It is now widely acknowledged that an armed conflict is taking place across Syria between government forces (including militias) and organised armed opposition groups. This means the laws of war (also known as international humanitarian law, or IHL) apply and bind all sides, and violations may amount to war crimes.

These detailed laws have been in force for decades, so we are a long way from the days when it could be said that in times of war the law falls silent. But the basic principles of the laws of war are still surprisingly little understood. The words “war criminal” seem to be mostly used as a term of derision, rather than a statement of fact, let alone a requirement to prosecute. Therefore it is vital to understand the basic principles of IHL when considering what is going on in Syria today.

The most basic principle of all is that all parties fighting in the conflict must distinguish between combatants and civilians, and take “all feasible precautions” at all times to protect civilians and civilian property. Civilians, and civilian objects – eg homes, schools, hospitals – may never be the object of attack, so they can never be specifically targeted.

This does not mean that every civilian death is a violation of IHL. The parties can target military objectives, including enemy fighters and weapons, but also civilian buildings and bridges being used by enemy forces. Civilians who are taking “a direct part in hostilities” can be attacked for the period they have joined in the fight, including civilian leaders commanding forces. At the same time, fighters who have been taken out of combat, such as through being seriously wounded or captured, or who have surrendered, are entitled to protection from attack.

International law does not just prohibit targeting civilians. It prohibits indiscriminate attacks, those that do not or cannot distinguish between military targets and civilians. This can be when attacks are not directed at a military objective or when the weapons or their particular use are inherently indiscriminate, as in many cases of shelling of populated areas. Even if the attackers are targeting a clear military objective, they may not mount attacks where the anticipated loss of civilian life or damage to civilian property is disproportionate to the expected military advantage to be gained.

Defenders as well as attackers are required to take all feasible steps to protect civilians. This means all sides must avoid deploying military targets such as fighters or weapons in or near densely populated areas, and they must try to remove civilians from areas of military operations.

An example of the requirement to always distinguish between military targets and civilian objects would be attacks on a television station. The station could only be directly attacked if it were being used for direct military purposes, such as relaying military orders. Simply broadcasting pro-government or opposition propaganda is not a justification for attack. On the other hand, if one side were to send its fighters into the TV station, the other side could target those fighters so long as the attack did not violate the rules on indiscriminate or disproportionate attacks.

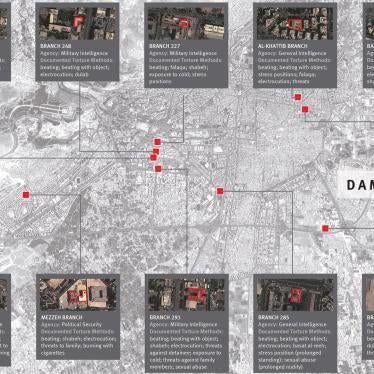

A key area in which many abuses take place in conflict is in the treatment of detainees, and so application of the law is critically needed here. Both IHL and international human rights law – which continues to apply at all times – protect all detainees, strictly prohibiting executions, torture and other abuse. The most fundamental principles of human rights law apply even during genuine emergencies, including the requirements that all detention is subject to judicial review and that only courts of law may try and convict people.

But law needs enforcement, which is where prosecuting war crimes is critical. War crimes are essentially serious violations of IHL committed by individuals with criminal intent. They are committed not just by the fighters who carry them out, but those who order them, and those who assist, aid or abet those fighters. The Sierra Leone special court's conviction of the former Liberian president Charles Taylor shows that those who give assistance to forces knowing they are committing war crimes may be responsible themselves for aiding and abetting those crimes. Commanders, military or civilian, may also be criminally responsible for war crimes committed by their subordinates that they should have known about and that they failed to prevent or prosecute.

While prosecuting Syrians implicated in war crimes should in principle take place in Syria, this could be done in the many countries that accept universal jurisdiction for these crimes. In reality, at this point, the one court that could prosecute war crimes by all sides – as well as the well-documented crimes against humanity committed by government forces during the past year – is the international criminal court.

But that court will only realistically have jurisdiction in Syria if the UN security council refers the situation in Syria to the court, which means a much more united and concerted push than we have seen to date by European countries and others to obtain such a resolution. The real prospect of being pursued around the world for war crimes will do more than anything else to persuade commanders to ensure that their forces comply with the law and that civilians are spared the worst of the conflict.

Clive Baldwin is senior legal advisor at Human Rights Watch