Summary

Why don’t we do routine HIV testing? We cannot afford to treat someone who was identified as HIV-positive. It sounds cold, I know, but that is the reality.

–S. Wright, nursing director, Caddo Parish Correctional Center, Shreveport, Louisiana,April 8, 2015

Of all the life events that knock people out of HIV care, going to jail is one of the biggest disruptors.

—Dr. Anne Spaulding, associate professor at Emory University and a national expert on HIV in corrections

In 2011, the United States, in concert with countries around the world, announced the “beginning of the end of AIDS.” Defeating AIDS would be a stunning achievement in public health. But doing so requires effectively diagnosing, treating, and maintaining individuals with HIV while they receive care.

In the United States, this inevitably means addressing HIV in correctional settings. That is because the populations at risk of HIV and the populations that are incarcerated—including people who use drugs, sex workers, the poor, the homeless, and racial and ethnic minorities—overlap in the US. The prevalence of HIV among incarcerated persons is three times greater than in the general population. One out of seven people living with HIV will enter a jail or prison each year.

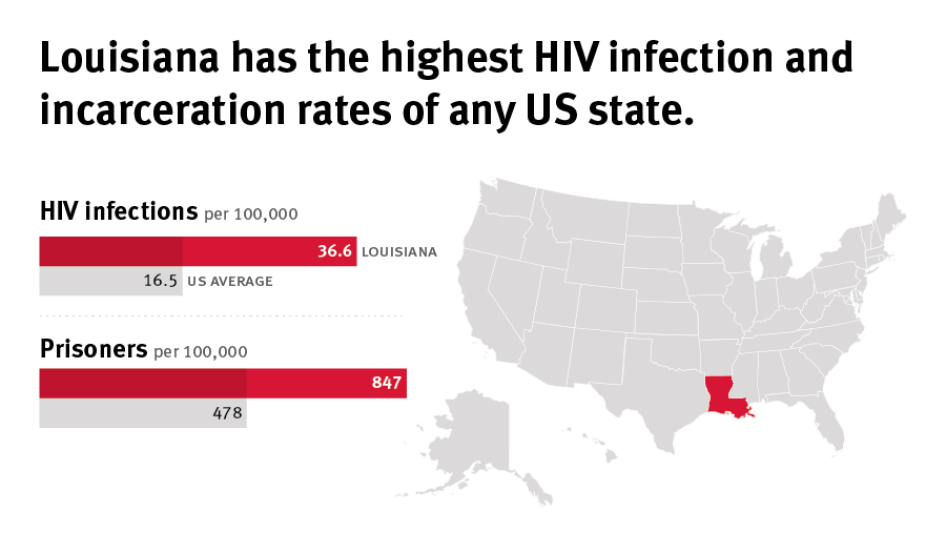

Nowhere is the need for reform more urgent than in Louisiana, which incarcerates people at a higher rate than any other US state. At any given point in time, roughly 1 in 75 Louisiana adults are in jail or prison.

In Louisiana parish jails, thousands of people charged with minor, non-violent crimes endure lengthy pre-trial detention, and those with HIV often go undiagnosed, untreated, and without effective community care upon release. Many Louisiana AIDS service providers estimate that between one-quarter to one-half of their clients have been in jail or prison—in many cases frequently—an experience that endangers their health, safety, and even their lives.

Based on interviews with around 100 individuals—including representatives of organizations involved in HIV and health services and related to the criminal justice system—this report presents the voices of people living with HIV who have been incarcerated in parish jails across Louisiana, where HIV services are limited, haphazard, and in many cases, non-existent. It examines HIV testing programs in local jails in Louisiana, finding that only a handful conduct routine, voluntary testing programs as recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control. The report documents HIV treatment in jails that is delayed, interrupted, and in some cases denied altogether. Despite the importance of continuity of care to people living with HIV, most inmates leaving jails in Louisiana receive little help in finding, or returning to, a community care provider.

The state of Louisiana is “ground zero” for the dual epidemics of HIV and incarceration. Its two major cities, Baton Rouge and New Orleans, lead the country in new HIV infections each year. The death rate from AIDS in Louisiana is among the highest in the US. As of January 2016, the Louisiana Department of Corrections housed 525 prisoners living with HIV; in 2010, the prevalence of HIV in Louisiana state prisons was 3.5 percent, the second highest in the country.

The United States’ incarceration rate is the highest reported in the world, and Louisiana incarcerates its residents at a rate 150 percent higher than the national average, higher than any other state. Louisiana parish jails hold more than 30,000 people daily, including people convicted of relatively minor offenses by local courts, some federal prisoners, and nearly half of the state prison population.

The same socioeconomic factors that place people at risk for HIV—poverty, homelessness, drug dependence, mental illness—also place them at higher risk of incarceration. The HIV epidemic and the criminal justice system are marked by similarly disturbing racial disparities: in Louisiana, African-Americans are 10 times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV and five times more likely to be incarcerated than whites.

For heavily policed groups, such as people who use drugs, sex workers, transgender women, and LGBT youth, the overlap of HIV and imprisonment is not a coincidence. Going to jail tends to make people poorer, less stably housed, and more likely to be jailed again—all factors known to play a part in HIV prevention and outcomes. Even brief incarcerations are likely to interfere with people’s access to, or use of, HIV medications and reduce the chances of achieving viral suppression, the pinnacle of good health for someone living with HIV.

Inadequate Treatment in Parish Jails

Many HIV positive people, including prisoners, do not know they are living with HIV. The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that all correctional facilities provide routine voluntary HIV testing to promote awareness of their status as well as linkage to medical care in the facility and upon release. Yet in Louisiana, only 5 of 104 parish jails regularly offer HIV tests. At other parish jails, HIV tests are conducted only if a prisoner appears ill, or in some cases if requested. In a state facing one of the country’s worst HIV epidemics, the extent of HIV in Louisiana parish jails remains unknown; when asked if they were holding any prisoners with HIV, several jail officials Human Rights Watch interviewed said that they were not aware of any.

Cost as a Barrier to Treatment

The reasons for limited testing are not a mystery. HIV medication is expensive; a treatment course can average more than $50,000 per year. In Louisiana, jail budgets are the responsibility of local parishes, the equivalent of counties in other US states. Several jail officials told Human Rights Watch that they avoided HIV testing because they could not afford to provide treatment to prisoners testing positive for HIV.

The federal government offers little assistance. With few exceptions, it does not fund HIV treatment for state or local prisoners. Federal Medicaid excludes all incarcerated persons from coverage, and services under the Ryan White Act that assist people living with HIV are of limited availability for people in jail or prison. Federal programs permitting nonprofits to purchase medications at a discount are not available to correctional facilities.

Jail health budgets are under added pressure from the state’s recent privatization of LSU “charity” hospitals that used to provide subsidized medical services to state and local prisoners. Under the new system, the state Department of Corrections (DOC) holds the purse strings for aspects of what it calls “offender care” and has decided—apparently purely due to budgetary constraints—that HIV care is not a reimbursable expense.

This leaves jails on their own, and means they have a powerful incentive not to encourage prisoners to disclose or test their HIV status. Officials at jails that do offer testing and HIV treatment said that medication costs consume large portions of their total health budgets.

In parish jails throughout Louisiana, HIV treatment is often delayed, interrupted, or denied altogether. For prisoners living with HIV, the health consequences can be devastating. Case managers at AIDS service organizations throughout the state described clients who “disappear” into jails, go months without HIV medications, emerge gravely ill, and in some cases, die after release. “I took sick.... I had flu, congestion, bumps on my skin, I lost a lot of weight,” said Keith, 32, who spent two years in a parish jail without HIV medication. “I was scared. I was going through a crisis in there.”

Most Louisiana parish jails also do not ensure that people living with HIV connect to medical care when they return to the community. In Louisiana, only half of people living with HIV remain in care after visiting a doctor, and many are lost to care after leaving a correctional facility. With few exceptions, release from parish jail is a haphazard process consisting of whatever is left of their medication package, a list of local HIV clinics, or often nothing at all.

When clients fail to appear for appointments, some HIV case managers told us that they check jail websites and, if they manage to locate them, simply hope for their eventual return, expecting no communication from the jail or the client.

Many prisoners living with HIV, fearing discrimination and harassment by guards or other inmates, choose not to disclose their HIV status while incarcerated even though it means missing doses of medication. As one case manager explained, “If they saw people being treated and linked to care, they might disclose, but right now there is only the downside.”

State Prisoners in Parish Jails

The state Department of Corrections (DOC) operates an HIV testing program and a strong discharge planning program for HIV-positive prisoners housed in its nine state facilities. But in Louisiana, roughly half of all state prisoners—about 18,000 people as of early 2016— are housed not in DOC facilities but in parish jails. DOC offers no testing, treatment or discharge planning services to any of these prisoners—essentially running a two-tiered system that ignores the potential need for HIV services among nearly half of its population.

