Prologue

Breana and Chandler: Siblings Lost

Having to bury your own child is a parent’s worst nightmare. Michelle, a 49-year-old former account executive at American Express from Peoria, Arizona, has done it twice—because of heroin.

Michelle’s daughter, Breana, became dependent on prescription painkillers when she was 19 and later switched to intravenous heroin use. She died in March 2013, aged 25. Michelle said:

It was an ordinary day. She just went into her bedroom to take a nap. I [later] found her passed out, a needle sticking in her arm. I did CPR and called 911 but it took 10 minutes for them to arrive.

Yet the outcome could have been different if Michelle had had access to naloxone—a safe, easily administered medication that, if given in time, can reverse an overdose. “If I had had naloxone, maybe I could have saved her. I anguish over that every day,” Michelle said.

Three years later, Michelle’s son, Chandler, 25, also died. Like Breana, he had struggled with drug dependence although appeared to be doing well: he had been through treatment for heroin dependence and worked at a rehabilitation center in Prescott, Arizona. He died of an overdose on what would have been Breana’s birthday, shortly after the family had gathered for a memorial ceremony for her. Michelle believes Chandler’s grief over Breana’s death, triggered by the memorial, contributed to his relapse.

Michelle has tried to use her grief as a force for good. She left her job; she now devotes much of her time advocating for harm reduction services in her town and in the state of Arizona, hoping she can save others from the tragedies she has endured.[1]

Kendra: A Second Chance

Kendra, 23, grew up in Wilmington, North Carolina. In middle school, she struggled with anxiety and depression, for which she was prescribed Xanax. Almost immediately, she began taking more than prescribed. In high school, she tried heroin. It was “love at first use,” she told Human Rights Watch. By age 15, she was what she calls a “full blown heroin addict.” At the same time, her mother suffered from chronic pain and became dependent on pain medication as well as medications for anxiety and depression. When Kendra was 16, her mother ran out of her pain medication, bought some methadone on the street, and died of an overdose.

“Some people would use that as a reason to get clean, but I was the exact opposite,” Kendra said. “I really spiraled downhill after that.” She was, as she put it, “kicked out of the house” and stopped going to school. She preferred not to talk about how she got money to support her habit.

Kendra overdosed numerous times: “More … than I can count.” Each time, she said, she was lucky enough to have someone there who had naloxone and brought her back to life.

One day, Kendra went to the emergency room because she felt sicker than she ever had before. A nurse told her that she was pregnant. Kendra described that as a life-changing moment:

They gave me an ultrasound, and I saw this baby that already had arms and legs and features. It was like getting slapped in the face with reality: this is not about you [alone] anymore. There is a human being inside of you that is completely relying on you for everything…. I knew that something had to change 'cause I couldn't keep living like that.

With the help of her father and her boyfriend, who himself was trying to stop using heroin, she went to a local drug treatment facility that had a program for pregnant women. They successfully enrolled her in a methadone program.

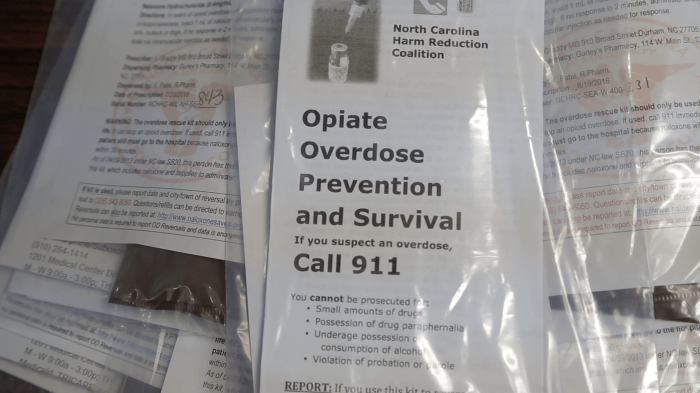

Today, Kendra and her boyfriend, now her fiancé, no longer use drugs, and are raising a healthy son together. Kendra is back in school, training to become a nurse. She also volunteers with the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition and helps other people who struggle with drug use problems avoid overdose and infectious disease. She always carries naloxone with her and has personally reversed at least 25 overdoses because people know to call her when one occurs.

Describing an overdose in February 2016 in her home town, she said: “This guy is cold, his lips are blue, this guy isn’t breathing, there’s no pulse.” She gave him a shot of naloxone: “As soon as I felt that pulse, a wave of relief washed over me. He’s going to be ok.” She had given him a second chance.[2]

Summary

In 2015, 52,404 people in the United States died of a drug overdose, more than any previous year on record. Some 33,000—63 percent—of these deaths involved opioids, including heroin and prescription pain medicines.

Most people who died of overdoses involving opioids were white and male, though deaths among women are increasing at an alarming rate. Since 2000, drug overdose deaths have increased 137 percent; deaths involving opioids have increased 200 percent. The human impact of what the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has called an “epidemic” of overdose involving opioids is enormous, affecting tens of thousands of individuals and families. The toll is highest in rural America, where rates of death from opioid overdose are far higher than in metropolitan areas.

In some towns, accidental overdoses have overwhelmed emergency services, as in Louisville, Kentucky, where officials received 52 overdose calls in 32 hours in February of this year. Many involved heroin mixed with fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid.

Amid these high rates of overdose deaths, overdose prevention and access to the medication naloxone are critical lifelines. A safe, generic medication, naloxone can essentially bring someone back to life if given in the early stages of an overdose. Moreover, it can be administered by non-medical personnel with minimal training. Between 1996 and 2014, naloxone reversed at least 30,000 overdoses; the real number is probably higher as many cases go unreported.

For overdose prevention to be effective, however, it is essential that the people who are likely to be first at the scene of the overdose—generally family members, other people who use drugs or prescription pain medicines, and uniformed first responders—have naloxone on them and know how to use it.

Given the extraordinary numbers of people in the US who are falling victim to accidental overdoses, federal and state governments should take proactive steps to enable overdose reversals. This report explores the measures that are required to put in place an effective program to prevent overdose deaths and the challenges that need to be overcome to ensure that as many lives can be saved as possible. These include:

- Ensuring people who use drugs have naloxone and know how to prevent or reverse overdoses and have the means to do so. People who use drugs are critical to any effective overdose prevention program, as they are often present when an overdose happens and so best situated to save the victim’s life.

- In 2013, 82 percent of overdose reversals were performed by drug users helping a friend, companion, or acquaintance, according to one nationwide study. Harm reduction programs—services that meet people who use drugs “where they are” and are directed at reducing the potential harms of drug use—provide a safe environment for people who use drugs and are therefore a key place to distribute naloxone and teach people how to use it.

- Prescription rule reforms. Traditionally, naloxone has been a medicine that could only be dispensed with a prescription from a physician for a specific individual. This is not a workable arrangement in the case of accidental overdoses. This severely impedes the wide distribution of the medicine to people who use drugs, their family, and community members.

- It is therefore essential that prescription rules be changed to allow so-called third-party prescriptions and standing-orders that permit the medicine to be distributed to people a doctor has not directly examined (such as community organizations) or, more effectively, to designate naloxone as an “over-the-counter” medication that can be issued without prescription.

- Encourage reporting of overdoses. Emergency service personnel can only reverse overdoses if they are called to the scene without undue delay. As possession and use of drugs remains a criminal offense in the US, people who witness overdoses may be reluctant to call 911. This puts them in the impossible situation of choosing between exposing themselves to criminal charges or saving a life. States must adopt laws that protect people who report overdoses from criminal prosecution.

- Equipping law enforcement and emergency services. Law enforcement officials are often among the first on the scene of an overdose, but if they do not carry naloxone, the overdose victim may die anyway. Traditionally, only emergency medical personnel carried naloxone and were trained in administering it. All first responders should carry naloxone and know how to use it.

The Opioid Crisis and the Trump Administration

President Donald Trump is clearly aware of the opioid crisis in America; much of the prescription drug use as well as the most alarming rates of death from overdose are centered in rural counties that formed the backbone of his electoral support. He has vowed to address the problem, telling Congress that “our terrible drug epidemic will slow down, and ultimately stop.” He told Congress: “We will stop the drugs from pouring into our country and poisoning our youth, and we will expand treatment for those who have become so badly addicted.”[3]

The Trump administration’s budget proposal calls for US$500 million for treatment expansion, but it is unclear whether that is new funding or money previously appropriated under the 21st Century Cures Act. Trump issued an executive order announcing a commission to study the problem, but it is also not clear whether this will build upon work already reflected in a comprehensive 2016 report by the US Surgeon General, or prove largely redundant.

