In theory, we can do it [increase women’s participation in the peace talks]. But in practice it’s difficult. So, we made a “gentleman’s agreement” to wait until later.

—Ethnic Armed Organization representative, Myitkyina, May 2016

Women make up just over half of the population in Burma, but have been noticeably absent from nearly four years of peace negotiations to end armed conflict in the country. Beyond women holding few, if any, senior positions in the parties involved in these negotiations, many women’s groups report being treated with disdain or as “spoilers” for pressing for the inclusion of women’s rights.

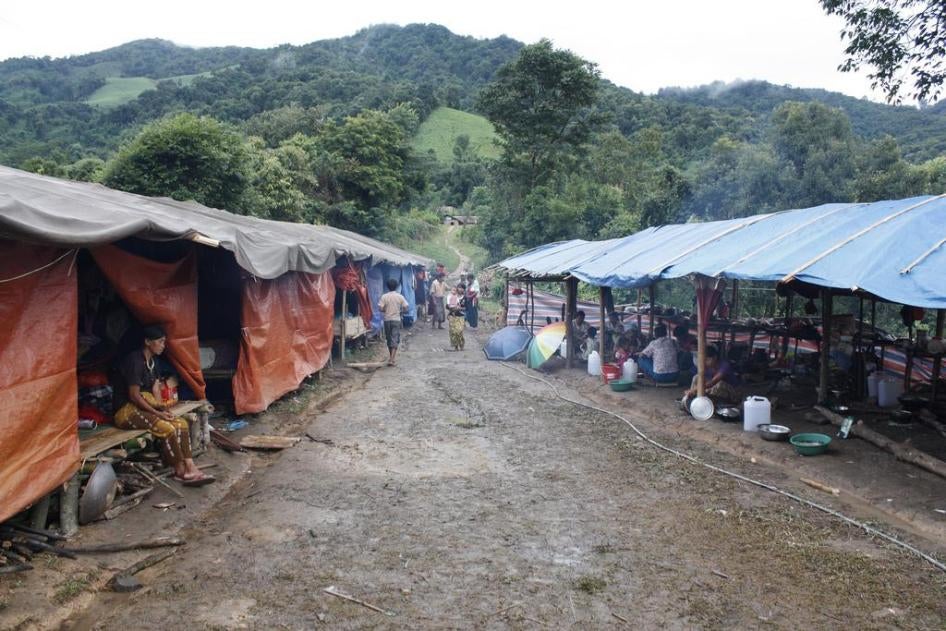

Burma has endured a number of prolonged internal armed conflicts since its independence in 1948, with three of the country’s seven ethnic-minority states facing ongoing fighting or tensions. In recent years the fighting in several parts of the country has worsened, with escalating violence in Kachin and Shan States resulting in countless civilian deaths and injuries, and the protracted displacement of over 200,000 people.

Over the years, negotiations between the government and ethnic armed groups have resulted in a number of ceasefire agreements. In October 2015 a partial nationwide ceasefire was concluded with eight non-state armed groups, while many others still maintained bilateral ceasefires, some over 20 years old.[1] But these agreements have so far not ended the violence nor created the conditions necessary for displaced people and refugees to return home.

In November 2015, the National League for Democracy (NLD) party led by opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi won a sweeping victory in nationwide elections. In April 2016, Aung San Suu Kyi announced a revamped peace process labelled “Panglong 21st Century,” a reference to the Panglong Agreement of 1947 signed by some of Burma’s ethnic groups and Suu Kyi’s father, Burma’s independence leader Gen. Aung San.[2] This new process is scheduled to be unveiled in August.

International human rights law and the principles contained in United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 and subsequent resolutions on women, peace and security obligate governments to take steps to remove discrimination against women in public life and ensure their right to take part in the conduct of public affairs.[3] These should set the standard for the essential role of women in Burma in the prevention and resolution of conflicts, including in peace negotiations, peace-building, peacekeeping, humanitarian response, and in post-conflict reconstruction.

Women in Burma need a greater role in the peace process not only because they suffer many of the consequences of the conflict, but also because their participation can best ensure that the full range of human rights concerns is addressed in any peace agreement. Addressing the human rights issues that are frequently at the core of conflicts, particularly those with an ethnic component, can be crucial for obtaining a long and durable peace.

Historical Context

Modern Burmese history has been characterized in large part by armed conflict, both national and local. Since achieving independence from Britain in 1948, Burma has struggled to establish governance that respects fundamental human rights. Decades of armed conflict between the central government and various ethnic armed groups have been accompanied by countless violations of the laws of war and human rights abuses that have adversely affected millions of predominantly marginalized people. The legacy of misrule includes the fundamentally flawed 2008 constitution, which was designed to limit civilian reform and ensure residual constitutional powers for the Tatmadaw (national armed forces).

After independence, Burma underwent a post-colonial political reformation marked by nascent democratic rule, political instability, and ethnic armed conflict. This reformation was curtailed with the 1962 coup by the army and the introduction of military rule that would last for over 60 years. Throughout the period of military rule and up to the present—which is still marked by a military-dominated parliament—the Burmese army has committed numerous violations of international human rights and humanitarian law during popular uprisings against the military government and in ethnic-minority areas. These include killings, rape, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, forced labor, land confiscation, use of child soldiers, and other abuses. To a lesser degree, ethnic armed groups have also been implicated in human rights abuses, including the use of child soldiers, forced labor, and torture and ill-treatment.

