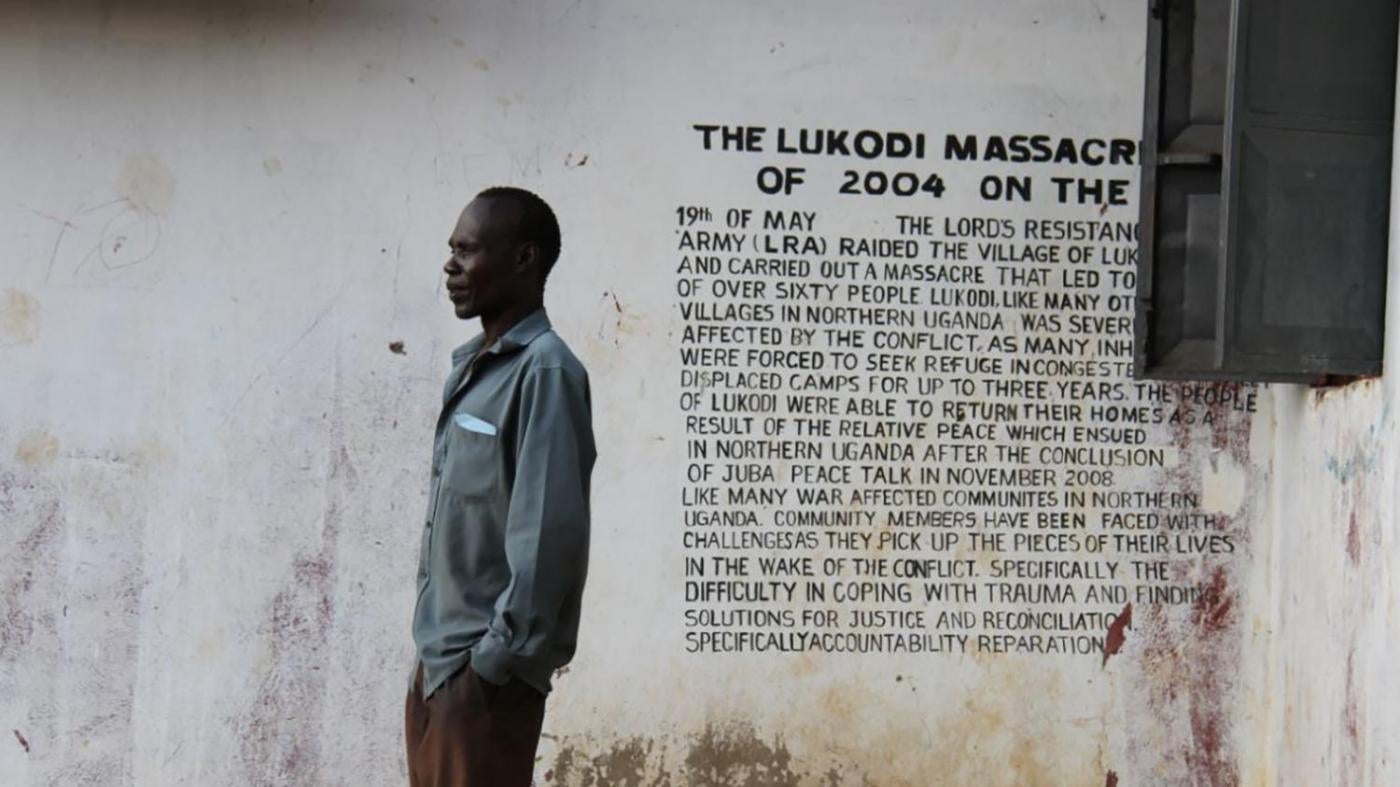

Many people in Lukodi, in northern Uganda, were killed and abducted by the brutal rebel group, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in 2004. Today, a former LRA commander, Dominic Ongwen, is on trial for these crimes and others at the International Criminal Court (ICC). Community leaders in Lukodi, concerned that victims’ views wouldn’t be fairly represented during the trial, helped people in the community choose their own lawyers to represent them at the ICC. But initially, the ICC didn’t grant the lawyers financial legal aid, undercutting that choice. Researcher Michael Adams speaks with Amy Braunschweiger about the case, and how the ICC should better support victims to choose their own lawyers – a move that would help engage victims in the court process.