The DOC tries to justify this approach by claiming that no HIV-positive prisoners are in local parish jails, and maintains that HIV-positive prisoners are promptly transferred to DOC facilities, an approach that ignores the lack of routine HIV testing in parish jails. Even for inmates who disclosed their status in a parish jail, Human Rights Watch received several reports of HIV-positive DOC prisoners who were not transferred out of parish jails and did not receive adequate treatment for HIV in the parish facility. By claiming there are no HIV-positive prisoners in parish jails, DOC avoids responsibility for providing equivalent HIV testing, treatment, and linkage to care for this highly vulnerable population of DOC prisoners.

Human Rights Obligations

Louisiana’s failure to ensure that prisoners have HIV testing, treatment, and linkage to care upon release is inconsistent with its obligations under international human rights law.

- To protect the right to the highest attainable standard of health and provide adequate medical care in detention, the state of Louisiana, parish governments, and the federal government should ensure that policies promote and ensure access to HIV care in all state and local correctional facilities.

- Louisiana Department of Corrections should address undiagnosed HIV in parish jails and end funding exclusions for HIV-related services for prisoners in parish jails.

- Louisiana should ensure that prison health services have enough funds to meet international legal obligations to a population that depends on it for health care.

- Louisiana health officials should ensure that all detention facilities have strong HIV testing programs in place, and facilitate participation in federal programs that will help pay for HIV medications for prisoners awaiting trial.

- Policymakers should consider that when it comes to people living with HIV, public health objectives may best be met by avoiding detention altogether. For prisoners living with HIV who stay in jail without adequate treatment, health consequences become more serious the longer treatment is delayed, interrupted, or denied, and treatment becomes more expensive.

Louisiana has taken some important steps, including reducing mandatory minimum sentences, revising marijuana laws, and expanding parole and probation opportunities. In New Orleans, innovative projects have significantly cut its jail population, and risk assessment tools help judges identify and release pre-trial defendants who pose no risk to the community. Alternatives to arrest, incarceration, and pre-trial detention should be urgently explored and expanded, state-wide.

There is no time to waste. Detention in Louisiana parish jails endangers the health, safety, and the very lives of people living with HIV.

Recommendations

To the Louisiana State Government

- Establish an independent body for monitoring conditions in parish jails with responsibility to report to the governor, the legislature, and to the public.

- Ensure adequate funding for medical services in parish jails, including routine voluntary rapid HIV testing, treatment, and linkage to care for pre-trial, sentenced, and DOC detainees.

- Extend the requirement for routine voluntary HIV testing in the Department of Corrections facilities to parish jails, preferably upon entry.

- Support the Greater New Orleans Health Information Exchange (GNOHIE) initiative and expand initiatives throughout the state to increase the connectivity of medical records between parish jails and local primary care providers, hospitals, and other health service providers.

- Increase access to mental health services and community-based voluntary treatment centers to reduce risk of arrest and incarceration of people with mental health conditions.

- Support and expand criminal justice reform initiatives to reduce arrest and incarceration rates including bail and sentencing reform, implementation of evidence-based pre-trial procedures and risk assessments, decriminalization of drug possession and use, and ensure adequate funding for courts, prosecutors, and public defenders.

To the Louisiana Department of Corrections

- In the short term, implement an effective, comprehensive effort to identify all DOC prisoners in parish jails that are HIV-positive through voluntary testing with informed consent and offer voluntary transfer to a DOC facility for those testing positive.

- In the long term, ensure access to routine voluntary HIV testing, treatment, and linkage to care for DOC prisoners in parish jails that is equivalent to those available in DOC facilities.

- Include HIV as specialty care eligible for coverage by DOC’s medical budget.

- Improve monitoring of medical care in parish jails holding DOC prisoners to ensure access to HIV treatment and care.

To the Louisiana Sheriff’s Association and Local Parish Jails

- Implement routine, voluntary HIV testing at entry and/or release.

- Ensure adequate HIV treatment for all HIV-positive inmates.

- Ensure linkage to care in the community for all HIV-positive inmates.

To the Louisiana State Office of Public Health

- Provide support, education, and training for increased access to routine voluntary HIV testing, treatment, and linkage to care in Louisiana parish jails, including by:

- Training staff of AIDS service organizations to clarify federal eligibility requirements for HIV treatment and case management services for clients incarcerated in Louisiana parish jails;

- Training medical staff from parish jails and local AIDS service organizations to maximize strategies and procedures to improve testing, treatment, and linkage to care;

- Establishing pilot programs for utilization of ADAP program funding for HIV treatment for pre-trial detainees in Louisiana parish jails;

- Supporting the New Orleans GNOHIE initiative and expanding initiatives throughout the state to increase the connectivity of medical records between parish jails and local primary care providers, hospitals, and other health service providers;

- Establishing a statewide health liaison program to promote alternatives to incarceration for people living with HIV and other chronic conditions.

To the United States Government

- Congress and implementing regulatory agencies should review the impact of restrictions on eligibility for HIV treatment, case management services, and linkage to care for incarcerated persons, particularly those in local jails, in federal legislation including the Medicaid provisions of the Social Security Act, Ryan White CARE Act, the Affordable Care Act and the Public Health Services Act, section 340b. Such restrictions should be removed or revised to increase access of persons incarcerated in local jails to HIV treatment, case management services, and linkage to care.

- The Office of National HIV/AIDS Policy should convene and support an inter-agency task force to examine the role of the criminal justice system, including arrest, incarceration, and re-entry, in the domestic HIV/AIDS epidemic. The task force should be empowered to make recommendations for reform at the federal, state, and local levels.

The Department of Justice should follow the recommendations set forth by the American Bar Association’s “Key Requirements for the Effective Monitoring of Correctional and Detention Facilities” to support increased independent oversight and transparency of state and local correctional facilities, including the provision of technical assistance for such oversight and the conditioning of federal correctional funding on adequate oversight procedures and transparency.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in Louisiana between October 2014 and December 2015.

Human Rights Watch interviewed approximately 100 individuals and representatives of organizations involved in HIV and health services, including the state office of public health, and related to the criminal justice system, including judges, prosecutors, public defenders, and employees of Louisiana parish jails.

Human Rights Watch visited AIDS service organizations in each of the nine public health regions of the state, interviewing directors, case managers, and staff who frequently interact with jail-involved clients.

These organizations facilitated in-person or telephone interviews with 27 individuals living with HIV who had been incarcerated in a Louisiana parish jail in the last two years. All persons interviewed were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the information would be used. Interviewees received minimal travel reimbursement but no financial compensation for participating in interviews. All interviewees provided oral consent to be interviewed.

Pseudonyms are used for all formerly incarcerated persons in order to protect their privacy, confidentiality, and safety.

Human Rights Watch met on numerous occasions with the staff of the state HIV/STD prevention office, the federal AIDS Education Training Center, and Ryan White program administrators in Baton Rouge and other major cities. Interviewees also included the medical director of the state Department of Corrections, the staff of the Special Projects of National Significance (SPNS) programs providing linkage to care for Louisiana prisoners, and medical staff of 40 parish jails in geographically diverse locations, both public and privately operated, and representing each of the nine public health regions in the state.

Repeated requests between May 2015 and January 2016 for in-person and/or telephone interviews with the Louisiana Sheriffs Association were never granted.

Human Rights Watch interviewed participants in all aspects of the criminal justice system, including judges, prosecutors, public defenders, police officers, city attorneys, the Vera Institute of Justice, Roderick and Solange MacArthur Justice Center, the Promise of Justice Initiative, director of the ACLU of Louisiana and directors and staff of prison re-entry organizations.

Human Rights Watch conducted legal and policy research as well as interviewing state legislators, staff of the state Legislative Fiscal Office, city council and parish commission members, legal and policy advocates, and academics. Documents were obtained and shared with Human Rights Watch from multiple sources, including the state Legislative Fiscal Office, the Lafayette, Orleans, Jefferson and East Baton Rouge Parish jails, the Caddo Parish Commission, public defenders and prosecutors, the Louisiana Public Health Institute, the Vera Institute of Justice, and the state Office of Public Health. All documents cited in the report are publicly available or on file with Human Rights Watch.

I. Background

HIV in the United States

More than 1.2 million people in the United States are living with HIV, and one in eight are unaware of their infection.[1] Over the past decade, the number of people living with HIV has increased as treatment has become more effective, while the number of new infections has remained relatively stable overall.