After more than 50 years of repressive military rule, the government that came to power in March 2011 took significant steps to improve human rights: it released hundreds of activists, students, monks, and other political prisoners; eased media restrictions; and passed laws on freedom of assembly and labor union formation. However, as Human Rights Watch has documented in Kachin, Shan, and Arakan States, as well as in other areas, the political transition that began in 2011 did not bring an end to serious abuses.[4]

The November 2015 elections resulted in a further transfer of political power from the military to a civilian government, although the military retains a large presence in the political and economic systems. The military-drafted constitution empowers the armed forces to appoint the defense and border affairs ministers, as well as the home affairs minister—who controls the police. An unreformed judiciary remains corrupt, incompetent, and subordinate to the military. Thus, the military remains outside of civilian control, and benefits from complete impunity for past and ongoing crimes. Renewed fighting has displaced thousands of civilians amid allegations of serious laws-of-war violations by government forces and ethnic armed groups, including forced labor, torture and ill-treatment, and sexual violence against women.[5]

Women and their Rights in Burma’s Conflict

Impact of the Conflicts on Women

Women in Burma have long been targeted for abuse during the country’s many internal armed conflicts. Sexual violence by the Tatmadaw, and to some extent ethnic armed groups, has been frequent.[6] Persistent abuses against civilians, including sexual violence, have been facilitated by the lack of accountability for such crimes. Local and international human rights groups have reported numerous cases of alleged sexual violence that the military has refused to seriously investigate.[7] The Ministry of Defence informed the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in Burma that the military prosecuted 61 armed services personnel for rape between 2011 and 2015—but provided few details on convictions or punishments.[8] Where investigations and prosecutions do occur, many proceedings take place in military courts that lack independence from the chain of command and are rarely, if ever, open to the public.[9]

For example, in January 2015, the bodies of two ethnic Kachin teachers, Maran Lu Ra, 20, and Tangbau Hkawn Nan Tsin, 21, were found in Shan State, where villagers and activists allege they were raped and then brutally murdered by Burmese army soldiers.[10] Local activists, international nongovernmental organizations, and the United States government called on Burma to investigate the cases. In May 2016, the Tatmadaw made public statements saying that an investigation had taken place, but there has been no information about charges being brought against suspects or about any trial, let alone convictions.[11]

In addition to being targeted for sexual violence and other abuses, women and girls have often been impacted by armed conflict in other specific and disproportionate ways. As the UN secretary-general, Ban Ki-moon, noted in 2016:

Sexual violence has been exacerbated by conflict and displacement, notably in Kachin and northern Shan States, linked to the collapse of social protection mechanisms, the increased presence of armed actors, and military camps in proximity to civilian centres. … A rise in trafficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation and forced marriage was noted, with 45 cases recorded early in 2015. Stateless women and those who lacked identity documents were at greatest risk, including while travelling on crowded boats and staying in smugglers’ camps.[12]

Abductions and enforced disappearances of women in conflict zones are also an ongoing concern, such as the case of a Kachin woman, Sumlut Roi Ja, believed to have been abducted by Burmese army troops in October 2011, whose fate is still unknown.[13]

The displacement of civilian populations during the fighting has had multiple distinct impacts on women and girls in Burma. Although data is scarce, the UN Population Fund notes that displacement:

[H]as resulted in a lack of access to livelihoods for affected populations, forcing many of the men to seek work away from their families. Their prolonged absence has a profound effect on the safety and security of women and girls. … recent reports indicate that GBV [gender based violence], including sexual violence, are a constant fear and threat.[14]

Women and girls also face added security risks connected with the impact of armed conflict on their families. Men who join military forces, are conscripted, or are taken as forced porters to carry supplies in combat zones leave behind women and children to fend for themselves in their communities. Reports show that this places women at increased risk of abuse from the military and armed groups. In Shan State in 2016, after the Tatmadaw detained a number of young men, many villagers—including the remaining men—fled. Left behind were 12 women who had the responsibility of guarding their homes, possessions, and food. One women said, “I feel so scared living here while my husband is away, but I have to look after my house. I do not know what we will do to defend ourselves if the Tatmadaw come again.”[15]

Women and Armed Conflict

For example in the negotiations, women are there in the dining room, in reception. Women ushered in the guests, they received people. Women’s role is to ease tensions. Women’s role is not in the meeting, it is outside the conference. The armed parties are in very defensive positions, and women can ease this. Women are not negotiators, are not diplomatic actors.