In a speech to law enforcement leaders on March 15, 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions made clear that he plans to significantly ramp up federal enforcement of laws targeting drug traffickers. Sessions did not mention increased enforcement of laws for simple drug use and possession, but scant reference to treatment and prevention in the speech raises concerns that the Trump administration may return to the failed policies of the “war on drugs”—emphasizing criminalization over health approaches—which have proved disastrous to individuals, families, and communities as well as to respect for human rights.

Currently, more people are arrested on drug charges than for any other offense, and rates of arrest are increasing. Instead of drawing people who use drugs toward potentially life-saving health and emergency services, policies that emphasize criminalization push them away.

The GOP health care reform plan, which the president supported, would have set back expansion of drug treatment that is currently underway by abolishing the parity of physical and mental health care for insurers established under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), allowing insurance providers to stop covering mental health services, including drug dependence treatment.

The GOP plan called for phasing out Medicaid expansion, which provides coverage to millions of working class people who struggle with drug use in states such as Ohio, West Virginia, Kentucky, and other states where rates of overdose are among the highest in the nation. The GOP’s effort to repeal the ACA failed, but the inclusion of these provisions in future legislation would significantly undermine access to health care and drug dependence treatment.

In recent years, the federal and many state governments have taken steps to improve overdose prevention, making significant progress in some of the above areas. Forty-six states now allow third-party prescriptions or standing orders for naloxone so that individual prescriptions are not necessary. This allows public health departments, law enforcement, emergency services, community groups, and individuals greater access to naloxone. In addition, 36 states and the District of Columbia have adopted overdose Good Samaritan laws that exempt people who call in overdoses from prosecution.

At the federal level, the Obama administration promoted access to naloxone as part of a larger strategy to respond to the national crisis of increased opioid use and death from overdose. Through its Office of National Drug Control Policy, it promoted and coordinated a multi-tiered approach that included efforts to reduce both supply of and demand for drugs, combining elements of law enforcement and public health. Moreover, the ACA extended health insurance to millions of people and made it mandatory for insurance providers to cover mental health care, lowering the barrier to getting drug dependence treatment.

While this strategy made some important progress, the Trump administration faces major challenges if it wants to significantly reduce overdose deaths.

The federal government and many states continue to restrict comprehensive harm reduction programs, despite overwhelming evidence that providing clean syringes and other harm reduction services have significant positive outcomes and do not increase drug use or crime. Federal money is available to support syringe access programs and for naloxone purchase and training, yet some states are not taking advantage of these funding opportunities, and there is a significant shortage of harm reduction programs in rural areas where most deaths from overdose are occurring.

In Kansas, for example, deaths from overdose among 12 to 25-year-olds quadrupled in the last decade. Between 2013 and 2015, 992 people died of drug overdose there, and four counties were identified by the CDC as being at high risk of severe HIV outbreak due, in part, to high rates of injection drug use. Yet Kansas has no laws that promote naloxone access, no Good Samaritan laws that protect those who call in overdoses from prosecution, syringe exchange programs are illegal, and syringes are criminalized under drug paraphernalia laws.

As noted, naloxone’s status as a prescription rather than an “over-the-counter” medication creates a significant barrier to expanded access. Moreover, using a prescription medication without a physician’s prescription may trigger liability, which prevent many state agencies—including law enforcement and emergency service providers—from carrying naloxone. While 36 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws to exempt naloxone from such liability, changing state legislation can be difficult.

In states like North Carolina, for example, that have achieved widespread access to naloxone, approximately 140 sheriffs or police departments carry the medication. However, that represents only one-fifth of the law enforcement agencies in the state, and in several counties with very high rates of overdose the local police do not carry naloxone.

Moreover, the federal government has also taken little action to date to ensure the continued affordability of naloxone, a significant barrier to overdose prevention programs. While in 2005 naloxone cost less than $1 per dose, price increases by manufactures in recent years have resulted in prices that now range from $20-$4,500 per dose depending on the format, making it unaffordable to many community organizations, harm reduction programs, and law enforcement agencies without subsidies or additional funding.

Federal officials have expressed concern over these price increases but have not acted to counter them. Even if every state took necessary legal steps to remove barriers to naloxone distribution, the cost of the medicine remains prohibitive for those who need it the most. On the campaign trail, Trump promised to tackle high drug prices by increasing government leverage in price negotiations. As president, he has met with pharmaceutical companies and has backed away from this concept, calling it “price-fixing.”

***

Accessibility and affordability of essential medicines, such as naloxone, are an essential component of the right to health. To achieve the goal of ending the opioid crisis in the US, President Trump should continue, and expand, the health initiatives started by the Obama administration.

The Trump administration and state governments should increase, not erode, emphasis on public health approaches, both through prevention and by ensuring accidental overdose deaths can be reversed. They should ensure that people who use opioids, whether for medical or non-medical reasons, have access to adequate information about the risks of overdoses and the steps they can take to prevent them. And they need to ensure that those likely to be at the scene of an overdose first—people who use drugs—have access to naloxone so more overdoses can be reversed.

Recommendations

To the US Congress

- Oppose repeal or replacement proposals for the ACA that fail to maintain key provisions that promote access to health care for people who use drugs, including expansion of insurance coverage and the parity requirement for mental health coverage, behavioral health, and treatment for drug dependence.

- Support comprehensive harm reduction programs that include access to clean syringes; HIV and hepatitis C prevention information; drug dependence treatment; overdose prevention information; and naloxone. Support states to repeal criminal laws that prohibit or inhibit access to syringe exchange programs.

- Ensure that state, county, and city health and behavioral health agencies as well as law enforcement and emergency medical services have the training, funding, and other resources to increase access to naloxone in local communities.

- Take steps to ensure affordability of naloxone for overdose prevention, as recommended by the World Health Organization, the Fair Pricing Coalition, and other public health experts.

- Oppose reinstatement of the failed policies of the “war on drugs.” Instead, support responses to drug use and to people who use drugs that emphasize public health and respect for human rights rather than criminalization, increased policing, and harsher sentencing.

- End the criminalization of personal use of drugs and of possession of drugs for personal use.

To States

- Support access to health care for people who use drugs, including comprehensive harm reduction programs that include access to clean syringes; HIV and hepatitis C prevention information; drug dependence treatment; overdose prevention information; and naloxone. Take advantage of federal funding opportunities to increase capacity for these programs.

- Repeal laws that prohibit or inhibit access to syringe exchange programs.

- Pass enabling legislation for increased access to naloxone, including standing orders and Good Samaritan laws that protect users and bystanders from arrest, charge, and prosecution, as well as people on probation and parole.

- Ensure that state, county, and city health and behavioral health agencies as well as law enforcement and emergency medical services have the training, funding, and other resources to increase access to naloxone in local communities.

- Provide Medicaid coverage for “take-home” naloxone.

- End the criminalization of personal use of drugs and of possession of drugs for personal use.

To the Food and Drug Administration

- Promote the transition of naloxone to “over-the-counter” status by facilitating the collection of data required and urging manufacturers of naloxone to file applications for such status change.

To Manufacturers of Naloxone

- Promote affordable, stable, and transparent pricing policies to ensure access to naloxone and other essential medicines.

- Apply to the FDA for “over-the-counter” status for naloxone products.

I.Background

Overdose Deaths in the US

The human toll of what the CDC has called an “epidemic” of overdoses involving opioids is enormous, affecting individuals and families, and overwhelming communities throughout the US.

Most people who die of opioid-related overdose are aged 25 to 54, white, and more likely to live in rural areas than ever before.[4] The rate of opioid-related overdose deaths in rural counties is 45 percent higher than in metropolitan counties.[5] Most deaths occur in men, but rates of opioid-related overdose among women are increasing rapidly.[6] In February 2017, 52 people overdosed during a 32-hour period in Louisville, Kentucky, many after using heroin to which fentanyl had been added.[7] Thousands of people each month are losing friends and loved ones, children are losing their parents, and with overdose deaths continuing to rise, there appears to be no end in sight.

