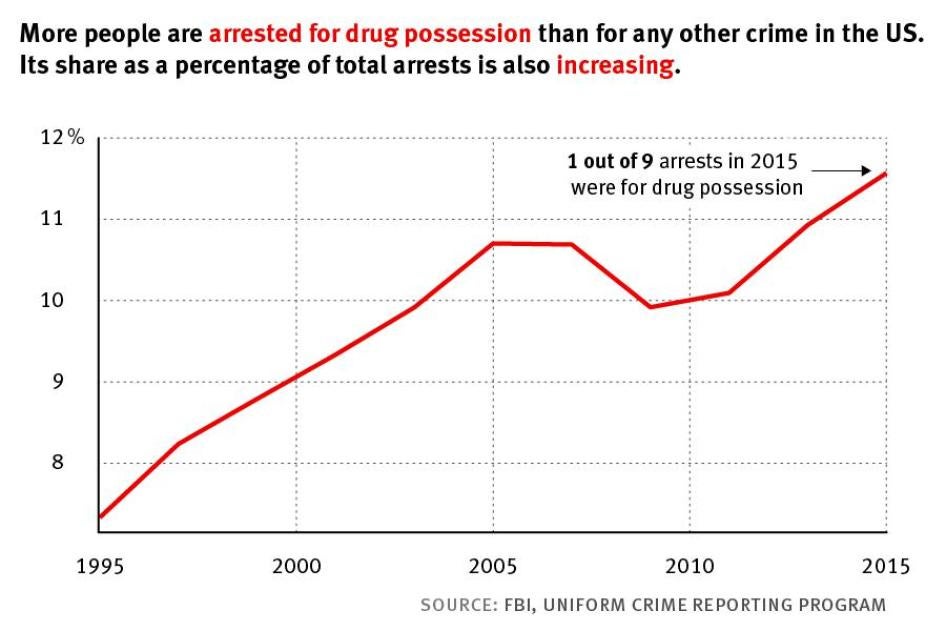

Former President Richard Nixon declared a “War on Drugs” 40 years ago. In the intervening years, the US has used its criminal justice system to dramatically crack down not only on those involved in selling drugs, but on the people who use them. As a result, today police departments across the country make massive numbers of arrests—1.25 million in 2015 alone—solely for the crime of possessing drugs for personal use. Every year, hundreds of thousands of people cycle through jails and prisons because they have used drugs, and go on to carry the stigma and the serious consequences of a criminal record. Meanwhile, drug use rates have not declined, and tragically, overdose rates have quadrupled since 1999. Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union agree: When it comes to drug use, the US criminal justice system is too broken to fix. Aryeh Neier Fellow Tess Borden talks with Amy Braunschweiger about a new report on the subject, the effects of the drug war on people in the US, and why this is important in an election year.

Why did Human Rights Watch reach the conclusion that all drug use should be decriminalized?

We have been looking at the consequences of the drug war globally for some time and have repeatedly found that the harm caused by the current approach to drugs far outweighs any benefits. When it comes to criminalizing drug use, in particular, it’s fundamentally an issue of rights: for the government to arrest someone simply for using drugs when they aren’t harming others is simply not acceptable. Our view is that it’s unjustifiable on principle, and criminalization is far worse in practice than in theory. In the US, drug enforcement imposes vastly disproportionate penalties, discriminates against Black people, hurts people who are drug dependent, and undermines public health.

How does it discriminate against Black people?

The truth is, the majority of Americans report using drugs at least once in their lives. White and Black people use drugs at the same rates. But drug laws are being enforced in ways that disproportionately impact Black communities.