—Ethnic Armed Organization representative, discussing efforts to include women in the peace talks, Myitkyina, May 2016

The role of Aung San Suu Kyi notwithstanding, the limited presence of women in Burmese politics and their relegation to a marginal role, or “tea break advocacy” as women’s rights activists in Burma termed it, does not reflect either their participation in the armed conflict as members of armed groups or in efforts to bring peace.[16] As one female politician told Human Rights Watch:

There is a particular burden for women: military leaders only count those who have been in [military] service. …Women get married, have children. They have responsibility for the family. This makes it impossible to stay in service. Men just go to the frontline.[17]

Data on female fighters is difficult to obtain, but many women have participated in ethnic armed groups over the years. In Kachin State, “women participate as soldiers or military-trained members of the civilian administration of the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), the political entity that is seen as representing the Kachin people. The military wing of the KIO, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), is currently the only non-state armed group in Myanmar that actively drafts women.”[18] As one researcher recently wrote, “All women interviewed agreed that women should be allowed to fight on the frontline if they so wished, and several of the younger [female] recruits stated that they would like to engage in combat. Some had lobbied their superiors to get access to combat positions.”[19]

The Tatmadaw have actively recruited women as well. In 2013, the Defence Ministry ran advertisements seeking to recruit Burmese women, noting that “successful candidates will be spared from serving on frontlines and instead be offered posts as second lieutenants.”[20] In January 2014 the military appointed just two junior female officers to serve as members of parliament (MPs).[21] Altogether, 166 parliamentary seats (or 25 percent) are reserved for Tatmadaw officers—a controversial measure put in place as part of the political transition.

Women’s Role in Resolving Conflict in Burma

Long before political change came to Burma, women have been at the forefront of activism demanding a democratic transition, including respect for women’s rights. They have mobilized around the issue of their participation in the peace process. This has not, however, translated into women’s meaningful representation in ongoing peace efforts and has not resulted in women’s rights being included in negotiations. Instead, women’s rights concerns are often dismissed.[22] A women’s rights representative told Human Rights Watch that women have the capacity to contribute, but are excluded at every turn.[23] A female political representative told Human Rights Watch, “decision-makers are only men, who only send invites to other men. It is hard to change decades of these habits.”[24]

The peace processes in Burma are complex, and, as in most conflict resolution efforts, are evolving even as the negotiations are underway. Many of the conflicts and their respective peace efforts are related to the ethnic groups, or ethnic armed organizations, in various states, and various bilateral ceasefires have been signed (and broken) between the government and these organizations. A number of these bilateral ceasefires are monitored by local community ceasefire monitoring mechanisms.[25]

Beginning in 2013, the government of then-President Thein Sein undertook negotiations on a Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement. During the negotiations, the government renewed major military operations against the armed wing of one of the largest ethnic armed organizations, the Kachin Independence Army. [26] After years of stop-and-start negotiations, in October 2015, 8 of the 16 government-recognized ethnic armed organizations signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement. This was an initial step in a broader peace process that is meant to proceed at least through 2016.

Women have had little or no participation in these peace talks. On most peace process committees and bodies of both government and ethnic armed groups, women have been completely excluded. In only one case has women’s participation approached being significant: in the complex set of negotiations leading up to the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement, there were 2 women on the 14-member Senior Delegation, the negotiation body for the ethnic armed organizations. This included Naw Zipporah Sein, the appointed lead negotiator, and Saw Mra Raza Lin.[27] A newly appointed secretariat to oversee the peace process, the National Reconciliation and Peace Center (NRPC), a reformation of the contentious Myanmar Peace Center, has two women among its eleven members: NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi, and Shila Nan Taung, a Kachin MP in the national upper house.[28]

One female politician told Human Rights Watch that the male leaders of ethnic armed organizations say, “We are considering, we are watching” when pushed to ensure a more inclusive delegation.[29] As one women’s rights activist told Human Rights Watch, what she called “tea break advocacy” is often the only space for women to influence ongoing negotiations, meaning women are not able to participate in the formal decision-making discussions, but are relegated to trying to convince delegation members during the breaks in the meetings—as delegates get their tea.[30]

The exclusion of women is particularly noticeable in negotiations regarding security sector reform, demobilization and disarmament of armed groups, and ceasefire and ceasefire monitoring. The male negotiators on these “hard security” matters have routinely dismissed the relevance of women’s rights and presence in negotiations. The representative of one ethnic armed organization told Human Rights Watch:

Women’s role is to ease tensions. The armed parties are in very defensive positions, and women can ease this. Women are not negotiators, they are not diplomatic actors. The negotiations now are military to military. When the government is involved, then women will participate.[31]

Violations of human rights have been central to the waging of the conflict, including abuses against women. Ceasefire provisions will also have a major impact on affected communities, including livelihoods, education, housing, and health care—matters that will be of particular concern to women. The failure of ceasefire agreements to address these issues in a rights-respecting, non-discriminatory manner could have a far-reaching impact, including ensuring that the agreed-upon peace will be stable and durable.