However, rates of infection are high among certain groups, identified by the Office of National HIV/AIDS Policy as “priority populations.”[2] These have been identified as gay, bisexual or other men who have sex with men; African-American men and women; Latino men and women; people who inject drugs; youth 13-24 years old; people in the southern United States; and transgender women.[3]

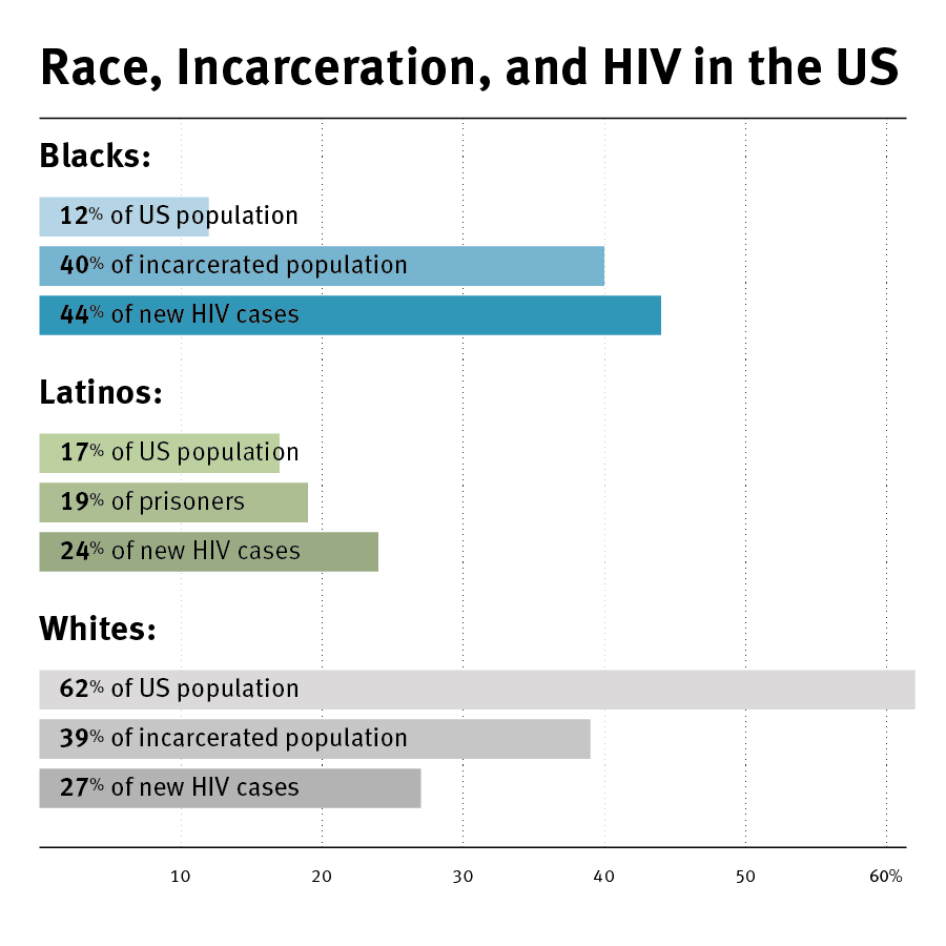

Racial disparities are stark, with blacks comprising 12 percent of the US population but 44 percent of new HIV infections. The rate of HIV infection among African-Americans is eight times higher than among whites, with black men seven times and black women twenty times more likely than whites to become infected.[4] Latinos are also disproportionately affected by HIV, comprising 17 percent of the US population but nearly a quarter of new HIV infections.[5]

In recent years, treatment has become the cornerstone of both HIV prevention and care. Public health and HIV experts have increasingly emphasized the importance of early and universal access to anti-retroviral medication not only to improve individual outcomes but to reduce the risk of transmission of the virus to others.

The approach characterized as “Treatment as Prevention” has gained traction both in the US and globally as studies indicate that sufficient suppression of the virus through anti-retroviral therapy can dramatically reduce the possibility of transmission from one person to another and in communities as a whole.[6] Anti-retroviral medications are also being offered to those at high risk of becoming HIV-positive, as pre-exposure prophylaxis, or “PrEP” therapies become available globally and in the US.[7]

Key to the success of this approach is the ability of the person to become aware of their status and sustain a lifetime course of anti-retroviral medication that must be taken on a daily basis. Continuity is particularly important with anti-retroviral drugs as adherence has been strongly associated with suppressing the virus, increased life expectancy, and avoiding resistance to HIV medications. When resistance is developed to medication, treatment becomes more complex and alternative medications are often more expensive. According to the US Centers for Disease Control: “The prevention benefit of treatment can only be realized with effective treatment, which requires linkage to and retention in care, and adherence to anti-retroviral therapy.”[8]

Nationally, most people living with HIV (87 percent) have been diagnosed, and 81 percent have been “linked to care” by attending an initial medical visit. Staying in care, however, is highly problematic; only 39 percent of people linked to health services remain in care, and of those, only one in three achieves the goal of viral suppression.[9] Racial and ethnic minorities have poorer outcomes than whites at every stage of the continuum of care.[10]

The updated US National HIV/AIDS Strategy identifies increased retention in HIV care as a high priority, setting the ambitious goal of doubling the percentage of people who stay in care.[11] Yet the role of the criminal justice system in pushing people out of the care continuum goes largely unaddressed in the national strategy, despite increasing evidence that chronic cycles of arrest and incarceration impact those at greatest risk of HIV and impede their ability to sustain an effective course of HIV treatment.

HIV and Incarceration

In 2014, 1.5 million people were incarcerated in US state and federal prisons, with an additional 700,000 detained in local jails.[12]The same socioeconomic factors that make people vulnerable to HIV—poverty, homelessness, mental illness, and substance use—also place them at higher risk of incarceration.[13]

The prevalence of HIV among incarcerated persons is three times greater than in the general population, and one out of every seven people living with HIV will enter a jail or prison each year.[14] People who use drugs and those who exchange sex for money, drugs, or life necessities face the dual risk of HIV and criminalization; globally, between 56 and 90 percent of people who inject drugs will be incarcerated at some point in their lives.[15] LGBT people, particularly gay men, transgender women, and youth, are all over-represented in both the HIV epidemic and in the US criminal justice system.[16] Many countries, and 33 states, including Louisiana, impose criminal penalties on persons who know their HIV status and allegedly expose another person to HIV. [17] International and US health authorities have criticized these laws as unnecessary, stigmatizing, and counter-productive to public health objectives. [18]

Race, HIV, and Incarceration

In the US, both the HIV epidemic and incarceration are marked by significant racial disparities. Blacks and Latinos are 12 and 17 percent of the US population but comprise 44 and 24 percent, respectively, of new HIV diagnoses.[19]

African-Americans and Latinos are one quarter of the US population but 58 percent of prisoners in the US.[20] Black men are seven times, and black women three times, more likely to be incarcerated than their white counterparts.[21] One in three black men can expect to be incarcerated in his lifetime, compared to one in seventeen white men.[22]

African-American transgender women exemplify the disturbing overlap of HIV and incarceration burden in heavily policed populations.[23] HIV prevalence among African-American transgender women has been found to be as high as 30 percent in some studies; at the same time, half of all black transgender women in the US report a history of incarceration.[24]

Over the past decade public health experts have increasingly recognized that a substantial number of individuals with, or at risk of, HIV regularly interact with the criminal justice system. Internationally, WHO and UNAIDS have developed guidelines for HIV testing, treatment and linkage to care upon release for incarcerated persons.[25] Moreover, UNAIDS has stated that the criminalization of sex work, drug use, and same-sex relationships among consenting adults hinders delivery of effective HIV interventions, and has called for laws criminalizing same sex relations to be overturned and for sex work and drug use to be decriminalized.[26] According to research in The Lancet, decriminalizing sex work could avert 33 to 46 percent of new HIV infections among sex workers and their clients in the next decade.[27]

In the US, people in jail or prison are likely to be poor, with incomes averaging 41 percent lower than the general population.[28] Significant numbers of people entering the criminal justice system lack health insurance and have poor access to primary health care. Many people first receive an HIV diagnosis and anti-retroviral therapy (ART) while in jail or prison.[29]

Testing

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) have identified correctional facilities as key sites for HIV intervention, recommended routine voluntary HIV testing in local, state, and federal prisons, and issued technical guidance for testing, treatment, and linkage to care upon release.[30] “Routine” testing covers every inmate on entry and can be either mandatory or voluntary. Mandatory testing is not consistent with ethical or human rights principles of privacy, autonomy, and informed consent. International and domestic public health experts oppose it both in and out of a correctional context. [31]

Voluntary routine testing can be conducted under the “opt-out” model, where the inmate is informed that HIV testing will be conducted as part of initial medical examination unless the test is specifically declined. Under the “opt-in” approach, each inmate is given the opportunity to request an HIV test during the initial medical exam or shortly thereafter.