Who are Ongwen’s victims?

In northern Uganda, the government moved people from their homes into camps for displaced people, ostensibly to protect them from the LRA. But the LRA began to attack the displacement camps.

The ICC’s case is focused on attacks on these camps in 2003 and 2004 in four places, Abok, Lukodi, Odek, and Pajule. The ICC prosecutor alleges they were carried out by forces under the command of Ongwen, a former child soldier. LRA fighters entered these camps, killed people, burned some of them alive, looted people’s homes, and abducted men, women, and children.

The ICC charged Ongwen with 70 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity. A total of 4,107 people who applied to be part of the case are officially “victim participants” in his ICC case, though they’re obviously only a fraction of the victims. The victims’ family members, even children, were killed, they lost their property. Some are women subjected to sexual violence and forced marriage to LRA fighters. Ongwen is accused of murder, rape, torture, destruction of property, and pillaging, among other crimes.

Who are the people who hired their own lawyer?

They are people affected by the attack on the Lukodi camp. When Ongwen was transferred to The Hague in January 2015 and the ICC arrest warrant against him was made public, it turned out that it focused on this one community – Lukodi. After the 2004 attack, people fled to another camp much farther away and after many years went back home to their land.

Leaders from Lukodi’s community, like teachers and farmers, worked with nongovernmental organizations that helped them to think about what victims needed as they tried to move forward in their lives. They created a memorial that listed the names of those killed. Eventually, the organizers became a community reconciliation team.

Lukodi’s leaders were concerned Ongwen might be released. And they felt they didn’t have a lawyer to present their perspective in the court.

Why didn’t they have a lawyer? Didn’t the ICC appoint lawyers?

The ICC has an office of lawyers tasked with assisting victims and sometimes representing them. This is an independent office, but think of them as “in-house” lawyers.

Before Ongwen’s arrest, lawyers from this office had been appointed to represent some specific victims. But apparently no one from Lukodi had applied to be recognized as a victim, as they didn’t know the case centered around them.

I think it’s fair to say that the relationship between the ICC’s in-house lawyers and the people in Lukodi was unclear. Before Ongwen’s surrender, the head of the ICC’s office of lawyers for victims said the office’s budget to make trips to Uganda kept getting cut because there was no progress in the case. They planned to make a trip in February 2015, but it was cancelled. Lukodi’s leaders had heard about an ICC lawyer for victims, but they had never met one.

What did they do?

They decided to look for a lawyer themselves. They reached out to lawyers, who came to speak with the leadership. The leadership organized very comprehensive, participatory meetings with victims of the LRA attack in Lukodi. So everyone came, and together they decided who they wanted to speak for them as their lawyers. This process was rolled out between June and October 2015, and was very organized.

Was this a problem for the ICC?

Yes and no.

If you look at the court’s cases over time, it seems like it has gotten used to organizing legal representation for victims. As a result, we don’t think the court had a policy that helped it respond effectively if victims chose their own lawyer.

In September or October 2015, people working for the ICC in Uganda knew that the people of Lukodi were selecting their own lawyer, and told the judge it would be a good time to step in and start organizing legal representation. The judge took note, and basically said, “Let’s just see what happens.” And we think it was very good that the judge just didn’t step in and take control.

But roughly a month later, the judge issued a decision, stating that while the lawyers could represent the victims who had chosen them, the court wouldn’t appoint the lawyers people in Lukodi selected to the level of “common legal representatives.” This is important because that meant their lawyers wouldn’t get financial legal aid from the court. The court made the lawyer from the ICC’s office the common legal representative in the case.