Current numbers of women and men in the peace process – 2011 – 2016 [32]

|

Entity |

Year |

Total Number of Participants |

Number of Female Participants |

Number of Male Participants |

|

Union Peacemaking Central Committee (UPCC) |

2012 |

11 |

0 |

11 |

|

Union Peacemaking Working Committee (UPWC) |

2012 |

52 |

2 |

50 |

|

Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team (NCCT) |

2013 |

16 |

1 |

15 |

|

Joint Implementation Coordination Meeting |

2015 |

16 |

0 |

16 |

|

Union Peace Dialogue Joint Committee (UPDJC) |

2015 |

48 |

3 |

45 |

|

Joint Ceasefire Monitoring Committee (JCMC – Union Level) |

2015 |

26 |

0 |

26 |

|

Senior Delegation (SD) |

2015 |

15 |

2 |

13 |

|

National Reconciliation and Peace Centre (NRPC) |

2016 |

11 |

2 |

9 |

With some assistance from supportive governments and from international nongovernmental organizations, female negotiators, politicians, and activists are asserting the importance of their meaningful participation in ongoing talks.[33] For example, the Peace Support Fund, a donor government fund that supports “initiatives which increase trust, confidence, engagement and participation in the peace process in Burma, and which reduce inter-communal tensions,” includes “the needs and interests of women” as a mandatory criteria for the projects it supports.[34] As one Kachin women’s organization representative told Human Rights Watch, “We want to be at the decision-making table, including the ceasefire talks—at every single stage.”[35]

Some women participating in the talks have called for a 30 percent quota for women’s participation in all negotiations. The quota has been a subject of considerable discussion and disagreement, including in the preparatory discussions among ethnic armed organizations for the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement. In these discussions, some male members of the armed groups wanted to make the 30 percent quota a ceiling—that is, the maximum level of women’s participation, rather than a floor, the minimum level. As one ethnic armed organization representative told Human Rights Watch, the final language of the ceasefire agreement suggesting a 30 percent quota was ignored by both armed opposition and government negotiators. “In theory, we can do it,” said this representative. “But in practice it’s difficult. So, we made a ‘gentleman’s agreement’ to wait until later to ensure women’s participation.”[36] One women’s rights activist said that the parties were not taking women’s participation seriously: “They don’t say, ‘the Women’s League of Burma are coming,’ they say, ‘Oh the 30% are coming.’”[37]

The somewhat increased role of women in Burma’s new government may help open the door for their greater role in peace negotiations. Women have been historically excluded from participation in the Burmese government, long a bastion of the military. Some progress has been made and the parliament elected in November 2015 has more women MPs than at any time in Burma’s history, although the number is still low. Sixty-six of the MPs in the Union parliament (10 percent) are women and reportedly about 13 percent of seats in state and regional assemblies are filled by women. Five out of twenty-nine ethnic affairs ministers elected in the regional assemblies are women, and women were selected as chief minister for both Tenasserim Region and Karen State. The 18-person cabinet of the national government has, however, just one woman: Aung San Suu Kyi herself.

The new NLD-led government so far has not provided leadership in putting forth female candidates. If they had continued with the ratio of female candidates they had put forward in the 2012 by-elections to fill 45 seats, one analysis estimates the overall number of women MPs would be approximately 121. NLD spokesperson Win Htein told The Myanmar Times that “the reason the party had not put forward more female candidates was that many of the women were ‘green’ and ‘inexperienced.’” He said cultural and religious traditions in Burma meant “women were not confident in political situations.”[38]

Current Status of Women’s Rights in Burma

As the CEDAW Committee has stated, and as Burmese women’s rights organizations repeatedly highlight, justice for women and girls in Burma remains elusive, particularly with regard to violence related to armed conflict.[39] There is no institutionalized complaint mechanism for victims of sexual violence perpetrated by the Tatmadaw, consistent with the UN Declaration of Commitment to End Sexual Violence in Conflict, which the government signed in 2014.[40] When Tatmadaw soldiers are involved in abuses against civilians, victims and their families must rely on the Tatmadaw to initiate proceedings against its soldiers. Despite allegations of more than 70 cases of sexual violence perpetrated by the Burmese army over the past 4 years, few prosecutions have been publicly reported; in 2014 only two soldiers were known to have been convicted of rape.[41] Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, in the Burma section of his 2015 report on conflict-related sexual violence, noted that “legal recourse needs to be available uniformly and systematically” and that special rapporteurs on Burma had called for the constitution to be amended so that security forces are subject to civilian oversight.[42]

More generally, Burmese criminal law provides inadequate protections to women. There is no specific law criminalizing violence against women at home or sexual harassment in the workplace, nor does current law allow women to seek protection from the state, including restraining orders on violent men.[43] The secretary-general’s 2016 report on conflict-related sexual violence called on the Burmese government “to adopt a comprehensive law to address violence against women and to uniformly enforce the Defence Services Act (1959) so that military perpetrators can be prosecuted transparently.”[44]

The Protection and Prevention of Violence Against Women (PVAW) Law, the draft of which was the result of extensive consultation with Burmese women’s groups and the UN, has apparently been weakened significantly in recent consultations in the new Parliament. Some suggested amendments would cause the law to fall short of Burma’s commitments to international human rights standards, including the need to include a broad definition of rape and specifically outlaw domestic violence and marital rape.[45] If passed, a strong and comprehensive law on violence against women would represent an important improvement over previous piecemeal legislative reforms in this area, and could spur reform of other laws that discriminate against women.