In 2015, 52,404 people in the US died of a drug overdose, more than any previous year on record.[8] Approximately 33,000—or 63 percent—of these deaths involved the use of opioids.[9] Between 2000 and 2015, drug overdose deaths were equally split between heroin and opioid pain medicines such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, methadone, and morphine, as illustrated in Graph 1 below from the CDC.[10] Drug overdose deaths continue to rise, increasing more 11.5 percent between 2014 and 2015, with opioid-related deaths increasing more than 15 percent during that period.[11]

Graph 1: Drug Overdose Deaths Involving Opioids, by Type of Opioid, US, 2000-2015.[12]

Many opioid-related deaths are not solely attributable to heroin: deaths from overdose related to fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid, have more than doubled during the period 2013-2014 and continued to rise in 2015.[13] In addition, other drugs are frequently involved: 63 percent of fentanyl-related overdose deaths involve another drug, most often heroin or cocaine, and 51 percent of heroin-related overdose deaths involve one or more other drugs, primarily cocaine.[14] One in three overdose deaths from benzodiazepines, such as Xanax, involve opioids, primarily oxycodone.[15]

The factors contributing to what the CDC has called an “epidemic” of overdoses involving opioids are numerous and complex and include intense marketing of pain medications by pharmaceutical companies; weak enforcement of regulations of prescriptions for pain medications by physicians and pain management clinics; and increasing rates of drug use in areas beset by economic distress.[16] Nationwide, drug treatment services are limited and fail to meet demand, particularly in rural areas and for those lacking health insurance.[17] Indeed, the impact of the opioid crisis on rural areas is part of an increasing health disparity between rural and urban areas throughout the United States. A 2017 CDC report indicates that rural Americans are more likely to die from each of the top five causes of death in the nation: heart disease, cancer, chronic lower respiratory disease, stroke, and unintentional injuries. The latter category includes accidental overdoses.[18]

Under the Obama administration, public health and law enforcement officials adopted a multi-tiered response that combined law enforcement strategies with an emphasis on public health. Summarized in the US National Drug Control Strategy of 2016, these efforts attempt to address supply by increasing restrictions on prescriptions for opioid pain medications, implementing systems for tracking individual prescriptions to prevent duplication, and instituting law enforcement initiatives that target trafficking and distribution.[19]

At the same time, the president and federal agencies promoted increased availability of health services and drug dependence treatment, primarily through the ACA, which mandates the inclusion of behavioral health services in insurance plans. These provisions have allowed millions of people to access drug dependence treatment, including medication-assisted therapies such as buprenorphine and methadone. Insurance coverage under the ACA has also enabled millions of people to have preventative care visits that can be key to identifying substance use disorders before they become more severe or result in overdose, and are important for diagnosing and treating mental health issues that often contribute to the development of drug dependence.[20]

The Department of Justice also promoted utilization of naloxone by law enforcement, issuing a “tool kit” to train local police and sheriff’s offices to carry naloxone.[21] In 2016, Congress authorized increased funding to combat opioid use and overdose deaths, making money available to state public health agencies for education, prevention, and treatment.[22]

Much remains to be done to combat rising opioid use and overdose in the US. There are no easy answers, but punitive approaches to drug use and possession have been proven to be ineffective and counterproductive.[23] Poverty and unemployment are significant risk factors for substance use, and addressing these issues should be key elements of the response.[24] Across the US, access to mental health services and behavioral health treatment lags far behind need, most acutely in rural areas.[25] Primary health care also plays an important role in identifying potential substance abuse problems before they develop into diagnosable disorders.[26]

The Obama administration’s approach also attempted to reduce supply, by stepping up enforcement of drug trafficking laws (targeting high volume heroin dealers); working with states to tighten restrictions on prescription of opioids for pain; and tracking those prescriptions to eliminate duplication and diversion.[27] But equally important was public health: the Department of Justice and the Office of Drug Control Policy joined the Department of Health and Human Services in emphasizing health services, including access to treatment and overdose prevention.[28]

Most importantly, it significantly expanded access to drug treatment as the ACA mandates insurers to offer parity in coverage for medical as well as mental health issues. In the 32 states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA, 1.3 million people with a substance use disorder diagnosis who were not previously insured now are receiving treatment for drug dependence.[29]

The American Health Care Act (AHCA), the Republican proposal to “replace” the ACA, removed the essential benefits requirements from the Medicaid program, leaving crucial coverage decisions, including whether mental health care be covered, to individual states.[30] The AHCA was withdrawn on March 4, 2017, without a vote in the House of Representatives.[31] If similar legislation is enacted in the future, it could have devastating impact on what progress has been made to help people caught up in the opioid crisis.

Overdose Death Prevention: Making Naloxone Available

According to WHO, comprehensive overdose prevention programs involve multiple components that range from reducing availability of prescription and illicit opioids to ensuring the availability of evidence-based, medication-assisted treatment for opioid dependence, including methadone and buprenorphine.[32] Safe injection sites, such as those operating in Vancouver, British Columbia, have been shown to reduce death from overdose and have been proposed for several US cities.[33]

Discussion of each of these elements is beyond the scope of this paper, but when overdose does occur, a critical component to prevent death from overdose is access to naloxone. As overdose deaths involving opioids have increased in the US, so has the importance of, and demand for, naloxone.

When someone overdoses on opioids, their breathing stops or becomes severely limited. Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that can reverse an overdose by restoring respiratory capacity if given in the early stages of an overdose event.[34] This life-saving medication is a safe, non-controlled substance that has no potential for abuse or overdose and is not harmful if given to someone who is not experiencing an opioid overdose.[35] For more than four decades, emergency rooms have routinely administered naloxone for overdoses involving opioids.[36]

Naloxone has long been a prescription medication that could not be sold “over-the-counter.” However, with a modicum of training, it can be safely and easily administered by medical and non-medical personnel, either by intramuscular injection via syringe or by intranasal application as a nasal spray. WHO, the US Office of National Drug Control Policy, US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the CDC, and other national and international health experts have endorsed making naloxone available to medical personnel and trained lay persons to prevent death from overdoses involving opioids.[37] Naloxone is included on WHO’s list of essential medicines.[38]

In the last several years, many states and the federal government have taken steps to increase the availability of naloxone to those most likely to be at the scene of an overdose. In most cases, this is drug users themselves. A nationwide study of naloxone reversals showed that 81 percent of the reversals were performed by drug users helping a friend, companion, or acquaintance.[39] Police, especially in rural areas, can also be the first responders to an overdose emergency, and, in 2013, the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy has called for naloxone to be “in the patrol car of every law enforcement officer in the nation.”[40]

Naloxone’s status as a prescription medication requires state legislatures to act in order to expand its availability beyond a traditional medical setting. At the urging of advocates, and with support from numerous organizations, including the US Conference of Mayors, the American Medical Association, and the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, the majority of states have addressed this legal barrier, primarily through permitting third-party prescriptions of naloxone and “standing orders.” Under the traditional prescription model, a doctor prescribes directly to a patient whom he or she has examined. Third-party prescriptions permit the doctor to prescribe not only for their own patients but to family members, caregivers, and others who are likely to be in a position to assist in an overdose event.[41]

“Standing orders” expand that concept to permit distribution of a prescription medication like naloxone to anyone who meets certain criteria, such as people who use opioids, their family members, and others who may use naloxone to assist in the case of an overdose.[42] In the context of naloxone, the standing orders can be issued by state medical officials or by local physicians if the law allows. Distribution can be limited to pharmacists or can, explicitly or by implication, permit dispensing of naloxone by lay persons, including community organizations and drug treatment centers.[43]

Thirty-six states have passed Good Samaritan legislation that provides at least partial legal protection from arrest or criminal prosecution in the event that emergency services are called to respond to a drug overdose (see Appendix I). This is important not only to decrease reluctance to call authorities in an overdose emergency, but also because combining naloxone administration with a 911 call is best medical practice, as there may be need for additional medical services in case of an overdose.[44] The Appendix identifies the states that have authorized third-party prescriptions or standing orders, have Good Samaritan protections for calling 911, and have granted protection from civil or criminal liability for administration of naloxone.[45]