According to the CDC, the “opt-in” method can be used in correctional settings but these models “have been shown to miss diagnosing a significant number of HIV-infected persons and therefore are not the ideal.”[32] “Opt-out” approaches in correctional facilities should be carefully designed to address issues of consent, confidentiality, and safety. “Opt-out” approaches should be implemented in a manner that ensures individual autonomy and conforms to ethical principles. [33]

Pilot projects funded by the CDC and other government agencies have established that HIV prevention and treatment in correctional settings is feasible and effective (See Rikers Textbox).[34] Rapid tests return results in under one minute. Current protocol for HIV treatment calls for initiation of anti-retroviral medication as soon after diagnosis as possible. It is no longer necessary to establish a low CD-4 count or elevated viral load before starting medication, though viral load and resistance testing should be implemented to determine appropriate treatment.[35]

However, the quality of HIV services in corrections is uneven, and particularly weak in the areas of testing and post-release linkage to care. A recent national survey found that only half of responding jails did routine HIV testing, split evenly between opt-out and opt-in testing.[36] Fewer than one in five jails or prisons follow CDC recommendations for correctional discharge planning.[37] The US National HIV/AIDS strategy document, revised in 2015, makes scant mention of the criminal justice system. The strategy does, however, address the issue of linkage to care for HIV-positive prisoners:

Those who are incarcerated may have difficulty accessing HIV medications, especially those in jail or short-term detention. Strong linkages to new health homes and supportive services are needed as part of re-entry programs for persons with HIV who are being released from correctional facilities, including enrollment for disability or Medicaid prior to release and referral to substance use and mental health services and medical care.… Facilitating initial appointments post-release and comprehensive case management help ensure better health outcomes related to HIV infection and treatment for substance use disorders.[38]

Funding

Funding is a major barrier to implementing HIV interventions in jails and prisons. Testing, treatment, and linkage to care requires investing money and staff.[39] The federal government is the primary funding source for managing the HIV epidemic in all 50 states.[40]

The unavailability of this federal funding for prisoners significantly impacts the response to HIV in local correctional settings.

Medicaid, the federal government’s primary health insurance program for low income persons, excludes all incarcerated persons from coverage other than specified hospital costs.[41] The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program provides health care and essential support services including housing and case management to uninsured people living with HIV, but incarcerated persons are ineligible until 180 days prior to release.[42] Ryan White also funds the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) that supports prescription medications for persons living with HIV but ADAP excludes incarcerated persons whose case has been determined, either through conviction or a guilty plea.[43] The federal program for purchasing discounted medications for certain non-profit entities, the “340b” program, excludes correctional facilities as covered entities.[44]

There are, however, numerous ways to utilize federal assistance for HIV-positive incarcerated persons, and many states and localities are maximizing these opportunities.

HIV medications are available to persons in pre-trial detention under ADAP, and 17 states are taking advantage of this provision to deliver medications to incarcerated individuals in local jails.[45] The Affordable Care Act offers states the option of expanding their Medicaid programs to all persons whose income is below 138 percent of the federal poverty level with most of the cost assumed by the federal government until 2025.[46] Nationally, this has already significantly increased the number of people living with HIV eligible for Medicaid health insurance coverage.[47] If they went to jail or prison, their benefits would be suspended or terminated during their incarceration. However, discharge planning prior to re-entry could facilitate their enrollment in the program upon release.[48]

Since 2010, Louisiana has declined to expand its Medicaid program, but the state may be poised to change its stance after the gubernatorial election in 2015 brought Jon Bel Edwards into office. Shortly after his inauguration in January 2016, Governor Edwards announced his intention to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, and signed an executive order to that effect on January 12, 2016.[49]

The Affordable Care Act also established an exchange market for subsidized health insurance for low to middle income people, and these exchanges permit incarcerated persons who meet eligibility requirements to enroll in an insurance plan within 60 days of release.[50] In recent years, Louisiana state health officials have made an effort to enroll significant numbers of HIV-positive persons in the health insurance exchanges upon their release from incarceration.[51] In addition, Louisiana is implementing several federally funded initiatives to improve testing and linkage to HIV care upon release from state prisons, as discussed further below.

Disruption Caused by Incarceration

While correctional settings may present opportunities to identify new HIV cases, initiate treatment, and facilitate aftercare, these public health benefits are undermined by the disruption to individuals, families, and communities caused by arrest and incarceration.

Research increasingly indicates that incarceration is a marker for higher risk of HIV, reduced adherence to anti-retroviral medications, and poorer health outcomes once infected.[52] Going to jail particularly impacts an individual’s ability to adhere to HIV medications, a key element of successful management of HIV.

One study, for example, focused on injection drug users with HIV who had attained undetectable viral loads, the pinnacle of good health for individuals living with HIV. Even a brief incarceration, however, doubled their chances of returning to virologic failure.[53] As stated by Dr. Anne Spaulding, associate professor at Emory University and a national expert on HIV in corrections, “Of all the life events that knock people out of HIV care, going to jail is one of the biggest disruptors.”[54]

HIV in Louisiana

The state of Louisiana, along with the rest of the US South, lies at the center of the nation’s HIV epidemic. In 2014, Louisiana had the second highest rate of HIV infection and the third highest rate of AIDS among adults and adolescents in the United States.[55]

As of June 2015, there were 20,272 known cases of people living with HIV in Louisiana, over half of whom have been diagnosed with AIDS.[56] Many are diagnosed in late stages of illness, and one in threediagnosed with HIV are not receiving HIV-related medical care.[57] Late diagnosis and lack of medical care contribute to a death rate from AIDS that is more than double the national average and the 6th highest in the nation.[58]

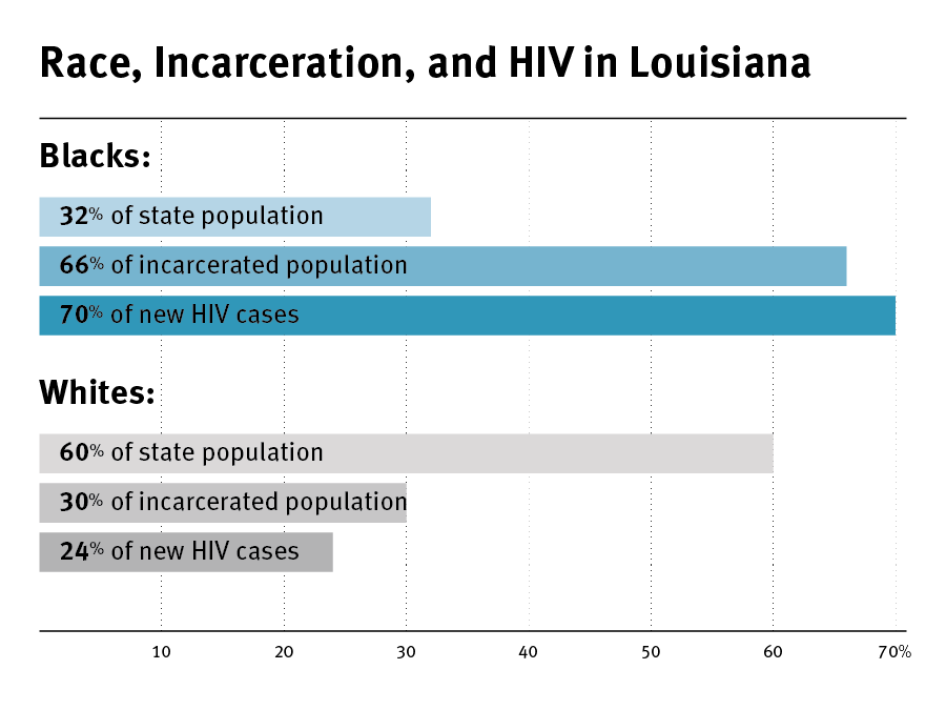

Racial disparities are dramatic in the state’s HIV epidemic. African-Americans are 32 percent of the state population, but they comprise 70 percent of newly diagnosed HIV cases and 74 percent of new AIDS cases.[59] Overall, African-Americans are 10 times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV than whites in Louisiana.[60] The rate of newly diagnosed HIV cases among African-American women is 16 times higher than the rate among white women.[61]

Male-to-male sexual contact is the predominant mode of transmission for both those living with HIV and newly diagnosed infections, followed by “high-risk heterosexual contact” and injection drug use. Among women, the primary modes of transmission are high-risk heterosexual contact and injection drug use.[62]

Most people living with HIV in Louisiana live in the state’s two largest cities, Baton Rouge and New Orleans. In these metropolitan areas, the epidemic continues to spread at rates that lead the nation. In 2013, an eight-parish region, known to the CDC as the New Orleans Eligible Metropolitan Area (NOEMA) for HIV surveillance and data purposes, had the second-highest rate of new HIV infections in the United States and the fifth-highest rate of AIDS cases in the US.[63]

The Baton Rouge Transitional Grant Area (BRTGA) includes nine parishes, and in 2013 ranked fourth in the nation for new HIV infections and third for new AIDS diagnoses.[64] New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Shreveport together accounted for 66 percent of the state’s new HIV diagnoses in 2012.[65]

Poverty is a primary driver of the HIV epidemic in the United States, and Louisiana’s poverty levels are among the highest in the nation.[66] In 2013, 19 percent of the state’s residents lived below the US federal government’s poverty line ($24,450 for a family of 4 in 2015) compared to 15 percent nationwide, and racial and ethnic minorities are significantly more likely to be poor. [67] In Louisiana, 34 percent of blacks and 39 percent of Hispanics live below the federal poverty line compared to 10 percent of whites.[68]

Medical Care

In a state with one of the highest rates of uninsured persons in the country, Louisiana has chosen for decades to take a “safety net” rather than an insurance coverage approach to medical care for the poor, which favors emergency over primary or preventive care.

