Summary

Neal Scott may die in prison. A 49-year-old Black man from New Orleans, Neal had cycled in and out of prison for drug possession over a number of years. He said he was never offered treatment for his drug dependence; instead, the criminal justice system gave him time behind bars and felony convictions—most recently, five years for possessing a small amount of cocaine and a crack pipe. When Neal was arrested in May 2015, he was homeless and could not walk without pain, struggling with a rare autoimmune disease that required routine hospitalizations. Because he could not afford his $7,500 bond, Neal remained in jail for months, where he did not receive proper medication and his health declined drastically—one day he even passed out in the courtroom. Neal eventually pled guilty because he would face a minimum of 20 years in prison if he took his drug possession case to trial and lost. He told us that he cried the day he pled, because he knew he might not survive his sentence.[1]

***

Just short of her 30th birthday, Nicole Bishop spent three months in jail in Houston for heroin residue in an empty baggie and cocaine residue inside a plastic straw. Although the prosecutor could have charged misdemeanor paraphernalia, he sought felony drug possession charges instead. They would be her first felonies.

Nicole was separated from her three young children, including her breastfeeding newborn. When the baby visited Nicole in jail, she could not hear her mother’s voice or feel her touch because there was thick glass between them. Nicole finally accepted a deal from the prosecutor: she would do seven months in prison in exchange for a guilty plea for the 0.01 grams of heroin found in the baggie, and he would dismiss the straw charge. She would return to her children later that year, but as a “felon” and “drug offender.” As a result, Nicole said she would lose her student financial aid and have to give up pursuit of a degree in business administration. She would have trouble finding a job and would not be able to have her name on the lease for the home she shared with her husband. She would no longer qualify for the food stamps she had relied on to help feed her children. As she told us, she would end up punished for the rest of her life.

***

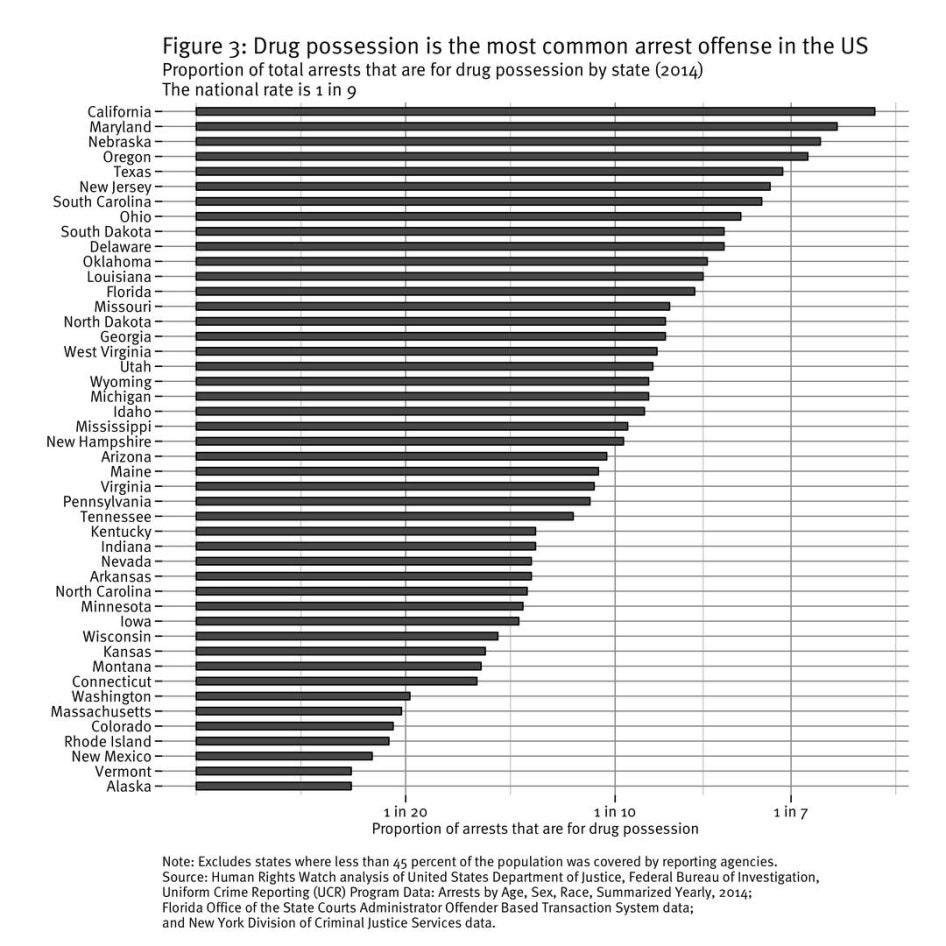

Every 25 seconds in the United States, someone is arrested for the simple act of possessing drugs for their personal use, just as Neal and Nicole were. Around the country, police make more arrests for drug possession than for any other crime. More than one of every nine arrests by state law enforcement is for drug possession, amounting to more than 1.25 million arrests each year. And despite officials’ claims that drug laws are meant to curb drug sales, four times as many people are arrested for possessing drugs as are arrested for selling them.

As a result of these arrests, on any given day at least 137,000 men and women are behind bars in the United States for drug possession, some 48,000 of them in state prisons and 89,000 in jails, most of the latter in pretrial detention. Each day, tens of thousands more are convicted, cycle through jails and prisons, and spend extended periods on probation and parole, often burdened with crippling debt from court-imposed fines and fees. Their criminal records lock them out of jobs, housing, education, welfare assistance, voting, and much more, and subject them to discrimination and stigma. The cost to them and to their families and communities, as well as to the taxpayer, is devastating. Those impacted are disproportionately communities of color and the poor.

This report lays bare the human costs of criminalizing personal drug use and possession in the US, focusing on four states: Texas, Louisiana, Florida, and New York. Drawing from over 365 interviews with people arrested and prosecuted for their drug use, attorneys, officials, activists, and family members, and extensive new analysis of national and state data, the report shows how criminalizing drug possession has caused dramatic and unnecessary harms in these states and around the country, both for individuals and for communities that are subject to discriminatory enforcement.

There are injustices and corresponding harms at every stage of the criminal process, harms that are all the more apparent when, as often happens, police, prosecutors, or judges respond to drug use as aggressively as the law allows. This report covers each stage of that process, beginning with searches, seizures, and the ways that drug possession arrests shape interactions with and perceptions of the police—including for the family members and friends of individuals who are arrested. We examine the aggressive tactics of many prosecutors, including charging people with felonies for tiny, sometimes even “trace” amounts of drugs, and detail how pretrial detention and long sentences combine to coerce the overwhelming majority of drug possession defendants to plead guilty, including, in some cases, individuals who later prove to be innocent.

The report also shows how probation and criminal justice debt often hang over people’s heads long after their conviction, sometimes making it impossible for them to move on or make ends meet. Finally, through many stories, we recount how harmful the long-term consequences of incarceration and a criminal record that follow a conviction for drug possession can be—separating parents from young children and excluding individuals and sometimes families from welfare assistance, public housing, voting, employment opportunities, and much more.

Families, friends, and neighbors understandably want government to take actions to prevent the potential harms of drug use and drug dependence. Yet the current model of criminalization does little to help people whose drug use has become problematic. Treatment for those who need and want it is often unavailable, and criminalization tends to drive people who use drugs underground, making it less likely that they will access care and more likely that they will engage in unsafe practices that make them vulnerable to disease and overdose.

While governments have a legitimate interest in preventing problematic drug use, the criminal law is not the solution. Criminalizing drug use simply has not worked as a matter of practice. Rates of drug use fluctuate, but they have not declined significantly since the “war on drugs” was declared more than four decades ago. The criminalization of drug use and possession is also inherently problematic because it represents a restriction on individual rights that is neither necessary nor proportionate to the goals it seeks to accomplish. It punishes an activity that does not directly harm others.

Instead, governments should expand public education programs that accurately describe the risks and potential harms of drug use, including the potential to cause drug dependence, and should increase access to voluntary, affordable, and evidence-based treatment for drug dependence and other medical and social services outside the court and prison system.

After decades of “tough on crime” policies, there is growing recognition in the US that governments need to undertake meaningful criminal justice reform and that the “war on drugs” has failed. This report shows that although taking on parts of the problem—such as police abuse, long sentences, and marijuana reclassification—is critical, it is not enough: Criminalization is simply the wrong response to drug use and needs to be rethought altogether.

Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union call on all states and the federal government to decriminalize the use and possession for personal use of all drugs and to focus instead on prevention and harm reduction. Until decriminalization has been achieved, we urge officials to take strong measures to minimize and mitigate the harmful consequences of existing laws and policies. The costs of the status quo, as this report shows, are too great to bear.

A National Problem

All US states and the federal government criminalize possession of illicit drugs for personal use. While some states have decriminalized possession of small amounts of marijuana, other states still make marijuana possession a misdemeanor or even a felony. In 42 states, possession of small amounts of most illicit drugs other than marijuana is either always or sometimes a felony offense. Only eight states and the District of Columbia make possession of small amounts a misdemeanor.

Not only do all states criminalize drug possession; they also all enforce those laws with high numbers of arrests and in racially discriminatory ways, as evidenced by new analysis of national and state-level data obtained by Human Rights Watch.

Aggressive Policing

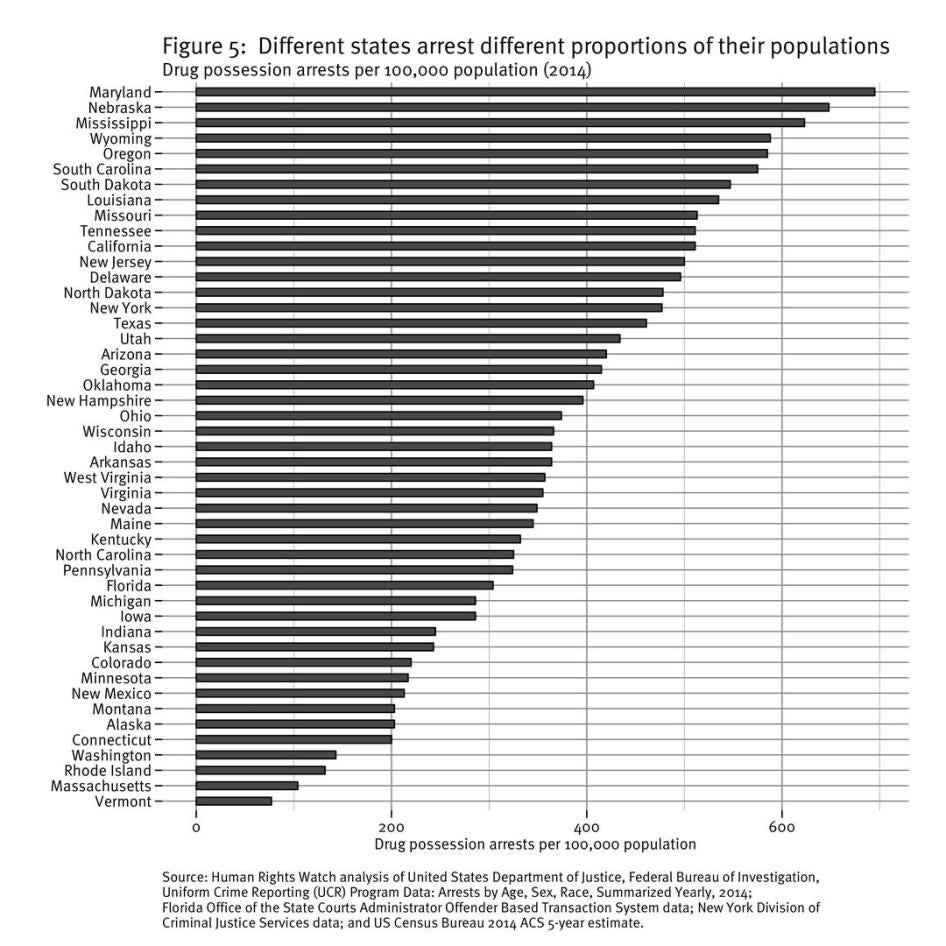

More than one of nine arrests by state law enforcement are for drug possession, amounting to more than 1.25 million arrests per year. While the bulk of drug possession arrests are in large states such as California, which made close to 200,000 arrests for drug possession in 2014, Maryland, Nebraska, and Mississippi have the highest per capita drug possession arrest rates. Nationwide, rates of arrest for drug possession range from 700 per 100,000 people in Maryland to 77 per 100,000 in Vermont.