Wider access to naloxone, particularly the advent of “take-home” naloxone, has saved lives across the nation. Harm reduction programs have been distributing naloxone to drug users since 1996, and, as of 2010, access to naloxone among community groups, people who use drugs, their families and friends, as well as firefighters, Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals, and drug treatment centers has increased rapidly. Between 1996 and 2014, at least 30,000 overdoses were reversed with this medication, the majority since 2010.[46] This number underestimates the actual reversal rate, as many go unreported. Most of these reversals were done by drug users themselves, often the first responders to an overdose situation.[47]

Indeed, although carrying naloxone by law enforcement is important, someone at the overdose scene had to call 911 in the first place, underscoring the importance of ensuring that naloxone can be distributed to people who use drugs and their families and friends. Although both third-party prescriptions and standing orders facilitate distribution of naloxone, under third-party prescriptions, a doctor must still write individual prescriptions. Standing orders, such as those in effect in Alaska, that explicitly permit community groups to distribute naloxone are preferable for ensuring access for people who use drugs.[48]

|

North Carolina’s Model for Effective Naloxone Distribution The state of North Carolina has developed an effective response to a rate of overdose involving opioids that in some counties is the highest in the nation.[49] Between 2013 and 2015, the state legislature passed a series of bills and amendments that have resulted in issuance of standing orders expanding distribution of naloxone by pharmacists without a prescription.[50] At the same time, Good Samaritan legislation was passed to grant immunity from prosecution for small amounts of drugs and paraphernalia to those who called 911 in case of overdose emergency. This legislation was later expanded to include people on probation and parole.[51] Since August 2013, the community-based North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition (NCHRC) has distributed more than 38,000 naloxone kits to every part of the state and recorded more than 6,000 overdose reversals.[52] Naloxone is also available at many pharmacies via the state medical director standing order, at almost every methadone clinic in the state, and is carried by at least 139 police departments and sheriffs’ offices.[53] The North Carolina response is characterized by a grassroots community effort to prevent overdose that utilizes more than 170 community-based contractors to distribute naloxone throughout the state. In many cases, this effort is led by people who use drugs and their friends and families. Parents are using naloxone to save the lives of their teenagers, husbands are saving wives, and people who use drugs are forming groups such as the Urban Survivor’s Union in Greensboro in order to ensure that naloxone is increasingly available. Robert Childs, director of NCHRC, told Human Rights Watch: “Our goal is to get a ‘rescue kit’ into the hands of every person in North Carolina who needs one. No one should die an unnecessary death in North Carolina or anywhere else.”[54] But even in North Carolina, barriers remain. As discussed below, law enforcement in numerous counties hard-hit by overdose deaths still do not carry naloxone. |

II. Barriers to Increased Access to Naloxone

In response to what the CDC has called an “epidemic” of deaths from opioid overdose, Congress has passed legislation increasing funding for both law enforcement and public health response, including expansion of drug treatment and overdose prevention.[55]

Under the Obama administration, the federal government publicly prioritized making naloxone available to prevent overdose deaths and progress has been made in quite a few states toward expanding access to this essential medicine. However, significant obstacles persist in practice.

Human Rights Watch has documented the terrible human cost of criminalizing personal drug use and possession in the United States, an approach that, for decades, has devastated individuals, families, and communities.[56] Criminal laws increase health risks for people who use drugs in a variety of ways, including by driving people who use drugs underground and away from health services; undermining access to information about prevention and treatment; and increasing the likelihood that people will inject drugs alone or in unsafe conditions, exacerbating the risk of death from overdose.[57]

Criminalization of drug use also has a direct effect upon efforts to prevent overdose deaths. Witnesses are present at the majority of overdose situations, but fear of prosecution deters many from seeking help or calling 911.[58] Good Samaritan laws prohibit arrest or prosecution for small amounts of drugs or paraphernalia found at an overdose scene and have been proven to increase willingness to call 911 in states where they have been implemented. In Washington state, for example, 88 percent of drug users surveyed said they would be more likely to call 911 in case of an overdose emergency because of the Good Samaritan law passed in 2010.[59]

Fourteen states, however, have no Good Samaritan laws directed to those who witness a drug overdose, and laws vary widely across the country in terms of the scope of protections provided.[60] In 17 states, people at the scene of an overdose who call 911 are protected from prosecution on drug related charges but not from arrest, a distinction that is unlikely to promote calls to emergency services by those wishing to avoid interaction with the criminal justice system (see Appendix I). The state of Utah’s protection is limited to raising the 911 call as an affirmative defense following prosecution on drug possession charges.[61]

Moreover, legislatures in at least 10 states have enacted laws intended to punish drug dealers for overdoses that can be traced to the product that they sold.[62] These “drug delivery” laws permit prosecutors to seek murder or manslaughter charges where drugs sold allegedly resulted in an overdose death.[63] These laws have the potential to undermine the effectiveness of Good Samaritan laws as they have been used to prosecute persons at the scene who accidentally administered a fatal dose to the deceased.[64]

In 2014, the Louisiana legislature, for example, passed a Good Samaritan law that explicitly strips immunity from persons who “illegally provided or administered a controlled dangerous substance” to the individual experiencing the overdose.[65] If fear of arrest or prosecution for drug possession is enough to deter people from calling 911 in an overdose emergency, the prospect of prosecution for murder or manslaughter makes an emergency call even less likely.

Lack of Comprehensive Harm Reduction Programs

Harm reduction programs are a key component of protecting the right to health for people at risk of overdose. Harm reduction is a way to prevent disease and promote health that “meets people where they are,” both philosophically, by refraining from judging their behavior, and literally, by providing services on the street and other locations outside traditional health care facilities.

Harm reduction focuses on promoting scientifically proven ways to mitigate health risks associated with drug use, including access to sterile syringes; evidence-based treatment; and overdose prevention information and tools, including naloxone.[66] Overdose deaths often involve combinations of substances in addition to opioids, including alcohol, and harm reduction programs can provide information about the dangers of these combinations.[67]

Evidence accumulated over decades of study demonstrates that harm reduction programs do not increase drug use or crime in neighborhoods where they are located.[68] Indeed, public safety and the safety of law enforcement officers are enhanced by removing used syringes from the street and encouraging disclosure of syringes to officers during searches.[69] Harm reduction programs have been shown to lower HIV risk and hepatitis transmission and provide a gateway to drug treatment programs for people who use drugs by offering information and assistance.[70] Comprehensive harm reduction programs promote accessibility of health services by reaching out directly to a population likely to lack health insurance and reluctant to interact with health care systems due to stigma and discrimination.[71]

The city of Baltimore, for example, distributes the vast majority of its naloxone through its syringe exchange programs because it sees this as the most effective way to reach the target population. As Mark O’Brien, director of opioid overdose prevention and treatment for the Baltimore City Health Department, told Human Rights Watch:

We have made it a priority to train and equip every single client of our needle exchange program with naloxone. With limited resources, we know it’s the best way to get naloxone into the hands of people at the greatest risk of experiencing or witnessing an overdose. It’s one more way our [needle exchange program] is keeping people safe and healthy.[72]

Yet harm reduction and syringe exchange programs remain limited in the US.[73] Opposition to these programs is often based on concerns that harm reduction is not effective, or on moral concerns that providing clean syringes to people who use drugs will increase, condone, or support drug use, despite evidence to the contrary.[74] At the federal level, Congress prohibited funding to syringe access programs (SAPs) for much of the last decade, expressing concern that such programs would undermine the “war on drugs” by “signaling tacit approval [of] illegal drug use.”[75] In vetoing a bill that would have expanded availability of naloxone by permitting standing orders, Maine Governor Paul LePage wrote in April 2016 that “allowing addicts to have naloxone on hand only perpetuates the cycle of addiction…. Naloxone does not truly save lives, it merely extends them until the next overdose.”[76] The state legislature voted to override his veto, an important step in a state where overdoses increased more than 30 percent between 2014-2015.[77]

Stigmatization and fear of people who use drugs also contributes to reluctance to endorse harm reduction approaches. In West Virginia, where syringe exchange programs have operated only since 2015, officials noted a profound change in public attitudes toward the client since the exchanges began to operate. Dr. Michael Kilkenny of the Cabell-Huntington Department of Health told Human Rights Watch:

