Summary

Joseph Koostachin, 58, remembers when he and his wife Helen, 56, went out on the land to hunt and berry pick with their young children. In the summer, the forests and meadows were lush and the water in the rivers plentiful. The winters were cold, with ice and snow cover allowing them to travel by dog sled from November through April. They would hunt caribou, a large type of deer, in the winter, while snow geese predictably arrived in April, and fish were bountiful in summer. The varied, seasonal harvest helped Joseph feed his family healthy food year-round.

The Koostachins live in Peawanuck, a remote community on Hudson Bay in the Canadian province of Ontario. Joseph and Helen’s sons are now grown and have taken over the responsibility of securing food from the land for the family. Going out on the land means more than just finding food, however, it is also a reflection of their deep ties to the land of their ancestors and its importance to their cultural identity and traditions.

Yet as global temperatures have risen as a result of climate change, the Koostachins’ way of life, and livelihood, have become increasingly difficult to maintain, and the realization of their rights to food, health, and culture are at risk. There are fewer caribou and geese migrating to the area. And it is harder—at times impossible—to hunt them because the ice and permafrost they must travel over is no longer stable throughout the winter, while the waters they traverse in summer are unpredictably low. As the climate continues to warm, these changes to their lands and environment will intensify, and their traditional sources of sustenance could entirely disappear.

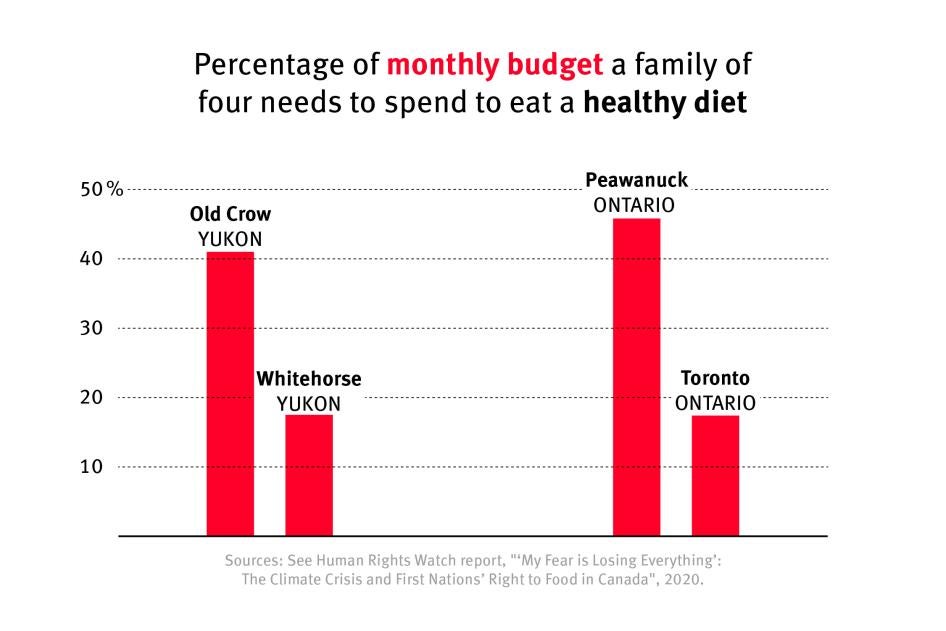

Already, as a result of these changes, the Koostachins have not been able to harvest the food they need to ensure an adequate diet, and, like many northern and remote First Nations people in Canada, they lack a cost-effective, healthy alternative. If not enough food can be harvested from the land—through hunting, fishing, and gathering wild plants—their only option is to buy costly food imported from the [Canadian] “South.” An average family of four in Peawanuck must spend around 30 percent more to purchase a standard selection of healthy food each month compared to a family in Toronto.

With their modest income, the Koostachins said they cannot afford to buy healthy food such as vegetables at the store. While there are government subsidies meant to make food shipped from the South more affordable, healthy imported food, particularly produce, remains inaccessible to many and is becoming more expensive as a result of climate impacts on transport costs.

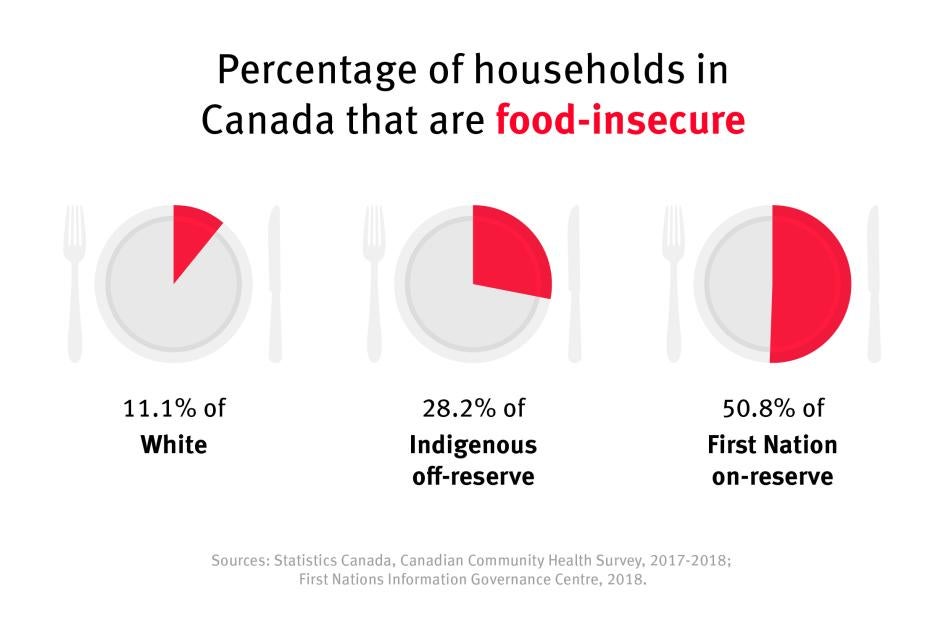

Across Canada, Indigenous families are already much more likely to be “food insecure”—defined by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as not being able to access food to meet dietary needs and food preferences—largely as a result of historic marginalization and the impacts of colonialism. Some studies find nearly one in two households in First Nations are food insecure, compared with one out of nine white Canadian households. Food poverty now risks reaching increasingly dangerous levels as climate change impacts across the country intensify and accelerate, undermining First Nations’ access to food and worsening health outcomes, especially for adults and children with chronic health conditions such as diabetes.

Climate change is significantly impacting First Nations—and their livelihoods—across Canada, and there is evidence that the worst is yet to come. Canada is warming by about twice the global average, and northern Canada is warming even faster. A 2019 government report, commissioned by the federal climate ministry, projects increasingly warmer temperatures, shorter snow and ice cover seasons, and thawing permafrost across the country. In fact, key sub-Arctic ecosystems that support many traditional sources of food are already at risk of reaching climate tipping points, past which they will not be able to recover from the consequences of rapid warming. This change, according to scientists, will contribute to carbon emissions. For example, climate change-induced permafrost thaw and increased forest fires are pushing historic carbon sinks like Canada’s vast boreal forest to the brink, causing them to become net carbon contributors.