The development of the National Strategic Plan for the Advancement of Women, 2013-2022 (NSPAW) was positive, but its implementation has stalled with the new government. Launched after three years of consultation with civil society, the plan was partially in response to the social havoc wreaked by Cyclone Nargis in 2008.[46]

Due to the political sensitivities of the previous government and the Tatmadaw regarding the ongoing conflicts, distinct issues related to safety and security for women and girls due to armed conflict are absent from NSPAW. Burmese women’s rights organizations have advocated for the government to address this gap by adopting a concerted national strategy on gender and conflict, either through amending NSPAW or through developing a new plan.

These efforts at reform are making halting progress. But the new government also needs to address laws enacted by the previous Thein Sein government that curtail the rights of women and girls. The Monogamy Law, for example, contains provisions that criminalize consensual sexual relations between adults, regardless of marital status, violating the right to privacy protected under article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Laws criminalizing consensual sex disproportionately impact women—for example, a rape victim may be deterred from filing a criminal complaint if the failure to win a conviction puts her at risk of prosecution for adultery. The UN Working Group on Discrimination against Women in Law and in Practice, which is tasked with identifying good practice on the elimination of laws that discriminate against women, stated in 2012 that adultery should not be a criminal offense and noted its often disproportionate impact on women.[47]

Recommendations

To All Parties to Burma’s Nationwide and Bilateral Negotiations

- Ensure full and substantive participation of women in all future peace negotiations, as committed to by government and ethnic armed groups in the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement.

- Ensure women’s rights organizations have a significant role in the design and implementation of these processes, and are able to provide substantive input to policy and programming on peace and security in Burma.

- Ensure that women’s rights are reflected in all political processes as Burma undergoes political transition. Women should be included as technical advisors, civil society advocates, gender advisors to mediators, and should be substantively represented on negotiation teams.

To the Burmese Government

- Ensure Burma is in full compliance with its obligations under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). The National Strategic Plan for the Advancement of Women 2013-2022, formulated by the previous government, should be amended to be in line with CEDAW and other international human rights conventions, and should be modified to include women’s rights concerns in settings of insecurity and conflict.

- Promptly enact the Law on Protection and Prevention of Violence Against Women without the adoption of proposed amendments that do not meet international human rights standards. The law, as adopted, should include a broad definition of rape.

- Ratify, implement, and abide by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

- Reconstitute the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission in line with the Paris Principles on national human rights institutions, including ensuring a diverse composition that includes representatives of civil society and women generally. Its activities should be gender-sensitive, and be able to fully address women’s rights issues.

- Take all necessary steps to ensure full compliance with the laws of war and international human rights standards, including gender-based crimes. Hold accountable members of the Tatmadaw responsible for serious violations of the laws of war, regardless of rank. Ensure that affected civilians and nongovernmental organizations have safe and effective avenues to bring violations to the government’s attention.

- Hold regular parliamentary hearings on abuses by all parties to Burma’s conflicts, publish reports of those hearings, and facilitate the participation of civil society organizations, including women’s rights groups, in such hearings.

- Ensure that any repatriation of internally displaced persons and refugees takes place in full compliance with international standards, including the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement and international standards on refugees. Any returns of internally displaced persons or refugees must be conducted voluntarily, in safety and dignity, and with full oversight from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and other agencies, and in full consultation and planning with refugee rights representatives and community leaders, including those representing women and girls.

To Ethnic Armed Groups

- Support the full participation of women in all decision-making regarding political transitions, decision-making regarding policy platforms of ethnic armed groups, and women’s participation on all negotiation teams, including ceasefire negotiations and on ceasefire monitoring teams.

- Work with women’s rights organizations to establish a set of principles and criteria on women’s rights for their respective negotiation platforms. These could include specific stances on women’s rights in ceasefires, political power-sharing, disarmament and demobilization, and resource allocation.

- Take all necessary steps to ensure full compliance with the laws of war and international human rights standards, including gender-based crimes, and appropriately hold accountable those responsible for serious violations.

To International Donors, Governments, and the United Nations

- Publicly and privately promote to all parties to negotiations the need for full and substantive participation by women in all peace negotiations and in all aspects of Burma’s political transition.

- Provide sustainable and effective support for women’s rights organizations and other independent actors supporting women’s participation in the peace processes and political transition.

[1] “Extracts from the nationwide ceasefire agreement,” Myanmar Times, October 15, 2015, http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/national-news/17022-extracts-from-the-nationwide-ceasefire-agreement.html (accessed August 5, 2016).

[2] Nan Lwin Hnin Pwint, “‘21st Century Panglong Conference’ Set for Late July,” The Irrawaddy, May 20, 2016 http://www.irrawaddy.com/burma/21st-century-panglong-conference-set-late-july.html (accessed August 5, 2016); Matthew Walton, “Ethnicity, Conflict and History in Burma: The Myths of Panglong,” Asia Survey, vol. 48, 6 (2008), pp. 889-910.

