Justice for Serious Crimes before National Courts

Uganda’s International Crimes Division

Summary

In recent years there has been increasing focus on making it possible for national courts to conduct trials of serious crimes that violate international law, i.e. genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. In particular, states parties to the International Criminal Court (ICC) have devoted greater attention to promoting complementarity—the principle that national courts should be the primary vehicles for prosecuting serious crimes.

This is important because international and hybrid international-national tribunals will only ever be able to prosecute a limited number of individuals—usually at the highest levels of alleged responsibility—while the fight against impunity requires a more far reaching and broader response. Moreover, national trials in countries where crimes are committed are most often best placed to ensure efforts to hold perpetrators to account have maximum resonance with local populations, and credible domestic prosecutions help ensure and build further respect for rule of law in the relevant country.

This briefing paper provides a snapshot of progress from Uganda’s complementarity-related initiative: the International Crimes Division (ICD). The ICD is a division of Uganda’s High Court with a mandate to prosecute genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, in addition to other crimes including terrorism and human trafficking.

Although the ICC opened an investigation into crimes committed in northern Uganda in 2004 and has issued arrest warrants for several leaders of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), national trials for serious crimes in Uganda could make a major contribution to securing justice for victims of Uganda’s two-decade conflict in the north between the LRA and the Ugandan army.

However, with serious legal obstacles—many predictable—already emerging during the opening stages of the ICD’s first trial, it remains to be seen whether the ICD will be able to fulfill its potential as a meaningful forum for ensuring justice for victims of this conflict. The one case now before the ICD involving serious crimes, that of LRA member Thomas Kwoyelo, is challenging the very legal framework within which the ICD operates (in particular the applicability of Uganda’s amnesty law) and its outcome will likely be decisive as to whether cases involving serious crimes committed by LRA members during the conflict can proceed.

These legal issues, as well as organizational issues in the ICD’s development to date, raise questions about how best Uganda can proceed to hold fair, effective trials of serious crimes, and may offer insights to other states facing the same task. Based on research by Human Rights Watch in Uganda in September 2011, this briefing paper sets out the ICD’s background, structure, and first prosecution. It then analyzes the ICD’s work to date, the obstacles it has encountered, and challenges both for the future work of the ICD and for national accountability efforts more broadly.

The paper highlights challenges such as whether Uganda’s Amnesty Act will ultimately bar cases against LRA members, and whether Uganda’s law implementing the ICC’s Rome Statute, which only came into force in 2010, can be used to prosecute crimes from the conflict. The paper also stresses the importance of the ICD pursuing cases involving crimes committed both by the LRA and the Ugandan armed forces, and the accused enjoying adequate support and time to meaningfully prepare a defense. Finally, the paper explores the impact of structural inadequacies within the ICD, such as frequent rotation of staff on and off the division and the lack of a witness protection and support scheme.

For the ICD to render credible justice, including addressing crimes committed by both the LRA and Ugandan army and overcoming the legal obstacles, the Ugandan government will have to provide uncompromised political support. Donors also have a critical role to play, including by funding key needs for the ICD and stressing the importance of accountability for crimes committed by both sides.

The paper is part of a wider body of work on complementarity that Human Rights Watch’s International Justice Program is developing, and researchers for the program have conducted fact-finding in 2010 and 2011 in Bosnia, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Guinea, and Kenya. Papers related to this research have been published or are anticipated.[1]

Methodology

Human Rights Watch has followed the International Crimes Division’s development since its inception in 2006, through in-person meetings, telephone discussions, and email exchanges with relevant and knowledgeable sources.

In July 2011 Human Rights Watch attended the opening of the ICD’s first trial involving serious crimes, which took place in Gulu, northern Uganda. In September 2011 Human Rights Watch conducted a week of fact-finding on the ICD that included discussions with current and former staff working with the ICD in chambers, registry, prosecution, and investigation; defense counsel; staff of nongovernmental organizations and international institutions; members of Uganda’s legal community; and officials of Uganda’s Justice, Law and Order Sector.

Several ICD officials were out of the country for training during the September 2011 research. Email exchanges between September and December 2011 and a meeting in New York in December 2011 with these and other officials working with the ICD, and with members of Uganda’s donor community, provided further information, although not all queries received replies.

Some individuals were hesitant to speak about the ICD with Human Rights Watch unless they could be assured that their identity would not be disclosed in any written product. Given that the community of individuals working with the ICD is quite small, this briefing paper does not cite names or positions of interviewees, or units in which they work, to avoid disclosing identities of those who did not want to be identified.

I. The International Crimes Division

A. Background

The northern Ugandan conflict, which raged for more than two decades, has been characterized by serious violations of human rights and humanitarian law by the LRA and the Ugandan army.[2] Following a request by the Ugandan government to the ICC Office of the Prosecutor (OTP), the OTP opened an investigation into northern Uganda in 2004. The ICC issued warrants in 2005 for three LRA leaders for war crimes and crimes against humanity, which are still outstanding.[3]

The idea for the ICD came about during peace talks to end the conflict. These talks occurred in Juba, Southern Sudan, from 2006 to 2008 between representatives of the LRA and the Ugandan government.[4] The talks produced agreements which provided that Uganda’s government would establish a “special division” to hold national trials of serious crimes.[5] While the LRA leadership never signed the talks’ final agreement, the Ugandan government committed to unilaterally implement the agreements to the extent possible.[6]

B. Legal Framework

The statutory basis of the ICD is a legal notice that Uganda’s chief justice issued in May 2011, which formally establishes the ICD and defines its operations.[7] The ICD is mandated to try genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes (referred to throughout this paper as “serious crimes”), as well as terrorism, human trafficking, piracy, and any other international crime defined in Uganda's 2010 International Criminal Court Act, 1964 Geneva Conventions Act, Penal Code Act, or any other criminal law.[8]

Uganda’s Geneva Conventions Act makes war crimes as defined under the Geneva Conventions offenses under Ugandan law,[9] and Uganda’s ICC Act makes genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity as defined under the ICC’s Rome Statute offenses under Ugandan law.[10] While war crimes under the ICC Act apply to international and internal armed conflicts, war crimes under the Geneva Conventions Act apply only to international armed conflicts. The ICC Act also incorporates modes of liability into Ugandan law that can be important to trials for serious crimes, notably command responsibility. [11]

Penalties for the crimes under the ICD’s jurisdiction range from a few years imprisonment to the death penalty.[12] ICD decisions can be appealed to Uganda’s Constitutional Court and, after that, Uganda’s Supreme Court.[13]

The ICD’s jurisdiction is not limited to particular individuals or categories of individuals, such as LRA members or members of the Ugandan army.[14] However, Uganda ’s Amnesty Act—which provides amnesty for any rebel who “renounces and abandons involvement in the war or armed rebellion”—is in effect.[15] Individuals may be barred from receiving amnesty if the minister of internal affairs obtains an “instrument” from parliament to that effect, but no such instrument has been obtained.[16]

There is no legal relationship between the ICD and the International Criminal Court.