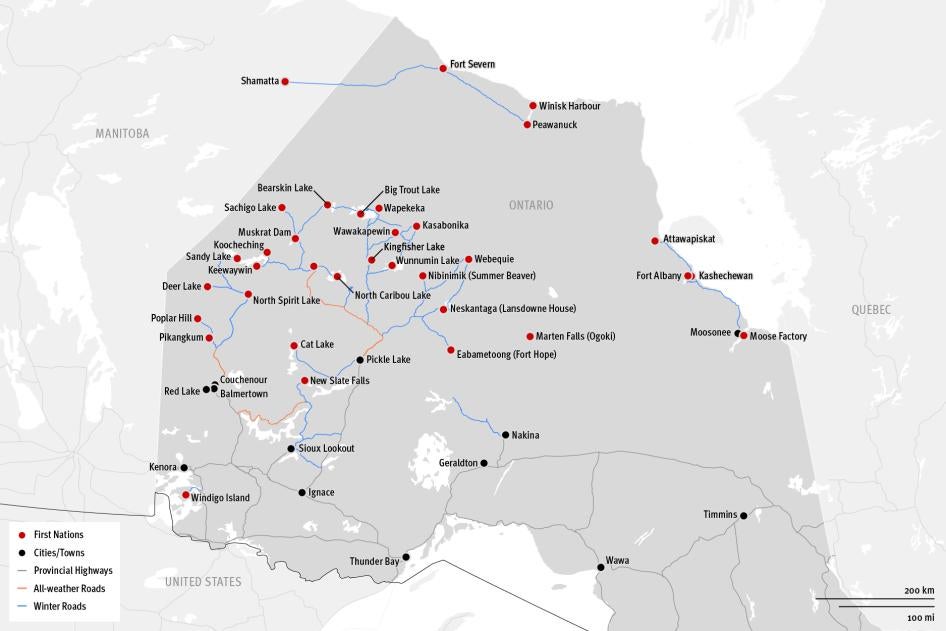

Indigenous peoples in Canada are among the lowest contributors to greenhouse emissions in the country, yet academic research shows they are among the most exposed to climate change impacts. As the climate warms, there are fewer animals migrating and traditional plants growing on First Nations’ traditional territories. Unpredictable weather hampers the ability of hunters, who rely on traditional knowledge, to safely navigate potentially treacherous terrain to access hunting grounds. And as transport options like winter roads—constructed from snow and ice—become less reliable in warming winters, communities increasingly rely on more expensive air transport to deliver food, driving up the cost of purchased foods.

The harmful impacts of warming that Indigenous populations in Canada are experiencing point to more devastating impacts in the future. Human Rights Watch research found that the Canadian government’s failure to put in place adequate measures to support First Nations in adapting to current and anticipated impacts of climate change is leading to violations of their rights. And federal and provincial authorities are not doing enough to advance global efforts to curb climate change.

This report, the outcome of research Human Rights Watch conducted in Northern Ontario, Northwestern British Columbia, and Northern Yukon between June 2018 and December 2019, examines the impacts of the climate crisis on First Nations. Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 120 individuals, including residents, chiefs, and council members in First Nations communities; medical providers, educators, environment and health experts, academics, and staff of Indigenous-led and Indigenous representative organizations. The experiences of First Nations described in this report are illustrative of broader climate change impacts across Canada, however, each First Nation is unique, and none of their experiences can be generalized, making it imperative to tailor measures to address climate impacts and community needs in each of their traditional territories.

Climate Change as a Driver of Food Poverty

The communities Human Rights Watch visited are largely populated by First Nations people who have traditionally relied on caribou, moose, geese, salmon and other animals and fish—along with supplements of berries—to feed their families. For generations, traditional food systems have been central to the livelihoods and health of First Nations.

Climate change threatens to decimate these food systems, risking further serious consequences for livelihoods and health. In the three areas where Human Rights Watch conducted research, residents reported drastic reductions in the quantity of harvestable resources available, and increased difficulty and danger associated with harvesting. They attributed this decline in part to changes in wildlife habitat as a result of climate change, including changing ice and permafrost, wildfires, warming water temperatures, changes in precipitation and water levels, and unpredictable weather. Numerous scientific studies support these observations and warn of further devastating impacts as the climate crisis increasingly threatens the viability of and access to traditional food sources.

With less food to be harvested, households supplement their traditional diet with more purchased food. First Nations in remote locations have a compounded risk of food poverty because higher transportation costs drive food prices higher than elsewhere in the country. This cost differential has been increasing in part due to climate-related changes in the local environment. For example, shorter, warmer winters mean shorter periods in which winter roads can be used, and such roads enable more cost-effective delivery of supplies from the South. This change means more people like Joseph and Helen choosing between going hungry or buying cheaper foods they believe contribute to making them sick or sicker. It will get significantly worse if climate change continues unchecked.

Impacts on Health and Culture

Healthy foods, such as fruits and vegetables, in remote grocery stores are often cost-prohibitive. As a result, people told Human Rights Watch they tend to eat more affordable, but less nutritious foods, compounding existing health disparities in northern communities tied to historic marginalization and poor access to health care. In particular, academic studies show that increased dependence on processed, high-calorie, store-bought foods—often less expensive and with longer shelf-lives—has contributed to serious diet-related health issues among First Nations, such as the growing and disproportionate number of First Nations people affected by obesity and diabetes.

In several of the communities where Human Rights Watch conducted research, teachers and community members said that children come hungry to school. Older people and people with chronic diseases whose health conditions can make a healthy diet all-the-more critical said they find the loss of harvested food impedes their ability to eat healthily. Medical providers told Human Rights Watch that people with chronic diseases cannot afford to follow medically recommended diets due to their inability to obtain food from the land or to afford nutritious foods sold in stores. Some of the relatively older people interviewed for this report said they have cut down on the number of meals they eat per day.

The impacts of climate change negatively affect Indigenous cultures. Limited access to traditional food sources and decreased ability of First Nations to safely spend time on the land, threatens not only communities’ food supplies but also their ability to engage in related cultural practices and ultimately maintain their cultural identities. First Nations’ land-based knowledge systems, known as “Indigenous knowledge,” which communities use to pass information about harvesting techniques and other cultural knowledge down through the generations, are also being challenged by climate change impacts. The unpredictable weather and animal patterns linked to climate change impacts inhibit the growth and adaptation of Indigenous knowledge, and the transmission of cultural knowledge—which necessitates time spent on the land.

Community Resilience in the Face of the Climate Crisis

Across the country, First Nations are addressing the impacts of the climate crisis, including through projects such as community solar projects or local food sourcing projects like gardens and greenhouses. Some First Nations maintain strong traditional food sharing networks that have helped address climate-driven loss of food through sharing harvest with vulnerable members of the community, while others have built up community-science programs that monitor climate change impacts on their environment. Yet, all these efforts require resources and capacity which many communities cannot access given government funding complexities, especially as needs increase with rising temperatures.

Failure to Address Climate Change and its Impacts on Food Poverty

In its September 2020 Speech from the Throne, in which the federal government outlines its priorities for the upcoming parliamentary session, the government committed to “work with … First Nations … to address food insecurity in Canada.” Until now, federal climate change policies have largely ignored the impacts of climate change on First Nations’ right to food. Most existing policies were designed without meaningful participation of First Nations and fail to monitor—let alone address—human rights impacts in these communities. Food subsidies and health resources required to respond to the current and projected impacts are often not available, insufficient, or do not reach those who need it the most.

For example, the federal government’s “Nutrition North” program subsidizes a list of nutritious foods transported from registered southern retailers. This program is the major means of supplementing inadequate supplies of locally harvested food. However, since its inception in 2011, the program has not led to remote, northern communities securing access to affordable, healthy food: food prices in community-based stores remain high with healthy food options financially unattainable for many. Ordering subsidized food from retailers in the South often requires a credit card—which can be a barrier for some low-income families. It remains to be seen whether changes to the program made in 2019, including subsidy increases, will increase access to healthy foods in First Nations. Robust community-based monitoring of actual price development in First Nations should be undertaken to determine the efficacy of these changes and adjustments made where necessary.

At the subnational level of provincial and territorial governments the response varies. The Yukon territory, for example, released a climate change policy in 2019 that acknowledges the need to monitor and address food security and unique impacts on Indigenous peoples. Ontario, by contrast, starting in 2018, cancelled numerous climate adaptation and mitigation programs that benefited First Nations.

Meanwhile, Canada is not doing its part to advance global efforts to address the change in global temperature, which is contributing to loss of traditional food sources. In 2015, it made a weak pledge to only reduce emissions by 30 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. At time of writing Canada has not set an adequately ambitious Nationally Determined Contribution, a country’s domestic climate change action plan, to keep global temperature rise below 1.5°C—according to the think tank Climate Action Tracker, if all government targets were in range with Canada’s level of ambition, warming would reach over 2°C and up to 3°C. While the federal government has repeatedly confirmed its commitment to exceed the 2030 goal and reach net-zero emissions by 2050 through legislated targets, including in the September 2020 Speech from the Throne, it is unclear how it will reach these goals. In any case, the government is not on track to meet either its 2030 emissions targets or net-zero by 2050, and acknowledges that more needs to be done. Despite its relatively small population of approximately 37.5 million people, Canada is still among the top 10 countries worldwide in GHG emissions, with per capita emissions approximately three to four times the global average, and growing.