Despite shifting public opinion, in 2015, nearly half of all drug possession arrests (over 574,000) were for marijuana possession. By comparison, there were 505,681 arrests for violent crimes (which the FBI defines as murder, non-negligent manslaughter, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault). This means that police made more arrests for simple marijuana possession than for all violent crimes combined.

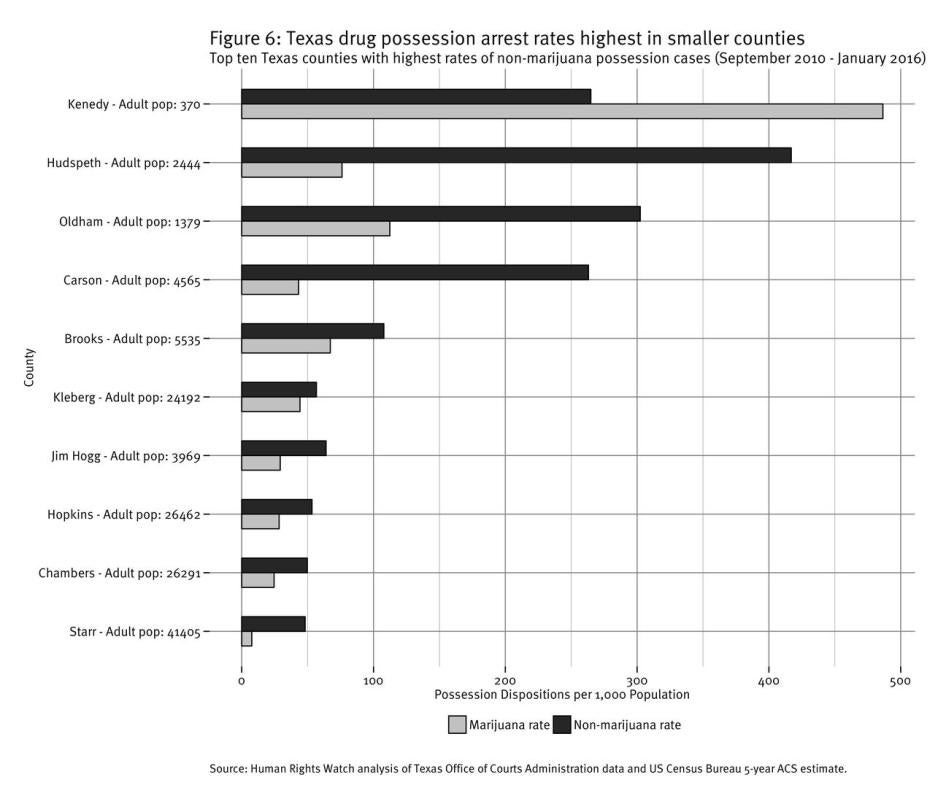

Data presented for the first time in this report shows stark differences in arrest rates for drug possession even within the same state. For example, data provided to us by Texas shows that 53 percent of drug possession arrests in Harris County (in and around Houston) were for marijuana, compared with 39 percent in nearby Dallas County, despite similar drug use rates in the two counties. In New York State, the counties with the highest drug possession arrest rates by a large margin were all in and around urban areas of New York City and Buffalo. In Florida, the highest rates of arrest were spread around the state in rural Bradford County, urban Miami-Dade County, Monroe County (the Keys), rural Okeechobee County, and urban Pinellas County. In Texas, counties with the highest drug possession arrest rates were all small rural counties. Kenedy County, for example, has an adult population of 407 people, yet police there made 329 arrests for drug possession between 2010 and 2015. In each of these states, there is little regional variation in drug use rates.

The sheer magnitude of drug possession arrests means that they are a defining feature of the way certain communities experience police in the United States. For many people, drug laws shape their interactions with and views of the police and contribute to a breakdown of trust and a lack of security. This was particularly true for Black and Latino people we interviewed.

Racial Discrimination

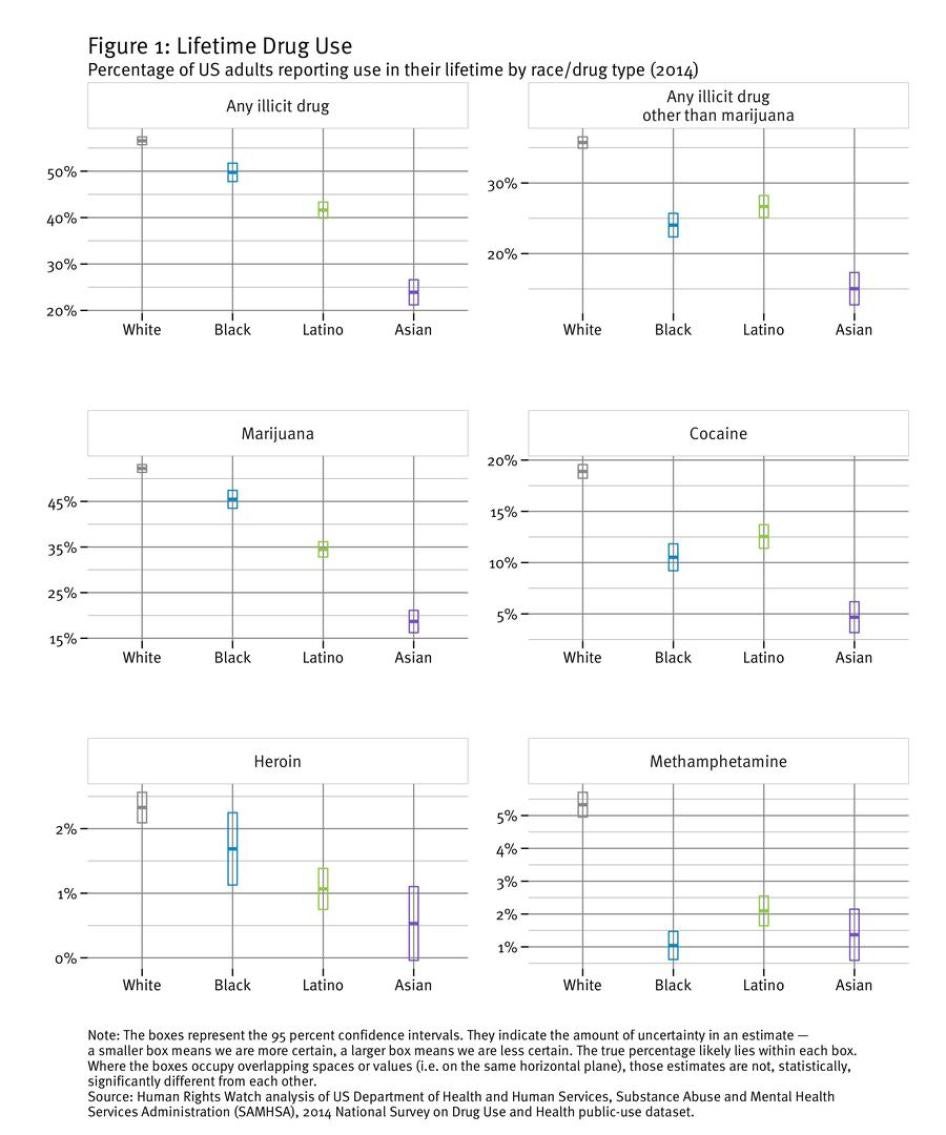

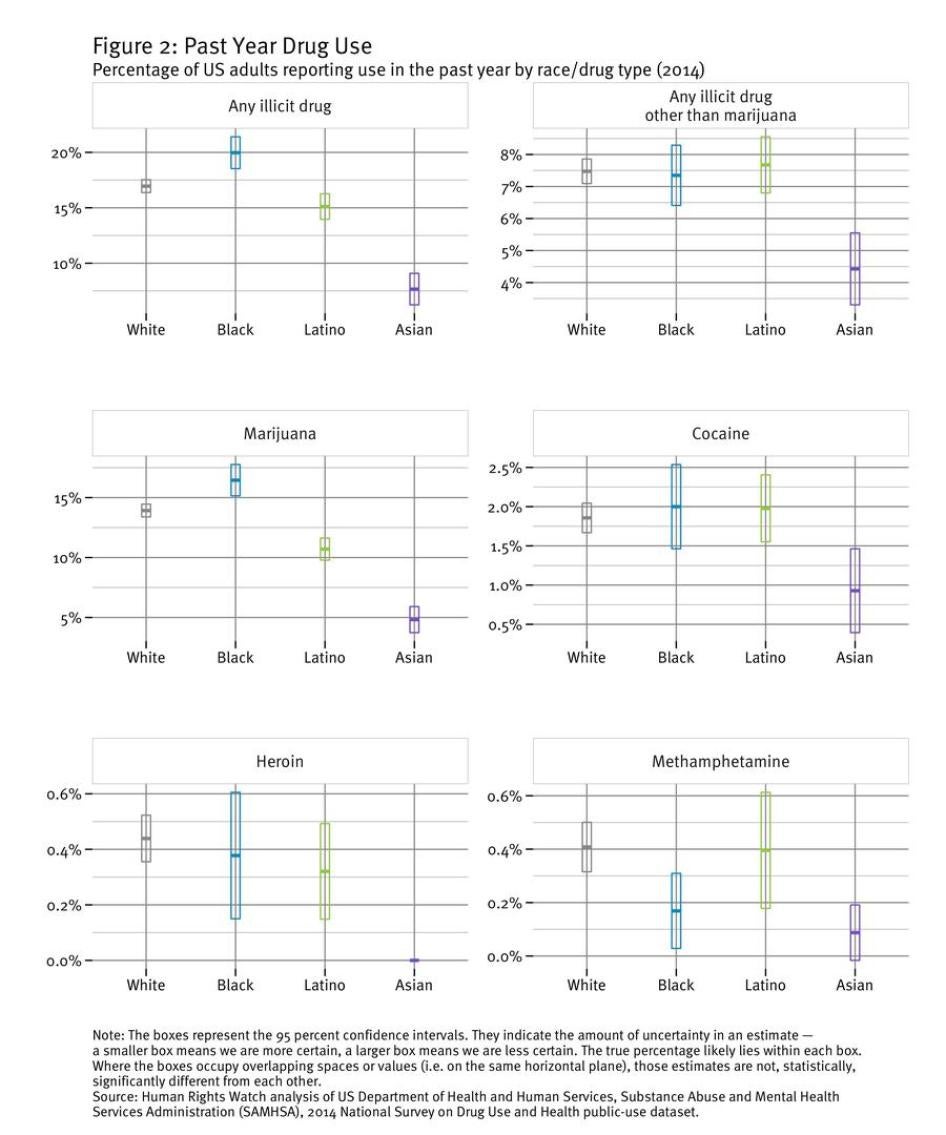

Over the course of their lives, white people are more likely than Black people to use illicit drugs in general, as well as marijuana, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines, and prescription drugs (for non-medical purposes) specifically. Data on more recent drug use (for example, in the past year) shows that Black and white adults use illicit drugs other than marijuana at the same rates and that they use marijuana at similar rates.