C. ICD Structure

At least three judges sit on the ICD, appointed by Uganda’s principal judge in consultation with Uganda’s High Court chief justice.[17] The judges appointed to date bring a degree of experience in international criminal law and conducting trials, along with knowledge of the northern Uganda conflict.[18]

As regular High Court judges, ICD judges work on non-ICD cases, including outside Kampala, to help reduce Uganda’s serious backlog of High Court cases.[19] ICD judges have one paid and three unpaid staff to support their work, referred to as legal assistants, who conduct legal research and writing. The assistants are not assigned to a particular judge, but assist all ICD judges as needed.[20]

One of the ICD judges serves as a head of division, who—with the registrar’s support—is responsible for the ICD’s overall administration. The registrar handles the ICD’s daily administration.[21] At time of writing no ICD staff carried express responsibility for functions such as witness protection and support, and outreach and public information.[22]

The ICD’s prosecution function is entrusted to a unit of Uganda’s Directorate of Public Prosecutions (DPP). Between five and six prosecutors are appointed to this unit, although the number of those actively working on ICD cases fluctuates depending on workload. The unit’s prosecutors are also responsible for cases not heard by the ICD.[23]

The Criminal Investigations Department (CID) of the Ugandan Police Force is responsible for investigating crimes that may be tried before the ICD. An ICD official indicated that senior police investigators based in Kampala and in focal points around the country are attached to local police office work on ICD investigations.[24]

Both the DPP and CID said that prosecutors work far more closely with investigators in ICD investigations than in investigations involving other crimes, including travelling around the country with them.[25] Experience in international justice suggests this coordination can promote more effective investigation and prosecution.[26]

The ICC Office of the Prosecutor publicly expressed a clear commitment to assist the ICD, and the ICC prosecutor met with ICD officials in late 2010 and 2011 to provide assistance relating to possible cases.[27] An ICD official confirmed the ICC’s openness to assist the ICD to Human Rights Watch in September 2011.[28]

Uganda’s Justice, Law and Order Sector (JLOS) secretariat provides a degree of overall oversight and administration for the ICD, including interacting with Uganda’s donor community on funding matters.[29] JLOS is a government initiative that coordinates and supports various institutions that administer justice and maintain law, order, and human rights.[30]

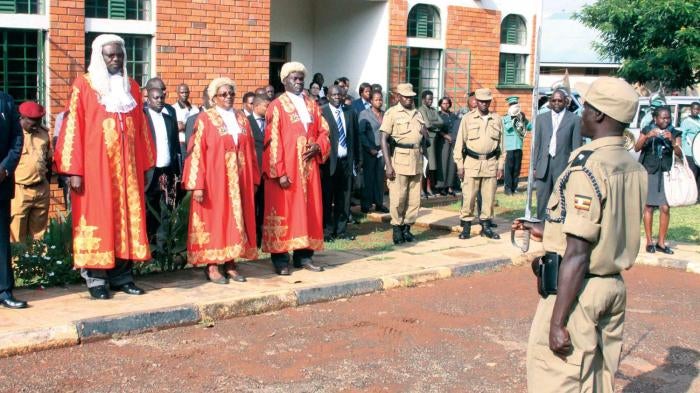

The ICD has its headquarters in Kampala, although ICD staff said the space is too small to host all staff, meetings with witnesses or among defense counsel, or securely store exhibits and archives.[31] The ICD headquarters has a courtroom, although proceedings in its only serious crimes case to date took place at the Gulu High Court, northern Uganda.[32]

D. Defense Representation

The defendant has the right to retain private counsel or receive state appointed counsel at no cost to the accused, known in Uganda as the “state brief” system. Only prisoners charged with capital offenses punishable by death or life in prison may use the system.[33]

Uganda is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which guarantees that anyone facing a criminal charge has the right to assigned legal assistance in any case where the interests of justice so require, if they cannot afford to pay.[34] The limited scope of the state brief directly undermines that right. A JLOS-commissioned needs assessment of the ICD found that the state brief is flawed in many other respects, including because judges select which advocates will represent accused in particular cases and advocates are appointed very late in the process.[35]

E. ICD Funding

The ICD is funded by the Ugandan government and international donors. This funding is provided through the regular budgeting of the justice sector and additional program support by donors.

Justice sector activities are usually funded through priorities identified in Uganda’s Strategic Investment Plans.[36] However, “transitional justice”—the area under which the ICD falls—was not identified as a priority until after the last plan was adopted, and as a result, not all ICD activities are included in the current plan.[37]

As discussed in subsequent sections, several governments—including the Danish and Irish governments—have provided project support for the ICD outside the regular budget. Others have also assisted the ICD in kind: for example, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) organized a colloquium on witness protection with Uganda’s Judicial Studies Institute and JLOS in August 2011.

II. The Start of the ICD

A. ICD Cases to Date

ICD prosecutors have sought indictments for only one accused to date relating to serious crimes, for Thomas Kwoyelo on charges of war crimes. A case involving charges of human trafficking reached preliminary hearings before the ICD, but subsequently transferred to the civil division of Uganda’s High Court.[38] The trial of 14 people charged with terrorism for the July 11, 2010 Kampala bombings began in September 2011 and is ongoing before the ICD.

Information on other possible cases involving serious crimes committed either by LRA members or the Ugandan army was not available.[39] At least one alleged LRA member, Patrick “Mission” Okello, has been in the custody of Ugandan military intelligence since March 31, 2010, although the legal basis for his ongoing detention has not been made public. Persons in detention should be promptly charged with an offense or released.[40] Plans for Okello’s release or prosecution are not known.

There is currently no overlap between ICC and ICD suspects, and the only ICD war crimes suspect, Thomas Kwoyelo, has never been subject to an arrest warrant by the ICC. At the same time, the ICC prosecutor has noted that some of the incidents covered by the indictments against Kwoyelo include incidents that have also been investigated by the ICC.[41]

B. The Case against Thomas Kwoyelo

Kwoyelo is a former LRA member who was taken into custody in Garamba National Park in northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo in March 2009, where the LRA has operated since at least 2006. Kwoyelo was first held in Uganda in the custody of military intelligence for approximately three months in an undisclosed location. Since then, he was held for a time in Gulu Prison and was later transferred to Luzira prison, a maximum security facility near Kampala.[42]

Kwoyelo applied for amnesty under Uganda’s Amnesty Act, but never received a response from Uganda’s Directorate of Public Prosecutions.

In August 2010 Kwoyelo was charged with 12 counts of violations of Uganda's 1964 Geneva Conventions Act, including the grave breaches of willful killing, taking hostages, and extensive destruction of property in the Amuru and Gulu districts of northern Uganda.[43]

Kwoyelo’s trial opened on July 11, 2011, at which the prosecution submitted an amended indictment that includes the entirety of charges under the 2010 indictment, but adds 53 alternative counts of crimes under Uganda’s penal code: murder, attempted murder, kidnapping, kidnapping with the intent to murder, robbery, and robbery using a deadly weapon.[44] The defendant registered not guilty pleas on all charges, and Kwoyelo’s defense counsel indicated that they intended to raise several preliminary objections related to the constitutionality of the case.[45]

On July 25, a second court session was held, which led to what is known as a “reference” to Uganda’s Constitutional Court for consideration of the defense objections. On August 16, the Constitutional Court heard oral submissions on the objections, which focused on whether Kwoyelo was being denied equal treatment under Uganda’s Amnesty Act by not being granted amnesty; whether Uganda’s Amnesty Act is unconstitutional and thus should not bar Kwoyelo’s case from proceeding; and whether Kwoyelo’s detention in an undisclosed location when he was first taken into custody was unconstitutional.[46]

On September 22, Uganda’s Constitutional Court issued a ruling that focused on the objections related to the Amnesty Act. The judges found that the Amnesty Act is constitutional, and that Kwoyelo’s case should be halted on the grounds that he was treated unequally under it.[47]

The Directorate of Public Prosecutions has appealed the decision to the Supreme Court, which has the final say as to whether the Kwoyelo case may proceed.[48] LOS’s secretariat has published an analysis of the decision, which highlights several problems, including that the decision “ has implications for Uganda’s national and international human rights obligations and its duty to ensure justice for victims of these violations.”[49]

If the Supreme Court affirms Uganda’s Constitutional Court ruling, and orders the Kwoyelo case to be halted, it does not mean that all serious crimes cases are barred. Cases against members of the Ugandan army would not be affected. As for LRA members, cases would depend on the non-renewal of the Amnesty Act (which should next expire in 2012) or parliament barring certain individuals from receiving amnesty. [50]

At this writing the appeal is pending and Kwoyelo continues to be imprisoned. In November Kwoyelo’s lawyers petitioned Uganda’s High Court to secure his release based on the Constitutional Court ruling; a ruling on this submission is anticipated for early 2012.