Complicating efforts to cut emissions is Canada’s continued subsidizing of fossil fuel production. Canada increased its financial support for fossil fuels from 2018 to 2019 to nearly CAD$600 million, and has continued to provide billions in aid to fossil fuel producers as part of the country’s Covid-19 response in 2020.

The federal government’s plan to cut carbon emissions through a carbon pricing policy can be an essential aspect—though insufficient on its own—of the fight against climate change. The current design of the federal carbon tax, however, will likely drive up food prices, particularly in remote communities, thereby placing a disproportionate burden on a population that bears the least responsibility for the problem. While the policy includes a tax-based rebate intended to mitigate the impacts of these price increases on lower-income people, the federal government has acknowledged this method is ineffective for First Nations given legislated tax exemptions that mean many First Nations people on-reserve do not file federal tax returns.

Ultimately, Canada’s climate policies are insufficient and poorly designed, contributing to a double bind for First Nation peoples: while climate change is adversely impacting their traditional food sources, their ability to afford healthy store-bought food is being undercut by the government’s main mitigation policy: the carbon tax.

Recommendations

The Canadian government should urgently strengthen its climate change policies to reduce emissions in line with the best available science, including by setting ambitious new Nationally Determined Contributions which will align their emissions reduction targets with the Paris Agreement.

Covid-19 stimulus packages should support a just transition towards renewable energy, including in First Nations. Such measures are essential for Canada to contribute to global efforts to mitigate climate change under the Paris Agreement, which are necessary to reduce further negative impacts on Indigenous peoples’ rights to food and health.

First Nations should receive the financial and technical support needed to respond to current and projected climate impacts, including on food and health, and should lead the design and implementation of programs addressing these impacts.

In line with Canada’s human rights obligations, including under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, it is essential that climate change adaptation and mitigation policies not further harm Indigenous peoples, including older people, women, children and people with chronic diseases within First Nations who are already among the most impacted by climate change.

The Canadian government should publicly announce that it accepts the right to food as a basic human right, and part of the human right to an adequate standard of living, and realize its obligation to ensure that First Nations can realize this right by addressing climate impacts on food poverty. The announcement should include a recognition that Indigenous knowledge of climatic conditions and their impacts on traditional food sources are relevant to the realization of the right to food.

Methodology

This report documents the impacts of climate change on First Nations’ rights to food, health, culture, and a healthy environment in communities in both the Far North and provincial norths of Canada. It also examines government policies related to climate change mitigation and adaptation and how the government is addressing the human rights challenges exacerbated by climate change. The report is based on interviews with more than 120 people, including 45 Indigenous people living in First Nations on and off reserve, provincial/territorial and federal government officials, and representatives of nongovernmental organizations who have worked on climate change impacts in First Nations. Human Rights Watch also interviewed more than 30 experts who currently work, or have worked, on Indigenous food security and climate change issues, including service providers and academic researchers.

The interviews were conducted in person and by phone between June 2018 and March 2020, including five weeks of field research in June and October 2018, March and December 2019, and March 2020. We also conducted group interviews, each of between five and 15 participants, in Peawanuck and Old Crow. Human Rights Watch identified interviewees through community members who had monitored climate change impacts or had volunteered during community meetings organized to introduce our work. Interviews were conducted in English, or in Cree via an interpreter. Human Rights Watch researchers obtained oral informed consent from all interview participants, and provided oral explanations about the objectives of the research and how interviewees’ accounts would be used in the report. Interviewees were informed that they could stop the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions they did not feel comfortable answering. Interviewees were not compensated.

Field research for this report was conducted in First Nations in Yukon territory (Old Crow) and in Ontario (Peawanuck, Attawapiskat) and British Columbia (Skeena River watershed) provinces. These communities were chosen because they represent a variety of climatic zones and related traditional food sources, different levels of remoteness (fly-in communities as well as road accessible), different carbon pricing regimes (provincial and federal) as well as different community structures, (self-) government status and sizes. Researchers also conducted interviews in Whitehorse (Yukon), Toronto (Ontario), Victoria (British Columbia), and Ottawa (Ontario).

Researchers also reviewed and analyzed secondary sources—including academic research and peer-reviewed scientific studies documenting and projecting the impacts of climate change, media reports, and relevant Canadian laws and policies.

Human Rights Watch sent letters to the Prime Minister’s Office; the ministers of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC), Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), Health Canada, and Agriculture and Agri-food Canada; relevant staff at CIRNAC, ISC, ECCC, Health Canada, and Natural Resources Canada; and to the premiers of Ontario, British Columbia, and Yukon in June and July 2020. The letters provided a summary of Human Rights Watch findings, included specific questions for the government, and offered to reflect the government’s response in the report. At time of writing, written responses were received from CIRNAC, ISC, ECCC, Natural Resources Canada, Health Canada, and the governments of Yukon and Ontario and are published on the Human Rights Watch website, linked to this report. No written response was received from Agriculture and Agri-food Canada, or the government of British Columbia.

Human Rights Watch also sent letters to The North West Company and Arctic Co-op Ltd., the two largest food retailers in remote and northern communities, in July 2020. The letters provided a summary of Human Rights Watch findings, included specific questions, and offered to reflect the company’s response in the report. At time of writing, The North West Company met with Human Rights Watch, in addition to providing responses via email, but no response was received from Arctic Co-op Ltd.

Each First Nation is unique and none of the experiences described in the report can be generalized.

Terminology:

Elder: In First Nations, the term “Elder” is used to refer to someone who has attained a high degree of understanding of the community’s history, traditional teachings, and ceremonies, and earned the right to pass this knowledge on to others and to give advice and guidance. There is no specific age associated with the title “Elder,” though most Elders are older people. [1]

Right to food: This report uses the human right to food as defined under international human rights law to refer to the right of First Nations to have access to sufficient quantities of healthy, nutritious, and culturally appropriate foods. See the “Right to Food” section for more detail.

Food insecurity and food poverty: The terms “food poverty” and “food insecurity” are sometimes used interchangeably in public debate around reliance on food aid. This report uses “food poverty” to describe lack of consistent access to adequate healthy food, or more specifically, decreasing affordability and access to nutritious and traditional food sources for First Nations, and the related impacts on health and culture. “Food security” and “food insecurity” are only used when referring to more formal, systemic measurements of access to food at the individual or household level, which may not reflect additional variables of food poverty, such as whether a household has access to culturally-acceptable food.

First Nations in the Report

Weenusk First Nation, Ontario

The people of Weenusk First Nation have lived in the Hudson Bay Lowlands for generations. Today, the overall membership of Weenusk First Nation is about 595, approximately 300 of whom reside in Peawanuck.[2] Peawanuck is located in Ontario’s far north, on the Weenusk River along the shore of Hudson Bay and is accessible only by plane or ice-road during winter months. Weenusk First Nation became a party to Treaty #9, one of the historic treaties between First Nations and the Canadian government, in 1929-1930.[3]

Members of Weenusk First Nation hunt geese and other birds in the spring and fall when they migrate past the community. In the summer, they fish for trout, pike, and whitefish, among others, and go berry picking. In late fall they hunt moose. Caribou season runs throughout the fall and winter.

When substituting harvested food with store-bought food, community members rely on the Northern store on-reserve, though some order food from other vendors in Timmins, Ontario, over 750 km away. Only one winter road seasonally connects Peawanuck to the neighbouring province of Manitoba, stretching 772 km east along the Hudson Bay tree line and operating for about two months each winter.[4]

Attawapiskat First Nation, Ontario

Attawapiskat First Nation is located along the Attawapiskat River, five kilometers inland from James Bay. There are over 2,800 members of Attawapiskat First Nation, but the local on-reserve population is 1,501.[5] Attawapiskat became a party to Treaty #9, one of the historical treaties, in 1930.[6]

Attawapiskat First Nation members hunt moose mainly in the fall, caribou mainly during the winter when winter roads and ice and snow cover provide better inland access by snowmobile, and waterfowl during spring and fall migration periods.

