1. What is the Ben Ali trial all about?

4. What are the shortcomings of the trial?

5. Are there other trials in connection with the December 2010 uprising?

7. Why are the Ben Ali trials taking place before military tribunals?

8. Can military courts guarantee fair trials and effective access to justice?

9. May victims participate in the proceedings?

10. What were the main stages of the Le Kef Trial? How many hearings have taken place?

11. What evidence has been produced against Ben Ali and his co-defendants?

12. Did the trial respect the rights of the defendants?

13. Why should military courts’ jurisdiction be restricted to purely military offenses?

14. How does Human Rights Watch view the death penalty?

15. What is the public perception in Tunisia of the trials?

16. What other proceedings, charges, and sentences have there been against Ben Ali?

17. What are the forms of redress available to victims?

18. Why is Ben Ali being tried in absentia? How does Human Rights Watch view trials in absentia?

19. Are there other forms of truth-seeking for the crimes committed during the Ben Ali regime?

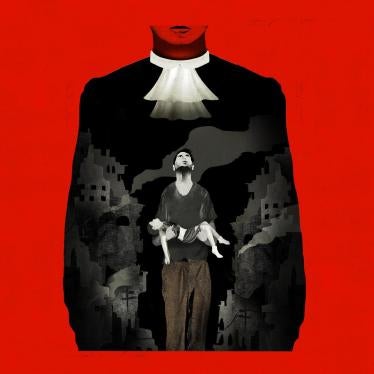

1. What is the Ben Ali trial all about?

The trial of former President Zine el Abidine Ben Ali, two of his former interior ministers, four directors general of the security forces, and 16 other high commanders and lower-ranking officers of the security forces is based on charges of murder and attempted murder of protesters during Tunisia’s popular uprising. The trial covers events between December 17, 2010, and January 14, 2011, when Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia. The trial opened on November 28, 2011 before the Permanent Military Tribunal in the governorate of Le Kef and covers killings in the governorates of Le Kef, Jendouba, Béja, Siliana, Kasserine, and Kairouan. It is widely referred to as the “Le Kef Trial.”

The popular protests that led to Ben Ali’s ouster left 132 people dead and 1,452 injured during the dates the trial covers, according to the final report issued on May 4, 2012, by the “National Fact Finding Commission on Abuses Committed from December 17, 2010 to the End of its Mandate,” created by the first transitional government. Some of the deadliest incidents took place on January 8, 9, and 12 in the towns of Kasserine, Tala, and Regueb, leaving 23 people dead and more than 600 injured. Most casualties resulted from live gunfire by security forces.

2. Who are the defendants?

The accused are former President Zine el Abidine Ben Ali; former interior ministers Rafik Hadj Kacem and Ahmed Friâa; Adel Tiouiri, the former director general of the National Security Forces; Jalel Boudriga, the former director general of the Anti-Riot Police (Brigades de l’Ordre Public); Ali Seriati, the former director general of the Presidential Guard; and Lotfi Zouaoui, the former director general of the Public Security Forces. Fourteen other commanders and lower-ranking officers are also charged. Of the 22 defendants, nine have been in custody since April 2011, twelve are provisionally free, and one – Ben Ali – is at large.

3. What are the charges?

Ben Ali, his two interior ministers, and the four security forces directors are charged with complicity in willful murder and attempted murder on the basis of article 32 of the penal code. This defines complicity as facilitating the commission of a crime by aiding, abetting, assisting, or giving instructions to commit a crime, or conspiring with others to fulfill a criminal purpose. Others are charged with premeditated murder or attempted murder under articles 201, 202, and 59 of the penal code.

Article 201 provides the death penalty for premeditated murder, though article 53 gives judges the discretion to apply lesser sentences, depending on the circumstances of the case. Article 33 requires the application of the same penalties to both the principal perpetrators and accomplices, meaning that those convicted under article 32 for complicity in premeditated murder could face the death penalty.

4. What are the shortcomings of the trial?

While Human Rights Watch did not witness serious violations of the right to a fair trial, the absence of a “command responsibility charge” under Tunisian law hampered the ability of the authorities to prosecute defendants effectively for acts that would amount to crimes in international law. In addition, the promotion of several defendants after their indictments for serious crimes suggests that elements within the security forces remained opposed to accountability.

Inadequate criminal laws on command responsibility

The Le Kef Trial is based on the alleged responsibility of the defendants for the conduct of security forces under their command, but Tunisian law is not well-equipped to address command or superior responsibility. It states that a person can be held criminally accountable only for the direct commission of a crime or complicity, in accordance with article 32 of the penal code. Such forms of liability do not cover what is known as “command or superior responsibility,” under international law, which imputes liability to commanders or civilian superiors for crimes committed by subordinate members of armed forces or other persons under their control.