III. Lessons Learned

All criminal trials should meet key benchmarks in accordance with international standards and practice for fair, effective proceedings. These include credible, impartial, and independent investigation and prosecution; rigorous adherence in principle and in practice to international fair trial standards; and penalties that are appropriate and reflect the gravity of the crime.[51] The experience of international and hybrid war crimes courts has shown that adequate witness protection and support, and public information and outreach are also needed if cases involving serious crimes are to be effective and have resonance with the communities most affected by the crimes.[52] Below we discuss challenges for the ICD in achieving these benchmarks based on the ICD’s development to date.[53]

A. Inadequate and Problematic Legal Framework

Three domestic law and legal interpretation matters create major challenges for the ICD: Uganda’s Amnesty Act, Uganda’s ICC Act, and the availability of the death penalty as a punishment.

Amnesty Act

Uganda’s Amnesty Act provides that any rebel who “renounces and abandons involvement in the war or armed rebellion” may receive amnesty.[54] By its terms, the act appears to preclude all cases of LRA members so long as they reject rebellion, irrespective of the ICD or the crimes in which LRA members may be implicated.

Over 12,000 LRA members have received amnesty since the Amnesty Act was adopted in 2000, including more senior members than Kwoyelo, and LRA members have continued to be granted amnesty since the ICD’s inception.[55] Notably, Lt. Col. Charles Arop, the LRA’s former director of operations, surrendered to Ugandan troops in November 2009, and was granted amnesty in late 2009. Arop is accused of leading the “Christmas Massacres,” part of a series of attacks in 2008 and 2009 resulting in the deaths of at least 620 civilians and the abduction of more than 160 children in DRC.[56]

Amnesties for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity are inconsistent with international law and practice, which provide that such crimes should be prosecuted.[57] In addition, Kwoyelo’s prosecution—albeit now stalled—while other LRA members received amnesty, raises question about selectivity of cases before the ICD pursued by prosecutors.

ICC Act

Uganda’s ICC Act—which makes serious crimes and modes of liability as defined by the ICC’s Rome Statute offenses under Ugandan law—was adopted in 2010, while the majority of crimes committed in the North were committed prior to this date.[58] There is no reason under international law that the act cannot be used to prosecute crimes that predate its enactment: the principle of non-retroactivity is not violated where the conduct to be prosecuted was already a crime under international law, and the national law is not creating a new offense, but is establishing jurisdiction to try the offense. This is the case for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.[59]

Nevertheless, legal observers in Uganda believe that the Ugandan courts would not follow this interpretation and would apply the principle of non-retroactivity in Ugandan law to prohibit the use of the ICC Act to prosecute any crimes that occurred prior to 2010. Observers say prosecutors appear resistant to test this.[60]

As a result, it seems unlikely that crimes against humanity committed during the conflict will ever be charged as such and it is unclear if anyone could be pursued on the basis of command responsibility.

War crimes are being charged pursuant to Uganda’s Geneva Conventions Act, but there are questions as to whether these charges will be upheld. As discussed in the previous section, war crimes under the Geneva Conventions Act relate to international armed conflicts, and the judges have yet to make any finding as to whether the northern Uganda conflict was an international or non-international armed conflict.

Taking this into account, the prosecution has added alternative counts in Kwoyelo’s indictment for ordinary crimes under Uganda’s domestic penal code, such as murder. Prosecutions for ordinary crimes are preferable to impunity, but they can constrain the extent to which the gravity and scope of crimes, and responsibility for them can be addressed.[61] Charges of sexual and gender-based violence are also limited under Uganda’s penal code.

Death Penalty

The ICD may impose the death penalty as a sanction, although an execution has not been carried out in several years and courts have recently limited its application.[62] Human Rights Watch believes the death penalty is a cruel, inhuman punishment that should not be available as a penalty for any crime.[63] In line with the preference in international law for abolition of the death penalty, the death penalty has not been a punishment available to international and hybrid war crimes courts.

B. Importance of Pursuing Crimes by Both Sides

As noted in the previous section, the ICD’s jurisdiction is not restricted to individuals with particular affiliations, and ICD officials confirmed to Human Rights Watch that the division could try members of the Uganda Peoples’ Defence Forces (UPDF)/National Resistance Army (NRA).[64]This is an important function as domestic efforts to date to investigate crimes committed by the Ugandan army, with a view to prosecuting, have been inadequate; victims of UPDF crimes also cite fear of, and intimidation by, UPDF personnel as a barrier to pursuing cases.[65]

Investigation with a view to prosecution by the ICD of crimes committed by both the Lord’s Resistance Army and the Ugandan army are needed to promote impartiality and avoid “victor’s justice,” or the appearance thereof. The importance of such efforts is heightened by the lack of ICC action related to crimes committed by the Ugandan army. There are legitimate questions as to whether alleged crimes by members of the Ugandan army fall within the ICC’s jurisdiction, but the ICC’s relative silence about them has not helped to check a prevailing culture of impunity for crimes committed by government forces.[66]

C. Right to an Adequate Defense

Adequate resources and facilities to prepare a defense is a fundamental right of all accused under international law and Uganda’s constitution.[67] The lack of assistance to defense counsel and the limited time they have to prepare pose serious concerns to assuring fair trial rights in Kwoyelo’s case, the terrorism trial, future cases before the ICD, and criminal cases in Uganda more broadly.

While Kwoyelo secured private counsel, his defense team requested assistance from the state to support the preparation of their case, namely funds to secure two to three professional investigators, two researchers, and one consultant.[68] The JLOS secretariat asked donors to provide this support, but donors did not.[69] The JLOS secretariat is exploring other means of securing investigation and research support to the defense.[70]

The lack of investigation and research assistance raises major concerns as to whether the defense team can mount a proper defense should Kwoyelo’s trial go ahead. Support for defense representation other than state brief has special significance for the ICD: Kwoyelo secured private counsel as he waited for over a year while in prison without counsel, and he became concerned over having a state-appointed lawyer.[71] Other accused are likely to have similar concerns given that state brief defense lawyers are customarily assigned only at trial, and the Ugandan government’s own role in the northern Uganda conflict.[72]

Securing quality representation for any accused who accepts state brief is also a significant concern. Members of the legal community described remuneration for state brief as minimal, undermining the chances that adequately experienced and skilled counsel participate.[73]

Time to prepare is an additional significant concern. Although Ugandan law provides for disclosure of documents by the prosecution to the defense, there are no detailed rules governing it and in practice it occurs only once a trial is underway or about to start.[74] Prosecutors and judges also tend to be inclined against robust disclosure, often requiring multiple requests by the defense and sometimes the burden of photocopying is borne by the defense.[75] Kwoyelo’s trial was scheduled to move forward approximately one month after the defense first received substantive disclosure, which was of 77 witness statements handed over more than 2 years after Kwoyelo had been imprisoned.[76]

D. Structural Issues

Policies and procedures relating to national serious crimes trials should take account of their likely long duration, complexity, sensitivity, large volume of evidence, and novel legal issues.

As a division of Uganda’s High Court, the ICD is a fully integrated part of Uganda’s domestic system, operating according to standard judicial procedure and practice.[77] This arrangement could help to ensure the ICD has greater resonance than a more isolated initiative, and may be able to help avoid the diversion of scarce resources from the ordinary system.

At the same time, several aspects of Ugandan legal practice and procedure—which pose challenges for all criminal cases in the country—are ill-suited to serious crimes cases. These include lack of paid legal assistants for judges, frequent rotation of staff, lack of a witness protection and support scheme, and insufficient interpretation.

As discussed below in Section F, JLOS commissioned a needs assessment to identify areas where enhancements are needed for the ICD to operate effectively.[78] The Ugandan government has taken some steps to implement the recommendations, but key gaps remain.

Differences between Ordinary and Serious Crimes Cases in Uganda

Members of Uganda’s legal community estimate that criminal cases in Uganda usually involve no more than a few charges and two to twenty witnesses, with a case involving twelve witnesses described as very large. In addition, cases tend to involve at most about 30 days of trial time.[79] By contrast, Thomas Kwoyelo’s case involves more than 50 counts, the prosecution had listed over 60 witnesses it wanted to call, and the prosecution case, if it proceeds, could last several months.[80] In addition, the case raises novel legal issues, not least as Kwoyelo’s case is the first time charges are brought under Uganda’s Geneva Conventions Act.