Community members supplement harvested food with store-bought items, purchased at the on-reserve Northern Store or a locally-owned convenience store.[7] During the summer, supplies can be delivered by barge to Attawapiskat. During winter, the community is accessible by winter road for two months on average, depending on snow and ice condition.[8]

Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation, Yukon

Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation (VGFN) has a population of approximately 800, with about 250 people living mainly in Old Crow, located at the confluence of the Crow and Porcupine Rivers in the northern Yukon without any road access.[9] The Vuntut Gwitchin have settled their land claims with the government, defining their traditional territory, approximately 50,000 square miles (roughly 129,499 square kilometers), which is located mostly in the Northern Yukon region. The VGFN final agreement, signed with the governments of Canada and the Yukon in 1993, gives the First Nation responsibility to uphold the rights and freedoms of its Citizens and enact laws on natural resource protection and harvesting of traditional food sources.[10]

The community primarily relies on caribou for food, specifically, the Porcupine Caribou Herd (PCH), who migrate through Vuntut Gwitchin lands each spring and fall.[11] The community also harvest duck and geese in the spring, and whitefish and salmon from the Porcupine River during the summer. Moose and other, smaller animals are harvested as needed year-round. Harvesting takes place up and down the Porcupine River and in Crow Flats.[12] Community members supplement harvested food with store-bought food from a locally-operated Co-op or order from vendors in Whitehorse, arranging shipping via Air North, an airline that is partly owned by the Vuntut Gwitchin.[13]

Skeena River Watershed First Nations, British Columbia

The Skeena River watershed in north western British Columbia is the homeland of the Tsimshian, Gitxsan, and Wet'suwet'en peoples, as well as the Takla First Nation and Lake Babine Nation.[14] Within the watershed, First Nations people live on and off-reserve. Their land claims are unsettled.

Salmon—principally sockeye—hold particular importance to Skeena River First Nations, both for cultural purposes and as a source of nutritious food.[15] Community members supplement harvested food with store-bought food, and most Skeena River area communities are road accessible all-year. Local food banks in nearby urban centers like Terrace, as well as soup kitchens and school lunch programs also provide key sources of food for many.

Background

First Nations in Canada

The Canadian Constitution recognizes three Indigenous groups—First Nations (referred to in the Constitution as “Indians”), Inuit, and Métis—as “Aboriginal peoples.”[16] More than 1.67 million people in Canada (4.9 percent of the population) identify as First Nations, Inuit, or Métis according to the 2016 Census.[17] This population is the youngest in Canada and was the fastest growing population between 2006 and 2016.[18]

First Nations make up the largest group of Indigenous people in Canada, numbering over 900,000.[19] “First Nations” is a collective term for what is a diverse group of more than 630 communities, representing more than 50 First Nations, and speaking more than 50 languages across Canada.[20]

Before colonization, First Nations occupied large swaths of territory on which they harvested animals and plants for social, political, economic, and cultural purposes as well as for sustenance. However, the Indian Act, a law passed in 1876 and recognized as an instrument to suppress and destroy First Nations’ cultures and economies, sets out the framework of the reserve system, whereby federally-recognized First Nations, known as “bands,” are allotted small parcels of land for their use.[21] Reserves, often in remote areas, were selected without consulting First Nations, and are a fraction of the size of many First Nations’ traditional territories.[22] Almost half (44.2 percent) of First Nations people still live on-reserve, with the vast majority of reserves found in British Columbia, followed by Ontario and Manitoba.[23]

|

First Nations and the Canadian State The Canadian constitution establishes two levels of government: federal and provincial.[24] In 1982, the Canadian constitution was amended to recognize the “existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada,” a set of rights that includes the inherent right of self-government.[25] However, Section 91(24) of the Canadian Constitution also grants the federal government jurisdiction over First Nations, while the Indian Act, along with other federal legislation, controls most aspects of life on-reserve, and continues to impose a paternalistic relationship between the Canadian state and First Nations governments with limited powers delegated from the federal government.[26] While the government of Prime Minister Trudeau has, since 2016, repeatedly committed to establishing a “nation-to-nation, government-to-government” relationship with First Nations, based on recognition of their right to self-determination, including self-government, progress toward realizing this goal has been slow.[27] |

Looming Food Poverty in First Nations

As a direct result of historic marginalization, First Nations face a host of socio-economic inequalities, including inadequate and substandard housing, lack of safe drinking water, and obstacles to accessing healthcare services.[28] The federal government’s main measure of socio-economic well-being, the Community Well-Being Index, has found a substantial gap between the average well-being of First Nations and non-Indigenous communities from 1981 to 2016.[29]

While the majority of Canadians are “food secure,” meaning they have access to food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences, First Nations households are much more likely to face food insecurity.[30] The 2017-2018 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) by Statistics Canada reported that 28.2 percent of Indigenous households off-reserve experienced food insecurity compared to 11.1 percent of white households.[31] The First Nations Regional Health Study, meanwhile, reports that approximately half of First Nations households on-reserve and in Northern communities nationwide were moderately or severely food insecure. Of those households with children, 43.2 percent were classified as food insecure.[32]

Poor Health Outcomes in First Nations

The health outcomes of First Nations tend to be significantly poorer than the average Canadian. Life expectancy at birth is lower by 11.2 years in areas with high concentrations of First Nations compared to areas with low concentrations of Indigenous people.[33] Only 37.8 percent of First Nations adults nationally reported that their health was excellent or very good, while 59 percent of all Canadians rated their health as excellent or very good.[34] A 2018 parliamentary report, for example, found that First Nations people are much more likely to have chronic health conditions at a younger age compared to the general Canadian population and are likely to experience multiple chronic conditions.[35]

Exceptionally high rates of diabetes pose a specific concern for many First Nations populations, with estimated rates three to five times higher among First Nations populations than the general population.[36] The increased rate of diabetes among First Nations is tied, in part, to the erosion of harvesting practices and increased reliance on processed, store-bought foods.[37] Traditional diets are often based on a combination of food sources that provide a protective effect from diabetes.[38]

The health care available in First Nation communities is often limited and of lower quality compared with the care offered to the non-Indigenous population, partly due to inadequate and inequitable government funding.[39] The complexity of overlapping responsibilities between levels of government also contributes to gaps in care.[40]

I. Impacts of the Climate Crisis on First Nations’ Right to Food

Across Canada, climate change is making it increasingly difficult for First Nations to harvest food and live off the land in the ways their families have for generations. As global temperatures rise, there are fewer animals migrating and traditional plants growing on First Nations’ traditional territories. Unpredictable weather patterns and changing climactic conditions, meanwhile, are making harvesting costlier and more dangerous, and sometimes even impossible.

These impacts are projected to worsen as the climate warms. Canada, warming by about twice the global average, is bracing for continued increases in temperatures, more extreme weather, thawing permafrost and reduced snow and ice, and more wildfires, among other changes.

Climate change impacts are also increasing the cost of, and decreasing remote communities’ access to, store-bought foods. The combined impact of diminishing supplies of food for harvest and increasing reliance on less healthy purchased food can have dire consequences for community health and well-being, particularly for those who are already marginalized.

Changes to Canada’s Climate and Physical Environment

Between 1948 and 2016, mean annual temperature increase for all of Canada is estimated at 1.7˚C [3˚F] (roughly twice the mean global warming rate) and 2.3˚C [4.1˚F] for northern Canada (roughly three times the mean global warming rate).[41] Across Canada, the greatest warming has occurred during winter, with a mean temperature increase of 3.3˚C [5.9˚F].[42]

A 2019 report from Environment and Climate Change Canada outlines the consequences of rapid climate change for the country’s future, including more extreme heat, shorter snow and ice cover seasons, thinning glaciers, thawing permafrost, rising sea level, and an increased risk of summer water shortages.[43] Increasing temperatures will intensify some weather extremes, and increase the severity and risk of heat waves, droughts, and wildfires.[44]

Old Crow, Yukon

Community members in Old Crow, Yukon reported warmer temperatures.[45] Robert Bruce, a 70-year-old resident, expressed concern: “I have seen lots of changes [on the land]. It's gotten a lot warmer. Some lakes are drying out.”[46] Annual mean temperature in Old Crow has increased by roughly 1.8°C [3.2°F] from 1950-2013.[47] Warming during winter has been particularly significant across the Yukon, ranging from an increase of 4-6°C [7.2-10.8°F] from 1948 to 2012.[48]

Rising temperatures have been accompanied by decreased snow and ice cover.[49] Community members described what that looks like on their land: thinner ice or lack of ice, rivers freezing later, and snow melting early.[50] Some people recounted dramatic recent changes. Darius Elias, who works for the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation government, observed, “Last year [2018], the river was open year-round for the first time. The amount of times that the river freezes has reduced dramatically.”[51]

Some people in Old Crow also noted, and scientific studies confirm, increasing incidences of unusually deep snow.[52] Snowfall in Yukon is projected to become more variable, with periods of little snow and intense snowfall events likely becoming more common.[53]

Old Crow is also experiencing permafrost degradation, increasing the risk of landslides, ground instability, and draining of lakes.[54] Some community members, like Esau Schafer, who grew up living on the land with his family, also reported an increase of mudslides and riverbank erosion around Old Crow.[55]

Elias told Human Rights Watch that a lake has drained in the area of the Old Crow Flats wetlands where his family has traditionally harvested.[56] The Old Crow Flats have been an essential site for harvesting and cultural practices for centuries, its many lakes supporting diverse species, from migrating birds and caribou, to moose and fish.[57] This area is experiencing significant lake drainage as a result of permafrost thaw and, according to a study, “catastrophic lake drainage” has become more than five times more frequent in recent decades.[58] Elias described the impact of these changes: “When I was a kid I lived on the land from March to June … [but given the dramatic changes in the Old Crow Flats] only a few people still go there.”