Louisiana’s Medicaid eligibility is extremely restrictive, requiring parents of dependent children to earn less than 24 percent of the federal poverty level in order to qualify ($5,820 annual income for a family of four)—lower than all but three US states. It also does not offer any coverage to childless adults.[69] The state’s decision not to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act has prevented more than 200,000 people in Louisiana from obtaining health insurance coverage, including some 4,000 people living with HIV.[70]

Prior to 2012, Louisiana State University (LSU) hospitals acted as the state’s primary “safety net” for poor and insured residents, serving more than 500,000 patients a year for no charge or at subsidized rates. Most encounters at the LSU hospitals were in the emergency room rather than in primary care clinics, and the system received poor grades from independent health authorities for lack of comprehensive or preventative services and avoidable hospitalizations.[71]

However, the “charity hospital” era in Louisiana ended in 2012. That year the state faced an $860 million budget gap following a reduction in federal Medicaid payments due to a previous overpayment to the state.[72] The administration of Governor Bobby Jindal responded by slashing health care budgets state-wide, including those of the LSU hospitals, Medicaid, and mental health services—including behavioral health and childhood development programs, and community mental health centers. [73]

Governor Jindal then announced a reorganization of hospital care in Louisiana designed to “modernize” the health care system.[74] By the end of 2012, three of the nine LSU hospitals had agreed to partially privatize by contracting with private health care companies, and by mid-2013 eight new “public-private” hospital partnerships had been announced, with only one LSU hospital remaining under public ownership.[75]

The state of Louisiana relies heavily on the federal government to fund its management of the HIV epidemic.[76] More than half of the people known to be living with HIV in Louisiana, an estimated 11,000 clients, rely on care and support services provided under the federal Ryan White CARE Act.[77] Prior to hospital privatization, each LSU hospital had a specialized HIV/Infectious Disease Clinic funded through Ryan White, and in New Orleans and Baton Rouge Ryan White funding supported AIDS service organizations to operate HIV clinical programs as well. Although some of the new hospital entities discontinued their HIV clinics, Ryan White funded services have continued.[78]

The new hospital entities have also continued to participate in the Louisiana Public Health Information Exchange Program (LAPHIE) under which hospitals, primary care providers and the state Office of Public Health share information to identify people who are not receiving HIV treatment, a program that has improved continuity of care significantly since 2009.[79]

However, significant unmet need remains in Louisiana. Overall, one in three people living with HIV are not in care. Of those diagnosed with HIV, 79 percent see a doctor within 90 days, but half of them will drop out of care.[80]

Incarceration in Louisiana

The US incarcerates its citizens at a higher rate than any other nation, and Louisiana’s incarceration rate is 150 percent higher than the national average.[81] At any given point in time, roughly 1 in 75 Louisiana adults are in jail or prison.[82]

As of December 2015, approximately 36,400 prisoners were in the state system operated by the Louisiana Department of Corrections. Of these, roughly half were held in in state custody in nine state facilities (including two that are privately operated). The remainder were held in local parish jails (roughly 15,000) and work release centers (3,000).[83] In addition to the state prisoners, 104 parish jails also held approximately 12,600 pre-trial detainees and another 2,200 people serving sentences on local charges.[84]

Racial disparities in incarceration are dramatic in Louisiana, with African-Americans incarcerated at a rate five times higher than whites.[85] African-Americans comprise 32 percent of the state population but 66 percent of people in jail or prison.[86] Louisiana’s drug laws are among the toughest in the nation; in 2013, more than 20,000 people were arrested in Louisiana on drug-related charges, half of whom were African-American.[87]

The housing of nearly 50 percent of Louisiana’s state prison population in local parish jails is unique; nationally, only 5 percent of prisoners serving state sentences are housed in locally operated facilities.[88] This arrangement stems from a lawsuit filed in the 1970s challenging overcrowding and other conditions in state-operated prisons that was settled by court orders requiring the state to relieve severe overcrowding in those facilities.[89] In an effort to satisfy this obligation, the legislature authorized the transfer of state-sentenced prisoners to the custody of parish jails operated by local sheriffs.

There is no formal guideline for determining assignment to state prison or a parish jail. Each individual is assessed for housing on a case by case basis, and according to state prison officials, generally state prisoners in parish jails are younger, charged with less serious or non-violent offenses, and have no severe medical or mental health issues.[90]

To facilitate the transfer of state prisoners to parish jails, the state established a daily reimbursement for each parish-held prisoner.[91] This reimbursement rate, currently $24.39 per day, provides financial incentives for local sheriffs to house state inmates. The system has been criticized as also incentivizing local sheriffs to build large jails even in small counties, and to oppose criminal justice reforms that could reduce prison populations.[92] One official with the state legislative fiscal office told Human Rights Watch, “Any time they propose reduced sentencing the sheriffs oppose it because they keep the jails full.”[93]

Several other factors contribute to Louisiana’s high rates of incarceration. In 2012, the Louisiana Sentencing Commission found that mandatory minimum sentencing for drug and other non-violent offenses accounted for more than 60 percent of admissions; that 42 percent of parole and probation violations that returned people to prison were for technicalities; and that parole grants had dropped almost 60 percent in the last decade.[94]

In Louisiana, as across the country, imposition of unreasonable bail keeps many defendants in jail pre-trial because they cannot come up with the money.[95] In addition, the ACLU of Louisiana has alleged that widespread incarceration for nonpayment of fines, fees, and other costs defendants are genuinely unable to afford has given rise to a “pay or stay” system that violates poor offenders’ rights.[96]

In Louisiana, bail is defined as the security provided by a defendant to ensure his appearance in court when required.[97] A commercial bond to secure payment of bail is not mandatory—judges may permit defendants to post various types of unsecured, but legally binding, pledges to forfeit property in the case of failure to appear.

However, these non-commercial bond options are reportedly the exception, and comparatively rare.[98] The statute also prohibits release on one’s own recognizance for any charge involving violence, distribution of drugs or possession with the intent to distribute drugs, any sex offense, or any domestic violence case.[99]

Statutory guidelines determine the amount of bail that include factors such as criminal history, employment status, and ability to pay. But with limited exceptions, there is no requirement that these guidelines be utilized.[100]

In September 2015 attorneys settled a lawsuit against Ascension Parish challenging the automatic imposition of bonds for traffic and misdemeanor offenses that led to detention for inability to pay, and a similar suit against Orleans Parish was pending at time of writing.[101] According to Marjorie Esman, director of the ACLU of Louisiana: “The [bail] system has led to an expansion of our jail system, simply by locking up people who can’t pay to get out.”[102]

At Orleans Parish Prison, the city is collaborating with the Vera Institute of Justice to address the problem of lengthy pre-trial detention that serves no criminal justice purpose (See Pre-Trial Detention Textbox).

In addition to bonds that create barriers to release, defendants in Louisiana criminal courts face fines, fees, and costs at every turn. In August 2015, the ACLU of Louisiana released a report entitled, “Louisiana’s Debtors Prisons: An Appeal to Justice,” documenting the fees, costs, and fines that criminal courts in eight Louisiana parishes impose, and the widespread incarceration of those unable to pay.