Inadequate Legal Assistants

Legal assistants can provide important support to judges by conducting substantive research on complex legal issues arising out of proceedings and preparing and drafting legal documents. Judges in Uganda do not traditionally use legal assistants, handling legal research and writing responsibilities associated with their cases on their own.[81] One paid legal assistant is assigned to assist the ICD judges and, as needed, the registrar. Three additional assistants are also assisting the ICD judges, but they are not paid (they only received stipends for several initial months).[82]

Lack of remuneration for legal assistants may contribute to turnover and a loss of accumulated expertise to assist judges at the ICD. Donors were asked to consider supplemental funding for legal assistants for judges, but they did not fund this request.[83] A nongovernmental organization was in the process of facilitating additional research support to the ICD judges as of September 2011.[84]

Rotating Core Staff

It is common for judges, registrars, prosecutors, and investigators in Uganda to be frequently rotated on and off work relating to specific divisions.[85] One interlocutor explained that registrars tend to rotate every one to two years and judges tend to rotate every three to four years.[86] Several rationales were offered for rotation, namely that it can promote staff versatility and competence in the justice sector, allow a wider array of staff to benefit from trainings on particular initiatives, and assist in managing the small number of professionals who can play key roles across the system.[87]

However, rotations can cause a loss of developed knowledge and expertise in a specialized legal area, including because cases involving serious crimes can take an extended period to investigate and prosecute. In the two years since the ICD has been operational, two registrars and at least one of the division’s prosecutors have been rotated from the ICD to work with other divisions.[88]

Witness Protection and Support

Witnesses who testify in trials involving serious crimes—some of whom are likely to be direct victims—can face serious risks to their security and stability before, during, and after giving testimony. They may confront direct threats to the safety of their families and be in need of ongoing psychosocial support in the aftermath of testifying about deeply traumatic events.

Witness protection and support is a significant issue for the ICD: while witness protection has not been completely absent in Uganda, measures are ad hoc, informal, and limited, and there is no legal regime for witness protection (although some relevant provisions do exist, such as sanctions for attacks on witnesses). [89]

Uganda has taken some important steps to promote witness protection and support that will benefit the ICD and the justice system more widely. Uganda’s Law Reform Commission is developing a witness protection law. [90] Experienced practitioners traveled to Uganda in August 2011 for a colloquium on witness protection organized by JLOS, Uganda’s Judicial Studies Institute, and the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. [91] JLOS is also pursuing a threat assessment for ICD witnesses, funded by Irish Aid, to evaluate concrete risks for ICD witnesses, to recommend those best placed to administer witness protection (i.e., police, independent bodies), and to provide trainings on interacting with witnesses. [92]

The timing of these efforts raises concern given that some 60 witnesses are already selected to testify on behalf of the prosecution in the Kwoyelo case, should it proceed to trial. In addition, protection of defense witnesses—who were preliminarily identified—can be expected to pose particular challenges due to the likely distrust of many of these witnesses of the Ugandan police (on which informal measures traditionally rely). [93]

Witness protection and support are areas where accumulated expertise exists among international and hybrid international courts, including the ICC, from which the ICD should consider drawing.

Interpretation

Uganda has not had any formal interpretation program and many languages are spoken in the country.[94] JLOS initiated a nine-day interpreter’s training of 30 court clerks—funded by the Danish International Development Agency—several weeks before Kwoyelo’s trial opened to benefit the ICD and the justice system more broadly.[95] This reflects synergies that can occur between general justice sector reform and efforts to try serious crimes.

Kwoyelo received interpretation during his trial sessions to date, and Justice Owiny Dollo, who speaks Acholi, corrected some of the translation.[96]Concerns regarding interpretation remain, however. Interpreters did not provide interpretation of all legal discussions before the ICD.[97]In addition, interpretation was not provided at the session at the Constitutional Court challenging Uganda’s amnesty law.[98]This is a significant concern for upholding fair trial rights: interpretation of all proceedings should be available to the accused.[99]

E. Timely Public Information and Outreach

Timely public information and outreach to affected communities on national trials in local languages is important to avoid confusion and misunderstanding, all the more so in countries where the ICC is operating. Such activities are not a regular feature of most domestic justice systems, including that of Uganda. However, the experience of international and hybrid war crimes courts has shown their importance in enabling proceedings to resonate with affected communities and the public more generally.

In Uganda, organizations working with affected communities report substantial confusion and concerns regarding the ICD. These include: an incorrect belief that the ICD is a branch of the ICC, a lack of understanding as to why Kwoyelo is being prosecuted while more senior LRA commanders remain free, concerns about impunity for crimes committed by Uganda’s military, and disappointment over the lack of charges related to rape or sexual violence brought against Kwoyelo.[100]

Journalists also demonstrate gaps in understanding the ICD, and further misunderstandings in local communities. For example, around the opening of Kwoyelo’s trial, some news reports indicated that the ICC opened the trial in Gulu, and another report stated that the ICD was an “arm of the International Criminal Court.”[101]

In March 2011 the JLOS needs assessment highlighted outreach as an urgent area for follow-up.[102] After initial visits by prosecutors, judges, and investigators to communities in the north in June 2009, activities remained limited.[103] Activities increased around Kwoyelo’s trial: ICD officials conducted meetings with stakeholders and affected communities in the north around the opening in July 2011, and the ICD set up a video screen for the July 25 proceedings to allow people to watch outside the courtroom.[104] Frequently asked questions on the ICD and Kwoyelo’s trial also appeared on JLOS’s website in late September 2011.[105]

Greater outreach and public information activities are hampered by debates over who should lead on these efforts.[106] Some interlocutors assumed that JLOS should carry the primary responsibility for these activities, but there are limitations to that approach.[107] Two JLOS secretariat staff are responsible for ICD matters, but these individuals handle a range of issues beyond the ICD under a “transitional justice” portfolio. A JLOS effort to devise a “transitional justice outreach strategy” is in development, but was not finalized as of September 2011.[108]

ICD staff can be expected to have the greatest understanding of its work, and a model adopted by international and hybrid war crimes tribunals has been to have the registrar lead on public information and outreach.[109] However, there is no tradition of registrars speaking on behalf of judges and prosecutors in Uganda, and information sharing is generally restricted to comments by spokespersons.[110]

Ugandan officials explored civil society conducting outreach, and civil society have undertaken independent activities to explain the ICD’s work to affected communities.[111] Civil society can play a role in outreach on the ICD, but cannot be expected to address all issues. Especially regarding sensitive matters, such as the applicability of the Amnesty Act, Ugandan officials are better placed to conduct public information and outreach.[112]

Ultimately, the key issue is not which officials lead on outreach and public information, but that decisions are taken to designate particular officials to carry responsibility for these activities and that the officials are equipped with the resources to provide accurate information that is responsive to questions and concerns among affected communities and the public.

The ICC also can play an important role in helping to clarify the relationship between the ICD and the ICC, and the ICC has integrated some information on the ICD into its activities. In order to avoid furthering confusion, such activities should be framed with due attention to the ICC’s and ICD’s distinct roles, especially when officials involved with each participate in events together.

With regard to modes of outreach to affected communities in northern Uganda, there are actors who have accumulated experience, including the International Criminal Court, who can give detailed input on best practices.[113] These should guide the ICD’s activities, but at a minimum, regular explanation of the ICD’s operations, for example, on radio programs in Luo/Acholi that are broadcast in areas affected by the crimes, should be considered.[114]

F. Support Issues

Needs Assessment

As referenced above, Uganda’s Justice, Law and Order Sector commissioned a needs assessment of the ICD in 2010, which was undertaken by international experts.[115] The needs assessment produced a detailed report in March 2011 with numerous recommendations, including on defense representation, detention conditions, interpretation, witness protection, court reporting, records management, forensic examination, investigations, support staffing, and outreach.[116]

The assessment provides a coherent roadmap in many respects to enable the ICD to ensure fair, effective trials of serious crimes. Similar efforts could prove highly valuable for other states pursuing such trials.