Other people Human Rights Watch interviewed in Old Crow also expressed concern about increased forest fires.[59] Robert Bruce, a grandfather from Old Crow who tries to live off traditional food sources because of health reasons, told Human Rights Watch that he worries forest fires may alter the migratory route of caribou.[60] In recent years, fires have burned a larger swathe of territory in Yukon than is usual: in 2019, about 50 percent more area was burned in Yukon than average, while 2017 marked the largest area burned in a decade.[61]

|

Climate Tipping Point: Boreal Forest Three First Nations visited by Human Rights Watch are located within the boreal forest biome, which stretches from Yukon to Newfoundland and Labrador. Like the Amazon, the Canadian boreal is an essential forest system, which serves an important role in storing carbon, and regulating the climate.[62] Fires are a natural part of the boreal renewal cycle, but climate change is putting the boreal forest at risk.[63] About 300 kilometers from Old Crow, in the Yukon Flats region of Alaska, for example, one study found evidence that climate change-enhanced fires have already broken millennia-long ecosystem resiliency due to exceptionally high fire frequency and extent of burning.[64] Canada’s boreal forest may become a net source—instead of a sink—of carbon.[65] |

Skeena River Watershed, British Columbia

Urban localities in the Skeena River watershed have experienced a roughly 1°C increase in annual mean temperature from 1950 to 2013.[66] Across northern British Columbia, winter warming has been particularly significant, ranging from 4-6°C [7.2-10.8°F] from 1948 to 2012.[67]

Community members told Human Rights Watch how these changes are impacting First Nations. Chief Malii (Glen Williams) a Gitanyow Hereditary Chief in the Skeena River watershed said: “We used to have long and cold winters… Really cold, -30 or -40 degrees [Celsius] [-22 or -40°F] at Christmas… Now you sometimes don't see snow until Christmas. We have rains and thunder instead.”[68]

Warmer winters have been accompanied by significant decreases in snow, and dropping water levels.[69] The Skeena River has experienced record lows in recent years, and extreme drought conditions have caused some river channels to dry out completely in late August through October.[70] Warmer winters, decreased snow pack, and reduced glacier meltwater are projected to result in decreasing summer streamflow in British Columbia.[71] Hereditary Chief Malii observed: “We get less snow in the mountains… Hotter summers… Last year were the lowest water levels in 100 years. This year, it is worse.”[72]

Consistent with warming surface air temperatures and lower summer water levels, water temperature is also rising in the Skeena River watershed.[73]

There has also been an increase in forest fire activity in the Skeena River watershed.[74] In northern British Columbia, 2017 and 2018 were record fire years, in part as a result of climate change.[75] Hereditary Chief Ja Dim Ska Nes (Ronnie Matthew West), from the Lake Babine First Nation, said: “We have had many wildfires. This year, [people in my community] were the only ones who were safe in the entire [Babine Lake] area. It was never hot like that in the old days, so we have more fires today.”[76] The risk of large and prolonged fire seasons is projected to increase as temperatures rise.[77]

Attawapiskat and Peawanuck, Ontario

Both Attawapiskat and Peawanuck have experienced a roughly 1.6°C [2.8°F] increase in annual mean temperature from 1950 to 2013, and changing snow and ice conditions.[78]

Community members told Human Rights Watch how ice and snow cover has become thin and unstable, while the time between the winter freeze and spring thaw has shortened.[79] Elder John from Attawapiskat expressed concern about the impacts of warming temperatures on the migratory routes of animals: “The weather is just crazy. Natural law has been broken.”[80]

Abraham Hunter, a councillor from Peawanuck, explained the drastic change in conditions: “We don’t see ice on the Bay anymore. We used to see it in June…The snow disappears in three days now. The water just runs off and does not stay…”[81]

On land, decreased snow and ice cover and shorter frozen periods have been accompanied by permafrost loss.[82]

|

Climate Tipping Point: Permafrost and Peatlands There is a high risk of widespread thawing in northern Ontario, and some models project that the Hudson Bay Lowlands have already surpassed the temperature threshold for maintaining permafrost.[83] Sam Hunter from Peawanuck remarked: “[Y]ou can actually see [the permafrost] thawing and turning into swampland, and trees are dying. Trees that sink right into the muskeg were once four or six feet on dry land.”[84] Permanent permafrost loss could have serious repercussions for the ability of this biome to maintain its significant contribution to global carbon-cycling and climate regulation.[85] |

Climate-Driven Loss of Traditional Food Sources

In recent decades, the percentage of food harvested from traditional sources in Indigenous diets has declined as a result of decreased access to land, loss of harvesting skills, increasing costs or restrictions on hunting and increased access to store-bought foods.[86] However, many First Nations continue to rely on harvested foods as a significant component of their overall diet.[87]

Gitanyow Hereditary Chief Malii told Human Rights Watch, “When we [as the leadership of the for the Gitanyow] did a study in 2010, about 80 percent of our people used traditional food.”[88] He described how his grandfather called the animals and plants that make up their traditional diet “dinner table” in his Indigenous language. He recalled: “[My grandfather] described the moose, berries, and fish like that. He also referred to it as [a] bank.”[89] Hereditary Chief Malii, like many First Nations people Human Rights Watch spoke to, worries that the bank is nearly empty and the impacts will be devastating. This concern reflects the situation in many First Nations.

Changes in Species Availability

Impacts of climate change have altered the availability of First Nations’ traditional food sources in multiple ways. Community members told Human Rights Watch that they observed significant and increasing declines in the quantity of animals and plants available for harvesting due, in part, to changes in the environment they believe are a result of climate change, including changing ice and permafrost, wildfires, warming water temperatures, changes in precipitation and water levels, and unpredictable weather.

Changing Migration Patterns

First Nations members told Human Rights Watch that climate change is impacting the migration patterns of bird species and caribou they harvest.

Community members in Peawanuck described how early and quick snow melts impact the availability of migrating geese, such as snow geese.[90] Mary Jane Wabano said: “If the snow melts, the geese won't fly closer to the community; they used to fly closer when there was lots of snow… Geese go where the snow is.”[91] An Elder in Peawanuck agreed: “We have warm weather in March, all the snow is gone before the geese come and it impacts how they fly. They fly higher and are harder to get.”[92]

Peawanuck community members also said that caribou has become less available due to changing migration routes.[93] Sam Hunter, a hunter and community climate change monitor, says the unpredictability of caribou migration is tied to changing seasonal freeze-thaw cycles: if there’s an early or late freeze up, “[the caribou] won't be walking in their migration route. They'll be walking way out there on the bay or way inland.”[94] Surveys undertaken since 2000 suggest the range of Hudson Bay caribou has shifted eastward.[95] Climate change, which has wrought abrupt ecological change in the region since the 1990s, pushing the southern Hudson Bay area toward a climate “tipping point,” has likely contributed to this shift.[96]

Old Crow residents, meanwhile, worry that climate change-enhanced forest fires are causing caribou to shift migration routes farther from the community, decreasing numbers of caribou physically accessible to harvest.[97] The Porcupine Caribou Herd (PCH) usually passes near the community each spring (April /May) and autumn (August/September).[98] However, recent fires near Old Crow may be altering this pattern.[99] Elizabeth Kyikavichik, a 72-year old childcare worker, told Human Rights Watch: “I am concerned about the caribou. Already now there is less caribou [nearby]... They might have changed the route because of the wildfires.”[100]

Research shows that caribou alter their distributions in response to wildfires.[101] It can take more than 60 years for caribou to return after a fire because of the slow growth of their key-food source, lichens.[102] As the climate continues to warm, increasing the frequency and severity of wildfires, this timeframe may lengthen, risking a severe disturbance of PCH migration patterns.[103]

Reduced and Different Animal Populations

Members of communities reported significant changes in the population of traditionally harvested species in their territories as a result of climate change impacts on habitat.