Yet around the country, Black adults are more than two-and-a-half times as likely as white adults to be arrested for drug possession. In 2014, Black adults accounted for just 14 percent of those who used drugs in the previous year but close to a third of those arrested for drug possession. In the 39 states for which we have sufficient police data, Black adults were more than four times as likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than white adults.[2]

In every state for which we have sufficient data, Black adults were arrested for drug possession at higher rates than white adults, and in many states the disparities were substantially higher than the national rate—over 6 to 1 in Montana, Iowa, and Vermont. In Manhattan, Black people are nearly 11 times more likely than white people to be arrested for drug possession.

Darius Mitchell, a Black man in his 30s, was among those targeted in Louisiana. He recounted his story to us as follows: Late one night in Jefferson Parish, Darius was driving home from his child’s mother’s house. An officer pulled him over, claiming he was speeding. When Darius said he was sure he was not, the officer said he smelled marijuana. He asked whether he could search, and Darius said no. Another officer and a canine came and searched his car anyway. They yelled, “Where are the pounds?” suggesting he was a marijuana dealer. The police never found marijuana, but they found a pill bottle in Darius’ glove compartment, with his child’s mother’s name on it. Darius said that he had driven her to the emergency room after an accident, and she had been prescribed hydrocodone, which she forgot in the car. Still, the officers arrested him and he was prosecuted for drug possession, his first felony charge. He faced up to five years in prison. Darius was ultimately acquitted at trial, but months later he remained in financial debt from his legal fees, was behind in rent and utilities bills, and had lost his cable service, television, and furniture. He still had an arrest record, and the trauma and anger of being unfairly targeted.

Small-Scale Drug Use: Prosecutions for Tiny Amounts

We interviewed over 100 people in Texas, Louisiana, Florida, and New York who were prosecuted for small quantities of drugs—in some cases, fractions of a gram—that were clearly for personal use. Particularly in Texas and Louisiana, prosecutors did more than simply pursue these cases—they often selected the highest charges available and went after people as hard as they could.

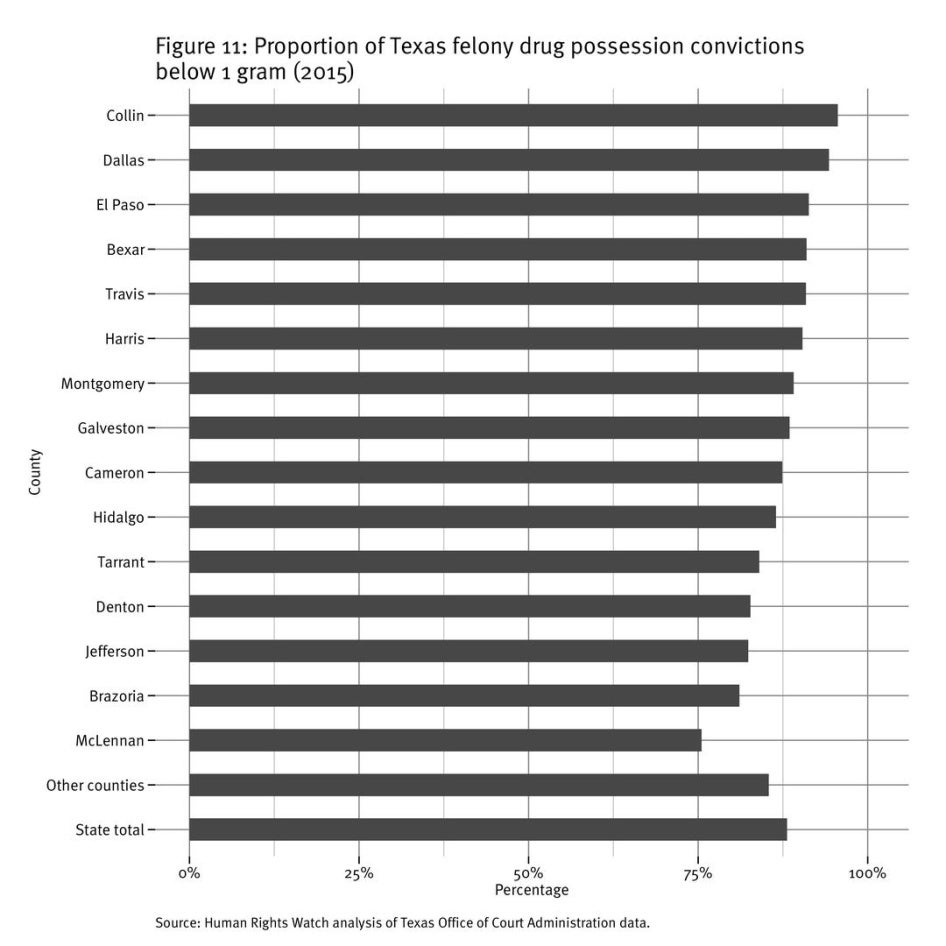

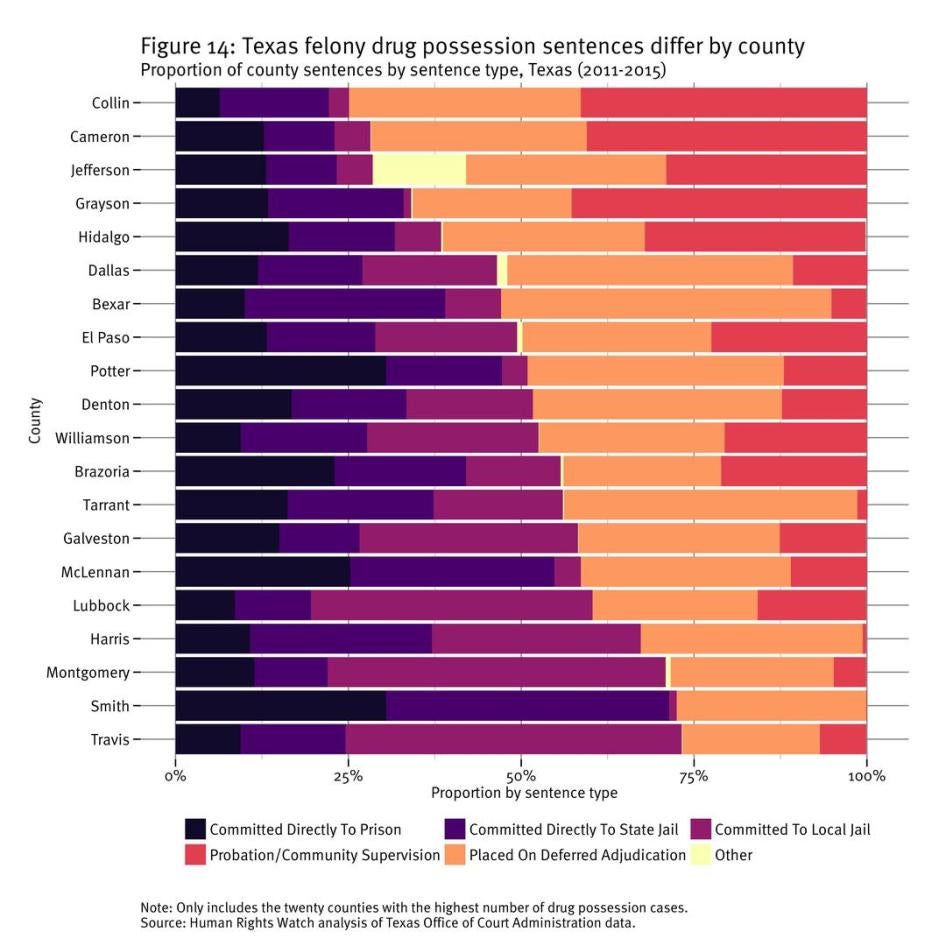

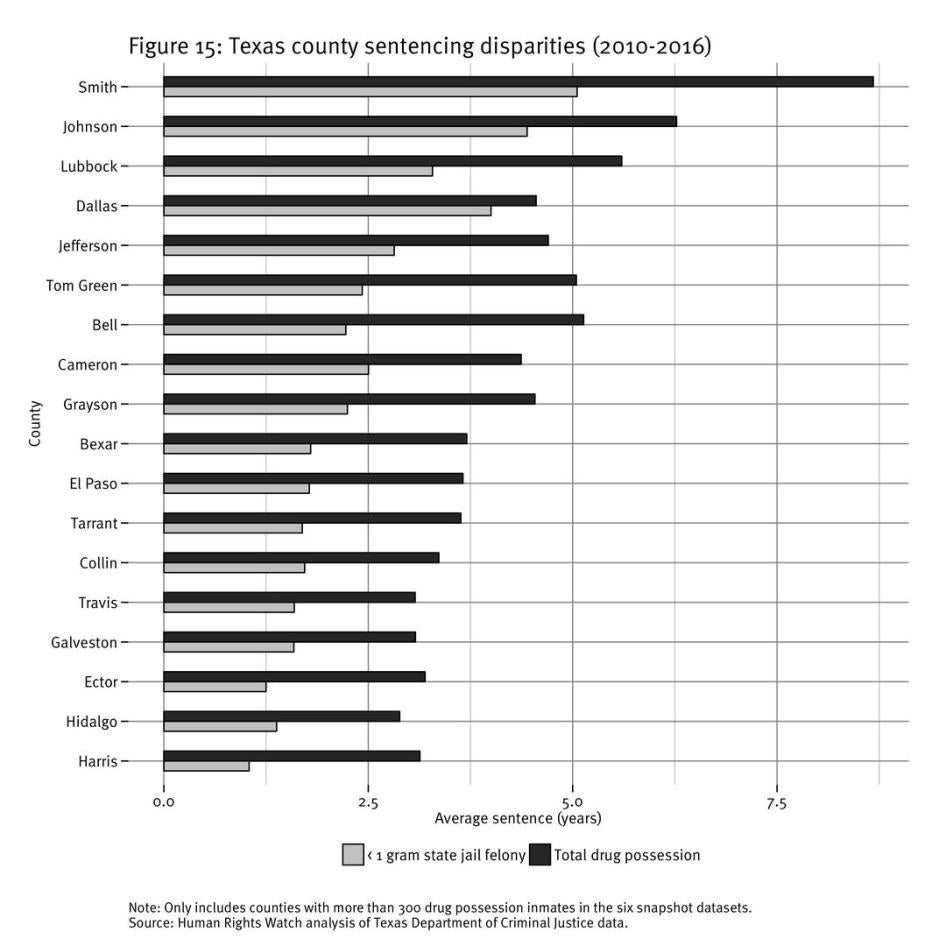

In 2015, according to data we analyzed from Texas courts, nearly 16,000 people were sentenced to incarceration for drug possession at the “state jail felony” level—defined as possession of under one gram of substances containing commonly used drugs, including cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, PCP, oxycodone, MDMA, mescaline, and mushrooms (or between 4 ounces and 5 pounds of marijuana).[3] One gram, the weight of less than one-fourth a sugar packet, is enough for only a handful of doses for new users of many drugs. Data presented here for the first time suggests that in 2015, more than 78 percent of people sentenced to incarceration for felony drug possession in Texas possessed under a gram. Possibly thousands more were prosecuted and put on probation, potentially with felony convictions. In Dallas County, the data suggests that nearly 90 percent of possession defendants sentenced to incarceration were for under a gram.