While several of the report’s recommendations have been implemented, many have not. This includes a number of recommendations that were identified as urgent in the report.[117]

One important recommendation that had yet to be implemented at this writing is that all institutions affected by the assessment should meet to discuss and assign responsibility for implementing the recommendations.[118] This could help ensure a more coherent, comprehensive approach to addressing the report’s recommendations. More broadly, implementation of recommendations to address gaps related to fair, effective trials involving serious crimes should take account of the forward progress of proceedings—such as identification of witnesses—and the detention of the accused.

Trainings

Trainings are important, but should be continually assessed for their value added versus costs and drain on staff time.

Many trainings have been conducted in relation to the ICD’s work, and essentially anyone working in a professional capacity with the division has participated in some form of training. This includes training of defense counsel, investigators, prosecutors, legal assistants, and judges on issues such as conducting international legal research, investigating serious crimes, and dealing with vulnerable victims.[119]ICD officials and staff have also received personalized briefings, participated in “study tours” of international and hybrid war crimes courts, and attended other trainings outside of Uganda.[120]

Given the complexity and novelty of the war crimes cases in Uganda, training is crucial for ensuring the relevant players are as prepared as possible. However, trainings should be assessed carefully for their value added versus the drain on staff time and costs. Some staff have had numerous days and weeks of training, including multiple trips abroad, and trainings may have diminishing returns. Trainings also risk creating more confusion than understanding unless they are highly tailored to participants’ particular responsibilities and the ICD’s functioning.

Facing a similar problem, judges of the War Crimes Chamber in Bosnia established a Judicial Education Committee that reviews possible training programs for their utility and approves who may participate in training.[121] This type of approach could be useful for the ICD and other war crimes court initiatives.

Recommendations

Specific Recommendations Regarding the ICD

To Uganda’s Justice, Law and Order Sector

- Intensify efforts to secure support for defense to conduct investigations and research, and paid legal assistants for judges.

- Initiate a review of disclosure practice with a view to amending the practice to allow defense adequate time to prepare.

- Minimize rotation of key staff off the ICD.

- Expedite efforts to implement a witness protection and support scheme for the ICD.

- Ensure interpretation is provided during all criminal proceedings, including with regard to legal issues discussed at those proceedings.

- Expedite efforts to decide on persons to conduct outreach and public information for the ICD and equip them with resources to provide accurate information that responds to questions and concerns among affected communities and the general public.

To ICD Prosecutors and Investigators

- Investigate with a view to prosecuting crimes committed by both the LRA and Ugandan army on the basis of the same objective criteria.

- Pursue prosecutions of crimes against humanity and war crimes as defined by the ICC Act for crimes committed prior to 2010.

To the Ugandan Parliament

- Abolish the death penalty.

- Amend the Amnesty Act so that those accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity cannot benefit from the Act.

To Donors

- When assessing future funding of the ICD, consider prioritizing funding of legal assistants to support ICD judges, and defense counsel to conduct adequate research and investigations in Kwoyelo’s and other cases. Neither of the above have received donor funding to date and are critical to ensuring fair, effective trials.

- Urge the ICD to pursue investigation and prosecution of both LRA and UPDF crimes based on the same objective criteria.

To the International Criminal Court

- Consider ways in which the ICC can enhance the sharing of

relevant expertise with ICD officials to promote fair, effective trials

for serious crimes in Uganda, such as by increasing information exchange

on ICC outreach and public information, and witness protection and support

activities.

More General Recommendations for Governments, Intergovernmental and International Institutions, and Donors Pursuing Domestic Trials for Serious Crimes outside Uganda

- Ensure all parties to a conflict are subject to the jurisdiction of domestic initiatives to try serious crimes, and prosecutions for crimes committed by any party are pursued pursuant to the same objective criteria.

- Address obstacles to serious crimes trials based on domestic laws and legal interpretations.

- Prohibit the death penalty as a potential sanction.

- Take into account the likely length, complexity, volume of evidence, and novelty of legal issues when developing policies and procedures related to national serious crimes trials.

- Ensure timely public information and outreach on national serious crimes trials in local languages to avoid confusion and misunderstanding among affected communities, especially where the ICC operates.

- Undertake a needs assessment to identify concerns that should be addressed to ensure fair, effective trials, and take into account the progress of proceedings and the length of detention in implementing the recommendations.

- Continually assess trainings for their value added versus costs and drain on staff time.

Acknowledgments

This briefing paper was researched and written by Elise Keppler, senior counsel in the International Justice Program of Human Rights Watch. The paper was edited by Maria Burnett, senior researcher on Uganda in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, who also contributed research; Richard Dicker, director in the international Justice Program; and Param-Preet Singh, senior counsel in the International Justice Program.

Aisling Reidy, senior legal adviser, provided legal review, and Babatunde Olugboji, deputy program director, provided program review. Scout Katovich, associate for the International Justice Program, provided production assistance, and Grace Choi, Kathy Mills, Ivy Shen, and Fitzroy Hepkins prepared the paper for publication.

In addition, Rustum Nyquist, intern with the International Justice Program, provided invaluable assistance with desk research, citation, and proofreading.

[1] See Human Rights Watch, “Turning Pebbles”: Evading Accountability for Post-Election Violence in Kenya, December 2011, http://www.hrw.org/reports/2011/12/09/turning-pebbles.

[2]See, for example, Human Rights Watch, Uprooted and Forgotten: Impunity and Human Rights Abuses in Northern Uganda, vol. 17, no. 12(A), September 2005, http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/uganda0905.pdf.

[3] The ICC issued arrest warrants for five LRA leaders: Joseph Kony, Vincent Otti, Okot Odhiambo, Raska Lukwiya, and Dominic Ongwen. Lukwiya and Otti have since died. “Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court opens an Investigation into Northern Uganda,” OTP press release, ICC, ICC-OTP-20040729-65, July 29, 2004, http://www.icc-cpi.int/menus/icc/press%20and%20media/press%20releases/2004/prosecutor%20of%20the%20international%20criminal%20court%20opens%20an%20investigation%20into%20nothern%20uganda?lan=en-GB (accessed November 15, 2011); Prosecutor v. Joseph Kony, Vincent Otti, Okot Odhiambo, and Dominic Ongwen, International Criminal Court, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/05, Warrants of Arrest, July 8, 2005, http://icc-cpi.int/Menus/ICC/Situations+and+Cases/Situations/Situation+ICC+0204/ (accessed November 1, 2011).

[4]See Justice, Law and Order Sector (JLOS), “Frequently Asked Questions on the International Crimes Division of the High Court of Uganda,” undated, http://www.jlos.go.ug/uploads/ICD_FAQs.pdf (accessed October 28, 2011), p. 1; Judiciary of the Republic of Uganda, “High Court Divisions: International Crimes Division,” undated, http://www.judicature.go.ug/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=117&Itemid=154 (accessed November 1, 2011).

[5]Agreement on Accountability and Reconciliation between the Government of the Republic of Uganda and the

Lord’s Resistance Army/Movement, Juba, Sudan, June 29, 2007, paras. 4, 6; Annex to the Agreement on Accountability and Reconciliation between the Government of the Republic of Uganda and the Lord’s Resistance Army/Movement, Juba, Sudan, February 19, 2008, paras. 7, 10-14, on file with Human Rights Watch.

[6]See Judiciary of the Republic of Uganda, “High Court Divisions: International Crimes Division,” undated, http://www.judicature.go.ug/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=117&Itemid=154 (accessed November 1, 2011).

[7]The High Court (International Crimes Division) Practice Directions (“ICD Practice Directions”), Legal Notice no. 10 of 2011, Legal Notices Supplement, Uganda Gazette, no. 38, vol. CIV, May 31, 2011.

[8]ICD Practice Directions, para. 6(1).

[9]Geneva Conventions Act (Ch 363), October 16, 1964, http://www.ulii.org/ug/legis/consol_act/gca1964208/, art. 2 (accessed October 27, 2011).

[10]International Criminal Court Act (“ICC Act”), Acts Supplement No. 6, Uganda Gazette, no. 39, vol. CIII, June 25, 2010, arts. 7-9.