Moose

First Nations members in the Skeena River watershed in British Columbia are concerned about decreasing moose populations.[104] For example, in the 5,000 km2 Nass Wildlife Area near Terrace, there was a 70 percent reduction in the moose population from 1997 to 2011.[105] While the exact cause of this decline is unclear, it may be tied, in part, to habitat loss caused by climate change-inflated mountain pine beetle infestations and salvage logging of infested forests.[106] Mountain pine beetle infestations are predicted to worsen with climate warming as drought-stressed forests are more vulnerable to infestation.[107]

In British Columbia, warming temperatures are also increasing the risk of moose mortality from winter ticks, a dangerous parasite that previously could not survive the colder climate at northern latitudes.[108]

Caribou

Across Canada, caribou herds are declining due to deterioration of their habitat and increased human disturbance, primarily caused by resource development.[109] Climate change is likely accelerating the decline of some populations as it affects the nutrient composition of caribou food sources, as well as access to food, including important lichens, and calving grounds.[110] Eastern migratory caribou, the type of caribou harvested by members of Peawanuck, for example, were listed as endangered in 2018 due to an 80 percent decline over the past three generations, caused in part by decrease in habitat quality associated with climate change and development.[111]

Caribou are particularly susceptible to climate-driven impacts such as altered forage quality and quantity during summer and winter, increased icing in winter, change in spring timing, and increased summer insect harassment.[112] When their numbers decrease due to mortality, reduced birth rates, or range alteration, it obviously affects the communities who rely on them for food.[113] A 2004 study projects that while warming will likely increase summer food sources for the PCH, other climate change impacts such as increased insect harassment and greater snow depths could result in a herd decline of up to 85 percent in the next 40 years.[114] “[W]ithout the caribou there is no Gwitchin people,” said Elias.[115]

Salmon

Climate change also affects key habitable areas for salmon in Canada, as their river and/or oceans migration, spawning, incubation, and rearing are sensitive to temperature increases and changes in water levels. In simple terms, less hospitable habitable areas for salmon—less salmon. In British Columbia, scientific studies have found that salmon populations have been negatively affected by increasing temperatures in rivers.[116] Many provincial salmon stocks are considered at moderate to high risk of extinction, and further threatened by climate change impacts.[117]

First Nations see less salmon in the Skeena River watershed in British Columbia, a population decline they believe is linked, in part, to warming temperatures.[118] Brian Michell, a fisheries technologist at the Office of the Wet’suwet’en, who monitors fish in the area, said: “The sockeye [salmon] went down from 30,000 in 1990 to 6,000 today... Every year we have been getting less and less... The river and the creeks are warming up to 20 degrees. This year has been the lowest I have ever seen [since monitoring started in 1994].”[119]

Community members from Old Crow also told Human Rights Watch that warming waters have reduced their ability to fish.[120] “We have a problem with our salmon because the [river] water has warmed,” said Robert Bruce from Old Crow. He has diabetes and tries to live off of traditional food sources, but struggles to do so: “It is more difficult to fish. Last year, we did not find any salmon in the river.”[121]

Communities within British Columbia’s Skeena River watershed are also concerned about low water levels, which make it more difficult for salmon to spawn. Hereditary Chief Ja Dim Ska Nes, from Lake Babine First Nation, said: “Salmon is… what we live from… Salmon is food security for us, that is no longer guaranteed.”[122]

Berries and Other Plants

Changing temperatures linked to climate change also affect berries and plants used for food and traditional medicines, often picked by women.[123] For example, climate change will likely cause large shifts in the range and seasonal growth of the huckleberry in British Columbia, which could impact First Nations’ harvests.[124] Some studies connect drier weather with reduced number and size of berries that community members rely on.[125] Berries have also undergone a distributional change in some locations, decreased in others, and been subject to disease in yet others.[126]

Marietta, a junior Elder from Attawapiskat, said: “This summer we did not have strawberries and raspberries. It was too cold. We used to have lots of berries.”[127]

In the Skeena River watershed, where massive wildfires in the past few years resulted in the evacuation of entire communities, the fires have affected traditional berry picking.[128]

New Species

First Nations members interviewed by Human Rights Watch described seeing new, unfamiliar species in their traditional territories. In Peawanuck, Sam Hunter, a community climate monitor, includes garter snakes and mountain lions among the list of new species.[129] Elders in Peawanuck, meanwhile, noted that in addition to warmer water the community is seeing Atlantic salmon and other “big water” fish more common along the Atlantic coast.[130] Warmer weather impacts migratory birds as well. One Elder noted: “We see new species… 15 years ago, pelicans arrived, then turkey vultures came. We have no name for that [in our language] because we’d never seen it before.”[131] Chief Ignace Gull has seen similar changes to migratory birds in Attawapiskat, “water is getting warmer, the ice melts early. Other things—what we see today are pelicans migrating North; cormorants, we see many of them.”[132]

Challenges in Accessing Harvesting Areas

Accessing traditional food sources is based on harvesters’ ability to safely get out on the land in a timely and cost-effective manner, which is affected by changing weather, ice conditions, wildfires, and water levels. In general, climate change is causing more extreme and unpredictable weather patterns that make it more difficult and dangerous for First Nations to access harvesting opportunities. These changes will likely worsen as the climate warms.

Shorter Harvesting Seasons

Community members from Peawanuck and Attawapiskat described how changes in snow and ice conditions have resulted in a reduced period of solid ice and sufficient snow cover necessary to support transport by snowmobile, commonly used to hunt moose and caribou.[133] In Peawanuck, community leadership described a winter where exceptionally early snowmelt resulted in only two weeks of winter hunting, instead of the usual month.[134] In Old Crow, warmer weather has caused a much shorter winter harvesting season in recent years, preventing access to caribou and trap lines for smaller mammals that provide an income for community members.[135]

In the Skeena River watershed, 2018 record forest fires reduced access to harvesting areas.[136] In Burns Lake, British Columbia, Wilf Plasway Junior told Human Rights Watch: “When the fires started they closed off one area where we go fishing. People could not fish to fill up their winter stocks.”[137]

Even where conditions permit travel to harvesting areas, Sam Hunter, a community member from Peawanuck, said changing climatic conditions can impact the success of a harvesting trip: “Sometimes the snow just disappears in two, three days, and... before winter, when it freezes kind of late, sometimes we miss the [hunting] seasons that we used to follow, like caribou hunts, or in the spring goose hunts. Sometimes we can't get anything.”[138]

Dangerous and Difficult Conditions

Climate change has made harvesting more dangerous. Ice thinning can lead to harvesters breaking through the ice, becoming injured and losing equipment.[139] Increased storms, unpredictable weather, and flooding have made harvesting more dangerous.[140] The results in less food harvested to eat for that season; and fewer youth joining hunts, missing out on opportunities to learn harvesting methods.