What happened next?

The lawyers continued to work for the victims even though the victims could not pay them.

It meant something to the people that a lawyer had come and seen them and asked them for permission. They felt included and that their views mattered. And that built a lot of trust. One of their lawyers is Ugandan, and he had worked with a Ugandan victims’ association and also had experience at the ICC. The other lawyer is from Chile and used to work at Human Rights Watch.

In total, by the time the trial started in December 2016, more than 2,600 victims had signed with these lawyers, both in Lukodi and other communities.

Other communities?

In September 2015, the prosecutor expanded charges to include crimes committed in Pajule, Odek, and Abok.

Because the court at first decided not to step in and organize legal representation for the people in Lukodi, it created an opportunity for these victims to choose their own lawyers, too.

But unlike in Lukodi, these new victims weren’t organized, and they didn’t have the same type of leadership. They also had little exposure to victims’ rights processes and the ICC. The experience of choosing lawyers in each of the three communities turned out to be very different. In Abok, there seem to have been some community meetings to discuss options, while in Odek, people made individual decisions. In Pajule, the few people we spoke with didn’t know much about choosing a lawyer. But we know from court records that some people there were already represented by the court lawyer. If you didn’t make a choice, you were assigned to the common legal representative.

In our view, if the ICC had more time to help educate these communities, they would have been better prepared to choose who they wanted as their lawyers. So when Ongwen’s pretrial process began in January 2016, there were officially two teams of lawyers, one supported from the court’s budget and one not.

At some point were Lukodi’s lawyers granted legal aid, I hope?

The lawyers made a couple of requests to the court to receive legal aid. Eventually, the registry – a branch of the ICC – reported that more people had joined the team of lawyers and asked the judges for their views on granting legal aid to them. And the judge now overseeing the case basically said, “No – but I leave it to you.” And the registry began paying the lawyers legal aid. This is important because now people can keep the lawyers they chose without worrying that the lawyers will run out of money to be able to come to Uganda to consult with them.

Does the ICC have the money to educate people to make this choice and to pay any lawyers they choose?

The court is facing a very tricky budget situation. Some countries that are members of the ICC don’t want to give the court more money. That’s a big part, we think, of why the court is making some of these decisions to limit the number of lawyers involved in cases. Our view is that the court shouldn’t cut victim’s rights first. Also, states need to recognize that the court can’t function at its best unless victims are included.

Why shouldn’t the ICC appoint victim’s lawyers, as it seems some victims don’t have enough information or understanding of the ICC to choose?

First, because under the court’s rules victims have a right to choose. It’s not an absolute right, but it’s there for a reason. For people from Lukodi, the choice seems to have helped give some of them confidence in what their lawyers are doing and the court’s proceedings. It’s not the only factor by any means, but choice, if it’s done well, can really promote victims’ trust in the ICC.

The ICC is often accused of not connecting as well as it should with victims and their concerns, and it should do everything it can to bring victims into the trial process. And this is another tool to do so.

What do we want from the ICC?

It seems like the court wasn’t expecting victims to pick their own lawyer, and when they did, they didn’t have a Plan B for how to respond. But we really think the court needs a new policy entirely, a new Plan A, for engaging with victims about their legal representation in a timely way.

The ICC has a policy for consulting victims when the court selects their lawyer, but as other nongovernmental groups have also pointed out, that hasn’t worked well enough, especially when it comes to making sure victims have a voice in that decision. We think there needs to be a fresh approach. We want the court’s judges and its registry to work together and to be very attentive to the needs and wishes of victims. In Lukodi, it would have meant asking “Hey, do you want to choose your own lawyers?” and then treating their answer as important. As far as we can tell, that question was never asked. And if it was, it doesn’t appear to have influenced the court’s decisions about which lawyers would be supported financially.

This interview has been edited and condensed.