We are not like California or New York—we have not been doing syringe exchange for decades, it is new to us here. But since we started, people now see that the clients use the exchange and appreciate it. There is [now] an understanding that people who use drugs are not demon-possessed, they’re human beings.[78]

The federal ban on funding for syringe exchange was modified in 2016 in response to serious outbreaks of HIV and hepatitis in rural counties of Indiana, Ohio, and Kentucky with high rates of opioid use. Federal funds may now be used for staff salaries, office rental, and other expenses incurred by SAPs located in areas that demonstrate high risk of, or are experiencing high rates of, HIV and hepatitis transmission, but these funds can still not be used to purchase syringes themselves.[79] Though syringes are not expensive (3 to 5 cents per syringe), they create an additional cost barrier for states, localities, and community organizations. Since May 2016, 24 jurisdictions (18 states and 6 counties) have applied for and received nearly a million dollars in funding from the CDC to support syringe exchange programs.[80]

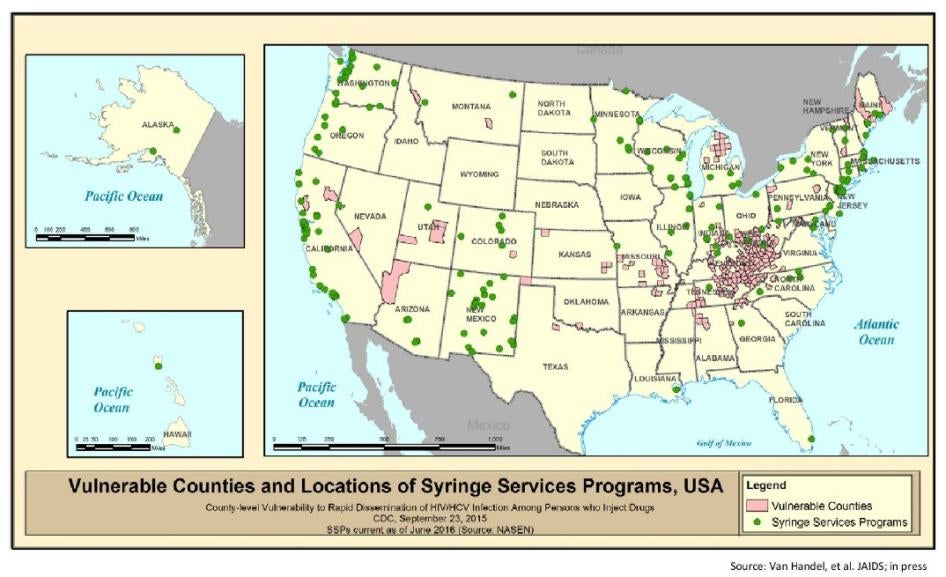

At the state level, however, many SAPs operate in difficult and uncertain circumstances. There are approximately 261 SAPs in the US (see Appendix II), but many work under limited or non-existent legal authority. As of December 2016, only 21 states and the District of Columbia explicitly authorized syringe exchange, and some of the programs are pilots or temporary.

Syringe exchange programs exist in another 18 states and Puerto Rico, but, in many of them, drug paraphernalia laws prohibit distribution and/or possession of syringes for non-medical purposes, and pharmacy practice laws and controlled substance regulations combine to erect serious barriers to these programs (see Appendix II).

In addition, SAPs tend to be located in urban areas while significant gaps remain in rural areas that are experiencing dramatic increases in injection drug use. Following a severe outbreak in 2015 of HIV transmission among injection drug users in Scott County, Indiana, the CDC identified 220 mostly rural counties in the US that are at risk of a similar outbreak due to high levels of poverty and unemployment, sales of prescription pain medications, overdose deaths, and lack of health services.[81] Of these counties, the vast majority had no syringe exchange programs, and, as the map below illustrates, many had no such programs nearby.

Map 1: Vulnerable Counties and Locations of Syringe Services Programs, USA[82]

As the CDC stated in this report:

The outbreak in Scott County, Indiana was notable for the absence or minimal availability of harm reduction strategies to prevent [intravenous drug use-associated] HIV and [hepatitis C] infections, such as addiction treatment and rehabilitation, medication-assisted therapy and syringe service programs. This outbreak illustrated the need for harm reduction strategies suited to the rural context.[83]

Legalizing harm reduction services, including syringe exchange, can have a significant impact on the distribution of naloxone. North Carolina, for example, legalized the operation of SAPs in July 2016. According to Robert Childs, director of the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition:

Syringe exchange programs are an essential vehicle for making sure that people who use drugs have access to naloxone, because these are services targeted to those who need them the most. Before syringe exchange was legal, we worked with ‘underground’ programs on the street, but people were reluctant to come to us for help.[84]

Childs told Human Rights Watch that he expects that legalization of syringe access programs will significantly increase naloxone distribution throughout the state.[85] In Hickory, North Carolina, for example, the local harm reduction program has been able to service more than four times as many clients since syringe exchange became legal in the state.[86]

West Virginia also has responded to one of the worst opioid crises in the nation by endorsing syringe exchange and naloxone distribution, and by taking advantage of federal funding opportunities to support these programs. In 2015, West Virginia’s age-adjusted rate of deaths from drug overdose was 41.5 per 100,000, more than double the national average of 16.3. Between 2013 and 2015, 1,922 people died of drug overdose in the state.[87]

In 2016, the CDC identified 28 counties in West Virginia at high risk of severe HIV outbreak due to high levels of poverty and unemployment, sales of prescription pain medications, overdose deaths, and lack of health services.[88] West Virginia is experiencing so many overdose deaths among low-income residents that, for more than five years in a row, state funds to help the indigent bury loved ones have been depleted in a matter of months.[89]

West Virginia has been proactive in promoting harm reduction as part of the state response, enacting law reform necessary to permit syringe exchange programs, distribution of naloxone, and 911 Good Samaritan laws.[90] Six syringe exchange programs operate in the state, with additional programs planned, and a state public health official told Human Rights Watch they plan to pursue “every available funding resource that could be used to support syringe service programs now and in the future.”[91]

West Virginia is also due to expand naloxone distribution statewide via a program funded by CDC that will roll out in 2017. Designed to target non-medical responders to opioid overdose emergencies, the program will make naloxone available to law enforcement, firefighters, and harm reduction groups. Syringe exchange programs will be key sites for distributing naloxone.[92]

In Huntington, West Virginia, for example, county Health Department public health officials have operated a syringe exchange program for 18 months. During that time, the program has provided clean syringes, safe injection information, and naloxone to more than 2,600 people. An estimated 50 naloxone kits per week are distributed, and officials consider this to be the most effective method of reaching those most at risk of overdose. As Dr. Michael Kilkenny of the Cabell-Huntington Health Department said: “When you distribute directly to people who are actually using drugs, you have the highest chance of preventing an overdose death.”[93]

In contrast, Missouri has not enacted the law reform necessary to effectively protect the health of people who use drugs. The rate of death from drug overdose in 2015 was 17.9 per 100,000, higher than the national average of 16.3. Between 2013 and 2015, 3,158 people died in Missouri of a drug overdose.[94] The rate of heroin-related overdoses in St. Louis County in 2013 was more than three times the national average and rose even higher in 2014.[95] In 2016, the CDC identified 12 counties in Missouri at high risk for severe HIV outbreak due to high levels of poverty and unemployment, sales of prescription pain medications, overdose deaths, and lack of health services.[96] The Missouri Network for Opiate Reform and Recovery (MNORR) provides harm reduction services, including syringe exchange and naloxone, in the St. Louis area as well as to neighboring locations in western Illinois. As syringe exchange remains illegal in Missouri, they have operated “underground” for more than three years, without the protection of state law, according to MNORR’s co-founder, Chad Sabora.[97]

In 2014, the Missouri legislature passed a bill providing civil and criminal protection to law enforcement for administration of naloxone, though Sabora told Human Rights Watch that only a “handful” of police departments carry naloxone in the state.[98] In June 2016, the legislature authorized third parties, including community organizations and service providers, to distribute naloxone under standing orders.[99]

However, until SAPs are legalized, distribution of naloxone will be limited. MNORR and other harm reduction advocates continue to press for legalization of syringe exchange, which Sabora says “would make a huge difference in our ability to save lives with not only clean syringes, but also with naloxone.”[100]

Of most concern are states where rates of drug overdose are significant but naloxone access laws are weak and harm reduction is limited. In Wyoming, for example, the rate of death from drug overdose, at 16.4 per 100,000 people, is near the national average of 16.3, and 303 people died of overdose between 2013 and 2015.[101] According to state health officials, only ambulances in Wyoming carry naloxone.[102] Until lawmakers clear the legal barriers to expanded access, people will continue to die from opioid overdose unnecessarily in the state of Wyoming.