Margaret Mack, a nurse from Peawanuck who regularly takes her grandkids hunting, said: “We used to know the weather and conditions of the river, and it’s a whole lot different now [… Now] the rivers are dangerous. My brother broke into the ice with a skidoo. It’s gotten unpredictable. The river gets unstable… Spring hunt is dangerous for kids because it is a flood zone.”[141]

Wabano, from Peawanuck, explained: “I only wish that we had the same winter we used to have so we could go hunt. It is difficult for us to go on the land when the spring thaw is too rapid.”[142]

Old Crow residents are also worried about the risks of unstable ice conditions.[143] The changing and unpredictable environment also makes harvesting difficult in the summer. First Nations members from Peawanuck and Old Crow described how unusually shallow and slow rivers make it harder to travel and sometimes prevents community members from going hunting and fishing.[144] Esau Schafer from Old Crow observed the widening of the river because of erosion over the years.[145] He said: “The water spreads and gets wider. It's hard to travel in shallow water with modern boats.”[146]

Increased Financial Costs Related to Climate Change

Increasing costs due to climate impacts can also be a barrier to harvesting: preparing for unpredictable weather requires extra food, gas, and supplies, shifting snow and ice conditions mean altering traditional travel routes, which can result in higher fuel costs and longer travel times, while shifting migration patterns increase the likelihood of needing to undertake multiple trips.[147]

In general, harvesting is expensive, requiring equipment, transportation, fuel, and food for the time hunting, trapping, or fishing. Peawanuck community member and hunter, Sam Hunter, explained: “Especially when we don't get anything, it's expensive…With gas and grub… it's like, CAD$1000 a time. And if you keep going out, if you don't get anything, it adds up.”[148] In Attawapiskat, for example, 40 percent of households that harvest spend over half of their income on harvesting.[149]

As community members need to spend longer periods of time to harvest species that are further away or in unfamiliar locations, the cost of harvesting also extends to lost work and school time.[150] Georgina Wabano, from Peawanuck, described how the time needed to secure an adequate harvest is increasing, requiring the additional expense of multiple or longer trips: “When I hear my grandparents talking, they say, when they used to go hunting, there was such an abundance of food. Like, … you would only hunt like a day or two. And then you would have what you needed to feed your family. Nowadays you will have people that will go out, all spring. They leave by Ski-Doo, and they end up coming home by boat. So, about a month, they're … hunting daily to get what they need.”[151]

Limited Alternatives to Traditional Food Sources

The impacts of climate change on First Nations’ ability to access traditional foods are compounded by the limited availability of affordable, nutritious alternatives.

Transported foods—the main supplement to traditional harvested foods—have historically been disproportionately expensive in remote and northern communities due to in part to high operating costs.[152] To reach northern and remote communities, food sourced in the south must be transported over vast distances, past the reach of all-season roads and rail, requiring expensive, weather-dependent transport by air, sea, or seasonal winter roads, dramatically increasing food costs.[153]

The high costs of transport particularly impact access to nutritious food, especially produce. Fruits and vegetables (fresh, frozen, and canned) are more expensive than low-nutrient, processed store-bought foods (foods high in sugar, fat, and starch, like cereal, grains, potato chips, and candy) in northern markets, often by several orders of magnitude.[154] Some of this price differential can be attributed to increased transport costs for fruits and vegetables, which are generally more susceptible to spoilage during shipment, have shorter shelf lives, and require a controlled temperature during shipment and storage,[155] while less nutritious foods like cereal, grains, potato chips, and candy are typically dry, resist spoilage, and have stable shelf lives.[156]

Sometimes foods are spoiled by the time they reach communities.[157] In one survey of northern First Nations, 82 percent of respondents stated their store often or sometimes sold expired food, while 57 percent said that perishable food was not usually in good condition.[158] Kyle Linklater, a community member from Peawanuck said: “[Vegetables] don't last too long. And by the time we get them, they're either rotten or just about to be.”[159]

In remote communities visited by Human Rights Watch, families spend a significantly larger percentage of their income to secure healthy and nutritious food than they would in southern or urban locations.[160] In Old Crow, a family of four spends roughly 41 percent of their monthly budget to eat a healthy diet.[161] In Yukon’s capital, Whitehorse, by contrast, a family would only need to spend 17.5 percent of their monthly budget on the same diet.[162] In Attawapiskat and Peawanuck, a family of four would spend almost half their monthly budget for food (47 percent in Attawapiskat; 45.8 percent in Peawanuck).[163] The same family’s food budget would go twice as far in Toronto, where a family of four spends 17.4 percent of their monthly budget on healthy food.[164] Families whose income falls below the median income reported in each community would have to allocate even more of their monthly budget to secure a healthy diet from store-bought food.

Climate change will further increase the cost of imported nutritious food options. According to one report, climate change impacts on agriculture contributed to an over 17 percent increase in the cost of vegetables in Canada in 2019.[165] As the agricultural sector continues to face climate change impacts such as unpredictable crop yields, heat-wave livestock threats, pasture availability and pest and disease outbreaks, costs will continue to rise.[166] Overall, “annual food expenditure for the average Canadian family is predicted to rise by $487 in 2020.”[167] These price hikes will be felt much more intensely in northern and remote communities where food costs, particularly the cost of produce, is already a barrier to healthy eating.

Climate change and transport costs are not the only drivers of high food costs in northern markets. Research suggests that limited retail competition in small, remote communities may also play a role.[168] The Northern Store operator, The North West Company (NWC), a for-profit company traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange, is the only grocery store in 54 percent of communities in the territories and provincial Norths that do not have year-round road access.[169] In communications with Human Rights Watch, NWC said that while it may not face on-the-ground retail competition, it competes with customers “out-shopping” in major regional centres when they leave their home communities for vacation, business, or medical reasons.[170]

Some community members have criticized NWC for failing to provide affordable healthy, nutritious food options.[171] As Mack explained, a system that is dominated by one retailer raises concerns about limited health options: “Northern [Store] controls what you eat.”[172] Retailers in northern markets have limited incentive to stock nutrient dense, but perishable fresh produce due to the high cost of transport, and risk of spoilage.[173] The North West Company’s website does note a 20 percent increase in sales since 2017 from Health Happy, a program that makes lower sugar, salt, fat, and caffeine content food products more accessible in remote communities, but the company told Human Rights Watch that the demand for these products remains limited.[174]

In 2019, NWC set a three-year commitment to “invest in lower food pricing” in stores in northern Canada.[175] The company attributes increased sales in northern Canadian stores 2020 in part to lower food prices.[176]

In order to have more control over their food supply, some communities operate their own grocery stores. Old Crow, for example, decided not to renew operating contracts with the NWC, instead, turning to the Arctic Co-operatives Ltd., a co-operative federation owned and controlled by 32 community-based co-operative business enterprises located in Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, and Yukon.[177] But the Co-op faces the same logistical challenges as NWC, and according to some interviewees, cost and limited selection of fresh produce remains an issue.[178] Councillor Esau Schafer told Human Rights Watch: “Even though the community now owns the store, many don't find food they can afford.”[179] Tracy Rispin, the store manager in Old Crow, said: “We get criticized a lot and visitors take pictures of the price tags. But groceries are flown in from Edmonton or Calgary [which makes them expensive].”[180]

Another option for households to buy healthier, affordable food is to order it from southern stores. While individual orders may offer access to more variety of foods than are available in community, they still face the challenge and cost of long-distance transport, and without the added savings that retailers secure through bulk orders. Further, while a limited number of registered retailers offer a variety of purchase methods, ordering food often requires a credit card—which can be a barrier for some low-income families.[181] Community members without bank accounts or credit history face significant challenges in accessing credit.[182] In general, First Nations members are underserved by financial institutions and are more likely to be unbanked.[183] For remote communities, travel to financial institutions in urban centers to open an account can be a barrier.[184]

Climate Change Increasing Food Transport Costs: Winter Roads

The already high costs of imported foods in northern and remote communities are increasing further due to warming temperatures, resulting in later freeze-up and earlier thaw, thereby shortening the winter road season. Built seasonally over frozen land and water, winter roads are constructed out of compounded snow and ice that is regularly flooded and frozen until it reaches the required thickness to support transport.[185] In Ontario alone, there are more than 3000 kilometers of winter roads, built and maintained by 29 First Nations and one municipality with financial and technical backing from provincial and federal governments.[186] The cost of building and maintaining winter roads is significant, but still much less than permanent roads.[187]

Winter roads are essential to remote and northern First Nations to deliver supplies, access traditional foods; maintain social networks through social and cultural events; and to access basic social services such as health care.[188] They are essential in lowering cost of living, including food costs.[189]

Winter roads are dependent on weather patterns that are becoming increasingly variable due to climate change.[190] Winter road construction requires sub-zero temperatures and little snow to form a frozen base, followed by enough snow to compact into adequate road thickness and build crossings over water.[191] If temperatures rise above freezing during the winter road season, it risks eroding or weakening.[192]

In recent years, winter road seasons have been increasingly unreliable. For example, the 2019-2020 winter road season started as much as two weeks late for some northern Ontario First Nations, with some communities only being able to transport partial loads because of inadequate ice thickness.[193] The quality of winter roads is also increasingly variable, limiting the weight of vehicles that can safely travel the roads and decreasing the frequency with which transport can bring supplies to remote communities.[194] In Attawapiskat, then Chief Ignace Gull told Human Rights Watch: “[Winter road season] is only two months now, previously it was December to April…The road is a lifeline for people to visit family. They use it to buy bulk shopping.”[195]

In Ontario, government and independent reports have projected increasingly limited windows of operation for winter roads.[196] A 2014 report by consulting firm Deloitte, for example, projected that operating windows for winter roads serving Ontario’s central and northern First Nations’ communities would decline 12 to 20 percent by 2050, and 20 to 40 percent by 2100.[197]

Impact of Increasing Food Poverty on First Nations Health and Culture

Existing inequalities facing First Nations, combined with climate impacts on access to food have adversely affected their health and culture. Community members described having to skip meals or purchase less healthy, but more affordable food in local stores to supplement inadequate supplies of traditional food. These coping mechanisms are associated with serious health concerns, especially for older people, children, and those with chronic illnesses. The impact on cultural identity associated with loss of traditional food also imposes a toll on physical and mental health at both an individual and community level.

