Europeans who want to see a better future for Syrian refugee children can be proud: the European Union has given hundreds of millions of euros to help them go to school in the beleaguered countries near Syria.

But good luck tracking where that money went, and whether it is being used to address key problems preventing Syrian children from going to school.

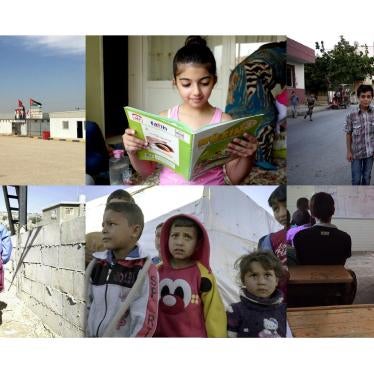

The challenge of educating Syria’s displaced children is on stark display in Lebanon, which hosts more refugees per capita than any other country.

As of September, there were almost half a million school-age Syrian refugee children in Lebanon. More than half of them were out of school.

A clearer accounting of the EU’s contributions would also give Brussels more leverage to push Lebanon to improve how the aid money is spent and fix policies that are keeping Syrian children from getting to school.

In February, Lebanon pledged to get all children, Lebanese and Syrian, into school by the end of this academic year. Under its five-year education plan, that will require aid of around €331 million per year from donors.

The recent “compact” between the EU and Lebanon endorses this plan.

The EU has committed to give €400 million to Lebanon in 2016 and 2017, and has already given more than €1 billion in aid to Lebanon since the Syria conflict began, including €188 million for education and child protection.

But there is little public information on the specific projects this funding is supporting.

Our research has highlighted the problems Syrian children face when trying to go to school in Lebanon, and they are daunting.

The vast majority of Syrian refugees in Lebanon are poor and in debt; the UN refugee agency said on 22 November that 88 percent of Syrians had lacked food or money to buy food in the previous month.

Yet Lebanon requires every Syrian refugee aged 15 and above to pay $200 a year to renew their residency permit.

Refugees are often required to obtain Lebanese “sponsors”, who sometimes demand large payments. Since Lebanon imposed this residency policy in 2015, about 70 percent of Syrian refugees have lost their status.

The residency policy is exacerbating poverty and making it harder for children to attend school. Fearing arrest and possible deportation if they move around in search of informal, low-wage jobs, many Syrian refugees depend on their children to work because the children can move around more easily.

In addition, the curricula in Lebanon are largely English and French, languages with which Arabic-speaking Syrian children are often unfamiliar, yet language training is seldom available.

And even if parents try to send their children to school, transport costs are often a barrier. All of this may explain why Syrian enrolment rates in secondary education in particular are low.

But it is almost impossible to find out which issues EU aid is targeting to help bring Syrian refugee children back to school.

We know that the EU’s Madad Fund has given more than €232 million for schooling in Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan and that the European Neighbourhood Instrument provided €250 million for basic services in Lebanese communities.

But neither of these instruments provides a detailed breakdown of where that money is actually spent.

Echo, the European Commission’s humanitarian arm, does have a fund-tracking database and has allocated €87 million to Lebanon in 2016, but there are no entries on education funding there.

More transparency would help EU taxpayers ensure their money is spent to remove critical blockages preventing Syrian children from going to school.

It would also put the onus on Lebanon to explain why a quarter-million refugee children are still out-of-school despite international support.

In its compact with the EU, Lebanon merely commits to consider “periodical waiver of residency fees” and steps to ease refugees’ access to the job market “in sectors where they are not in direct competition with Lebanese”.

No timelines, no benchmarks. These vague commitments are not good enough.

It’s in everyone’s interest for Syria’s youngest generation to enjoy their right to education and acquire the knowledge and skills they will need to contribute to the economies of their countries of asylum and ultimately to help rebuild Syria.

It is in Lebanon’s own interest to abolish impossible requirements that deprive Syrian refugees of their status and keep their children out of school.

Europeans would have more leverage to push for needed change if the EU published detailed, timely, and comprehensive information about its support to countries wracked by Syria’s misery.