The majority of the 30 defendants we interviewed in Texas had substantially less than a gram of illicit drugs in their possession when they were arrested: not 0.9 or 0.8 grams, but sometimes 0.2, 0.02, or a result from the lab reading “trace,” meaning that the amount was too small even to be measured. One defense attorney in Dallas told us a client was charged with drug possession in December 2015 for 0.0052 grams of cocaine. The margin of error for the lab that tested it is 0.0038 grams, meaning it could have weighed as little as 0.0014 grams, or 35 hundred-thousandths (0.00035) of a sugar packet.

Bill Moore, a 66-year-old man in Dallas, is serving a three-year prison sentence for 0.0202 grams of methamphetamines. In Fort Worth, Hector Ruiz was offered six years in prison for an empty bag that had heroin residue weighing 0.007 grams. In Granbury, Matthew Russell was charged with possession of methamphetamines for an amount so small that the laboratory result read only “trace.” The lab technician did not even assign a fraction of a gram to it.

A System that Coerces Guilty Pleas

In 2009 (the most recent year for which national data is available), more than 99 percent of people convicted of drug possession in the 75 largest US counties pled guilty. Our interviews and data analysis suggest that in many cases, high bail—particularly for low-income defendants—and the threat of long sentences render the right to a jury trial effectively meaningless.

Data we obtained from Florida and Alabama reveals that, at least in those two states, the majority of drug possession defendants were poor enough to qualify for court-appointed counsel. Yet in 2009, drug possession defendants in the 75 largest US counties had an average bail of $24,000 (for those detained, average bail was $39,900). For lower-income defendants, such high bail often means they must remain in jail until their case is over.

For defendants with little to no criminal history, or in relatively minor cases, prosecutors often offer probation, relatively short sentences, or “time served.” For those who cannot afford bail, this means a choice between fighting their case from jail or taking a conviction and walking out the door. In Galveston, Texas, Breanna Wheeler, a single mother, pled to probation and her first felony conviction against her attorney’s advice. They both said she had a strong case that could be won in pretrial motions, but her attorney had been waiting months for the police records, and Breanna needed to return home to her 9-year-old daughter. In New York City, Deon Charles told us he pled guilty because his daughter had just been born that day and he needed to see her.

For others, the risk of a substantially longer sentence at trial means they plead to avoid the “trial penalty.” In New Orleans, Jerry Bennett pled guilty to possession of half a gram of marijuana and a two-and-a-half-year prison sentence, because he faced 20 years if he lost at trial: “They spooked me out by saying, ‘You gotta take this or you’ll get that.’ I’m just worried about the time. Imagine me in here for 20 years. They got people that kill people. And they put you up here for half a gram of weed.”

For the minority of people we interviewed who exercised their right to trial, the sentences they received in Louisiana and Texas were shocking. In New Orleans, Corey Ladd was sentenced as a habitual offender to 17 years for possessing half an ounce of marijuana. His prior convictions were for possession of small amounts of LSD and hydrocodone, for which he got probation both times. In Granbury, Texas, after waiting 21 months in jail to take his case to trial, Matthew Russell was sentenced to 15 years for a trace amount of methamphetamines. According to him and his attorney, his priors were mostly out-of-state and related to his drug dependence.

Incarceration for Drug Possession

At year-end 2014, over 25,000 people were serving sentences in local jails and another 48,000 were serving sentences in state prisons for drug possession nationwide. The number admitted to jails and prisons at some point over the course of the year was significantly higher. As with arrests, there were sharp racial disparities. In 2002 (the most recent year for which national jail data is available), Black people were over 10 times more likely than white people to be in jail for drug possession. In 2014, Black people were nearly six times more likely than white people to be in prison for drug possession.

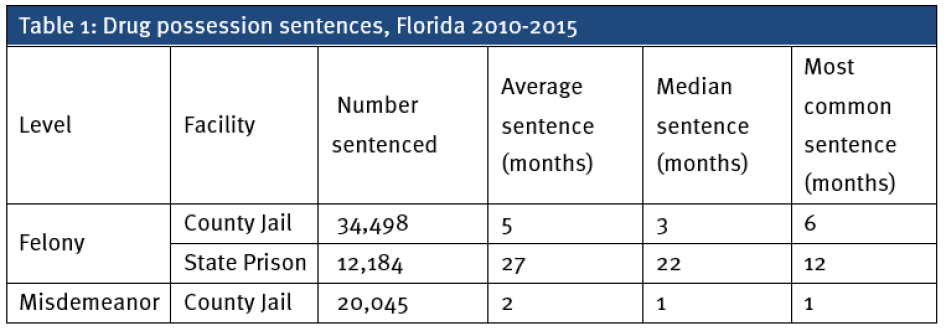

Our analysis of data from Florida, Texas, and New York, presented here for the first time, shows that the majority of people convicted of drug possession in these states are sentenced to some form of incarceration. Because each dataset is different, they show us different things. For example, our data suggests that in Florida, 75 percent of people convicted of felony drug possession between 2010 and 2015 had little to no prior criminal history. Yet 84 percent of people convicted of these charges were sentenced to prison or jail. In New York State, between 2010 and 2015, the majority of people convicted of drug possession were sentenced to some period of incarceration. At year-end 2015, one of sixteen people in custody in New York State was incarcerated for drug possession. Of those, 50 percent were Black and 28 percent Latino. In Texas, between 2012 and 2016, approximately one of eleven people in prison had drug possession as their most serious offense; two of every three people serving time for drug charges were there for drug possession; and 116 people had received life sentences for drug possession, at least seven of which were for an amount weighing between one and four grams.

For people we spoke to, the prospect of spending months or years in jail or prison was overwhelming. For most, the well-being of family members in their absence was also a source of constant concern, sometimes more vivid for them than the experience of jail or prison itself. Parents told us they worried about children growing up without them. Some described how they missed seeing their children but did not let them visit jail or prison because they were concerned the experience would be traumatizing. Others described the anguish of no-contact jail visits, where they could see and hear but not reach out and touch their young children’s hands. Some worried about partners and spouses, for whom their incarceration meant lost income and lost emotional and physical support.

In Covington, Louisiana, Tyler Marshall’s wife has a disability, and he told us his absence took a heavy toll. “My wife, I cook for her, clean for her, bathe her, clothe her…. Now everything is on her, from the rent to the bills, everything…. She’s behind [on rent] two months right now. She’s disabled and she’s doing it all by herself.” In New Orleans, Corey Ladd was incarcerated when his girlfriend was eight months pregnant. He saw his infant daughter Charlee for the first time in a courtroom and held her for the first time in the infamous Angola prison. She is four now and thinks she visits her father at work. “She asks when I’m going to get off work and come see her,” Corey told us. He is a skilled artist and draws Charlee pictures. In turn, Charlee brings him photos of her dance recitals and in the prison visitation hall shows him new dance steps she has learned. Corey, who is currently serving 17 years for marijuana possession, may never see her onstage.

Probation, Criminal Justice Debt, and Collateral Consequences

Even for those not sentenced to jail or prison, a conviction for drug possession can be devastating, due to onerous probation conditions, massive criminal justice debt, and a wide range of restrictions flowing from the conviction (known in the literature as “collateral consequences”).

Many defendants, particularly those with no prior convictions, are offered probation instead of incarceration. Although probation is a lesser penalty, interviewees in Florida, Louisiana, and Texas told us they felt “set up to fail” on probation, due to the enormous challenges involved in satisfying probation conditions (for example, frequent meetings at distant locations that make it impossible for probationers to hold down a job, but require that they earn money to pay for travel and fees). Some defense attorneys told us that probation conditions were so onerous and unrealistic that they would counsel clients to take a short jail or prison sentence instead. A number of interviewees said if they were offered probation again, they would choose incarceration; others said they knew probation would be too hard and so chose jail time.

At year-end 2014, the US Department of Justice reported that 570,767 people were on probation for drug law violations (the data does not distinguish between possession and sales), accounting for close to 15 percent of the entire state probation population around the country. In some states, drug possession is a major driver of probation. In Missouri, drug possession is by far the single largest category of felony offenses receiving probation, accounting for 9,500 people or roughly 21 percent of the statewide probation total. Simple possession is also the single largest driver in Florida, accounting for nearly 20,000 cases or 14 percent of the statewide probation total. In Georgia, possession offenses accounted for 17 percent of new probation starts in 2015 and roughly 16 percent of the standing probation population statewide at mid-year 2016.

In addition to probation fees (if they are offered probation), people convicted of drug possession are often saddled with crippling court-imposed fines, fees, costs, and assessments that they cannot afford to pay. These can include court costs, public defender application fees, and surcharges on incurred fines, among others. They often come on top of the price of bail (if defendants can afford it), income-earning opportunities lost due to incarceration, and the financial impact of a criminal record. For those who choose to hire an attorney, the costs of defending their case may have already left them in debt or struggling to make ends meet for months or even years to come.

A drug conviction also keeps many people from getting a job, renting a home, and accessing benefits and other programs they may need to support themselves and their families—and to enjoy full civil and social participation. Federal law allows states to lock people out of welfare assistance and public housing for years and sometimes even for life based on a drug conviction. People convicted of drug possession may no longer qualify for educational loans; they may be forced to rely on public transport because their driver’s license is automatically suspended; they may be banned from juries and the voting booth; and they may face deportation if they are not US citizens, no matter how many decades they have lived in the US or how many of their family members live in the country. In addition, they must bear the stigma associated with the labels of “felon” and “drug offender” the state has stamped on them, subjecting them to private discrimination in their daily interactions with landlords, employers, and peers.

A Call for Decriminalization

As we argue in this report, laws criminalizing drug use are inconsistent with respect for human autonomy and the right to privacy and contravene the human rights principle of proportionality in punishment. In practice, criminalizing drug use also violates the right to health of those who use drugs. The harms experienced by people who use drugs, and by their families and broader communities, as a result of the enforcement of these laws may constitute additional, separate human rights violations.

Criminalization has yielded few, if any, benefits. Criminalizing drugs is not an effective public safety policy. We are aware of no empirical evidence that low-level drug possession defendants would otherwise go on to commit violent crimes. And states have other tools at their disposal—for example, existing laws that criminalize driving under the influence or child endangerment—to address any harmful behaviors that may accompany drug use.

Criminalization is also a counterproductive public health strategy. Rates of drug use across drug types in the US have not decreased over the past decades, despite widespread criminalization. For people who struggle with drug dependence, criminalization often means cycling in and out of jail or prison, with little to no access to voluntary treatment. Criminalization undermines the right to health, as fear of law enforcement can drive people who use drugs underground, deterring them from accessing health services and emergency medicine and leading to illness and sometimes fatal overdose.

It is time to rethink the criminalization paradigm. Although the amount cannot be quantified, the enormous resources spent to identify, arrest, prosecute, sentence, incarcerate, and supervise people whose only offense has been possession of drugs is hardly money well spent, and it has caused far more harm than good. Some state and local officials we interviewed recognized the need to end the criminalization of drug use and to develop a more rights-respecting approach to drugs. Senior US officials have also emphasized the need to move away from approaches that punish people who use drugs.

Fortunately, there are alternatives to criminalization. Other countries—and even some US states with respect to marijuana—are experimenting with models of decriminalization that the US can examine to chart a path forward.

Ending criminalization of simple drug possession does not mean turning a blind eye to the misery that drug dependence can cause in the lives of those who use and of their families. On the contrary, it requires a more direct focus on effective measures to prevent problematic drug use, reduce the harms associated with it, and support those who struggle with dependence. Ultimately, the criminal law does not achieve these important ends, and causes additional harm and loss instead. It is time for the US to rethink its approach to drug use.

Key Recommendations

Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union call on federal and state legislatures to end the criminalization of the personal use of drugs and the possession of drugs for personal use.