In the 2017 legislative session in Wyoming, two naloxone-related bills passed, one permitting pharmacists to distribute without a prescription, and one establishing standing orders for naloxone to be prescribed for persons at risk of overdose and those in positions to assist in an overdose emergency.[103] A 911 Good Samaritan bill, however, failed to pass; Representative Charles Pelkey, a Democratic sponsor of the bill, explained that although the bill was supported by state law enforcement agencies, immunity from enforcement of the drug laws was not acceptable to opponents of the law.[104] According to Pelkey, it is this emphasis on a criminal law, rather than public health, that prevents Wyoming from legalizing syringe exchange. “If we proposed syringe exchange, we would hear that we were promoting drug use,” said Pelkey, “It’s just not going to happen here.”[105]

Kansas’ death rate from drug overdose is lower than the national average, but increased between 2014 and 2105, and the rate of death from overdose for young people aged 12 to 25 has more than quadrupled in the last decade.[106] 992 people in Kansas died of overdose in Kansas between 2013 and 2015.[107] In 2016, the CDC identified four Kansas counties at high risk of HIV outbreak due to high levels of poverty and unemployment, sales of prescription pain medications, overdose deaths, and lack of health services.[108] Kansas has no laws that promote naloxone access, no Good Samaritan laws, syringe exchange programs are not legal, and syringes are criminalized under drug paraphernalia laws (see Appendices I and II). Kansas public health officials told Human Rights Watch that the state has no plans at this time to further support naloxone access, and that “in light of our current administration,” there are no plans to establish a syringe exchange program in the state.[109]

Arizona’s rate of death from drug overdose in 2015 was three percentage points higher than the national average.[110] In Arizona, 3,707 people died of drug overdose between 2013 and 2015.[111] In 2016, the CDC identified Mohave County as being at high risk of HIV outbreak due to high levels of poverty and unemployment, sales of prescription pain medications, overdose deaths, and lack of health services.[112] Arizona’s naloxone access laws were expanded in 2016 to permit lay persons to distribute without liability, but the state has no Good Samaritan law, syringes are criminalized under drug paraphernalia laws, and syringe exchange programs are not legal. Haley Coles, executive director of Sonoran Prevention Works in Phoenix, Arizona, told Human Rights Watch:

Without a Good Samaritan law, the state is arresting people for asking for help. And syringe exchange programs help to establish trust with people who use drugs…. Without syringe exchange programs, we don’t have a good way of accessing the people who need naloxone.[113]

Michelle Hamby of Peoria, Arizona told Human Rights Watch that her daughter, Breana, became dependent on prescription painkillers when she was 19 and then moved to heroin. Breanna wanted to avoid sharing needles, but it was a constant struggle to find clean syringes; pharmacies would not sell them to her, and she sometimes resorted to stealing her mother’s diabetic syringes. According to Michelle, she contracted hepatitis C for which she sought treatment.[114] While in rehabilitation she committed to staying away from opioids.

But opioid dependence is a chronic, relapsing disease.

Michelle came home one day and found Breana lying in the bathroom. She had overdosed on heroin. Michelle believes that harm reduction services could have saved her daughter’s life. “If syringe exchange was legal, she might not have gotten hepatitis.”[115]

In North Dakota, people are likely also dying needlessly from overdoses. The state’s rate of overdose deaths is about half the national average (8.6 per 100,000 people versus 16.3) but is trending upwards. Between 2013 and 2014, the state had a 125 percent increase in overdose deaths—the nation’s highest increase—and its rate increased further in 2015.[116] Since 2013, 124 people have died of overdose in North Dakota.[117] In March 2016, three people died from heroin overdose in one week in the city of Fargo.[118]

The state has passed legislation expanding access to naloxone, permitting pharmacists to dispense it to both “patients” who may be at risk of overdose and “those who may be in a position to assist” someone at risk.[119] A Good Samaritan law is also in place.[120] However, distribution of naloxone is limited to medical providers and pharmacies, which is not likely to be adequate for a population that is underserved by the health care system.

Communities with active training and distribution programs for naloxone show greater reductions in overdose death rates than those without such programs.[121] According to Mark Hardy, director of the State Board of Pharmacy, the board is not aware of any non-pharmacy provider in the state, and the effectiveness of the pharmacy-only approach is unknown as the state does not collect data on the extent of distribution of naloxone by pharmacies in North Dakota.[122]

The North Dakota legislature, however, has passed a bill legalizing syringe exchange on the grounds of a public health emergency in relation to HIV and hepatitis C transmission. New HIV cases have more than tripled in the state since 2010 and show no signs of slowing down, and a recent Department of Health report indicates increases in both injection drug use and transmission of hepatitis C.[123] The passage of the bill is a positive public health response that carries potential for expanding naloxone distribution, but current laws must be amended to permit distribution of naloxone at syringe exchange sites.

Montana also has been slow to respond, but may now be moving to address its overdose problem. The rate of drug overdose is below the national average (13.8 per 100,000 people vs. 16.3) but is on the rise, increasing from 12.4 in 2014.[124] Since 2013, 400 people have died from drug overdoses in Montana, but the state legislature has taken no action with regard to naloxone. There are no standing orders permitting pharmacists or community groups to distribute naloxone, no Good Samaritan laws address calling 911 for a drug overdose, and no immunity from civil or criminal liability is given for naloxone administration. Syringe exchange is not legal in the state.

As of March 2017, however, a bill was pending in the Montana state assembly that would authorize standing orders for the distribution of naloxone to individuals at risk of overdose and those in a position to assist in an overdose emergency, including harm reduction organizations. The bill further provides civil and criminal immunity for administering naloxone as well as Good Samaritan protection from arrest and prosecution on specified drug-related charges.[125] Representative Jim Hamilton, one of the bill’s Democratic sponsors, says the bill is necessary because even first responders are not carrying naloxone due to liability concerns. “Montana is not immune to the opioid problem. We can see the wave rolling in this direction.”[126]

Mindy Fuzesy is co-founder of the Kalispell Valley Drug Task Force, a community organization working to reduce opioid use and death from overdose in Kalispell, Montana. According to Fuzesy, Montana has been slow to respond to what she calls a “huge problem with heroin in our communities,” and naloxone is simply not available.[127] She said most of the local ambulance services will not carry it as they are volunteers and are concerned about civil or criminal liability for administering prescription medications.

Fusezy works as a nurse in the local hospital and said that “children come in overdosed on their parents’ pain medications.”[128] She is not certain why Montana’s response has been slow, but worries the inaction is related to the stigma of drug use: “People just might be thinking, ‘Oh they are junkies, let them die,’ when in reality they are our neighbors, our friends, our family members who deserve a chance at life.”[129]

Training and Education for Law Enforcement

Police play a critical role in the overdose prevention response as they are frequently the first to respond to an emergency call. Thus, state governments need to ensure they are equipped with naloxone and have received adequate training and education. The Office of National Drug Control Policy has called for police to carry naloxone since 2010, and the Bureau of Justice Assistance has released a “Law Enforcement Naloxone Toolkit” to help police departments incorporate naloxone into their response protocols.[130]

But in most states, only a small percentage of law enforcement officers carry naloxone or have received training in its use. According to the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition’s database, 1,214 local police departments in 38 states are carrying naloxone, a fraction of the nation’s approximately 12,000 police departments.[131] Even in North Carolina, where the state and advocates have made significant efforts to engage police departments in response to overdose deaths and where 105 law enforcement agencies in 58 counties carry naloxone, only one-fifth of the state’s police departments are carrying naloxone.[132]

In North Carolina, the two counties with the highest rates in the state, Burke and Wilkes counties, still do not equip their law enforcement officers with naloxone. Indeed, in four of the eight counties with the highest overdose rates in the state, law enforcement officers do not carry naloxone. Between 1999 and 2015, 642 people died of overdoses involving opioids in Wilkes, Burke, Mitchell, and Richmond Counties.[133]

The cost of naloxone is one factor, but some police departments are also reluctant to carry naloxone for reasons ranging from liability concerns to convenience to proper division of labor with emergency medical services.[134] There are no national guidelines for police administration of medical assistance, and practice varies widely across the country. Police departments have been criticized for failing to render medical assistance to victims of police shootings, but many departments defer to EMS for medical emergencies, citing lack of training, proper division of responsibility, liability, and officer safety.[135] One department in Pennsylvania objected to naloxone kits as too difficult to transfer between officers during shift changes.[136]

Adequate training can effectively overcome much of this reluctance. According to Chief Brad Shirley of the Boiling Spring Lakes, North Carolina police department, training and education is vital to increasing participation by police in naloxone availability.