The ACLU found that despite the 1983 ruling of the US Supreme Court in Bearden v. Georgia that prohibits incarcerating offenders for failing to pay a fine if they genuinely lack the financial ability to do so, “courts in Louisiana routinely incarcerate people simply because they are too poor to pay fines and fees-costs frequently stemming from very minor, nonviolent offenses.”[103] In Bossier Parish, for example, the ACLU documented that judges issued 29 “pay or stay” sentences—which provide for the automatic incarceration of offenders who fail to pay regardless of whether they possess the financial means to do so— within a six week period.[104]

|

CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM IN NEW ORLEANS: PRE-TRIAL DETENTION The city of New Orleans is the site of several local initiatives that advocates hope will have a lasting impact in a city that for most of the last decade has had the highest incarceration rate in the US. With the help of the US Department of Justice and the Vera Institute of Justice, New Orleans has managed to reduce its per capita rate of incarceration by 67 percent since 2005. [105] In 2010, a coalition of city residents and non-profit organizations mobilized to reject a proposal for expanding the size of the jail, an institution under consent decree for overcrowded conditions. Law reformed followed, which included transferring possession of small amounts of marijuana, disturbing the peace, and other petty crimes into citations rather than detainable offenses. The project also identified two factors that drive over-reliance on bail as a condition of release. First, the criminal courts collected fees from each commercial bond, incentivizing judges to impose financial bail for minor offenses and that left many poor, low-risk people unnecessarily detained. [106] In addition, judges used no formal guidelines to evaluate the risk of flight or community harm in determining whether a defendant should be released while their case was pending. Describing the situation at Orleans Parish Prison, Vera Institute’s staff reported: Jails are meant principally to house defendants awaiting trial who pose a significant risk to public safety or of flight, but Orleans Parish Prison was used to detain thousands of pre-trial defendants because they did not have the means to pay a financial bond. There was no mechanism to assess defendants’ risk: judges set a bail amount based on the arrest charges and what was known of the criminal history and defendants either paid their way out or remained detained.[107] Since January 2012, Pre-Trial Services Program staff prepare a pre-trial report for every criminal district court felony defendant that is delivered to the prosecutor, defense attorney, and the court. This process has increased the release of low and moderate risk defendants through non-financial means from virtually zero to ten percent, with the vast majority of those defendants appearing for court dates and staying crime-free during the pre-trial period.[108] Reducing detention that is unrelated to public safety is good fiscal policy as well, as detention of one individual in OPP costs 50 dollars per day. Data from Vera, for example, show that from January-June 2013, the city unnecessarily detained low-risk defendants for a total of 8,510 days, at a cost to the city of $425,000. [109] |

Fredericka Wicker is a judge on the state’s Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal and former member of the Louisiana Sentencing Commission, which in 2012 recommended extensive reform of Louisiana criminal justice laws and policies. Judge Wicker told Human Rights Watch that although the state pays the salaries of the district court judges, in most district courts everyone else who works there, from clerks to cleaning staff, relies on local funding, a large portion of which is derived from court fees and fines.

According to Judge Wicker:

There is no question that the state funds its criminal justice system on the backs of people who get incarcerated…. People spend lengthy periods in pre-trial detention for inability to pay bail. Then they plead for time served just to get out. That results in what we call a ‘double bill’ as they are now no longer first time offenders, and the cycle perpetuates itself.[110]

The state’s public defender system is also in crisis due to lack of funding.[111] In 2014, public defenders represented more than 164,549 clients including 93 open capital cases.[112] Public defense in Louisiana is funded locally, and supported largely (66 percent) by assessment of court fees and costs, primarily via payment of traffic tickets.

According to state public defender Jay Dixon this source of support is insufficient, unstable, and unreliable. He said that when local revenues fall, as they did in 2015, public defender offices have no choice but to reduce services and establish waiting lists for public defense. As of January 2016, public defender offices in 12 districts were in fiscal crisis and four additional offices facing insolvency by the end of the fiscal year.[113]

In January 2016, the Orleans Parish Public Defender announced that services would be significantly reduced, including a refusal to take additional felony cases, due to “chronic underfunding,” and anticipated that this situation would persist either until attorney workloads decreased or funding increased. [114] Shortly after the announcement, the ACLU filed suit, challenging the state’s failure to adequately fund a system of public defense.[115]

Prisoners with mental health conditions also face prolonged detention in Louisiana, an issue that can impact access to HIV treatment and care.[116] Nationwide, one in 6male and one in three female jail prisoners suffer from mental health conditions ranging from psychosocial conditions to substance use disorders.[117]

Human Rights Watch has documented that jails and prisons in the United States have become de facto mental health facilities, housing three times as many individuals with mental health problems as do state mental hospitals.[118] On average, people with mental health conditions spend twice as long in detention as those not so diagnosed, due to factors that include inadequate community alternatives, lack of discharge planning, and disciplinary action taken against them for committing infractions while incarcerated.[119]

Studies show significant overlap between HIV and several major mental health conditions. People with depression and bipolar disorder, for example, are diagnosed with HIV at significantly higher rates than those without mental health issues, and treatment is often complicated by substance use.[120]

In Louisiana, access to mental health care has been limited by continuous state budget cuts since 2008, and the state ranks 47th of 50 in quality of and access to mental health care.[121] The national Treatment Advocacy Center estimates that people with psychosocial disabilities in Louisiana are nearly five times more likely to be incarcerated than hospitalized.[122] Jail officials throughout the state confirmed this trend.

In Lafayette Parish Correctional Center, for example, the number of inmates treated for mental health conditions increased by 72 percent between 2012 and 2014 and has more than quadrupled since 2006.[123] Similarly, an official at the East Baton Rouge parish jail said the facility has been “overwhelmed” by prisoners with psychosocial disabilities since the privatization of the LSU system and cuts to mental health services closed two local mental health facilities in 2013.[124]

According to Sgt. Darryl Honore of the Baton Rouge Police Department:

We used to bring folks with apparent mental illness and minor nuisance violations to LSU’s Earl K Long Hospital where they received appropriate care. But since Earl K Long closed we have no choice but to bring them to the jail.[125]

Medical staff at East Baton Rouge Correctional Center said that prisoners with mental health conditions are detained for lengthy periods pre-trial.

The situation is horrible for mentally ill inmates. They come in for public urination, exposure, things like that, and they stay for months, even years, because there is no other place for them to go. We had one [prisoner with psychosocial disabilities] here for 13 months.[126]

Baton Rouge attempted to raise money for a new mental health facility through a bond measure but voters rejected it in 2015. As of February 2015, city officials had partnered with a local private foundation to design and raise funds for a comprehensive mental health center which could offer police a voluntary alternative to arrest and incarceration but the timeline for this project was uncertain at time of writing.[127]

Push for Criminal Justice Reform

However, criminal justice reform has gained broader support in Louisiana. Recognizing that violent crime rates had not decreased and half of all people released from prison returned within five years despite the world’s highest reported incarceration rate and a $700 million corrections budget, the state Sentencing Commission in 2011 established a partnership with the Vera Institute of Justice and the Pew Center on the States to examine sentencing, parole, and probation procedures aimed at reducing the state prison population.[128]

In 2013 and 2014, the state legislature passed a series of criminal justice reforms including waiver of mandatory minimum sentences for some categories of crimes, reform of parole and probation procedures, increases in amounts of “good time” prisoners can earn toward release, and expansion of re-entry programs and alternatives to incarceration.[129]

Though many of its recommendations remain to be implemented, the commission’s work represented bipartisan support for sentencing and re-entry initiatives, and in 2015 the legislature authorized a statewide panel to broadly consider additional recommendations for criminal justice reform.[130]

While laws criminalizing marijuana that are among the most punitive in the nation remain on the books, Louisiana did take limited steps toward reform in 2015 when the legislature legalized medical marijuana for several diseases and made a second-possession offense a misdemeanor rather than a felony.[131]

In New Orleans, the Vera Institute is engaged in a long-term initiative focused on jail rather than prison as it attempts to reduce unnecessarily lengthy pre-trial detention.[132] As the following pages demonstrate, the continuation and expansion of these reform efforts are crucial for people burdened by both HIV and incarceration.

II. Findings

Barriers to HIV Testing, Treatment, and Linkage to Care in Parish Jails

The state Department of Corrections (DOC) identifies 104 correctional facilities as jails in Louisiana, excluding transitional work centers where partial restrictions are imposed on recently released prisoners.[133] Eleven are privately operated, under contract with sheriff’s departments or city governments in their parishes.[134] The remainder are operated directly by sheriff’s departments in each of the state’s 64 parishes, and by statute are funded by the local governing body, known in Louisiana as the “police jury” or parish commission.[135]

Human Rights Watch found that Louisiana parish jails offer limited access to HIV testing, treatment, and linkage to care: only 5 of the 104 jails provide some form of regular HIV testing, i.e., testing that is part of a formal program and not associated with discovery of HIV symptoms during a medical exam or in response to an individual request.

Treatment of HIV in parish jails is problematic, with widespread reports of interruptions, delays, and, in some cases, denial of medications. Linkage to care and services upon release, a critical component of public health efforts to improve outcomes and reduce new infections, is limited or non-existent at most parish jails.

