(Guatemala City) – Thousands of patients with advanced illnesses in Guatemala suffer unnecessarily from severe pain because they cannot get appropriate pain medications, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

Ensuring Access to Pain Treatment in Guatemala

The 62-page report, “‘Punishing the Patient’: Ensuring Access to Pain Treatment in Guatemala,” documents how Guatemala’s drug control regulations – meant to prevent drug abuse – make it almost impossible for many patients with cancer and other advanced illnesses to get strong pain medicines like morphine. Patients described their extreme pain and other symptoms and how they struggled to cope with a dim prognosis. They said they had to make visits to multiple doctors because many were unable to adequately treat pain, and many said they faced lengthy travel on crowded buses to reach hospitals that offer pain treatment.

“Many patients in Guatemala face unbearable suffering at the end of life, but it doesn’t have to be that way,” said Diederik Lohman, acting health director at Human Rights Watch. “With a few simple, inexpensive steps, the government can drastically improve the plight of these patients.”

The report is based on in-depth interviews with 79 people – including 37 people with cancer, or their relatives – and 38 healthcare workers. Human Rights Watch also identified the lack of palliative care policies and the fact that none of Guatemala’s medical schools include instruction on palliative care for medical students as barriers to proper medical care at the end of life.

Human Rights Watch estimates that at least 5,000 Guatemalans with cancer and HIV/AIDS live and die in pain per year because they cannot get morphine or other opioid analgesics. It said that about 28,500 Guatemalans – including around 1,500 children – require palliative care each year. These numbers are likely to increase with gains in life expectancy in Guatemala.

The World Health Organization considers morphine an essential medicine for treatment of moderate to severe pain.

As morphine is made from the poppy plant, international law requires governments to regulate who can get the medication and how. Such regulations should strike a balance between ensuring that patients can get morphine when they need it and preventing misuse, Human Rights Watch said.

But Human Rights Watch concluded that Guatemala’s regulations did not strike that balance. Instead, the regulations are almost myopically concerned with controlling opioid pain medicines, with little consideration for patients. Its regulations are far more restrictive than mandated by international law and are out of step with those of other countries in the region, such as Costa Rica, Mexico, and Panama.

Gabriel Morales, a cancer patient, told Human Rights Watch that he had to travel more than seven hours every 10 to 15 days on public buses to get pain medications for abdominal cancer in Guatemala City: “I would wake up at 1 a.m., walk about half a kilometer, and catch the 2:30 a.m. bus. I would get to the boundary of Guatemala City around 8 a.m., where I would take a second bus to the center of the city.”

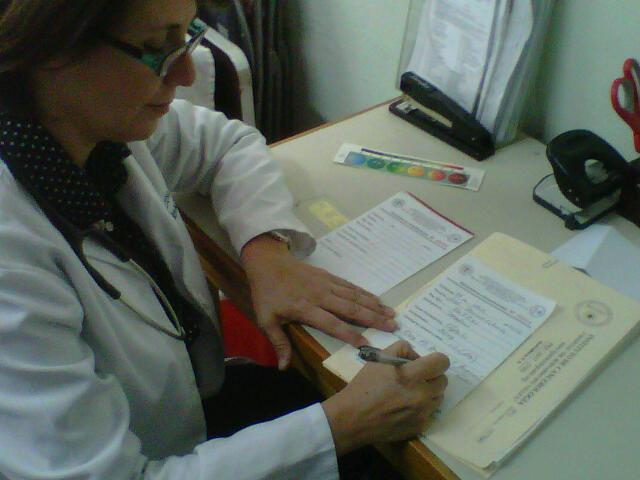

A doctor said: “I mourn for all the patients I can’t see. There are so many people who don’t have access to a doctor who can prescribe opioids or even someone to refer them to a doctor who can.” Only 50 to 60 doctors out of about 14,000 doctors in the country, all of them in Guatemala City, can prescribe morphine. This is because under Guatemala’s regulations, a physician must use a special prescription pad to prescribe morphine and other opioid analgesics, but the procedure for getting the pad is needlessly complicated, Human Rights Watch found.

Doctors should not have to push the boundaries of the law to provide proper care to their patients.

Diederik Lohman

Acting director, Health and Human Rights Division

Patients or their families must then obtain a stamp from a Health Ministry office in Guatemala City to validate the prescription before a pharmacy can dispense the medications. Human Rights Watch is unaware of any other country that requires this kind of validation, which makes it practically impossible for many patients to get the medication.

Human Rights Watch found that Guatemala’s restrictive regulations pose an acute ethical dilemma for physicians. Often, they cannot offer proper care to patients, as required by their professional oath, without stretching or breaking the law and thus exposing themselves to potential disciplinary or criminal penalties.

Some hospitals in Guatemala City have found creative solutions to circumvent the complex procedure by allowing hospital pharmacies, which normally provide medicines only to hospitalized patients, to dispense morphine to patients who are not hospitalized. This practice, which several consecutive governments have tolerated, has alleviated the situation for some patients, but a permanent and country-wide solution is urgently required, Human Rights Watch said.

Several doctors also said that they accepted and reused opioid analgesics that families have left over when a loved one dies – a practice that is not legal in Guatemala but has also been tolerated. A few healthcare workers said that they told their patients to try buying pain medicines on the black market since obtaining them legally was not feasible.

“Doctors should not have to push the boundaries of the law to provide proper care to their patients,” Lohman said, “This government has an opportunity to solve this longstanding problem once and for all.”