We are often the first to respond to a 911 call, as the ambulance can be miles away. Once we trained our officers on how naloxone was administered and how it could save lives, we have had strong acceptance in our ranks.[137]

Since 2014, Boiling Spring Lakes police have reversed three overdoses in a town of 5,600 people.[138]

In 2016, Congress passed two funding bills that could help to increase participation by law enforcement in overdose prevention efforts. The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act specifically authorizes funds for training, education, and supply of law enforcement agencies in naloxone administration, and the 21st Century Cures Act makes funds available to states to combat the opioid epidemic.[139] To the extent that states take advantage of these and other funding opportunities, utilization of naloxone by law enforcement could become more widespread.

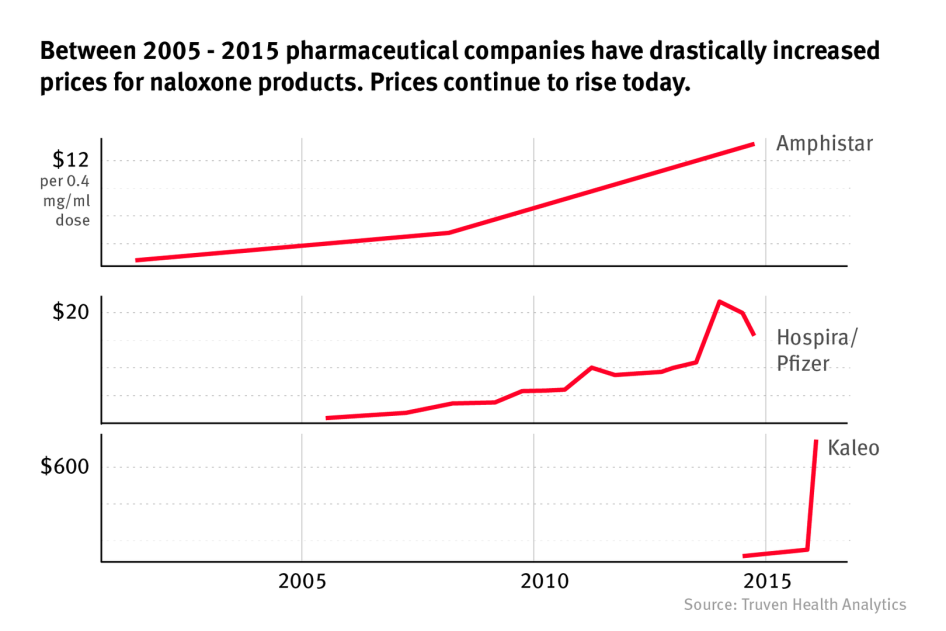

Affordability of Naloxone

A generic medicine, naloxone has been on the market for more than 30 years and should not be expensive. Until 2005, the price of 0.4 mg/ml in the injectable format (for use with a syringe) was less than a dollar.[140] In 2008, when opioid use and overdose began to spike nationwide, Hospira (now Pfizer) was the only manufacturer of the injectable syringe format and began increasing its prices. As of late 2016, four other manufacturers were participating in the naloxone market, producing different dosages and formats for application. In the last decade, and particularly in the last two years, pharmaceutical companies have increased prices for naloxone products dramatically (see Graph 2 below).[141]

Graph 2: Trends in Naloxone Prices[142]

Identifying current prices of naloxone products is challenging as prices change according to recipients, contracts, discounts, rebates, and markups that are frequently not transparent. Table 1 presents the documentation of naloxone pricing in a December 2016 article in the New England Journal of Medicine.[143] As indicated in Table 1 below, the price ranges from $20 to $4,500, depending upon dosage, format, and manufacturer. The most expensive version is sold by Kaleo, Inc., which produces an auto-injector that looks like a small cartridge and delivers vocalized instructions for use. According to pharmacists, the insurance co-pay alone for this product ranges from $70-$200, depending on company discounts and rebates.[144] The Narcan® product from Adapt Pharmaceuticals consists of a 4 mg/.1ml nasal spray application at approximately $150 per package of two, with a special price of $75 available for community programs, first responders, and other groups designated by the manufacturer as eligible for this “public interest price.”[145]

Table 1: Recent and Current Prices for Naloxone[146]

|

Naloxone Product |

Manufacturer |

Previous Available Price (yr) |

Current Price (2016) |

|

Injectable or intranasal 1 mg/1 ml vial (2ml) (mucosal atomizer device separate |

Amphastar) |

$20.34 (2009) |

$39.60 |

|

Injectable 0.4 mg/1 ml vial (10 ml) |

Hospira |

$62.29 (2012) |

$142.49 |

|

Injectable 0.4 mg/1 ml vial (1 ml) |

Mylan |

$23.72 (2014) |

$23.72 |

|

Injectable 0.4 mg/1 ml vial (1 ml) |

West-Ward |

$20.40 (2015) |

$20.40 |

|

Auto-injector, two pack of single-use prefilled auto-injectors (Evzio®)[147] |

Kaleo (approved 2014) |

$690.00 (2014) |

$4,500.00 |

|

Nasal spray, two pack of single-use intranasal devices (Narcan®) |

Adapt (approved 2015) |

$150.00 (2015) |

$150.00 |

Companies reportedly assert that their pricing of the medication is justified by manufacturing costs, investment in research and development for more accessible, easy- to-use formats, and by their extensive donation, rebate, and discount programs for government entities, community organizations, and individual consumers covered by insurance.[148] However, industry critics maintain that there is little transparency regarding the impact of these factors on the cost to the manufacturer, leaving government and consumers without tools to evaluate these claims.[149]

Impact of Pricing on Access

Many departments of health and some community organizations do receive industry rebates and discounts, but prices remain out of reach for many smaller organizations and individuals and are subject to the uncertainty of manufacturer’s goodwill. Price has proven to be a barrier to wider distribution of naloxone for government entities as well as community organizations.

A survey of 136 organizations distributing naloxone at 644 locations throughout the US reported that due to price, one-third experienced supply difficulties and one-half had inadequate resources to sustain or expand distribution at current levels.[150] In an article titled “The Rising Price of Naloxone: Risk to Efforts to Stem Overdose Deaths” from a December 2016 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, doctors expressed concern that price increases in naloxone were contributing to “relatively slow” naloxone expansion given the extent of the overdose health crisis.[151]

In November 2016, Hospira/Pfizer announced that it would provide its naloxone product (0.4 mg/ml vial, used with a syringe) to specified community organizations for a significantly reduced price.[152] While this was welcome news for harm reduction advocates, these agreements are subject to non-disclosure clauses, are limited in time, and pricing for naloxone continues to be subject to the goodwill of the manufacturer. In addition, many public entities prefer not to utilize naloxone with syringes, citing ease of use concerns, and the prices of alternative formats are significantly higher.