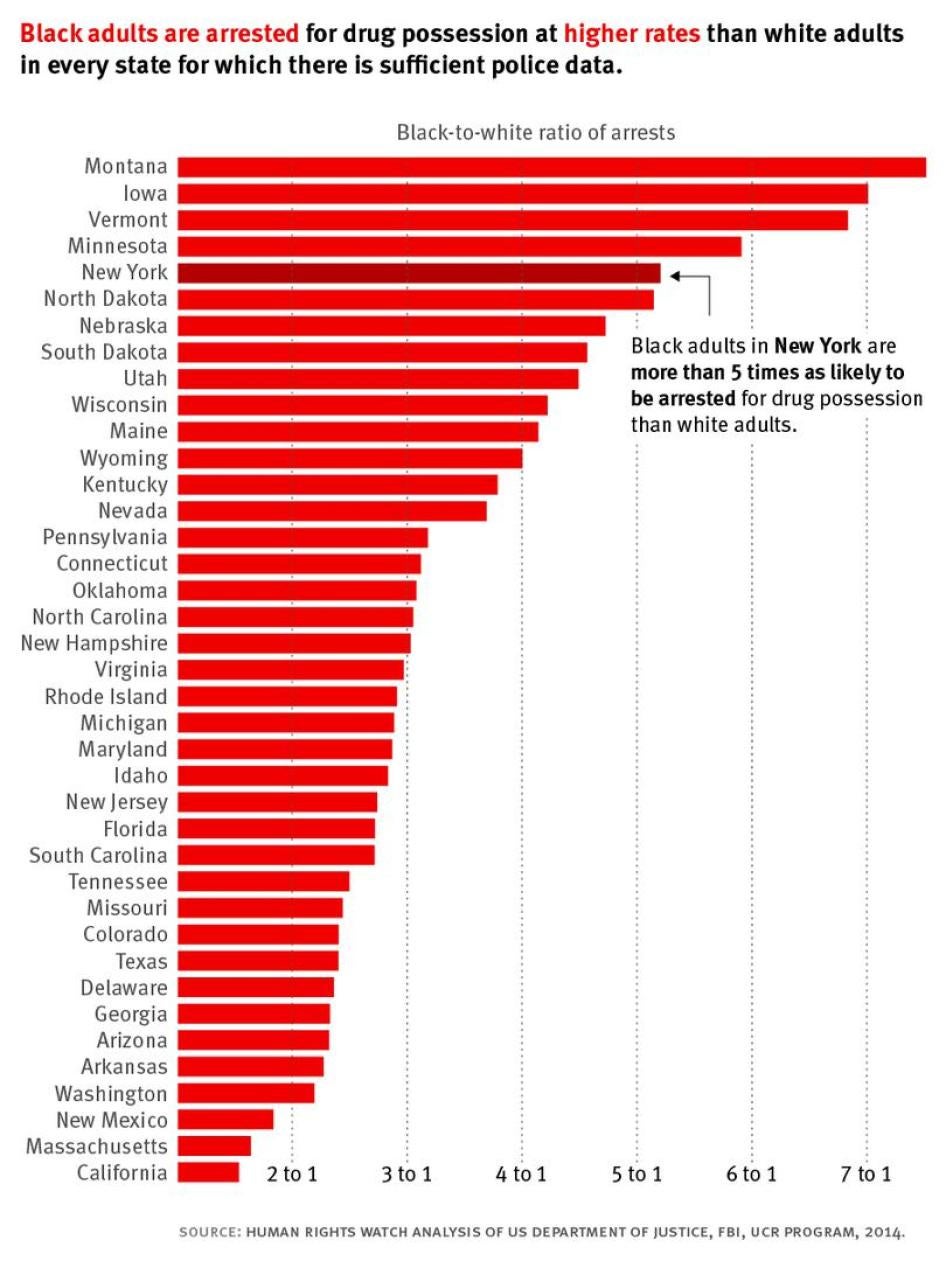

Around the country, Black adults are 2.5 times as likely to be arrested for drug possession as white adults. A Black adult is nearly four times as likely to be arrested for marijuana possession as a white adult.

How does this break down state-by-state?