HIV Testing in Louisiana Parish Jails

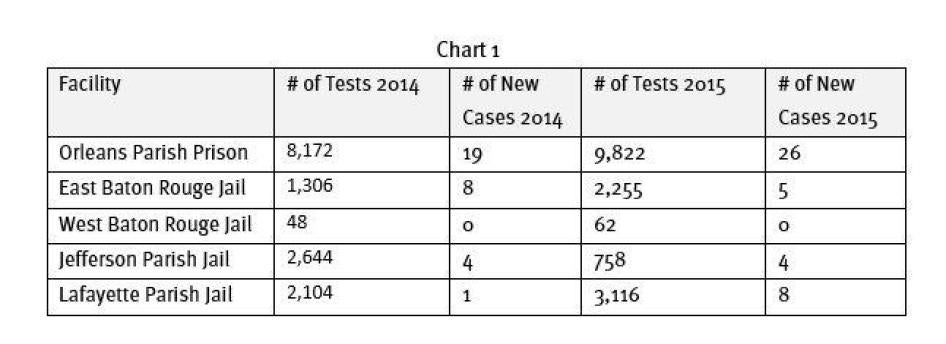

Five parish jails, all publicly operated, have some type of routine HIV testing program. New Orleans Parish Prison, Jefferson Parish Prison, East Baton Rouge Parish Prison, West Baton Rouge Parish Jail, and Lafayette Parish Correctional Center conduct HIV testing on a regular basis. [136]Two of those jails offer an “opt-in” approach and the other three provide prisoners with the option to “opt-out” of the HIV test .[137]

HIV testing is of particular concern in parishes with high prevalence of HIV infection. As noted above, most new HIV infections in Louisiana are located in the Baton Rouge, New Orleans, and Shreveport metropolitan areas. Four of the five parish jails with regular HIV testing programs are located in or near Baton Rouge or New Orleans; Shreveport has no correctional facility with an HIV testing program.

Baton Rouge

In the Baton Rouge metropolitan area, the HIV prevalence rate is the second highest in the state, and the rate of HIV infection ranks as the 4th highest in the nation. The area has four state prisons and nine parish jails that incarcerate more than 12,000 people. Baton Rouge-area AIDS service organizations estimated that one-third of their clients have a history of incarceration.[138] Yet testing is limited, with only two of the nine parish jails offering any type of HIV testing program.

As of December 2015, East Baton Rouge Parish Prison (EBR) housed approximately 1,400 prisoners: 90 percent were being held in pre-trial detention and the remainder were a mix of state DOC prisoners, parish-sentenced prisoners, and a few federal prisoners.[139] At EBR, incoming inmates are offered an HIV test and if a test is requested, they sign up on a list. The list is then given to a local AIDS service organization, Metro Health, whose staff come in three days a week to conduct the tests.

Metro Health staff reports that they are able to reach most people on the list to give them the test, as the medical staff gives priority to those who will be released first.[140] However, nurses told Human Rights Watch that they often are not aware when a prisoner will be released, an issue that hampers their ability to prioritize testing for people whose release is imminent.[141] In 2014, 1,306 inmates were tested at EBR with eight “new” positives (new HIV diagnoses) identified; in 2015, 1,394 inmates were tested at EBR with four “new” positives identified.[142]

West Baton Rouge Correctional Center (WBR) is a smaller facility, holding approximately 300 prisoners. As of December 2015, roughly 30 percent were pre-trial detainees, 50 percent state DOC prisoners, and the remainder federal prisoners.[143] Inmates are offered a test at intake, and those who request it are tested by Family Services of Greater Baton Rouge, whose staff comes in once a week. WBR conducted no tests in 2014 and 62 tests in 2015, finding one new positive.[144]

New Orleans

The other highly concentrated center of Louisiana’s HIV epidemic is the New Orleans metropolitan area, which has the highest rate of new HIV infections in the state, and the second highest rate of new infections in the nation.[145]

According to AIDS service organizations and HIV medical providers in the New Orleans Eligible Metropolitan Area, 15 to 30 percent of their clients have a history of incarceration.[146] The NOEMA comprises eight parishes with a total of nine jails, but only two parish jails in the NOEMA—Orleans Parish Prison and Jefferson Parish Prison—provide regular HIV testing.

In recent years, Orleans Parish Prison (OPP) typically held more than 3,000 prisoners in a sprawling complex. In 2013, a lawsuit alleging abusive conditions at the facility resulted in a consent decree that obliged the Orleans Parish Sherriff to improve conditions at OPP and to build a new facility to replace or supplement its capacity.[147]

The new jail facility, completed in 2015, has 1,400 beds, and as of February 2016 the population at OPP was in the process of being downsized as more prisoners were accommodated at the new site. As of December 2015 the OPP complex held approximately 1,400 prisoners.[148] As of December 2015, 79 percent of prisoners at OPP were awaiting trial, 19 percent were DOC inmates, and the remainder were parish-sentenced.[149]

HIV testing at OPP is provided on an “opt-out” basis, administered by medical staff as part of the medical screening upon entry. Another offer is made by medical staff within three to five days to those who have initially refused.[150] In 2014, OPP tested 8,172 inmates for HIV resulting in 19 new positives; in 2015, OPP tested 9,822 inmates resulting in 26 new positives.[151] Testing procedures will remain the same at the new facility. [152]

As of December 2015, Jefferson Parish Prison held approximately 1,000 prisoners: 92 percent pre-trial detainees, 6 percent parish-sentence, and the remainder DOC prisoners.[153] The Jefferson Parish Prison medical staff has been offering HIV tests to all incoming inmates on an “opt-out” basis as part of the initial medical screening since 2008. Medical officials at Jefferson told Human Rights Watch, “Every inmate is offered a test except if it’s Mardi Gras.”[154] In 2014 Jefferson Parish Prison tested 2,644 people and identified 4 new HIV infections; in 2015, 758 people were tested, and 4 new positives identified.[155]

The fifth jail offering regular HIV testing in Louisiana is Lafayette Parish Correctional Center (LPCC), located west of Baton Rouge in the center of the state. Originally built to house approximately 300 prisoners, as of December 2015 the LPCC had an average daily count of more than 800 prisoners, with 64 percent pre-trial detainees and 36 percent DOC inmates.[156] The Louisiana Office of Public Health reports that in 2013, the rate of new HIV infection in Lafayette Parish was significantly lower (19 per 100,000) than from East Baton Rouge Parish (48) or Orleans Parish (83).[157]

The LPCC has operated an HIV testing program since 2012, initially under a federal grant and now supported by parish funds.[158]Every inmate is told they will be tested for HIV unless they “opt-out.” Medical staff only conduct tests on Wednesdays, so prisoners may have to wait several days for the test depending on what day they enter the facility. Those who enter and exit between Thursday and Wednesday will not be tested.[159] In 2014, LPCC tested 2,104 inmates, resulting in 1 new positive diagnosis and in 2015, LPCC tested 3,116 prisoners, resulting in 8 new positive diagnoses.[160]

Data from these five parish jails reveal that their routine testing programs identify “new” HIV diagnoses in a very low percentage of cases, ranging from zero to .26 percent across the five jails in 2014 and 2015. This is consistent with findings from other HIV testing programs in large urban jails in the US.[161] Because jails have high rates of admission and release, often of the same persons in the same year, the number of tests conducted and the number of new diagnoses are often small percentages of annual admissions. [162]

Barriers to HIV testing

According to jail officials and medical staff, barriers to implementing or increasing access to HIV testing include a lack of adequate staff and funding for treatment costs. Staffing was frequently cited by smaller rural jails such as Claiborne Parish Detention Center in Homer, Louisiana, where the nursing staff told Human Rights Watch that they only test someone for HIV “if he is sick or if he asks for it for some reason,” explaining that they did not even have an infirmary, nor a doctor more than once a week.[163] Asked if Claiborne was currently holding any HIV-positive prisoners, a staff member responded, “Not to our knowledge.”[164]

In contrast, the East Baton Rouge Correctional Center has a relatively large medical staff comprised of a full time doctor who is an HIV specialist and holds an HIV clinic every two weeks, a health care manager, nursing director and 19 nursing positions providing 24 hour a day coverage. Asked why EBR does not offer an HIV test to all entering prisoners as part of their medical examination in order to avoid delay, the response from a medical staff member was clear: “We cannot afford to treat them if they are positive.”[165]

As it is, they explained, they are over capacity for treatment expenses, with more than 50 HIV-positive prisoners on anti-retroviral medications. EBR spent as much as $138,000 on HIV medications in one month in 2015, representing the majority of medication costs in an already strained health budget for the jail.[166]

Jail health budgets have felt increasing pressure since the partial privatization of the LSU hospital system. Prior to privatization, the LSU “charity” hospital system provided both primary and specialty care for state and parish jail prisoners, supported by state general fund appropriations. State prisons handled most primary care conditions in house, but utilized the LSU hospitals for specialty clinics, emergency care, and hospitalizations.[167]

Many parish jails relied even more heavily on the LSU hospitals for these services, for which they “never saw a bill.”[168] Expenses for medical care at EBR and parish jails throughout the state have risen significantly since the privatization of LSU hospitals, as this process has resulted in changes to the state mechanism for funding “offender care.”