[3] Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), adopted December 18, 1979, G.A. res. 34/180, 34 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 46) at 193, U.N. Doc. A/34/46, entered into force September 3, 1981, arts. 4, 7, and 8. Burma ratified CEDAW in 1997. CEDAW General recommendation No. 30 on women in conflict prevention, conflict and post-conflict situations, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, CEDAW/C/GC/30, (2013), http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CEDAW/GComments/CEDAW.C.CG.30.pdf (accessed August 5, 2016); United Nations Security Council, Resolution 1325 (2000), S/RES/1325 (2000) http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/1325(2000) (accessed August 5, 2016); United Nations Security Council, Resolution 1820 (2008), S/RES/1820 (2008), http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/1820(2008) (accessed August 5, 2016); United Nations Security Council, Resolution 1888 (2009), S/RES/1888 (2009), http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/1888(2009) (accessed August 5, 2016); United Nations Security Council, Resolution 1889 (2009), S/RES/1889 (2009), http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/1889(2009) (accessed August 5, 2016); United Nations Security Council, Resolution 1960 (2010), S/RES/1960 (2010), http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/1960(2010) (accessed August 5, 2016); United Nations Security Council, Resolution 2106 (2013), S/RES/2106 (2013), http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/2106(2013) (accessed August 5, 2016); United Nations Security Council, Resolution 2122 (2013), S/RES/2122 (2013), http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/2122(2013) (accessed August 5, 2016); United Nations Security Council, Resolution 2242 (2015), S/RES/2242 (2015), http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/2242(2015) (accessed August 5, 2016).

[4] Sarah Margon (Human Rights Watch), “Aung San Suu Kyi Must Focus on Ending Burma’s Civil War,” commentary, Foreign Policy, July 11, 2016, http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/07/11/aung-san-suu-kyi-must-focus-on-ending-burmas-civil-war/ (accessed August 5, 2016). See also, Human Rights Watch, “Burma: Q & A on an International Commission of Inquiry,” March 24, 2011, https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/03/24/burma-q-international-commission-inquiry; Human Rights Watch, “They Came and Destroyed Our Village Again": The Plight of Internally Displaced Persons in Karen State, June 2005, https://www.hrw.org/report/2005/06/09/they-came-and-destroyed-our-village-again/plight-internally-displaced-persons.

[5] Letter from Human Rights Watch to President U Htin Kyaw, “Human Rights Priorities for the New Government,” May 4, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/05/04/hrw-letter-president-u-htin-kyaw.

[6] Nan Tin Htwe, “Tatmadaw admits rapes but denies they are ‘institionalised,’” Myanmar Times, March 3, 2014, http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/national-news/9742-tatmadaw-admits-rapes-but-denies-they-are-institionalised.html (accessed August 5, 2016).

[7] See for example, Women’s League of Burma, “‘If they had hope, they would speak’ - The ongoing use of state-sponsored sexual violence in Burma's ethnic communities,” November 2014, http://womenofburma.org/if-they-had-hope-they-would-speak/ (accessed August 5, 2016).

[8] “The Ministry of Defence informed the Special Rapporteur that 61 members of the military were prosecuted for sexual and gender-based violence from 2011 to 2015; of these, 31 were tried under court martial. According to information from the Government, families are sometimes invited to witness trials in military courts; however, proceedings remain opaque and victims are frequently unaware of whether action has been taken against perpetrators.” Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, A/HRC/31/71, para. 40, March 18, 2016, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session31/Pages/ListReports.aspx (accessed August 5, 2016).

[9] Letter from Human Rights Watch to President U Htin Kyaw, “Human Rights Priorities for the New Government,” May 4, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/05/04/hrw-letter-president-u-htin-kyaw.

[10] “US urges Burma to investigate deaths of two female teachers,” Associated Press, January 22, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/22/us-burma-investigate-deaths-teachers (accessed August 5, 2016). Reports were published about an arrest in the case, but there has not been public information about the results of any trial. “Thousands gather to farewell slain teachers,” Myanmar Times, January 23, 2015, http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/national-news/12879-thousands-gather-to-farewell-slain-teachers.html (accessed August 5, 2016); “Impunity for Sexual Violence in Burma’s Kachin Conflict,” Human Rights Watch news dispatch, January 21, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/01/21/dispatches-impunity-sexual-violence-burmas-kachin-conflict.

[11] “Local army commander to be questioned over Kachin teachers’ murder,” Mizzima, May 21, 2016, http://mizzima.com/news-domestic/local-army-commander-be-questioned-over-kachin-teachers%E2%80%99-murder (accessed August 5, 2016). See also, Ye Mon, “Human rights commission urges action in investigation of Kachin teachers’ murder,” Myanmar Times, July 27, 2016, http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/national-news/21585-human-rights-commission-urges-action-in-investigation-of-kachin-teachers-murder.html (accessed August 5, 2016).

[12] Report of the Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence, U.N. Doc. S/2016/361, April 20, 2016, http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2016/361 (accessed August 5, 2016).

[13] Letter from Human Rights Watch to President U Htin Kyaw, “Human Rights Priorities for the New Government,” May 4, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/05/04/hrw-letter-president-u-htin-kyaw.

[14] United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), “‘Women and Girls First’: Donors visit to Northern Shan on Joint Mission,” May 27, 2016, http://myanmar.unfpa.org/news/%E2%80%9Cwomen-and-girls-first%E2%80%9D-donors-visit-northern-shan-joint-mission (accessed August 5, 2016).