[11]Command responsibility allows for liability of those who were not involved in the direct commission of crimes, but were responsible for them due to their leadership positions. Ugandan courts have previously rejected applying this mode of liability, although the ruling did not specifically relate to serious crimes. ICC Act, art. 19; Human Rights Watch interview with member of Uganda’s legal community, Kampala, September 22, 2011.

[12] See Geneva Conventions Act (Ch 363), art. 2; ICC Act, arts. 7-9; Penal Code (Ch 120), June 15, 1950, http://www.ulii.org/ug/legis/consol_act/pca195087/ (accessed October 26, 2011), for example, art. 189.

[13] JLOS, “Frequently Asked Questions on the International Crimes Division of the High Court of Uganda,” p. 5.

[14] ICD Practice Directions, para. 6.

[15]Amnesty Act (Ch 294), January 21, 2000, http://www.ulii.org/ug/legis/consol_act/aa2000111/ (accessed November 4, 2011), sec. 3(1)(b).

[16]Amnesty (Amendment) Act, 2006 (Ch 294), May 24, 2006, http://www.ucicc.org/documents/Legal/Amnesty(Ammendment)%20Act%202006.pdf (accessed December 9, 2011), sec. 2a.

[17]ICD Practice Directions, paras. 4-5.

[18] One of the judges previously worked as a Commonwealth judge, another worked at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the Special Court for Sierra Leone, and a third is from northern Uganda and trained in international law. There is significant controversy over the appointment of one of the justices, Anup Singh Choudry. Choudry is not on the bench of the ICD’s only trial involving serious crimes, of Thomas Kwoyelo. See Emmanuel Gyezaho, “Chief Justice Blasts Judge over Letter,” Daily Monitor (Uganda), July 7, 2011, http://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/-/688334/1196022/-/bym6bnz/-/index.html (accessed November 1, 2011); Tabu Butagira, “Law Society Asks President to Interdict Justice Choudry,” Daily Monitor (Uganda), May 7, 2011, http://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/-/688334/913758/-/wyjm2m/-/index.html (accessed November 15, 2011); Human Rights Watch separate interviews with two nongovernmental organization (NGO) observers, Kampala, September 19 and 20, 2011, and individual who works with the ICD, New York, December 14, 2011.

[19] Human Rights Watch interview with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011.

[20] Human Rights Watch separate and group interviews with four individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 20 and 23, 2011.

[21] For information on the role of registrars generally in Uganda, see Judicature Act (Ch 13), May 17, 1996, http://www.ulii.org/ug/legis/consol_act/ja123/ (accessed October 25, 2011), sec. 41, 43; Trial on Indictments Act (Ch 23), August 6, 1971, http://www.ulii.org/ug/legis/consol_act/toia222/ (accessed October 25, 2011), 3, 27(2), 58(2), 60.

[22] The spokesperson for the judiciary overall speaks publicly on ICD matters. Human Rights Watch interviews with NGO observer, Kampala, September 19, 2011, and individual who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011, and email correspondence with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, October 27, 2011. See also Public International Law and Policy Group (PILPG)/International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ)-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission, “Final Report and Recommendations of Needs-Assessment Mission Experts,” March 4, 2011 (“PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report”), paras. 84-102; 135-155, on file with Human Rights Watch.

[23] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with three individuals working with the ICD, Kampala, September 21 and 23, 2011.

[24]Human Rights Watch interview with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, September 21, 2011; JLOS, “Frequently Asked Questions on the International Crimes Division of the High Court of Uganda,” p. 4; Judiciary of the Republic of Uganda, “High Court Divisions: International Crimes Division.”

[25]Human Rights Watch separate interviews with two individuals working with the ICD, Kampala, September 21 and 23, 2011.

[26] See United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute and International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, ICTY Manual on Developed Practices, 2009, http://www.icty.org/x/file/About/Reports%20and%20Publications/manual_developed_practices/icty_manual_on_developed_practices.pdf (accessed December 9, 2011), p. 12, para. 8.

[27] See OTP, “Weekly Briefing,” issue no. 65, November 23-29, 2010, http://www.icc-cpi.int/NR/rdonlyres/7105B39A-2F30-43FF-9222-D7349BF15502/282732/OTPWBENG.pdf (accessed October 27, 2011), p. 1; OTP, “Weekly Briefing,” issue no. 78, March 8-14, 2011, http://www.icc-cpi.int/NR/rdonlyres/7E0F85AF-4A0E-4227-A8BB-0CA758ED96BE/283129/OTPWeeklyBriefing_814March2011.pdf (accessed October 27, 2011), p.1.

[28] Human Rights Watch interview with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, September 21, 2011. Earlier, in May 2010, ICD officials voiced concern over a lack of ICC response regarding their queries for assistance from the ICC with their investigations. Human Rights Watch interview with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, May 2010. See also PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011, para. 87.

[29] Human Rights Watch joint interview with two individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 23, 2011.

[30] See JLOS, “About Us,” undated, http://www.jlos.go.ug/page.php?p=about (accessed October 28, 2011).

[31] Human Rights Watch interviews with individual who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011, and individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, September 21, 2011. See also PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2o11, paras. 119, 125, 167.

[32] Bail hearings for the terrorism case before the ICD have been held at the division’s building.

[33] Constitution of the Republic of Uganda (1995), http://www.justice.go.ug/docs/constitution_1995.pdf (accessed October 25, 2011), art. 28(3)(e).

[34] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), adopted December 16, 1966, G.A. Res. 2200A (XXI), 21 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16) at 52, U.N. Doc. A/6316 (1966), 999 U.N.T.S. 171, entered into force March 23, 1976, ratified by Uganda on June 21, 1995, art. 14(3)(d).

[35] See PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011, para. 57. See also Human Rights Watch, Violence Instead of Vigilance: Torture and Illegal Detention by Uganda’s Rapid Response Unit, March 23, 2011,

http://www.hrw.org/reports/2011/03/23/violence-instead-vigilance, pp. 48-49.

[36] Human Rights Watch email correspondence with donors, Kampala, October 7, 2011. See also PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011, paras. 38-39.

[37] Human Rights Watch email correspondence with donors, Kampala, October 7, 2011.

[38] Lawyers in the case requested the transfer due to concerns over Justice Choudry presiding over the case. Human Rights Watch email communication with lawyers, November 10, 2011.

[39] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with three individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 21 and 23, 2011.

[40] ICCPR, art. 9(4).

[41] See OTP, “Weekly Briefing,” issue no. 65, November 23-29, 2010, http://www.icc-cpi.int/NR/rdonlyres/7105B39A-2F30-43FF-9222-D7349BF15502/282732/OTPWBENG.pdf (accessed December 30, 2011), p. 1.

[42] See JLOS, “Frequently Asked Questions on the Trial of Thomas Kwoyelo,” undated, http://www.jlos.go.ug/uploads/Thomas_kwoyelo_FAQs.pdf (accessed December 10, 2011); Human Rights Watch, Thomas Kwoyelo’s Trial Before Uganda’s International Crimes Division: Questions and Answers, July 2011, http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/related_material/Q&A%20Kwoyelo%20Trial.pdf.

[43]Uganda v. Kwoyelo Thomas, High Court of Uganda (War Crimes Division), Case No. 02/10, Indictment, August 31, 2010, on file with Human Rights Watch.

[44]Uganda v. Kwoyelo Thomas, High Court of Uganda (International Crimes Division), Case No. 02/10, Amended Indictment, July 5, 2011, http://www.judicature.go.ug/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_details&Itemid=91&gid=55 (accessed October 27, 2011), pp. 2-24.

[45] Human Rights Watch observation of proceedings, Gulu, July 11, 2011.

[46] See JLOS, “Justice at Cross Roads? A Special Report on the Thomas Kwoyelo Trial,” undated, http://www.jlos.go.ug/uploads/Special%20Report%20on%20the%20Thomas_kwoyelo_trial.pdf (accessed November 1, 2011), p. 1; Uganda Coalition on the International Criminal Court (UCICC), “Court Room Updates-Uganda: Uganda vs Thomas Kwoyelo Constitutional Reference No. 36/2011,” August 16, 2011, pp. 4-5, on file with Human Rights Watch.