In the interim, we urge government officials at the local, state, and federal levels to adopt the recommendations listed below. These are all measures that can be taken within the existing legal framework to minimize the imposition of criminal punishment on people who use drugs, and to mitigate the harmful collateral consequences and social and economic discrimination experienced by those convicted of drug possession and by their families and communities. At the same time, officials should ensure that education on the risks and potential harms of drug use and affordable, evidence-based treatment for drug dependence are available outside of the criminal justice system.

Until full decriminalization is achieved, public officials should pursue the following:

- State legislatures should amend relevant laws so that a drug possession conviction is never a felony and cannot be used as a sentencing enhancement or be enhanced itself by prior convictions, and so that no adverse collateral consequences attach by law for convictions for drug possession.

- Legislatures should allocate funds to improve and expand harm reduction services and prohibit public and private discrimination in housing or employment on the basis of prior drug possession arrests or convictions.

- To the extent permitted by law and by limits on the appropriate exercise of discretion, police should decline to make arrests for drug possession and should not stop, frisk, or search a person simply to find drugs for personal use. Police departments should not measure officer or department performance based on stop or arrest numbers or quotas and should incentivize and reward officer actions that prioritize the health and safety of people who use drugs.

- To the extent permitted by law and by limits on the appropriate exercise of discretion, prosecutors should decline to prosecute drug possession cases, or at a minimum should seek the least serious charge supported by the facts or by law. Prosecutors should refrain from prosecuting trace or residue cases and should never threaten enhancements or higher charges to pressure drug possession defendants to plead guilty. They should not seek bail in amounts they suspect defendants will be unable to pay.

- To the extent permitted by law and by limits on the appropriate exercise of discretion, judges should sentence drug possession defendants to non-incarceration sentences. Judges should release drug possession defendants on their own recognizance whenever appropriate; if bail is required, it should be set at a level carefully tailored to the economic circumstances of individual defendants.

- To the extent permitted by law and by limits on the appropriate exercise of discretion, probation officers should not charge people on probation for drug offenses with technical violations for behavior that is a result of drug dependence. Where a legal reform has decreased the sentences for certain offenses but has not made the decreases retroactive, parole boards should consider the reform when determining parole eligibility.

- The US Congress should amend federal statutes so that no adverse collateral consequences attach by law to convictions for drug possession, including barriers to welfare assistance and subsidized housing. It should appropriate sufficient funds to support evidence-based, voluntary treatment options and harm reduction services in the community.

- The US Department of Justice should provide training to state law enforcement agencies clarifying that federal funding programs are not intended to and should not be used to encourage or incentivize high numbers of arrests for drug possession, and emphasizing that arrest numbers are not a valid measure of law enforcement performance.

Methodology

This report is the product of a joint initiative—the Aryeh Neier fellowship—between Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union to strengthen respect for human rights in the United States.

The report is based on more than 365 in-person and telephone interviews, as well as data provided to Human Rights Watch in response to public information requests.

Between October 2015 and March 2016, we conducted interviews in Louisiana, Texas, Florida, and New York City with 149 people prosecuted for their drug use. Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union identified individuals who had been subjected to prosecution in those jurisdictions through outreach to service providers, defense attorneys, and advocacy networks as well as through observation of courtroom proceedings.

In New York City, the majority of our interviews were conducted at courthouses or at the site of harm reduction and reentry programs. In Florida, Louisiana, and Texas, we met interviewees at detention facilities, drug courts, harm reduction and reentry programs, law offices, and restaurants in multiple counties.

In the three southern states, we conducted 64 interviews with people who were in custody—in local jails, state prisons, department of corrections work release or trustee facilities, and courthouse lock-ups across 13 jurisdictions. Within the jails and prisons, interviews took place in an attorney visit room to ensure confidentiality.

Most interviews were conducted individually and in private. Group interviews were conducted with three families and with participants in drug court programs in New Orleans (in drug court classrooms) and St. Tammany Parish (in a private room in the courthouse). All individuals interviewed about their experience provided informed consent, and no incentive or remuneration was offered to interviewees. For interviewees with pending charges, we interviewed them only with approval from their attorney and did not ask any questions about disputed facts or issues. In those cases, we explained to interviewees that we did not want them to tell us anything that could be used against them in their case.

To protect the privacy and security of these interviewees, a substantial number of whom remain in custody, we decided to use pseudonyms in all but two cases. In many cases, we also withheld certain other identifying information. Upon their urging and because of unique factors in their cases, we have not used pseudonyms for Corey Ladd and Byron Augustine in New Orleans and St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana, respectively.

In addition, we conducted 23 in-person interviews with current or former state government officials, including judges, prosecutors, law enforcement, and corrections officers. We also had phone interviews and/or correspondence with US Department of Justice officials and additional state prosecutors. We interviewed nine family members of people currently in custody, as well as 180 defense attorneys, service providers (including those working for harm reduction programs such as syringe exchanges, voluntary treatment programs, and court-mandated treatment programs), and local and national advocates.

Where attorneys introduced us to clients with open cases, we reviewed court documents wherever possible and corroborated information with the attorney. In other cases, we also reviewed case files provided by defendants or available to the public online. However, because of the sheer number of interviews we conducted, limited public access to case information in some jurisdictions, and respect for individuals’ privacy, we did not review case information or contact attorneys for all interviewees. We also could not seek the prosecutor’s perspective on specific cases because of confidentiality. We therefore present people’s stories mostly as they and their attorneys told them to us.[4]

Human Rights Watch submitted a series of data requests regarding arrests, prosecutions, case outcomes, and correctional population for drug offenses to a number of government bodies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and various state court administrations, statistical analysis centers, sentencing commissions, departments of correction, clerks of court, and other relevant entities. We chose to make data requests based on which states had centralized systems and/or had statutes or criminal justice trends that were particularly concerning. Attempts to request data were made through email, facsimile, and/or phone to one or more entities in the following states: Alabama, California, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, New York, Oklahoma, Texas, and Wisconsin. Among those, the FBI, Alabama Sentencing Commission, Florida Office of State Court Administrator, New York Division of Criminal Justice Services, New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, Texas Department of Criminal Justice, and Texas Office of Court Administration provided data to us.[5] Because of complications with the data file the FBI provided to us, we used the same set of data provided to and organized by the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research.[6] We also analyzed data available online from the US Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics and some state agencies.

As this report was going to press, the FBI released aggregated 2015 arrest data. We have used this 2015 data to update all nationwide arrest estimates for drug possession and other offenses in this report. However, for all state-by-state arrest and racial disparities analyses, we relied on 2014 data, as these analyses required disaggregated data as well as data from non-FBI sources and 2014 remained the most recent year for which such data was available.

Although the federal government continues to criminalize possession of drugs for personal use, in practice comparatively few federal prosecutions are for possession. This report therefore focuses on state criminalization, although we call for decriminalization at all levels of government.

A note on state selection:

We spent a month at the start of this project defining its scope and selecting states on which we would focus, informed by phone interviews with legal practitioners and state and national advocates, as well as extensive desk research. We chose to highlight Louisiana, Texas, Florida, and New York because of a combination of problematic laws and enforcement policies, availability of data and resources, and positive advocacy opportunities.

This report focuses on Louisiana because it has the highest per capita imprisonment rate in the country and because of its problematic application of the state habitual offender law to drug possession, resulting in extreme sentences for personal drug use. The report focuses on Texas because of extensive concerns around its pretrial detention and jail system, its statutory classification of felony possession by weight, and its relatively softer treatment of marijuana possession as compared to other drugs. We also emphasize the potential for substantial criminal justice reform in both states—which stakeholders and policymakers are already considering—and the opportunity for state officials at all levels to set an example for others around the country.

While this report focuses more heavily on Louisiana and Texas, we draw extensively from data and interviews in Florida and New York. We selected Florida because of its experience with prescription painkiller laws and the codification of drug possession over a certain weight as “trafficking.” We selected New York as an example of a state in which low-level (non-marijuana) drug possession is a misdemeanor and does not result in lengthy incarceration, and yet criminalization continues to be extremely disruptive and harmful to those who use drugs and to their broader communities. New York shows us that reclassification of drug possession from a felony to a misdemeanor, while a positive step, is insufficient to end the harms of criminalization, especially related to policing and arrests.

As described in the Background section, all states criminalize drug possession, and the majority make it a felony offense. As our data shows, most if not all states also arrest in high numbers for drug possession and do so with racial disparities. Thus, although we did not examine the various stages of the criminal process in more than these four states, we do know that the front end (the initial arrest) looks similar in many states. It is likely, as people move through the criminal justice system, that many of the problems that we documented in New York, Florida, Texas, and Louisiana are also experienced to varying degrees in other states. At the same time, there may be additional problems in other states that we have not documented. Wherever possible throughout the report, we draw on data and examples from other states and at the national level.

We are grateful to officials in Texas, Florida, and New York for their transparency in providing us remarkable amounts of data at no cost.[7] We regret our inability to obtain data from Louisiana. For 15 of Louisiana’s 41 judicial districts, plus the Orleans Criminal District Court, we made data requests to the clerk of court by phone, email, and/or facsimile. None was able to provide the requested information, and those who responded said they did not retain such data.

A note on terminology:

Although most states have a range of offenses that criminalize drug use, this report focuses on criminal drug possession and drug paraphernalia as the most common offenses employed to prosecute drug use (other offenses in some states include, for example, ingestion or purchase of a drug). Our position on decriminalization—and the harm wrought by enforcement of drug laws—extends more broadly to all offenses criminalizing drug use.

When we refer to “drug possession” in this report, we mean possession of drugs for personal use, as all state statutes we are aware of do. Like legal practitioners and others, we sometimes refer to it synonymously as “simple possession.” Possession of drugs for purposes other than personal use, such as for distribution, is typically noted as such in laws and conversation (for example, “possession with intent to distribute,” which we discuss in this report as well).

Not all drugs are criminalized: many substances are regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but are not considered “controlled substances” subject to criminalization. This report is about “illicit drugs” as they are understood in public discourse, the so-called “war on drugs,” and state and federal laws such as the Controlled Substances Act.[8] For simplicity, however, when we refer to “drugs” in this report, we mean illicit drugs.

Many people who use drugs told us the language of addiction was stigmatizing to them, whether or not they were dependent on drugs.[9] Because drug dependence is a less stigmatizing term, we used it where appropriate in our interviews and in this report to discuss the right to health implications of governments’ response to drug use and interviewees’ self-identified conditions. In so doing, we relied upon the definition of substance dependence as laid out in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) (also known as DSM-IV). Factors for a diagnosis of dependence under DSM-IV focus on individuals’ loss of ability to control their drug use.[10]

I. The Human Rights Case for Decriminalization

Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union oppose the criminalization of personal use of drugs and possession of drugs for personal use. We recognize that governments have a legitimate interest in preventing societal harms caused by drugs and in criminalizing harmful or dangerous behavior, including where that behavior is linked to drug use. However, governments have other means beyond the criminal law to achieve those ends and need not pursue a criminalization approach, which violates basic human rights and, as this report documents, causes enormous harm to individuals, families, and communities.

On their face, laws criminalizing the simple possession or use of drugs constitute an unjustifiable infringement of individuals’ autonomy and right to privacy. The right to privacy is broadly recognized under international law, including in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights[11] and the American Convention on Human Rights.[12] Limitations on the right to privacy, and more broadly on an individual’s autonomy, are only justifiable if they serve to advance a legitimate purpose; if they are both proportional to and necessary to achieve that purpose; and if they are non-discriminatory. Criminalizing drug use fails this test.