[15] Fiona MacGregor and Thu Thu Aung, “Women guardians protect deserted villages in northern Shan State,” Myanmar Times, April 6, 2016, http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/in-depth/19852-women-guardians-protect-deserted-villages-in-northern-shan-state.html (accessed August 5, 2016).

[16] “Tea break advocacy” was a term used by Burmese activists in meetings with Human Rights Watch to indicate the relegation of women’s advocacy to tea and coffee breaks outside of the main negotiation forums. Regarding women combatants, see Michelle Barsa, Olivia Holt-Ivry, and Allison Muehlenbeck, Inclusive Security, “Inclusive Ceasefires: Women, gender, and a sustainable end to violence,” undated, https://www.inclusivesecurity.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Inclusive-Ceasefires-ISA-paper-Final-3.10.2016.pdf (accessed August 5, 2016).

[17] Human Rights Watch interview with MP Ms. Ja Seng Hkawn, Myitkinya, Kachin State, May 16, 2016.

[18] See Jenny Hedström, “Myanmar” in Women in Conflict and Peace, International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2015, http://www.idea.int/publications/women-in-conflict-and-peace/upload/Women-in-Conflict-and-Peace-myanmar.pdf (accessed August 5, 2016). Hedström also writes, “The erasure of women’s experiences and knowledge from the public agenda has denied Kachin women the opportunity to define and address their own concerns and needs. As argued by D’Costa (2006: 131), this does not appear to be an oversight but rather a deliberate attempt by dominant groups to set the agenda by controlling the agency and voice of women from ethnic and religious-minority communities.” Ibid.

[19] Jenny Hedström, “Myanmar” in Women in Conflict and Peace, International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2015, http://www.idea.int/publications/women-in-conflict-and-peace/upload/Women-in-Conflict-and-Peace-myanmar.pdf (accessed August 5, 2016).

[20] Kate Hodal, “Burmese army recruits female soldiers as it struggles to tackle rebel groups,” The Guardian, October 16, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/16/burmese-army-recruits-female-soliders-rebels (accessed August 5, 2016).

[21] Kyaw Thu and Myo Thant Khine, “Myanmar Military’s First Women Representatives Join Parliament,” Radio Free Asia, January 14, 2014, http://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/women-01142014143827.html (accessed August 5, 2016).

[22] Cherry Thein, “Anger as women kept ‘in the kitchen’ during peace process,” Myanmar Times, September 23, 2015, http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/national-news/16630-anger-as-women-kept-in-the-kitchen-during-peace-process.html (accessed August 5, 2016).

[23] Human Rights Watch interview with Women’s Initiatives Network for Peace: WIN-Peace, Rangoon, May 18, 2016.

[24] Human Rights Watch meeting with female MP Ms. Ja Seng Hkawn, Myitkinya, Kachin State, May 16, 2016.

[25] Mercy Corps, “Building a Robust Civilian Ceasefire Monitoring Mechanism in Myanmar: Challenges, Successes and Lessons Learned,” Working Paper, May 2016, http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Working_Paper_Building_a_Robust_Civilian_Ceasefire_Monitoring_Mercy_Corps_May2016.pdf (accessed August 5, 2016).

[26] International Crisis Group, “Myanmar’s Peace Process: A Nationwide Ceasefire Remains Elusive,” Crisis Group Asia Briefing N°146, Yangon/Brussels, September 16, 2015, http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/asia/south-east-asia/burma-myanmar/b146-myanmar-s-peace-process-a-nationwide-ceasefire-remains-elusive.pdf (accessed August 5, 2016). Ye Mon, “KIO accuses Tatmadaw of trying to force a ceasefire,” Myanmar Times, October 2, 2015, http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/national-news/16791-kio-accuses-tatmadaw-of-trying-to-force-a-ceasefire.html (accessed August 5, 2016).

[27] Alliance for Gender Inclusion in the Peace Process (AGIPP), “Women, Peace and Security Policymaking in Myanmar,” December 2015, http://agipp.org/sites/agipp.org/files/agipp_policy_brief_1_eng.pdf (accessed August 5, 2016).

[28] “National Reconciliation and Peace Center Formed,” Republic of the Union of Myanmar, President’s Office, Order No. 50/2016, July 11, 2016, hereinafter “President’s Office Order No. 50/2016,” http://www.moi.gov.mm/moi:eng/?q=announcement/12/07/2016/id-7666 (accessed August 5, 2016).

[29] Human Rights Watch interview with female MP Ms. Ja Seng Hkawn, Myitkinya, Kachin State, May 16, 2016.

[30] Human Rights Watch interview with Soe Soe New, Women’s League of Burma, Rangoon, May 18, 2016.

[31] Human Rights Watch group interview with Kachin Independence Organization Technical Assistance Team, Myitkyina, Kachin State, May 16, 2016.

[32] Gender Equality Network and Global Justice Center, “Shadow Report on Myanmar for the 64th Session of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women,” July 2016, http://globaljusticecenter.net/documents/CEDAWFactSheetJuly2016.pdf (accessed August 5, 2016). See also, Alliance for Gender Inclusion in the Peace Process (AGIPP), “Women, Peace and Security Policymaking in Myanmar” and President’s Office Order No. 50/2016.