Under this principle, a commander can be held criminally responsible even if he or she did not order the crimes committed if there is evidence to prove three conditions: that an effective superior-subordinate relationship exists; that the commander knew or had reason to know that his subordinate was committing a crime; and that the commander failed to prevent or punish such acts. This form of liability encompasses responsibility for failure to act. However, Tunisian governments have failed to incorporate this principle into Tunisian law, which requires evidence of a positive act to establish complicity in the commission of a crime.

The case of Seriati, one of the defendants in the Le Kef Trial, illustrates the difficulties of the tribunal’s sole reliance on the crime of “complicity” in its judgment. Seriati was the director general of the Presidential Guard from September 1, 2001, to January 14, 2011, when the authorities arrested him after Ben Ali fled the country. As director general, Seriati presumably had effective control over the presidential guard, consisting of 2,500 special security forces. The investigative judge did not present evidence indicating that the forces under Seriati’s command participated in the repression of the protesters. In addition, defense lawyers introduced evidence from an Interior Ministry investigation, which concluded that no ammunition assigned to the presidential guard was used to quell the protests. This was not contested by the prosecution.

However, the prosecution said he should be found guilty of complicity in premeditated killing under article 59. The prosecution contended that he bore responsibility because he participated in the crisis cell meetings from January 8 to 10, as a member of the decision-making circle that controlled the response to the uprising. Although the judge did not find any evidence of shoot-to-kill orders, or even orders to use live ammunition on protesters, he concluded that Seriati was responsible based on witness testimony that he was very influential among security forces. The theory of liability applied in this case resembles guilt by association, which does not appear to meet the standard of individual criminal responsibility.

The defense lawyers also contended that the prosecution provided no evidence that the defendants who held high command positions either gave orders to quell protests by using deadly force, or were in any other way responsible for the killing of protesters. They argued that the prosecution was imputing guilt to the defendants merely on the basis of their political responsibility, without proving the elements of complicity in the commission of the crimes. They contended that the killings were the result of individual acts by police agents who ran amok during a period of violent protests. In addition, some of the defense lawyers said that they produced evidence showing that the defendants they represented gave orders to police to exercise maximum restraint in facing protesters that the court did not duly consider.

Promotion of some accused to higher positions

Transitional government ministers promoted some of the defendants in the Le Kef Trial to higher positions in state security, despite the pending charges against them, raising concern about the willingness of the interim authorities to ensure accountability.

For example, the second transitional government – between March and October 2011 – in March appointed one of the accused, Moncef Krifa, who had been regional director of Anti-Riot Police in Kasserine (Brigades de l’ordre Public, BOP), to be director of the Presidential Guard.

Likewise, after his indictment, the same government promoted Moncef Laajimi, a defendant who had been head of the Anti-Riot Police in Tala, to be director general of the Anti-Riot Police. On January 10, 2012, the new interior minister, Ali Laariadh, removed Laajimi from his position. However, under pressure from the Anti-Riot Police union, who threatened a general strike, he later retracted his decision and appointed Laajimi deputy chief of cabinet at the Interior Ministry.

5. Are there other trials in connection with the December 2010 uprising?

There are two group trials. In the other, the “Tunis Trial,” before the Permanent Military Tribunal of Tunis, 43 people are accused of murdering protesters in the governorates of Tunis, Ariana, al-Manouba, Ben Arous, Bizerte, Nabeul, Zaghouan, Sousse, and Monastir. As in the Le Kef Trial, defendants in the Tunis Trial include Ben Ali, his two former interior ministers, and the four former directors general of security forces. The others charged in the Tunis Trial are Mohamed el Arbi Krimi, director of the Central Operations Room at the Interior Ministry; Ali Ben Mansour, the inspector general of security forces, and Rachid Ben Abid, the director of Special Services, as well as other high commanders and lower-ranking officers.

In addition, there is an ongoing trial before the Permanent Military Tribunal of Tunis against four members of the security forces accused of killing six people when police opened fire on members of neighborhood defense committees on January 15, 2011 in Ouardanine, a town 120 kilometers south of Tunis.

Finally, on April 30, 2012, the Permanent Military Tribunal of Sfax sentenced two policemen, Omran Abdelali and Mohamed Said Khlouda, to 20 years in prison and an 80,000 dinar fine (US$49,230) for killing Slim Hadhri, who was shot dead while participating in a demonstration on January 14, 2011 in Sfax, a city 270 kilometers south of Tunis.

6. What kind of accountability for human rights violations will the trials of Ben Ali and his co-defendants establish?

To the extent that they are seen to have been transparent and fair, the trials for the crimes committed during the uprising are an opportunity to break with the impunity for security forces for widespread human rights violations during the 23 years of the Ben Ali presidency. It also helps to establish a record of the events between December 17, 2010 and January 14, 2011, and to assign responsibility for the deaths and injuries of protesters during that period, including the responsibility of commanders who supervised the security forces that used lethal force.

However, the Le Kef and the Tunis trials are limited in their temporal scope. The state has an obligation to investigate and ensure accountability for the grave human rights abuses by the government during the 23-year-long Ben Ali presidency, not just during the month- long protests that brought it to an end. These abuses included torture and prolonged arbitrary imprisonment for nonviolent political and speech offenses.

