In 2016, more than 33,000 people died from accidental drug overdoses involving opioids such as prescription pain medications, heroin, and fentanyl – a powerful synthetic opioid. The US Centers for Disease Control have called these deaths an “epidemic.” Since 2000, drug overdose deaths have increased 137 percent, with deaths involving opioids increasing 200 percent during that period. The toll is highest in rural America, where rates of death from opioid overdose are far higher than in metropolitan areas.

Overdoses involving opioids can be effectively reversed if the medication naloxone is administered shortly after it occurs. Naloxone, a safe and generic medication, can be administered by non-medical personnel with minimal training. Between 2010 and 2014, at least 30,000 overdoses were reversed with the medication, in most cases by people who use drugs themselves who were at the scene. However, naloxone is only effective if someone who witnesses the overdose administers it or immediately calls emergency services.

Human Rights Watch documented the cases of Michelle Hamby, 49, a mother from Arizona, and Kendra Williams, 23, a nursing student from North Carolina, which show how naloxone access can be the difference between death and a second chance at life.

Michelle, who has lost two children to heroin overdose, found her daughter Breana passed out on the bathroom floor. She called paramedics, but they did not arrive for more than 10 minutes, and by then it was too late. Michelle believes that if she had naloxone available she might have saved Breana’s life.

Kendra was, in her words, “a full-blown addict” by age 15. Naloxone saved her life after an overdose, and she now is off heroin, in school, and is raising a child with her fiancé. Kendra and Michelle both volunteer at local groups that provide naloxone to people who use drugs along with clean needles, health care information, and testing for HIV and hepatitis C.

The report documents numerous obstacles to accessing naloxone, including the absence of “good Samaritan” laws; laws barring or limiting syringe exchange and harm reduction programs that offer naloxone; and high prices for the medication.

People witnessing an overdose are often reluctant to call 911 due to fear of prosecution under state drug laws. “Good Samaritan” laws protect people who call emergency services to the scene of an overdose from prosecution, but 14 states don’t have them, leaving people risking arrest for saving someone’s life.

Police are often the first to respond to an overdose incident, especially in rural areas. More than 1,200 police departments now carry naloxone, but that is still a small fraction of agencies in the US. Federal leadership is needed to promote proven, public health approaches to the opioid crisis, but signs that the Department of Justice intends to toughen drug law enforcement and sentencing raise concerns that people who use drugs will be driven underground and away from health and harm reduction services that can save their lives.

“More police need to be trained and equipped to reverse overdoses with naloxone,” said McLemore, “but a return to the ‘war on drugs’ will result in fewer calls to 911, and lives will be lost."

A review of state laws regarding access to naloxone and syringe exchange contrasts states such as North Carolina, where widespread access to naloxone has resulted in 6,000 overdose reversals since 2013, and Kansas, a state with no “good Samaritan” laws or other laws designed to increase access to naloxone, and where syringe exchange is prohibited under criminal laws. Nearly 1,000 people died of overdose in Kansas between 2013 and 2015.

Syringe exchanges are explicitly authorized in only 21 states and the District of Columbia. In other states, drug paraphernalia and possession laws restrict the operation of syringe exchanges despite decades of evidence that these programs do not increase drug use or crime but instead serve as gateways to treatment for drug dependence and reduce transmission of HIV, hepatitis, and other blood-borne diseases. Rural areas in states such as West Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky, where the opioid crisis is most acute, have a particular shortage of syringe exchanges, which are a primary site for delivery of naloxone to people who use drugs.

Programs such as the IDEA Exchange at the University of Miami in Miami, Florida deliver a range of health services, referrals to treatment, and screening for infectious disease. Between 2013 and 2015, 8,336 Floridians died of drug overdose, and there appears to be no end in sight. In 2015, the rate of death from overdose in Florida rose 22 percent, one of the highest increases in the nation. Named after the state’s Infectious Disease Elimination Act, the IDEA Exchange opened in December 2016 and in a few short months has provided services for more than 200 clients; removed 20,000 dirty needles from the streets in exchange for clean ones; conducted nearly 200 tests for HIV and Hepatitis C; and connected more than 20 people to drug treatment programs. In March of this year, the IDEA Exchange began distributing naloxone. Yet it is the only public syringe exchange in the state, as criminal laws in Florida impede expansion of these vital programs.

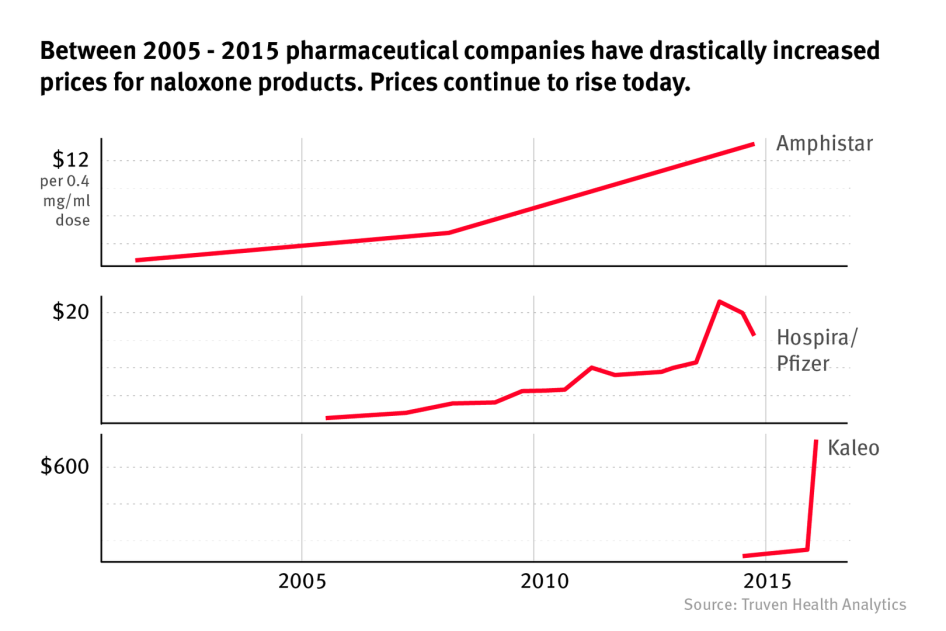

Naloxone prices have increased dramatically in the past decade, creating another barrier for individuals, community groups, and public health and law enforcement agencies to distribute the medication. Naloxone could be bought for under US$1 in 2005 but now ranges in cost from US$20 to US$4,500, depending on the form, dose, and manufacturer.

Naloxone is covered by many insurance plans, including Medicaid, but experts say that giving it “over-the-counter” status would be a game-changer for people dependent on opioids. With its 30-year track record of safety and efficacy, the US Food and Drug Administration should work with drug manufacturers to promote the transition and make naloxone available in vending machines, convenience stores, and similar locations.

In the meantime, preserving insurance coverage for naloxone and for health services for people who use drugs is vital. Efforts to weaken the Affordable Care Act threaten to undermine this goal, as 1.2 million people in the US have accessed drug dependence treatment from Medicaid expansion alone.

“The Trump administration and state governments have a choice: help to save lives by making Naloxone more accessible, or let thousands more die needlessly on their watch,” McLemore said.