[33] Nyein Nyein, “Calls for More Women in Peace Process on European Study Tour,” The Irrawaddy, May 2, 2016, http://www.irrawaddy.com/burma/calls-for-more-women-in-peace-process-on-european-study-tour.html (accessed August 5, 2016).

[34] See the United Kingdom international development funding, https://www.gov.uk/international-development-funding/myanmar-peace-support-fund (accessed August 5, 2016). The Peacebuilding Support Fund mandatory criteria for funding includes, “Criteria 5) Inclusive of women's interests, the project must address the needs and interests of women, for instance by strengthening women’s participation in the peace process or initiatives to reduce inter-communal violence, or by increasing the actual and perceived safety of women and girls’ who have been affected by conflict (particularly IDPs [internally displaced persons], refugees and those in ceasefire areas).” See “Peace Support Fund Criteria,” www.peacesupportfund.org (accessed July 26, 2016).

[35] Human Rights Watch meeting with Kachin Women’s Association – Thailand (KWAT), Myitkyina, Kachin State, May 16, 2016.

[36] Human Rights Watch group interview with Kachin Independence Organization Technical Assistance Team, Myitkyina, Kachin State, May 16, 2016.

[37] Human Rights Watch interview with Soe Soe New, Women’s League of Burma, Rangoon, May 18, 2016.

[38] Fiona Macgregor, “Woman MPs up, but hluttaw still 90% male,” Myanmar Times, December, 1, 2015, http://www.mmtimes.com/index.php/national-news/17910-woman-mps-up-but-hluttaw-still-90-male.html (accessed August 5, 2016).

[39] Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, Forty-second session 20 October to 7 November 2008 Concluding observations of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, CEDAW/C/MMR/CO/3, 7 November 2008, http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs5/CEDAW-C-MMR-CO-3.pdf (accessed August 5, 2016); Women’s League Of Burma, “Shadow Report On Burma For The 64th Session Of The Committee On The Elimination Of Discrimination Against Women”, July 2016 http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CEDAW/Shared%20Documents/MMR/INT_CEDAW_NGO_MMR_24233_E.pdf (accessed August 5, 2016).

[40] The Declaration was launched at a summit in London in 2014. Governments that sign the Declaration pledge to: “do more to raise awareness of these crimes, to challenge the impunity that exists and to hold perpetrators to account, to provide better support to victims, and to support both national and international efforts to build the capacity to prevent and respond to sexual violence in conflict.” “A Declaration of Commitment To End Sexual Violence In Conflict,” undated, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/274724/A_DECLARATION_OF_COMMITMENT_TO_END_SEXUAL_VIOLENCE_IN_CONFLICT.pdf (accessed August 5, 2016).

[41] Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, A/HRC/31/71, para. 40, March 18, 2016, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session31/Pages/ListReports.aspx (accessed August 5, 2016). See also, Women’s League of Burma, "‘If they had hope, they would speak’ - The ongoing use of state-sponsored sexual violence in Burma's ethnic communities.”

[42] Report of the Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence, U.N. Doc. S/2015/203, March 23, 2015, http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2015/203 (accessed August 5, 2016).

[43] Article 376 of the Penal Code criminalizes rape and provides minimum and maximum penalties, but activists say the maximum penalty for the crime of rape is almost always reduced. For further analysis see, “Rape victims struggle to find justice in Myanmar,” Myanmar Now, February 2, 2016, http://www.myanmar-now.org/news/i/?id=aa0320cc-cb14-4750-ad79-25d085739969 (accessed August 5, 2016).

[44] Report of the Secretary-General on conflict-related sexual violence, S/2016/361, April 20, 2016, http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2016/361 (accessed August 5, 2016).

[45] The current definition of rape in Burma is both restricted to too few cases and unclear in its definition of penetration. As argued by the Gender Equality Network, “The definition of rape in the Penal Code would be improved if it encompassed a variety of non‐consenting acts of sexual violence, and not just the traditional definition of sexual intercourse.” See Gender Equality Network, “Myanmar Laws and CEDAW: The Case for Anti‐Violence Against Women Laws,” Briefing paper, January 2013, http://www.genmyanmar.org/publications/Myanmar%20Law%20and%20CEDAW%20Book%20(English%20).pdf (accessed August 5, 2016).

[46] “Burma Launches National Plan to Empower Women,” The Irrawaddy, October 7, 2013, http://www.irrawaddy.com/burma/burma-launches-national-plan-empower-women.html (accessed August 5, 2016).

[47] These and other laws enacted at the time were strongly criticized as being discriminatory against Muslims and women by UN special procedures, the EU, and the US. “Burma: Discriminatory Laws Could Stoke Communal Tensions,” Human Rights Watch news release, August 23, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/08/23/burma-discriminatory-laws-could-stoke-communal-tensions. See also, “Burma: Reject Discriminatory Marriage Bill - Imperils Right to Marry Freely, Fuels Anti-Muslim Groups,” Human Rights Watch release, July 9, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/07/09/burma-reject-discriminatory-marriage-bill.