In Baltimore, for example, the Health Department and its partners distributed over 20,000 naloxone kits between January 2015 and February 2017, primarily through its syringe exchange program, community organizations, and law enforcement.[153] According to Mark O’Brien, director of overdose prevention for the city, the price of the nasal, non-syringe formats purchased by the city has nearly doubled since 2014, significantly reducing the number of kits that the city is able to provide to those in need.[154] At the same time, budgets for naloxone have decreased, and the practice of adding fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that makes heroin more potent, continues to rise, requiring more naloxone to reverse each overdose. The combination of these factors, says O’Brien, has “cut in half” the ability to meet the need for naloxone in Baltimore.[155]

One answer may lie in the state’s Medicaid program, which approved the naloxone product Narcan® for reimbursement coverage in July 2016. Under this program, Narcan® may be purchased at pharmacies for a $1 co-pay for Medicaid patients. According to O’Brien, many people who use drugs are reluctant to purchase naloxone at pharmacies, fearing judgment or refusal. As a consequence, the city is considering ways to expand availability through direct distribution of naloxone to Medicaid-eligible recipients.[156]

Community organizations face even greater obstacles to access as a result of naloxone prices.

In Orange County, California, Aimee Dunkle’s son, Ben, died of a heroin overdose in 2013. He was with three other people at the time, whom Dunkle believes could have saved him if they had been carrying naloxone. Fearing arrest, they did not call 911 and dropped Ben’s body in a parking lot.[157] In May 2015, Dunkle started the Solace Foundation, a small non-profit organization dedicated to preventing overdose in her community. The cheapest form of naloxone the Solace Foundation can buy, however, costs more than her organization can afford while operating on what she calls a “shoestring budget.”[158] Dunkle relies on donations that she receives from pharmaceutical companies like Kaleo, Inc. and Adapt, as well as from larger harm reduction organizations, but those donations are intermittent.

Deaths from heroin overdose in Orange County increased by 114 percent between 2012 and 2015, according to the Orange County Sheriff’s Department.[159] More than 500 overdose reversals have been reported to the Solace Foundation from people who received naloxone kits from the foundation between February 2016 and February 2017.[160] Yet the Orange County Health Care Agency does not support the Solace Foundation’s efforts, either by supplying naloxone or funding purchase of naloxone, nor does it provide funding or support for the local syringe exchange run by volunteers.[161]

In 2004, WHO, recognizing that 30 percent of the world’s population lacks access to essential medicines, issued a set of guidelines for countries to promote equitable access.[162] The guidelines recommend policies to help ensure adequate supply, affordable pricing, and sustainable financing of medications. In the area of pricing, the guidelines provide numerous options that governments may use to keep prices of essential medicines affordable, which include bulk purchasing, price negotiation, supporting generic alternatives, and reducing mark-ups in the supply chain.

In the US, Medicaid and Medicare authorize coverage for naloxone in and outside medical settings; the government has negotiated discount prices for naloxone purchase on behalf of the Veterans Administration and, in legislation passed in 2012, has streamlined the approval process for generic medications.[163] But as prices remain problematic for public agencies, community groups, and individuals, government officials have expressed concern about the cost of naloxone and about high prices for prescription medications more generally, including recent price hikes for HIV and hepatitis C medications as well as the EpiPen, used for allergic reactions.[164] Since August 2016, members of Congress have sent a series of letters to the five leading naloxone manufacturers objecting to the upward trend in price amid a serious opioid epidemic.[165] Numerous bills pending in the 115th Congress propose loosening restrictions on the import of medications from Canada and other countries in response to price concerns.[166]

The Fair Pricing Coalition (FPC), a national coalition of activists and policy leaders that focuses on ensuring access to medications for HIV and viral hepatitis, released a paper in December 2016 identifying steps that can be taken in the first 100 days of a new presidential administration to help control drug costs for patients that are privately insured, underinsured, and uninsured.[167]

The FPC maintains that the regulatory framework designed to control drug costs that was established in the 1990s needs to be strengthened and modernized in four areas: fixing the formulas that currently define price ceilings for government reimbursement of medications under Medicaid, Medicare, and Veterans’ Affairs programs; strengthening penalties for extreme and unjustified price hikes; increasing coordination of state and federal purchasing power; and increasing transparency on the part of manufacturers as to the true price of medications. Like WHO guidelines, the FPC paper provides numerous options for the federal government to ensure that essential medicines are affordable. According to Sean Dickson of the FPC, action in any of these areas has the potential to promote the affordability of naloxone.[168]

Experts from the Network for Public Health Law have suggested specific actions the federal government could take to ensure affordability of naloxone, including ensuring coverage under Medicare and Medicaid, requiring coverage under private insurance (a requirement that the ACA imposes for, among others, most contraceptive prescriptions), and removing barriers to transitioning naloxone to over-the-counter status, a move that they consider to be of primary importance.[169]

As a presidential candidate, Donald Trump called for reducing the price of prescription drugs and met in January 2017 with pharmaceutical companies to address the issue. However, media reports of the meeting indicate that Trump dropped his call for increased government negotiating power for medication purchases as a form of “price-fixing,” instead urging tax cuts and deregulation as his administration’s goals for the industry.[170] Coupled with the Republican party platform’s stance against government-imposed limits on medication prices, the outlook for more robust federal action on naloxone prices remains uncertain at best.[171]

Lack of “Over-the-Counter” Status

One area that the federal government could act to increase access to naloxone is to promote “over-the-counter” (OTC) status. While most states now allow standing orders for naloxone—reducing the barrier posed by past requirements of an individualized prescription—the FDA has not conferred OTC status to naloxone. OTC status would permit purchase not only at pharmacies, but also at convenience stores, vending machines, and other outlets now available for many other safe and effective medications.

In an environment in which drug use is stigmatized, direct purchase without pharmacist contact would remove a significant barrier to access. It would also greatly reduce the administrative burden on community organizations, which would no longer have to locate physicians willing to issue third-party prescriptions or standing orders and comply with other regulations related to prescription medications. According to Eliza Wheeler, project manager for overdose prevention and education at the Harm Reduction Coalition:

Over-the-counter status would make purchase of naloxone much easier and would change the landscape for community-based organizations, as long as the price was affordable.[172]

The FDA is authorized to confer OTC status upon application from the manufacturer, and no manufacturer has filed an application for naloxone. The application process typically requires clinical studies specific to transitioning the product from prescription to OTC, including consumer understanding of labeling instructions, ability to self-diagnose a condition, and other issues.[173]

In July 2015, the FDA held a public meeting to address issues related to access to naloxone, including the transfer of naloxone from prescription to OTC status. The FDA concluded that although there were benefits to OTC status for naloxone consumers, it was necessary for a manufacturer to apply for the transfer, as the cost to conduct the studies necessary to establish the switch to OTC would be prohibitive for any party other than the manufacturer. The law also permits the FDA to entertain a “citizen’s petition” for changing a medication from prescription to OTC status, but the same data would be required.[174] In a blog post dated February 5, 2016, the FDA stated that it was working to improve access to naloxone, including consideration of over-the-counter status.[175]

Last year, the Canadian government faced a similar dilemma: regulations permitted the national health authorities to review applications for naloxone to obtain OTC status but contained no provision for initiating such a change. However, the government and national health authority, Health Canada, examined the evidence and determined that naloxone could now be sold over-the-counter. According to Jane Buxton, harm reduction lead for the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, identifying the need for easier access to naloxone and a more “proactive” approach to regulatory obstacles led the government to approve OTC status for naloxone in Canada.[176]

III. Human Rights Obligations

Instruments

Numerous international instruments address the meaning and scope of the right to health, and international bodies have specifically recognized the right of people who use drugs to comprehensive treatment and care, including overdose prevention, as a human right.

Under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, all persons have the right to the means to protect their health and wellbeing, and governments must protect these rights without discrimination.[177] Evidence-based approaches to drug dependence, including overdose prevention, are key components of both the right to health and the right to life.

The US has signed, but not yet ratified, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the key treaty that protects the right to health. While it is not bound by the covenant, the US government is obligated to refrain from actions that undermine its purpose and effect.[178] The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the body charged with monitoring compliance with ICESCR, has identified, among others, the following core elements of governments’ obligation to protect the right to health:

- To ensure the right of access to health facilities, goods, and services on a non-discriminatory basis, especially for vulnerable or marginalized groups;

- To provide essential [medicines], as from time to time defined under the WHO Action Programme on Essential Drugs;

- To ensure equitable distribution of all health facilities, goods, and services.[179]