Governments and policymakers have long argued that laws criminalizing drug use are necessary to protect public morals;[13] to deter problematic drug use and its sometimes corrosive effects on families, friends, and communities; to reduce criminal behavior associated with drugs;[14] and to protect drug users from harmful health consequences.[15]

While these are legitimate government concerns, criminalization of drug possession does not meet the other criteria. It is not proportional or necessary to achieve those government goals and is often implemented in discriminatory ways. Indeed, it has not even proven effective: more than four decades of criminalization have apparently had little impact on the demand for drugs or on rates of use in the United States.[16] Criminalization can also undermine the right to health of those who use.[17]

Instead, governments have many non-penal options to reduce harm to people who use drugs, including voluntary drug treatment, social support, and other harm reduction measures. Criminalization of drug use is also not necessary to protect third parties from harmful actions performed under the influence of drugs, and the notion that harmful or criminal conduct is an inevitable result of drug use is a fallacy.[18] Governments can and do criminalize negligent or dangerous behavior (such as driving under the influence or endangering a child through neglect) linked to drug use, without criminalizing drug use itself. This is precisely the approach US laws take with regard to alcohol consumption.

Those who favor criminalization of drug use often emphasize harms to children. While governments have important obligations to take appropriate measures—legislative, administrative, social, and educational—to protect children from the harmful effects of drug use,[19] imposing criminal penalties on children for using or possessing drugs is not the answer. States should not criminalize adult drug use on the grounds that it protects children from drugs.

Worldwide, the practical realities of governments’ efforts to enforce criminal prohibitions on drug use have greatly compounded the urgent need to end those prohibitions. Criminalization has often gone hand-in-hand with widespread human rights violations and adverse human rights impacts—while largely failing to prevent the possession or use of drugs.[20] And rather than protecting health, criminalization of drug use has in fact undermined it.[21]

These grim realities are on stark display in the United States. This report describes the staggering human rights toll of drug criminalization and enforcement in the US. Not only has the government’s “war on drugs” failed on its own terms, but it has needlessly ruined countless lives through the crushing direct and collateral impacts of criminal convictions, while also erecting barriers that stand between people struggling with drug dependence and the treatment they may want and need.

In the United States the inherent disproportionality of criminalizing drug use has been greatly amplified by abusive laws. Sentences imposed across the US for drug possession are often so excessive that they would amount to disproportionate punishment in violation of human rights law even if criminalization were not per se a human rights problem.[22] In many US states these excessive sentences take the form of lengthy periods of incarceration (especially when someone is sentenced as a “habitual offender” for habitual drug use), onerous probation conditions that many interviewees called a set-up for failure, and sometimes crippling fines and fees.[23]

This report also describes a range of other human rights violations and harms experienced by people who use drugs and by entire families and communities as a result of criminalization, in addition to the punishments imposed by law. For instance, enforcement of drug possession laws has a discriminatory racial impact at multiple stages of the criminal justice process, beginning with selective policing and arrests.[24] In addition, enforcement of drug possession laws unfairly burdens the poor at almost every step of the process, from police encounters, to pretrial detention, to criminal justice debt and collateral consequences including exclusion from public benefits, again raising questions about equal protection rights.[25]

Many of the problems described in this report are not unique to drug cases; rather, they reflect the broader human rights failings of the US criminal justice system. That fact serves only to underscore the practical impossibility of addressing these problems through incremental changes to the current criminalization paradigm. It also speaks to the urgency of removing drug users—people who have engaged in no behavior worthy of criminalization—from a system that is plagued with broader and deeply entrenched patterns of human rights abuse and discrimination.

Rather than criminalizing drug use, governments should invest in harm reduction services and public education programs that accurately convey the risks and potential harms of drug use, including the potential to cause drug dependence. Harm reduction is a way of preventing disease and promoting health that “meets people where they are” rather than making judgments about where they should be in terms of their personal health and lifestyle.[26] Harm reduction programs focus on limiting the risks and potential harms associated with drug use and on providing a gateway to drug treatment for those who seek it.

Implementing harm reduction practices widely is not just sound public health policy; it is a human rights imperative that requires strong federal and state leadership.[27] The federal government has taken some important steps to promote harm reduction,[28] as have some state and local entities.[29]

However, the continued focus on criminalization of drug use—and the aggressiveness with which that is pursued by many public officials—runs counter to harm reduction. This report calls for a radical shift away from criminalization, towards health and social support services. Human rights principles require it.

II. Background

The “War on Drugs”

For four decades, federal and state measures to battle the use and sale of drugs in the US have emphasized arrest and incarceration rather than prevention and treatment. Between 1980 and 2015, arrests for drug offenses nearly tripled, rising from 580,900 arrests in 1980 to 1,488,707 in 2015.[30] Of those total arrests, the vast majority (78 percent in 1980 and 84 percent in 2015) have been for possession.[31]

Yet drug possession was not always criminalized. For much of the 19th century, opiates and cocaine were largely unregulated in the US. Regulations began to be passed towards the end of the 19th and at the start of the 20th century—a time when the US also banned alcohol. Early advocates for prohibitionist regimes relied on moralistic arguments against drug and alcohol use, along with concerns over health and crime. But many experts also point to the racist roots of early prohibitionist efforts, as certain drugs were associated in public discourse with particular marginalized races (for example, opium with Chinese immigrants).[32]

The US has also been a major proponent of international prohibition, and helped to push for the passage of the three major international drug control conventions beginning in the 1960s.[33] The purpose of the conventions was to combat drug abuse by limiting possession, use, and distribution of drugs exclusively to medical and scientific purposes and by implementing measures against drug trafficking through international cooperation.[34]

In 1971, President Richard Nixon announced that he was launching a “war on drugs” in the US, dramatically increasing resources devoted to enforcing prohibitions on drugs, using the criminal law. He proclaimed, “America’s public enemy number one in the United States is drug abuse. In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive.”[35] There are reasons to believe that the declaration of the “war on drugs” was more political in nature than a genuine response to a public health problem.[36]

Over the next decade, the “war on drugs” combined with a larger “tough on crime” policy approach, whose advocates believed harsh mandatory punishments were needed to restore law and order to the US. New laws increased the likelihood of a prison sentence even for low-level offenses, increased the length of prison sentences, and required prisoners to serve a greater proportion of their sentences before any possibility of review. These trends impacted drug offenses as well as other crimes.[37]

The new drug laws contributed to a dramatic rise in the prison population.[38] Between 1980 and 2003 the number of drug offenders in state prisons grew twelvefold.[39] By 2014, an estimated 208,000 men and women were serving time in state prisons for drug offenses, constituting almost 16 percent of all state prisoners.[40] Few of those entering prison because of drug offenses were kingpins or major traffickers.[41] A substantial number were convicted of no greater offense than personal drug use or possession. In 2014, nearly 23 percent of those in state prisons for drug offenses were incarcerated simply for drug possession.[42] Because prison sentences for drug possession are shorter than for sales, rates of admission are even more telling: in 2009 (the most recent year for which such data is available), about one third of those entering state prisons for drug offenses (for whom the offense was known) were convicted of simple drug possession.[43]

Drug Use in the United States

More than half of the US adult population report having used illicit drugs at some point in their lifetime, and one in three adults reports having used a drug other than marijuana.[44]

The US Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) conducts an annual survey of nearly 70,000 Americans over the age of 12 to produce the standard data used to research drug use. According to SAMHSA, 51.8 percent of adults reported lifetime use in 2014.[45] Moreover, 16.6 percent of the adult population had used illicit drugs in the past year, while one in ten had used such drugs in the past month.[46]

Lifetime rates of drug use are highest among white adults for all drugs in total, and for specific drugs such as marijuana, cocaine (including crack), methamphetamine, and non-medical use of prescription drugs. Latino and Asian adults use most drugs at substantially lower rates.[47]

For more recent drug use, for example use in the past year, Black, white, and Latino adults use drugs other than marijuana at very similar rates. For marijuana, 16 percent of Black adults reported using in the past year compared to 14 percent of white adults and about 11 percent of Latino adults:

State Drug Possession Laws

All US states currently criminalize the possession of illicit drugs.[48] Different states have different statutory schemes, choosing between misdemeanors and felonies, making distinctions based on type and/or quantities of drugs, and sometimes treating second or subsequent offenses more harshly. State sentences range from a fine, probation, or under one year in jail for misdemeanors, up to a lengthy term in prison—for example, 10 or 20 years—for some felony possession offenses or, when someone is sentenced under some states’ habitual offender laws, potentially up to life in prison.

While some states have decriminalized possession of small amounts of marijuana, other states still make marijuana possession a misdemeanor or even a felony.[49] No state has decriminalized possession of drugs other than marijuana. As to “schedule I and II” drugs (which include heroin, cocaine, methamphetamines, and most commonly known illicit drugs), eight states and the District of Columbia treat possession of small amounts a misdemeanor, including New York.[50] In the remaining 42 states, possession of small amounts of most illicit drugs other than marijuana is either always or sometimes a felony offense.[51]

In addition to the “convicted felon” label, many felony possession laws provide for lengthy sentences. Of the states we visited, Florida, Louisiana, and Texas classify possession of most drugs other than marijuana as a felony, no matter the quantity, and provide for the following sentencing ranges.

In Florida, simple possession of most drugs carries up to five years in prison.[52] Florida drug trafficking offenses are based simply on quantity triggers: simple possession can be enough, without any evidence of trafficking other than the quantity.[53] In Louisiana, possession of most drugs other than heroin carries up to five years in prison, and heroin carries a statutory minimum of four years in prison, up to a possible ten years.[54] In Texas, possession of under a gram of substances containing commonly known drugs including cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, PCP, oxycodone, MDMA, mescaline, and mushrooms (or between four ounces and five pounds of marijuana) carries six months to two years. One to four grams carries two to ten years.[55] Texas judges may order the sentence to be served in prison or may suspend the sentence and require a term of probation instead.

On top of these baseline ranges, some states allow prosecutors to enhance the sentence range for drug possession by applying habitual offender laws that treat defendants as more culpable—and therefore deserving of greater punishment—because they have prior convictions. For example, in Louisiana a person charged with drug possession who has one or two prior felony convictions faces up to 10 years in prison. With three prior felony convictions, a person charged with drug possession faces a mandatory minimum of 20 years to life in prison.[56] In Texas, a person with two prior felony convictions who is charged with possession of one to four grams of drugs faces 25 years to life.[57]

In 2009 (the most recent year for which such data is available), 50 percent of people arrested for felony possession offenses in the 75 largest US counties had at least one prior felony conviction, mostly for non-violent offenses.[58] Thus the scope of potential application of the habitual offender laws to drug possession cases is extensive for states that employ them.[59]

III. The Size of the Problem: Arrests for Drug Use Nationwide

Possession Arrests by the Numbers

Across the United States, police make more arrests for drug possession than for any other crime. Drug possession accounts for more than one of every nine arrests by state law enforcement agencies around the country.[60]

Although all states arrest a significant number of people for drug possession each year, police focus on it more or less heavily in different states. For example, in California, one of every six arrests in 2014 was for drug possession, while in Alaska the rate was one of every 27.[61]

In 2015, state law enforcement agencies made more than 1.25 million arrests for drug possession—and because not all agencies report data, the true number of arrests is higher.[62] Even this estimate reveals a massive problem: 1.25 million arrests translates into an arrest for drug possession every 25 seconds of each day.[63]

Some states arrest significantly more people for drug possession than other states:

While the bulk of drug possession arrests are in large states such as California, Texas, and New York, the list of hardest-hitting states looks different when mapped onto population size. Maryland, Nebraska, and Mississippi have the highest per capita drug possession arrest rates. For comparison, the rate of arrest for drug possession ranged from 700 per 100,000 people in Maryland to 77 per 100,000 in Vermont:

The differences in drug arrest rates at the state level are all the more striking because drug use rates are fairly consistent across the country. SAMHSA data shows that about 3 percent of US adults used an illicit drug other than marijuana in the past month.[64] There is little variation at the state level, where past month use ranges from about 2 percent in Wyoming to a little over 4 percent in Colorado. For marijuana, there is slightly greater variation. About 8 percent of US adults used marijuana in the past month, but this ranged from about 5 percent in South Dakota to 15 percent in Colorado.[65]

While many public officials told us drug law enforcement is meant to get dealers off the streets, the vast majority of people arrested for drug offenses are charged with nothing more than possessing a drug for their personal use.[66] For every person arrested for selling drugs in 2015, four were arrested for possessing or using drugs—and two of those four were for marijuana possession.[67]

Despite shifting public opinion on marijuana, about half of all drug possession arrests are for marijuana.[68] In 2015, there were over 574,640 arrests just for marijuana possession.[69] By comparison, there were 505,681 arrests for violent crimes (which the FBI defines as murder, non-negligent manslaughter, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault). This means that police made almost 14 percent more arrests for simple marijuana possession than for all violent crimes combined.[70]

Some police told us that they have to make an arrest if they see unlawful conduct, but this glosses over the key question of where and upon whom the police are focusing their attention to begin with. Differences in arrest rates for drug possession within a state reveal that individual police departments have substantial discretion in how they enforce the law, resulting in stark contrasts. For example, data provided to us by Texas shows that 53 percent of drug possession arrests in Harris County (in and around Houston) were for marijuana, compared with 39 percent in nearby Dallas County.[71] Yet a nearly identical proportion of both counties’ populations used drugs in the past year.[72]

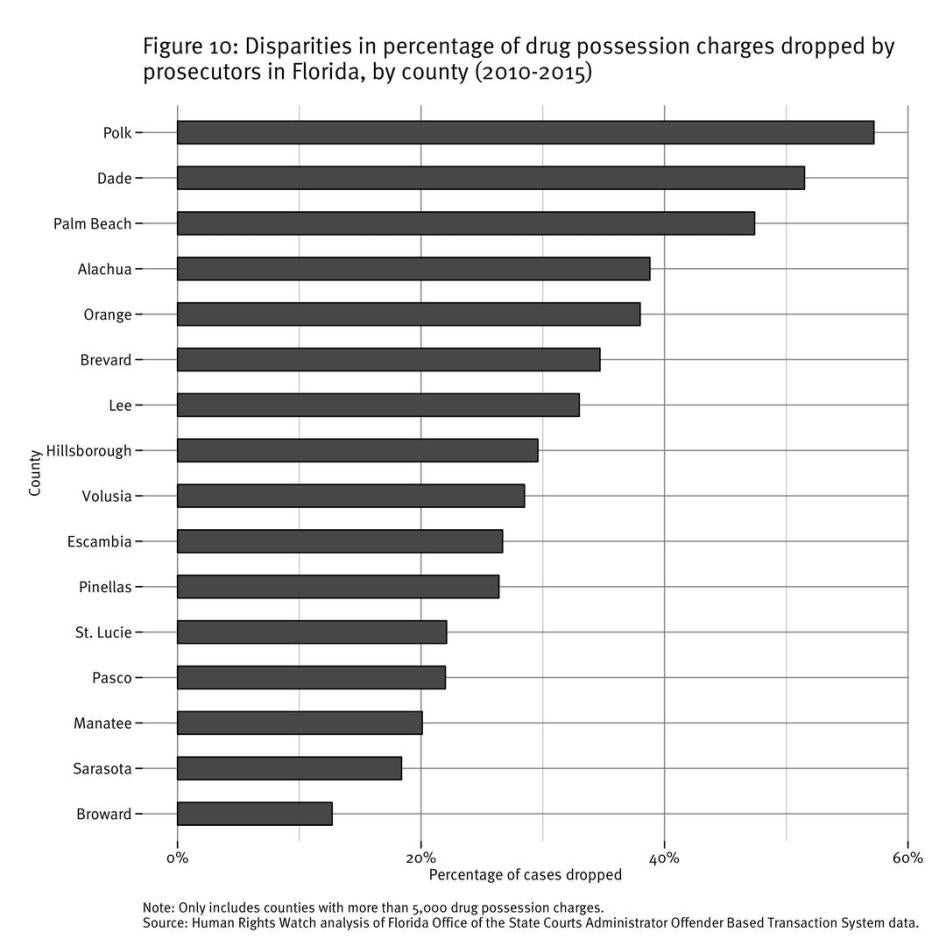

Additionally, certain jurisdictions within a state place a stronger focus on policing drug possession. In New York State, the counties with the highest drug possession arrest rates by a large margin were all in and around urban areas of New York City and Buffalo.[73] In Florida, the highest rates of arrest were spread around the state in rural Bradford County, urban Miami-Dade County, Monroe County (the Keys), rural Okeechobee County, and urban Pinellas County.[74] Within both states, drug use rates vary little between regions.[75]

In Texas, the counties with the highest drug possession arrest rates are all small rural counties. Kenedy County, for example, has an adult population of 407 people, yet police there made 329 arrests for drug possession between 2010 and 2015.[76]

Racial Disparities

Rather than stumbling upon unlawful conduct, when it comes to drug use and possession, police often aggressively search it out—and they do so selectively, targeting low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. As criminal justice practitioners, social science experts, and the US public now recognize all too well, racially disparate policing has had devastating consequences.[77]

Research has consistently shown that police target certain neighborhoods for drug law enforcement because drug use and drug sales occur on streets and in public view. Making arrests in these neighborhoods is therefore easier and less resource-intensive.

Comparably few of the people arrested in these areas are white.[78] Harrison Davis, a young Black man who was charged with possession of cocaine in Shreveport, Louisiana, recalled how the arresting officer had defended what Harrison considered racial profiling[79] during a preliminary examination: “‘I pulled him over because he was in a well-known drug area,’ the police officer says to the judge. But I’ve been living there for 27 years. It’s nothing but my family.”[80]

Black adults are more than two-and-a-half times as likely as white adults to be arrested for drug possession in the US.[81] In 2014, Black people accounted for just 14 percent of people who used drugs in the previous year, but close to a third of those arrested for drug possession.[82] In the 39 states for which we have sufficient police data, Black adults were more than four times as likely to be arrested for marijuana possession as white adults.[83]

The disparities in absolute numbers or rates of arrests cannot be blamed on a few states or jurisdictions. While numerous studies have found racial disparities in marijuana arrests,[84] analyses of state- and local-level data provided to Human Rights Watch show consistent disparities across the country for all drugs, not just marijuana.

In every state for which we have sufficient police data, Black adults were arrested for drug possession at higher rates than white adults, and in many states the disparities were substantially higher than the national rate—over 6 to 1 in Montana, Iowa, and Vermont.[85]

These figures likely underestimate the racial disparity nationally, because in three states with large Black populations—Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama—an insufficient proportion of law enforcement agencies reported data and thus we could not include them in our analysis.

