(New York) – The Thai government should urgently take the final steps to ratify the international convention against enforced disappearance, Human Rights Watch said today. The government should also end all delays in passing implementing legislation to criminalize torture and disappearances.

On March 10, 2017, the military-appointed National Legislative Assembly unanimously approved ratification of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, which Thailand signed in 2012. However, the government has not yet set a clear time frame for either depositing the treaty with the United Nations secretary-general as required, or reconsidering and enacting the Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearance Bill, which the assembly rejected in late February.

Thailand is scheduled to appear before the UN Human Rights Committee on March 13 and 14 to defend its record on civil and political rights.

“The Thai government should finally ratify the disappearances convention and enact the criminal law needed to fully prosecute officials responsible for heinous crimes,” said Brad Adams, Asia director. “After years of waiting, more promises are simply not enough. The government needs to take swift and concrete action to enact a law that severely penalizes torture and enforced disappearance.”

The Prevention and Suppression of Torture and Enforced Disappearance Bill, if passed, will be the first Thai law to recognize and criminalize torture and enforced disappearance, whether committed inside or outside of Thailand. Importantly, the current draft provides no exemptions or immunities for acts committed during states of emergency or other extraordinary circumstances. Those convicted of either torture or enforced disappearance would face a minimum sentence of 20 years in prison, extending longer in cases of serious injury or death. Commanders or supervisors who intentionally ignore such crimes will also face prison terms.

The government needs to take swift and concrete action to enact a law that severely penalizes torture and enforced disappearance.

Brad Adams

Asia Director

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly urged successive Thai governments, including in a January 14, 2016 letter to Prime Minister Gen. Prayut Chan-ocha, to ratify the Convention against Enforced Disappearance and to amend its penal code to make enforced disappearance a criminal offense. Following the military coup in May 2014, Human Rights Watch has raised serious concerns regarding the government’s use of secret military detention authorized under section 44 of the 2014 Interim Constitution (against political dissenters and suspects in national security cases), as well as the 1914 Martial Law Act and the 2010 Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations (against insurgent suspects in the southern border provinces).

Enforced disappearance is defined under international law as the arrest or detention of a person by state officials or their agents followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty, or to reveal the person’s fate or whereabouts. Enforced disappearances violate a range of fundamental human rights protected under international law, including prohibitions against arbitrary arrest and detention; torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment; and extrajudicial execution.

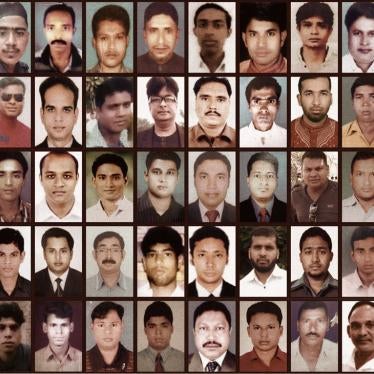

Since 1980, the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances has recorded 82 cases of enforced disappearance in Thailand, including the disappearances of prominent Muslim lawyer Somchai Neelapaijit in March 2004, and ethnic Karen activist Porlajee “Billy” Rakchongcharoen in April 2014. None of these cases have been successfully resolved. Human Rights Watch and other human rights groups working in Thailand believe that the actual number of such cases in Thailand is higher because some families of victims and witnesses remain silent for fear of reprisal, and because the government lacks an effective witness protection system.

Torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment are prohibited under international treaties and customary international law. Since October 2007, Thailand has been a party to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which specifically places an obligation on governments to investigate and prosecute acts of torture and other ill-treatment. Under the Convention against Torture, any statement made because of torture “shall not be invoked as evidence in any proceedings, except against a person accused of torture as evidence that the statement was made.”

Successive Thai governments have dismissed allegations that the military, police, or other security forces tortured and ill-treated detainees. Despite failing to provide evidence to refute allegations, the authorities have frequently attacked their accusers by alleging those complainants made false statements with the intent of damaging Thailand’s reputation.

Thailand’s scheduled March appearance before the UN Human Rights Committee would be a moment to assess the government’s seriousness in tackling disappearances and improving human rights.

“If Thailand wants to convince the Human Rights Committee that it is seriously addressing torture, disappearances, and other grave abuses, it will need to do more than say what it is planning to do,” Adams said. “Thailand is only going to end its long record of failure by ratifying the disappearances convention, enacting strong legislation, and fully investigating and prosecuting torture and disappearance cases to break the cycle of abuses and impunity.”