[47] Human Rights Watch observation of the issuance of the ruling by Uganda’s Constitutional Court, Kampala, September 22, 2011. See also Thomas Kwoyelo v. Uganda, Constitutional Court of Uganda, constitutional petition no. 036/11, Judgment, September 22, 2011, pp. 23-24, on file with Human Rights Watch.

[48] See JLOS, “Justice at Cross Roads? A Special Report on the Thomas Kwoyelo Trial,” p. 9.

[49] Ibid., p. 3.

[50] See Amnesty Act (Extension of Expiry Period) Instrument 2010, Statutory Instruments Supplement No. 16, Acts Supplement, Uganda Gazette, no. 31, vol. CIII, May 21, 2010, http://www.beyondjuba.org/policy_documents/Amnesty_Act_Instrument.pdf (accessed November 8, 2011).

[51] For a detailed analysis of these issues, see Human Rights Watch, Benchmarks for Justice for Serious Crimes in Northern Uganda, September 2, 2008, http://www.hrw.org/news/2008/09/01/benchmarks-justice-serious-crimes-northern-uganda, pp. 5-11.

[52] Ibid., pp. 31-33, 43.

[53] For earlier analysis of some of these issues, see PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011; Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI), “Putting Complementarity into Practice: Domestic Justice for International Crimes in DRC, Uganda, and Kenya,” January 2011, http://www.soros.org/initiatives/justice/articles_publications/publications/complementarity-in-practice-20110119/putting-complementarity-into-practice-20110120.pdf (accessed November 5, 2011), pp. 58-82; Human Rights Watch, Benchmarks for Justice for Serious Crimes in Northern Uganda, pp. 21-34.

[54] Amnesty Act (Ch 294), January 21, 2000, http://www.ulii.org/ug/legis/consol_act/aa2000111/ (accessed November 4, 2011), sec. 3(1)(b).

[55] Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Nathan Twinomugisha, legal officer, Amnesty Commission, Kampala, July 8, 2011.

[56] See Human Rights Watch, Democratic Republic of Congo – The Christmas Massacres: LRA attacks on Civilians in Northern Congo, February 2009, http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/drc0209webwcover_1.pdf, p. 34. See also Human Rights Watch, Democratic Republic of Congo – Trail of Death: LRA Atrocities in Northeastern Congo, March 2010, http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/drc0310webwcover_0.pdf, pp. 16, 50, 65-66; Human Rights Watch telephone interview with Nathan Twinomugisha, legal officer, Amnesty Commission, Kampala, July 8, 2011.

[57] For more detailed analysis of this issue, see Human Rights Watch, Benchmarks for Justice for Serious Crimes in Northern Uganda, pp. 3-5; Human Rights Watch, Selling Justice Short: Why Accountability Matters for Peace, July 2009, http://www.hrw.org/node/84264, pp. 10-17.

[58] International Criminal Court Act (“ICC Act”), Acts Supplement No. 6, Uganda Gazette, no. 39, vol. CIII, June 25, 2010.

[59] See Human Rights Watch, Benchmarks for Justice for Serious Crimes in Northern Uganda, pp. 25-27.

[60] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with two individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 21, 2011, and New York, December 14, 2011, and one member of Uganda’s legal community, Kampala, September, 22, 2011. See also OSJI, “Putting Complementarity into Practice” January 2011, pp. 59-62.

[61] See Human Rights Watch, Benchmarks for Justice for Serious Crimes in Northern Uganda, pp. 16-19, 42.

[62] See Attorney General v. Susan Kigula and 417 Others, Supreme Court of Uganda, constitutional appeal no. 03 of 2006, January 21, 2009, http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/499aa02c2.html (accessed November 16, 2011). The Refugee Law Project reported that the ICD registrar publicly indicated that the ICD will not apply the death penalty, but this is insufficient to ensure against its application. Annelieke van de Wiel, “Witness to the Trial: Monitoring the Kwoyelo Trial,” Refugee Law Project, issue 1, July 11, 2011, http://www.refugeelawproject.org/others/Newsletter_on_Kwoyelo_trial_progress_Issue_1.pdf (accessed October 27, 2011), p. 1.

[63] See ICCPR, art. 6. See also Human Rights Watch, Benchmarks for Justice for Serious Crimes in Northern Uganda, pp. 20, 41.

[64] Human Rights Watch interview and email correspondence with two individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 21 and October 27, 2011. See also Cissy Makumbi, “Army Officers to Face Trial,” Daily Monitor (Uganda), July 25, 2011, http://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/-/688334/1207214/-/bl2jrhz/-/index.html (accessed October 25, 2011); Van de Wiel, “Witness to the Trial: Monitoring the Kwoyelo Trial,” Refugee Law Project, issue 1, p. 3. By contrast, the jurisdictional reach of the division as proposed in the Juba agreements was open to interpretation and arguably limited to LRA members. See Human Rights Watch, Benchmarks for Justice for Serious Crimes in Northern Uganda, pp. 24-25, 44. The NRA became the UPDF in 1995.

[65] See Human Rights Watch, Benchmarks for Justice for Serious Crimes in Northern Uganda, pp. 24-25; Human Rights Watch, Uprooted and Forgotten, pp. 41-48.

[66] The OTP’s investigations may have revealed, for example, that while crimes were committed by UPDF forces, these crimes fell outside the court’s temporal jurisdiction—which began only in 2002, fairly late in the course of the LRA conflict and after some of the most serious abuses allegedly implicating Ugandan forces may have been committed. For a more detailed discussion of these issues, see Human Rights Watch, Unfinished Business: Closing Gaps in the Selection of ICC Cases, September 2011, http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/icc0911webwcover.pdf, pp. 24-29.

[67] ICCPR, art. 14(3)(b); Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, art. 28.

[68] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with two individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 20 and 22, 2011.

[69] Some lawyers queried whether the government could provide financial assistance to the defense as Kwoyelo secured counsel privately, but this was not cited as a basis for lack of support, rather that defense assistance is already part of JLOS’s budget. Human Rights Watch separate and joint interviews with four individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 20 and 23, 2011.

[70] Human Rights Watch interview with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011; PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011, para. 60.

[71] Human Rights Watch interview with Thomas Kwoyelo, Luzira prison, November 17, 2009.

[72] Human Rights Watch separate and joint interviews with three individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 20 and 23, 2011.

[73] Human Rights Watch interview with individual who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011, and separate and joint interviews with three individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 22 and 23, 2011. See also PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011, paras. 57, 68.

[74] See Soon Yeon Kong Kim and Another v. Attorney General, Constitutional Court of Uganda, Constitutional Reference No. 06/2007, Judgment, March 7, 2008, http://www.ulii.org/ug/cases/UGCC/2008/2.html (accessed November 3, 2011). Human Rights Watch separate and joint interviews with five individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 21, 22, and 23, 2011. See also PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011, paras. 59-60, 67; Human Rights Watch, Benchmarks for Justice for Serious Crimes in Northern Uganda, pp. 28-29.

[75] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with two individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 21 and 23, 2011.

[76] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with two individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 20 and 22, 2011.

[77] See JLOS, “Frequently Asked Questions on the International Crimes Division of the High Court of Uganda,” p. 1.

[78] PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011.

[79] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with four individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 21 and 22, 2011, and one member of Uganda’s legal community, Kampala, September 22, 2011.

[80] Human Rights Watch interview with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, September 21, 2011; Uganda v. Kwoyelo Thomas, High Court of Uganda (International Crimes Division), Amended Indictment, http://www.judicature.go.ug/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_details&Itemid=91&gid=55 (accessed December 30, 2011). It should be noted that the terrorism case before the ICD is also very large as compared to ordinary criminal cases, with 14 defendants and nearly 100 counts charged.

[81] Human Rights Watch interview and email correspondence with two individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 20 and October 27, 2011. See also PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011, para. 129.