Parish jails were always responsible for medication and pharmacy costs for treating prisoners in their custody, including for HIV medications. But other health care costs have increased since privatization. When the new private-public hospital renegotiated indigent care, including care for prisoners, responsibility for administering medical care to prisoners was transferred to the state Department of Corrections.

For the fiscal year 2014-15, the DOC received a $50 million appropriation from the legislature for management of “offender care” in the state, for expanding the capacity of medical facilities within the DOC, and to reimburse the newly privatized entities for specialty care for both state and parish jail prisoners.[169] However, the Department of Corrections designation of “specialty care” covered for parish jails excludes HIV, and a range of services such as OB/GYN care, dental, mental health, eye exams, laboratory tests, and x-rays. Since 2014, these expenses are now the responsibility of parish jails, with no state support.[170] A Lafayette Parish jail official said: “These increased expenses are difficult for even the big jails to deal with, and could put smaller jails under.”[171]

Determining what services would be reimbursed as “specialty care” under the new regime was the responsibility of Dr. Raman Singh, medical director of the Louisiana State Department of Corrections as part of the LSU hospital privatization process. According to Dr. Singh, “the LSU system disappeared overnight” and he was required to negotiate separate agreements with each new public-private partnership entity for “offender care.”

Using what he called a process “with no clear data—this was not science” on previous LSU costs for treating prisoners, Dr. Singh “worked with various people” to come up with an estimate of what offender care will now cost, and requested $50 million from the legislature to cover payments to the hospitals as well as plans for DOC to increase the services they provide onsite. The $50 million, said Dr. Singh, “could not cover everything, so many services such as HIV, dental, etc. were excluded.”[172] This decision now carries significant consequences for medical care in local jails, including services relating to HIV.

For example, increased medical expenses were cited as the main reason there is no HIV testing program for prisoners in Caddo Parish, home to the city of Shreveport. Caddo Correctional Center has around 1,100 prisoners, with 68 percent pre-trial detainees, 26 percent DOC inmates, and the remainder parish-sentenced or federal prisoners.[173]

The city of Shreveport had the third-highest number of new HIV infections in the state in 2013, and local AIDS service providers estimate that 25-50 percent of their clients have a history of incarceration.[174] Yet when asked why the jail had no HIV testing program, the jail’s director of health services stated that the facility “cannot afford to treat someone who was identified as HIV-positive. It sounds cold, I know, but that is the reality.”[175]

Staff of the Caddo Parish Commission, the entity responsible for providing funds for the Caddo Correctional Center, confirmed that budget pressure prevented the jail from operating an HIV testing program. [176] The commission’s finance officer told Human Rights Watch that the commission was having trouble just paying for the medications for the seven prisoners that they knew were HIV-positive as of April 2015. She added that medical expenses have risen nearly 20 percent since 2012 due to specialty care costs that are no longer covered.

HIV medications have always been the responsibility of the local parish jail, but other specialty costs—clinic visits, lab tests, and other expenses—are excluded from reimbursement under the state’s new “offender care” system.[177] Sheila Wright, Caddo Parish Correctional Center’s director of health services, told Human Rights Watch that she disagreed with the DOC’s exclusion of HIV from specialty care: “If I had HIV, my care would be specialty care.”[178]

Routine HIV Testing before Release

Fear of high treatment costs on the part of parish jails is understandable. While testing itself is not expensive, and the Office of Public Health provides free rapid testing kits, HIV treatment requires a series of diagnostic tests that can range from $300-500. Anti-retroviral medication can cost as much as $4,500 per month.[179] Privatization of the LSU hospitals and the exclusion of HIV treatment as an expense reimbursable by the state has added pressure to local jail budgets for health care.

Cost, however, does not excuse the authorities’ failure to provide incarcerated people with HIV testing and treatment services equivalent to those available in the community. Although incorporating routine rapid HIV testing as part of initial medical screening conducted by medical staff is preferable due to the fluidity of jail admissions and releases, there are steps parish jails can take to promote the health of individuals with HIV and support public health with minimal expense. [180] According to national experts on HIV and incarceration, one such approach would be to conduct routine voluntary HIV testing for every inmate prior to release. Working with a community AIDS service provider to conduct the tests would reduce cost and enhance linkage to care.[181]

In 2015, Louisiana adopted a law that requires DOC to offer HIV testing on an “opt-out” basis to every prisoner being released from a state operated prison facility or state privately operated prison facility, with a requirement that if a prisoner tests positive, they shall be referred to appropriate care and services.[182] This requirement should be extended to parish jails.

As of January 2016, the Louisiana Department of Corrections housed 525 prisoners living with HIV; in 2010, the prevalence of HIV in Louisiana state prisons was 3.5 percent, the second highest in the country.[183] The DOC provides “opt-out” HIV testing at each of its two intake units, Hunt for men and Louisiana Correctional Institute for Women.[184]

DOC, however, conducts no HIV testing at parish jails. The DOC’s testing program for HIV is applicable only to prisoners assigned to one of its nine correctional facilities or one of the three privately operated state prisons, and is not implemented for the approximately 18,000 DOC prisoners serving their sentences at parish jails.[185]

DOC prisoners in most parish jails will only be tested if they pass through a DOC facility at some point, or proactively request an HIV test at a parish jail that offers testing. DOC is currently negotiating a possible pilot program with one parish jail, a privately run facility, for providing HIV testing to its DOC prisoners. However, a DOC official told Human Rights Watch that the jail is reluctant to start an HIV testing program for fear of treatment costs, despite the DOC’s assurance that any prisoners testing positive will be transferred to one of its nine facilities.[186] The absence of HIV testing programs in parish jails increases the likelihood that a number of HIV-positive DOC prisoners will remain unaware of their status.

HIV Treatment in Louisiana Jails

Human Rights Watch found that HIV treatment and care in Louisiana parish jails is inadequate and problematic in several respects. Because so few jails offer HIV testing on a regular basis, the vast majority of jails treat HIV only upon self-disclosure, when an individual becomes symptomatic and then tests positive for the virus, or in some cases when a prisoner proactively requests an HIV test that then comes back positive.

And as described below, even in cases where jails know a prisoner is HIV positive, our research documented numerous allegations from people recently in jail as well as from AIDS service organizations, public defenders, and advocates of treatment being delayed, interrupted, and denied altogether during incarceration. These reports concerned facilities both rural and urban, small and large, those with testing programs and those with none.

Treatment Interrupted, Delayed, or Denied

Human Rights Watch found treatment to be problematic in multiple ways, in jails throughout the state. Many people who were on HIV medications said that they encountered problems continuing their regimens while incarcerated.

In small rural jails, several people reported being told by jail officials that they would not receive HIV medication because of the cost.

Jane, 53, a mother of four, had been held at Ouachita Parish Jail. She said that jail authorities told her, “You’d better get family or someone to bring those medications in, because you’re not going to get them here, they’re too expensive.”[187] Jane was released after seven days of detention, during which time she went without her medications.[188]

Adrian, 31, said a prosecutor at the Allen Parish District Attorney’s office told him he would not receive his HIV medications in jail.[189] Bob, recently released from Natchitoches Parish Prison, said his cousin was still in the jail trying to get his HIV medications. “His old lady is trying to get them to him but they won’t let her. He has been in there for 25 days.”[190] David, 49, told Human Rights Watch that he was in Ascension Parish Jail for 30 days without any HIV medications. “I self-disclosed, I was trying to get my friend to bring me my meds from my house, but he wouldn’t bring them. The jail, I guess, was waiting for my friend to bring them, but he never did. So I spent 30 days without my meds.”[191]

AIDS service organizations throughout the state confirmed that many of their clients who entered jail on HIV medications encountered serious problems. One case manager at Central Louisiana AIDS Support Services in Alexandria said one in five clients has a history of incarceration, but “they don’t get their meds in jail.”[192] She described one client who entered Rapides Parish Prison and “they let her son bring her medications until they ran out, but that was it. She wasn’t released for some time after that…”[193]

A case manager at GO CARE AIDS service agency in Monroe told Human Rights Watch:

I had a client call me two weeks ago from Richland Parish Prison. He said, ‘They won’t give me my meds.’ He said, ‘I have a possible sentence of two years, am I going to have to wait two years for my meds?’[194]

Another case manager at GO CARE said she had a client in Caldwell Parish Prison for two years who did not receive his medications the entire time he was there. “As soon as he came out, we got him back on meds,” she said.[195]