Negative Health Outcomes

Studies have shown that loss of traditional food and related harvesting practices, along with increased reliance on processed, lower-nutrient imported foods is tied to increased negative health outcomes in northern and remote communities, such as increased chronic diseases, and in particular, higher rates of obesity and diabetes, including among First Nations children.[198]

One Elder from Peawanuck explained: “We survive only on wild food. If the season is bad, we have to rely on the store, and it is not very good. I suspect that’s where all the diabetes come from… in 1950, there were no known cases of diabetes. The average person in 1950s would only go to the store three times a year, [and] otherwise lived off the land.”[199]

Now, climate-exacerbated food poverty is adding to these risks: increasingly requiring community members to skip meals or buy more low-nutrient store-bought food.[200] Older people interviewed for this report, for example, have cut down the number of meals they eat daily as sourcing traditional food becomes more difficult. One 77-year-old Elder from Old Crow who typically hunts for caribou and traps during winter months, said: “This year it was hard for us to go to the land because there was not much snow. . . [which means] not eating very much. I only eat one meal per day.”[201]

Skipping meals is particularly dangerous for people with type 2 diabetes, which is present in elevated rates among First Nations people.[202] One study found that among older adults with type 2 diabetes, those diagnosed with malnutrition are nearly 70 percent more likely to die of any cause versus those without diagnosed nutrition deficiencies.[203] This study takes on a particular urgency and concern in the context of the global Covid-19 pandemic, where pre-existing conditions such as diabetes have been associated with increased severity of the disease and risk of mortality, and as Covid-19 is causing delays and interruptions to food production and transport, making for even less reliable access to nutritious food in remote communities.[204]

As climate impacts increasingly reduce availability of and access to traditional foods, skipping meals will likely be an increasingly common tactic given the high costs of purchased foods. A nurse in Peawanuck explained, “our diet is geese. You have to get as much as you can. You have to plan out your food. It has to last until the geese arrive [again]... I have an elderly mother, we provide for her. To supplement [with store food] is very expensive.”[205] Research carried out in Ontario First Nations indicates that 32 percent of households worry that their traditional food supplies would run out before they could get more.[206]

Adults often hide hunger, so when families face food shortages at home it is most visible to educators and school administrators when children go to school. In several First Nations Human Rights Watch visited, teachers reported that some children do not get enough food at home.[207] Social stigma surrounding poverty and fears related to the removal of First Nations children from their families by social services for poverty related reasons influence how these issues are managed.[208] Elias from Old Crow said: “[I]f people do not have enough, they will not admit it. They are proud.”[209] Roger, a councillor from Attawapiskat, said: “People go hungry, but don’t show it.”[210]

Some studies suggest that malnutrition at an early age may increase risks of developing Type 2 diabetes.[211] While diabetes tends to be present in individuals 50 years and older, it has been appearing earlier and at increasing rates among First Nations children.[212]

In road-accessible communities, low income families often rely on food banks to make up for the challenges of obtaining traditional foods.[213] Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chief Na'Moks (John Risdale), from the Skeena River watershed, said: “Low income families go to the food bank when we should be going out to the territories. When we were growing up we never thought we'd need a food bank.”[214] For remote communities, food banks are not common.[215]

School food programs offer another support for families. One counsellor from Old Crow put it simply, “Some kids go hungry to school….”[216] A teacher in Smithers, British Columbia said: “There is a lot of kids who do not eat on the weekends. We have programs here where kids take food home for the weekend. Lots of schools have lunch-programs but they do not offer traditional food.”[217]

Loss of traditional food also impacts what community members purchase for food. Tracy Rispin, Co-op store manager in Old Crow, observed: “People buy differently when they have traditional food. Not having the caribou is devastating.”[218] For instance, studies show that some First Nations’ people tend to stock up on less expensive dry foods (like rice and pasta) when it is cheaper, changing nutrition intake.[219] One study of First Nations in British Columbia found that eating traditional foods was associated with a decreased intake of ultra-processed foods.[220]

First Nations older people and people with chronic diseases are particularly vulnerable to the health implications of food poverty making it imperative to eat a healthy diet. For many First Nations older people, access to traditional food is an essential part of eating healthy. Medical providers interviewed by Human Rights Watch expressed concern that people with chronic diseases such as diabetes do not follow the recommended diet for cost reasons.[221] A 58-year-old Elder from Peawanuck who has lost his vision and lives off disability benefits said: “We cannot eat vegetables, they are too expensive. We buy ground beef, milk and cereals at the store.”[222]

Parents struggling to provide food for their children are also sometimes left with few options beyond cheaper, less healthy, imported foods. An educator in Peawanuck said: “kids are impacted by poor food options...teeth are rotting out of their mouth.”[223] First Nations children in Yukon obtain over 90 percent of their dietary intake from grains and other foods high in sugar and fat, creating a high risk for chronic disease such as diabetes and heart disease.[224]

Climate-induced food insecurity adds to an already significant mental health crisis facing many First Nations as a result of historical and intergenerational trauma, discriminatory government policies, enforced separation of children from families and communities, insufficient access to mental health care and psychosocial support, and more.[225] Indigenous people die by suicide at a rate three times higher than non-Indigenous people.[226]

|

Impact of Canada’s Historic First Nations Polices on Culture, Food, and Health Canada’s long history of assimilationist government policies and practices have eroded, and at times expressly prohibited, First Nations cultural traditions, taken First Nations children away from their communities, and systematically marginalized First Nations people to this day.[227] The Indian Residential School System, which spanned the 1870s through 1996, offers one stark example of how Canada’s assimilationist approach to First Nations populations has had long-term impacts on their well-being, food poverty, and health. The Canadian government oversaw the forced removal of over 150,000 Indigenous children to residential schools explicitly intended to break the cultural ties between Indigenous children and their communities.[228] At these schools, children were subject to egregious verbal, physical, and sexual violence.[229] Food poverty played a significant role in the trauma and negative impacts of residential schools. Children taken from their home community and traditional lands were deprived of access to traditional food, and the ability to harvest. As one residential survivor told the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was established in 2008 to document impacts of the residential school system on survivors, “the people that went back [to their home communities] had to relearn how to survive. And at that time, survival was fishing, hunting, and trapping.”[230] Mack from Peawanuck explained to Human Rights Watch: “I went to Fort Albany to residential school. We were taken away from our traditional life. We never left that building. We did not come home for Christmas. We were always confined to that building. We only went outside for half an hour [a day]. When we came back as teenagers, we needed to learn how to live off the land.”[231] At residential schools, prolonged hunger and malnutrition were a common occurrence.[232] According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the “government knowingly chose not … to ensure that kitchens and dining rooms were properly equipped... and, most significantly, that food was purchased in sufficient quantity and quality for growing children.”[233] Students were forced to consume spoiled or rotten food, and even, in some instances, forced to eat their own vomit.[234] This program of neglect and abuse has had long-term, generational health implications for First Nations in Canada, and studies have found that physical health outcomes of survivors and their descendants, such as increased risk of obesity and diabetes, are almost certainly tied to prolonged malnutrition experienced by residential school students.[235] |

Negative Impacts on First Nations Cultures

The centrality of traditional food and going out on the land to First Nations cultures means that climate change is threatening not only the food supply, but also the land-based knowledge systems related to it, and ultimately the very identity and socio-cultural fabric of First Nations.

|