In Montana, Iowa and Vermont, Black people are arrested more than 6 to 1 compared with white people. In Manhattan, the rate is 11 to 1. No state shows zero disparity.

How do Latinos and other people of color fit into this?

Data isn’t kept for Latinos. By the way, Latinos use drugs at a slightly lower rate than non-Latino Black and white people.

What’s the financial cost of this?

Arresting and locking people up costs taxpayers a lot of money.

But the real cost is for the people arrested. If you have a felony drug record, three states take away your right to vote permanently, and many more have temporary bans. According to reporting by the Tampa Bay Times, 23 percent of voting-age Black Floridians can’t vote because of felonies – many likely related to drug possession. With a drug conviction, you may also be banned from getting food stamps, cash assistance, public housing. You may not be able to serve on a jury, and may have trouble getting a job. Friends and family members may look at you differently; many people told me they felt stigmatized. And if you’re an immigrant you can be deported, separated from your US family.

What role does policing play in this?

The disproportionate arrests of Black people for drug possession means that drug possession laws are a major part of the way police interact with Black communities.

Part of it may be that drug possession arrests are relatively easier to make than arrests for violent crimes. It can’t be that all police really think people who use drugs are the number 1 public safety concern, and yet drug possession is the number 1 arrested crime.

We’re calling for the decriminalization of all personal drug use, but there is a lot that police, prosecutors, and judges can do until then. They can exercise their discretion not to arrest and prosecute certain drug possession cases, or to offer lesser charges or sentences where appropriate. They can also be more compassionate and recognize that, for people whose drug use is a problem, jail offers no solution. We want to see incentives for police to take people to treatment if they want and need it, or connect them with other services.

The stats that you quoted were striking, but what really surprised you when you set out to research this?

This report is based on more than 365 interviews, 149 of people prosecuted for drug use in New York, Florida, Louisiana or Texas. And what really struck me was, when people were arrested, how small the quantities of drugs were. I met people who were prosecuted for 0.02 or even 0.007 grams of drugs. We found that in Texas almost 80 percent of people sentenced to time behind bars for felony drug possession were convicted of possession of drugs other than marijuana that weighed less than 1 gram. That’s just a handful of doses of many drugs—and for the people I met, it was sometimes even less than a dose because they were convicted—of a felony—for possessing a hundredth or even thousandth of a gram.

Take “Matthew,” as I’ll call him, who had so little meth that the lab couldn’t even weigh it. The lab result simply read “trace.” Unlike 97 percent of people charged with drug possession in Texas, he took his case to trial. He lost and got 15 years because he had prior convictions also related to drug dependence.

“Nicole” was detained in Houston for 0.01 grams of heroin residue in a plastic baggie and coke residue inside a straw. The prosecutor could have charged her with misdemeanors, but instead charged her with two felonies. She was a young mother with three kids at home. She sat in jail for three months and missed her children so much that she finally pled guilty to heroin possession so she could go home to them that year.

She said the consequences of this felony charge would be devastating. She was pursuing a degree in business administration, but now wouldn’t get financial aid. She was relying on food stamps to feed her kids, but now wouldn’t qualify for a while. It would be challenging to get a job. And she was upset she would no longer be able to rent in her own name, because landlords typically won’t rent to “felons.” She said she felt she’d be punished for the rest of her life.

But if she’s drug dependent, couldn’t the time in jail help her quit drugs?

Most people who use drugs don’t become dependent on them. But for people who really are drug dependent and want treatment, locking them up isn’t helping them.

Most jails and prisons don’t provide themedical treatment required to overcome drug dependence. Also, people who are dependent on drugs may need social services, to help them address other problems in their lives, which are largely unavailable to them outside.

But even if people did get drug dependence treatment inside, they shouldn’t have to be locked up to get treatment. Instead of arresting people for possession, the US should make voluntary treatment programs affordable and available in the community.

This interview has been edited and condensed.