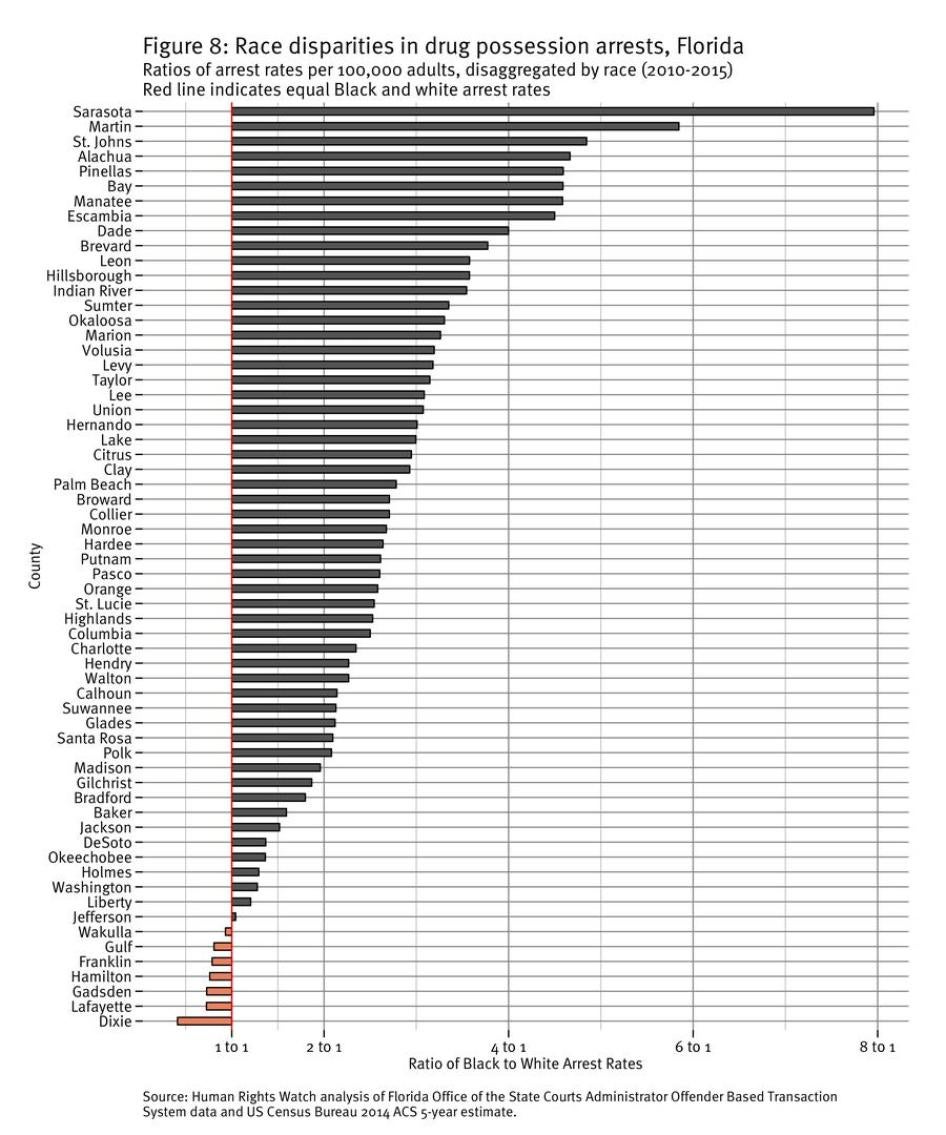

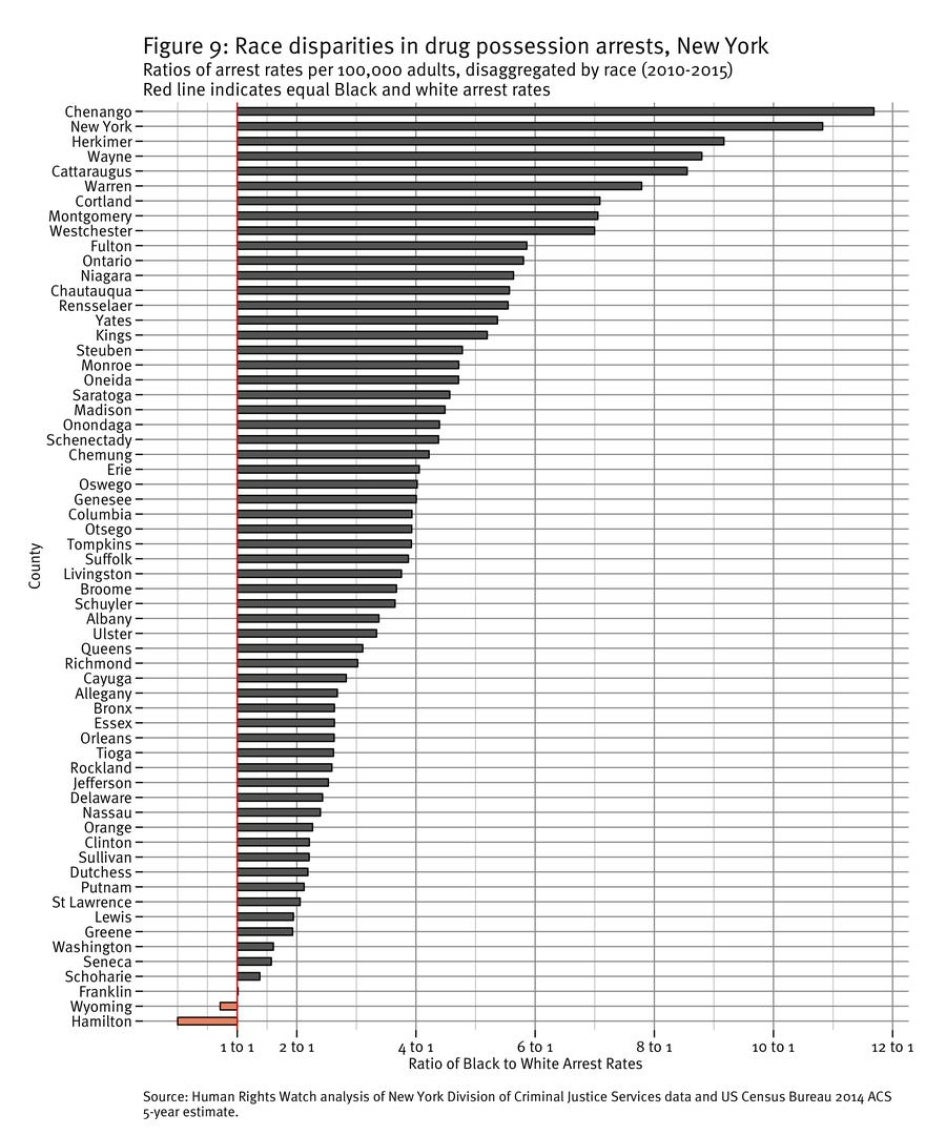

Our in-depth analysis of Florida and New York data show that disparities are not isolated to a few municipalities or urban centers, though they are considerably starker in some localities than in others.

In Florida, 60 of 67 counties arrested Black people for drug possession at higher rates than white people.[86] In Sarasota County, the ratio of Black to white defendants facing drug possession charges was nearly 8 to 1 when controlling for population size. Down the coast in comparably sized Collier County, the ratio, while still showing a disparity, was less than 3 to 1.

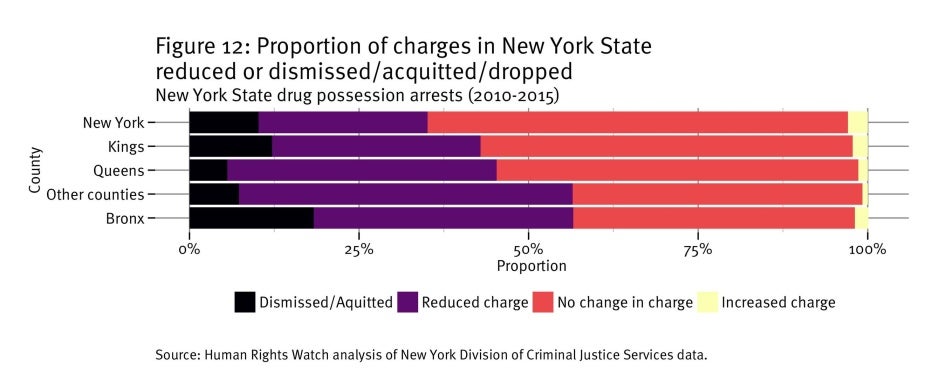

In New York, 60 of 62 counties arrested Black people for drug possession at higher rates than white people.[87] In Manhattan (New York County), there were 3,309 arrests per 100,000 Black people compared to 306 per 100,000 white people between 2010 and 2015. In other words, Black people in Manhattan were nearly 11 times more likely than white people to be arrested for drug possession.

Under international human rights law, prohibited racial discrimination occurs where there is an unjustifiable disparate impact on a racial or ethnic group, regardless of whether there is any intent to discriminate against that group.[88] Enforcement of drug possession laws in the US reveals stark racial disparities that cannot be justified by disparities in rates of use.

Incentives for Drug Arrests

Department cultures and performance metrics that incentivize high numbers of arrests may drive up the numbers of unnecessary drug arrests and unjustifiable searches in some jurisdictions.

In some cases, department culture may suggest to individual officers that the way to be successful and productive, and earn promotions, is to have high arrest numbers. In turn, a focus on arrest numbers may translate into an emphasis on drug arrests, because drug arrests are often easier to obtain than arrests for any other type of offense, especially if certain neighborhoods are targeted. As Randy Smith, former Slidell Chief of Police and current Sheriff for St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana, told us,

[Suppose I say,] “I want you to go out there and bring me in [more arrests]. Your numbers are down, last month you only had 10 arrests, you better pick that up or else I’m going put you in another unit.” You’re going to go out there and do what? You’re going [to go] out there to make drug arrests.[89]

Although the practice is outlawed in several states, some police departments operate a system of explicit or implicit arrest quotas.[90] Whether arrest numbers are formalized into quotas or understood as cultural expectations of a department, they may put some officers under immense pressure not only to make regular stops and arrests but to match or increase their previous numbers, in order to be seen as adequately “productive.”[91] In August 2015, twelve New York Police Department officers filed a class-action lawsuit against the department for requiring officers to meet monthly arrest and summons quotas, with one plaintiff noting that after being told he was “dragging down the district’s overall arrest rate,” he was given more undesirable job assignments.[92] In an Alabama town, an officer claimed in 2013 to have been fired after publicly criticizing the police department’s new ticket quota directives, which included making roughly 72,000 contacts (including arrests, tickets, warnings, and field interviews) per year in a town of 50,000 people.[93]

Such departmental pressure to meet arrest quotas can easily lead to more arbitrary stops and searches. In the aftermath of Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri, the US Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division recommended that the Ferguson Police Department change its stop and search policies in part by prohibiting “the use of ticketing and arrest quotas, whether formal or informal,” and focus instead on community protection.[94]

Randy Smith told us he opposes putting “expectations” or quotas on officers. “It kills you,” he explained:

I think sometimes you start building numbers and stats, and you kind of lose the ability to make better decisions on getting someone help, [when] getting a stat is putting them in jail. I’ve been there, and I’ve seen. You start having some serious problems.[95]

He said when officers understand that they are expected to make high arrest numbers, they often focus on drug possession:

So you’re going to stop 10 cars in maybe a not so good neighborhood. Out of 10 cars, you might get one out of those 10 that you get some dope or marijuana or a joint in the ash tray, or a Xanax in your purse…. If you dump [any] purse out, there’s probably some kind of anti-depression medicine in there, which is a felony [potentially]. And we know it, we’ve seen it, where those street crime guys will get out there and bring you to jail on a felony for a schedule four without a prescription, just because they got a stat. They’re tying up the jail. It’s ridiculous. That shit has got to stop….

You’ve got to look at the big picture. If you put quotas—which is a bad word—[officers] are going to start bum rapping people. The guy we got with the one pill, the one stop out of 10, what did I do with those other nine people that weren’t doing nothing? I stopped them. I harassed them. I asked them if they had guns in their car. I asked them if they had any illegal contraband. I’m asking them to search their car. What am I doing to the general citizen?[96]

|

Federal Funding, an Opportunity for Leadership In recent years, many advocates have expressed concern that high arrest numbers were incentivized by federal grant monies to state and local law enforcement through the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) program, administered by the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA).[97] Although funding is allocated based on a non-discretionary formula,[98] grant recipients must report back to BJA on how they use the funds, including—historically—reporting as a “performance measure” the number of individuals arrested.[99] Many groups were concerned that this sent a message to state and local law enforcement agencies that high arrests numbers meant more federal funds, and that it in turn incentivized drug arrests.[100] Recognizing that arrest numbers are not meaningful measures of law enforcement performance, BJA undertook a thorough revision of JAG performance measures, now called “accountability measures.”[101] As of fiscal year 2015, law enforcement agencies receiving JAG funds no longer must report on arrest numbers as a measure of performance or as accountability for funds received. BJA Director Denise O’Donnell told us, “Arrests can easily misrepresent what is really going on in criminal justice practice, and be misleading as to what we are really interested in seeing supported with JAG funds, namely evidence-based practices. So BJA has moved away from arrests as a metric, instead focusing on evidence-based practices, such as community collaboration, prevention, and problem-solving activities.”[102] This move is commendable. In the extensive training and technical assistance BJA provides to state law enforcement agencies, through JAG and other funding streams, BJA should reiterate that arrest numbers are not a sound measure of police performance. BJA should also encourage state agencies to pass the message along to local law enforcement agencies, which must still apply to the state agency for their share of the federal fund allocations. In many cases, that process continues to be discretionary and application-based and, in at least one recent call for applications, may still improperly emphasize drug arrests.[103] |

IV. The Experience of Being Policed

They disrupt, disrupt, disrupt our lives…. From the time the cuffs are put on you, from the time you’re confronted, you feel subhuman. You’re treated like garbage, talked to unprofessionally. Just the arrest is aggressive to subdue you as a person, to break you as a man.[104]

—Cameron Barnes, arrested repeatedly for drug possession by New York City police from the 1980s until 2012

The sheer magnitude of drug possession arrests means that they are a defining feature of the way people experience police in the United States. For people we interviewed, drug laws shaped their interactions with and views of the police and contributed to a breakdown of trust.

Instead of experiencing police as protectors, arrestees in all four states we visited described experiences in which police officers intimidated and humiliated them. They described having their pockets searched, their cars ransacked, being subjected to drug-sniffing dogs, and being overwhelmed by several officers at once. This led some people to feel under attack and “out of a movie.”[105] Prosecutor Melba Pearson in the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s office said, “The way we treat citizens when we encounter them is wrong. If they expect to have their rights violated, of course there’s going to be hatred of the police…. You can’t take an invading-a-foreign-country mentality into the neighborhood.”[106]

Pretextual Stops and Searches without Consent

Many people we interviewed said police used pretextual reasons to stop and search them, told them to take things out of their pockets, otherwise threatened or intimidated them to obtain “consent” to search, and sometimes physically manhandled them. These stories are consistent with analyses by the American Civil Liberties Union and other groups that have extensively documented the failures of police in many jurisdictions to follow legal requirements for stops and searches.

US Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor has argued in dissent that the Court’s interpretation of US law “allow[s] an officer to stop you for whatever reason he wants—so long as he can point to a pretextual justification after the fact…. When we condone officers’ use of these devices without adequate cause, we give them reason to target pedestrians in an arbitrary manner.”[107]

These fears certainly accord with the realities facing many heavily policed communities.[108] Defendants and attorneys we interviewed described a litany of explanations offered by the police to justify stopping a person on the street or in a car, many of which appeared to them to be pretextual: failure to signal, driving in the left lane on an interstate, driving with a license plate improperly illuminated or with a window tint that is too dark, walking in the opposite direction of traffic, failing to cross the street at the crosswalk or a right angle, or walking in the street when a sidewalk is provided.[109] In many jurisdictions, these reasons are not sufficient in themselves to allow the officer to search the person or vehicle.[110] Yet in police reports we reviewed for several cases in Texas and Florida, officers stopped the defendant for a traffic violation, did not arrest for that violation, but conducted a search anyway. They cited as justification that they smelled marijuana, that consent to search was provided, or that the person voluntarily produced drugs from their pockets for the officer to seize.[111] These justifications often stand in stark contradiction to the accounts of the people who were searched.

|