[82] Human Rights Watch group interview with three individuals who work with the ICD and one individual who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011, and email correspondence with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, October 27, 2011.

[83] Human Rights Watch separate and joint interviews with three individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 20 and 23, 2011.

[84] Human Rights Watch email correspondence and interview with two individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala and New York, October 27 and December 14, 2011.

[85] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with two individuals who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September 21 and 23, 2011, and email correspondence with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, October 27, 2011.

[86] Human Rights Watch interview with individual who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011.

[87] Human Rights Watch interviews with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, September 23, 2011, and individual who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011.

[88] Human Rights Watch interview with individual who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September, 23, 2011, and email correspondence with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, October 27, 2011.

[89] Human Rights Watch separate and joint interviews with four individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 21 and 23, 2011, and email correspondence with donors, Kampala, October 7, 2011, and individual who works with ICD, October 27, 2011. For a review of legal protections that exist, see “Uganda Context on Victim and Witness Protection,” Frank N. Othembi, secretary, Uganda Law Reform Commission, presentation at the Judicial Colloquium on Victim and Witness Protection and the Administration of Justice, Bomah Hotel, Gulu, Uganda, August 1, 2011, http://www.jlos.go.ug/uploads/ULRC%20Presentation_Mr.%20Frank%20Othembi%20(1).pdf (accessed November 8, 2011), p. 2; PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011, para. 92; Human Rights Watch, Benchmarks for Justice for Serious Crimes in Northern Uganda, pp. 31-32.

[90] While the process was underway before the ICD was established, the ICD’s creation appears to be helping to spur its finalization. Human Rights Watch interview with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, September 21, 2011, and email correspondence with donors, Kampala, October 7, 2011.

[91] This is an area where the ICD’s needs intersected with the OHCHR’s priorities on transitional justice mechanisms that comply with international standards on witnesses and victims. Human Rights Watch joint interview with two individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 23, 2011. See also OHCHR, Concept Note, Judicial Colloquium on Victim and Witness Protection, August 2011, http://www.jlos.go.ug/uploads/Concept%20Paper-Victim%20and%20Witness%20Protection%20Judicial%20Workshop%20in%20Uganda%20Aug%202011.pdf (accessed October 28, 2011); OHCHR, The Protection of Victims and Witnesses: A Compilation of Reports and Consultations in Uganda, 2010, on file with Human Rights Watch.

[92] Human Rights Watch separate and joint interviews with three individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 19 and 23, 2011, interview with NGO observer, Kampala, September 19, 2011, and email correspondence with donors, Kampala, October 7, 2011.

[93] Human Rights Watch interviews with NGO observer, Kampala, September 20, 2011, two individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 21 and 22, 2011, and member of Uganda’s legal community, Kampala, September 22, 2011.

[94] Ordinarily, anyone in a courtroom who can assist (i.e., clerks, guards, etc.) provides informal interpretation when it is needed. PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011, paras. 76-79.

[95] Human Rights Watch joint interview with two individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 23, 2011. See also JLOS, “JLOS with Support from DANIDA to facilitate the Training of Court Interpreters,” June 20, 2011, http://www.jlos.go.ug/page.php?p=curnews&id=54 (accessed October 28, 2011).

[96] Human Rights Watch observation of opening of trial, Gulu, July 11, 2011.

[97] Human Rights Watch observation of opening of trial, Gulu, July 11, 2011; informal summary of proceedings by observer, July 25, 2011, on file with Human Rights Watch.

[98] Human Rights Watch interview with NGO observer, Kampala, September 19, 2011, and email correspondence with donors, Kampala, October 7, 2011.

[99] ICCPR, art. 14(3); Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, arts. 23(3), 28(3).

[100] Human Rights Watch interviews with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, September 19, 2011, ICC staff, Kampala, September 21, 2011, and two NGO observers, Kampala, September 19 and 20, 2011.

[101] See Okumu Langol Livingstone, Ephraim Kasozi and Juliet Kigongo, “Kwoyelo for Trial,” Daily Monitor (Uganda), July 11, 2011, http://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/-/688334/1198436/-/bykoihz/-/index.html (accessed November 1, 2011); Cissy Makumbi, “Army Officers to Face Trial,” Daily Monitor (Uganda), July 25, 2011; Sam Lawino, “War Victims Mark International Day of Justice in Gulu,” Acholi Times (Uganda), July 25, 2011, http://www.acholitimes.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=122:pretty-b (accessed October 25, 2011).

[102] PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011, paras. 160-162.

[103] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with one individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, September 21, 2011, and two individuals who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September 20 and 23, 2011. See also Judiciary of the Republic of Uganda, “High Court Divisions: International Crimes Division.”

[104] See Van de Wiel, “Witness to the Trial: Monitoring the Kwoyelo Trial,” Refugee Law Project, issue 1, p. 3; Moses Akena and Sam Lawino, “Leaders Criticise ICC Laws,” Daily Monitor (Uganda), July 15, 2011, http://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/-/688334/1201404/-/bl6o5hz/-/index.html (accessed November 5, 2011); Human Rights Watch separate interviews with two NGO observers, Kampala, September 19 and 20, 2011, and group interview with three individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011.

[105] See JLOS, “Frequently Asked Questions on the International Crimes Division of the High Court of Uganda,” and “Frequently Asked Questions on the Trial of Thomas Kwoyelo,” undated; Human Rights Watch separate interviews with two NGO observers, Kampala, September 19 and 20, 2011.

[106] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with one NGO observer and one individual who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011.

[107] Human Rights Watch joint interview with two individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 23, 2011.

[108] JLOS also has a “Publicity Committee,” but the committee has never discussed the ICD. Human Rights Watch interviews with NGO observer, Kampala, September 20, 2011, individual who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011, individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, September 23, 2011, and DPP official, Kampala, September 23, 2011, joint interview with two individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 23, 2011, and email correspondence with donors, Kampala, October 7, 2011.

[109] See for example, Office of Outreach and Public Affairs, Special Court for Sierra Leone, “About: Office of Outreach and Public Affairs,” undated, http://www.sc-sl.org/ABOUT/CourtOrganization/TheRegistry/OutreachandPublicAffairs/tabid/83/Default.aspx (accessed November 5, 2011); Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, “Jurisdiction, Organization, and Structure of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina,” undated, http://www.sudbih.gov.ba/?opcija=sadrzaj&kat=3&id=3&jezik=e (accessed November 5, 2011).

[110] Human Rights Watch interview with individual who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011, and separate and joint interviews with four individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 21 and 23, 2011.

[111] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with three NGO observers, Kampala, September 19 and 20, 2011.

[112] Human Rights Watch interview with NGO observer, Kampala, September 20, 2011.

[113] For a discussion of outreach strategies at the ICC, see Human Rights Watch, Courting History: The Landmark International Criminal Court’s First Years, July 2008, http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/icc0708_1.pdf, pp. 116-148.

[114] Other useful measures include in-person meetings and debates with affected communities, which can in some instances be arranged with assistance or in partnership with nongovernmental organizations.

[115] PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011.

[116] PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report; Human Rights Watch email correspondence with donors, Kampala, October 7, 2011.

[117] PILPG/ICTJ-Facilitated Needs-Assessment Mission Final Report, March 2011, para. 66.

[118] Ibid., para. 52; Human Rights Watch interview with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, September 23, 2011.

[119] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with four individuals who work with the ICD, Kampala, September 19, 20, 21, and 22, 2011, interview with individual who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011, and email correspondence with donors, Kampala, October 7, 2011. See also, for example, International Criminal Law Services, “Projects: Building Capacity in Uganda: Trainings for Practitioners,” undated, http://www.iclsfoundation.org/projects (accessed November 5, 2011).

[120] Human Rights Watch interviews with individual who works with the ICD, Kampala, September 19, 2011, and individual who worked with the ICD, Kampala, September 20, 2011, and email correspondence with donors, Kampala, October 7, 2011.

[121] Human Rights Watch email correspondence with Bosnian War Crimes Chamber staff, Sarajevo, October 7, 2011.