7. Why are the Ben Ali trials taking place before military tribunals?

Under article 22 of Law 70 of August 1982 regulating the Basic Status of Internal Security Forces, military tribunals have jurisdiction over all crimes alleged to have been committed by members of the security forces, regardless of who the victims are or the capacity in which the crimes were allegedly committed. Initially, victims of the government’s violence during the popular uprising filed complaints in civilian courts in their areas of residence. The first to open an investigation, on February 24, 2011, was the prosecutor for the first instance courtin Kasserine, a town 218 kilometers southwest of Tunis. However, investigative judges in the first instance tribunals of Kasserine, Kairouan, and Le Kef transferred the case files to the military justice system.

Article 22 states that “cases involving agents of the internal security forces for their conduct during the exercise of their duty and linked to internal or external state security, or to the protection of public order […] during public meetings, processions, marches, demonstrations, and gatherings, must be transferred to the competent military courts.”

8. Can military courts guarantee fair trials and effective access to justice?

The transitional government’s reforms of the military justice system improve guarantees for fair trials and effective access of victims to justice. They give victims the opportunity to file complaints, make claims for reparation, and be represented before the military courts. But the reforms fall short of guaranteeing the independence of military courts from the executive branch.

Tunisia’s code of military justice was promulgated on January 10, 1957. After the fall of the Ben Ali government, the transitional government overhauled the military justice system and strengthened fair trial guarantees, including certain rights for defendants. Decree 69 of July 29, 2011, modifying the military justice code, and Decree 70 of July 29, 2011, relating to the organization of military courts and military judges, form the new legal framework applicable to the military justice system. The new laws introduced three principal reforms:

- Reinforcement of the independence of the military justice system from the executive branch of government by abolishing the general prosecutor’s obligation to inform the defense minister before penal proceedings begin and to get the defense minister’s permission to proceed; and ending the defense minister’s power to suspend the execution of military court sentences.

- Creation of a military appeals court with jurisdiction to review all criminal verdicts by a first degree military tribunal. In addition, criminal appellate divisions consisting of one military judge and two judges from civilian courts must now review and confirm indictments filed by military investigative judges.

- A requirement that military courts apply the ordinary code of criminal procedure at all stages of the proceedings. The reforms also affirm the mixed composition of military courts to include both military judges and civilian judges. Judges from civilian courts serve as presidents of the military appeals court and presidents of the permanent military first instance courts of Tunis, Le Kef, and Sfax in times of peace.

Despite these reforms, concerns remain about the independence of the military justice system. Although the law states that military judges are independent from the military hierarchy in the exercise of their duties, they are still formally dependent on the Defense Ministry through the High Council of Military Judges, headed by the defense minister, which oversees the appointment, advancement, discipline, and dismissal of military judges. In addition, the Tunisian president appoints civilian judges to serve in military courts by decree, pursuant to the recommendation of the ministers of justice and defense.

As a result, the military justice system does not have independence in accordance with international standards. Principle 13 of the Draft Principles Governing the Administration of Justice through Military Tribunals, elaborated in 2006 by the United Nations Human Rights Commission, the predecessor to the UN Human Rights Council, requires that “military judges should have a status guaranteeing their independence and impartiality, in particular vis-à-vis the military hierarchy.” The same principle further states, “The statutory independence of judges vis-à-vis the military hierarchy must be strictly protected, avoiding any direct or indirect subordination, whether in the organization and operation of the system of justice itself or in terms of career development for military judges.”

9. May victims participate in the proceedings?

Under the newDecree 69, victims may now file claims and be represented before military courts. Article 7 of the law stipulates that the “constitution of civil parties and the launching of civil actions are allowed before military justice in conformity with the rules and procedures set up in the criminal procedure code.” The code of criminal procedure allows “all those who have personally suffered a harm as a direct result of the offense” to bring an action. In addition, victims now have the right to make claims for reparation under the criminal procedure code.

10. What were the main stages of the Le Kef Trial? How many hearings have taken place?

Following the transfer of the cases initially filed in the first degree tribunals of Kasserine, Kairouan, and Le Kef to the military judicial system, the military investigative judge of the Le Kef Military Tribunal, Faouzi Ayari, issued indictments against the 22 defendants on August 17, 2011. The criminal appellate division of the Le Kef Appeals Court reviewed the indictment and issued its confirmation of the charges on September 6, 2011. The trial started at the Le Kef Military Tribunal on November 28. The tribunal has held 10 hearings, during which it examined evidence and interrogated the defendants and witnesses. Oral pleadings started on May 21, with pleadings and arguments of the lawyers for the victims, the public prosecutor, and defense lawyers.

11. What evidence has been produced against Ben Ali and his co-defendants?

The indictment largely consists of the testimony of hundreds of witnesses saying that police either shot at them or that they saw them shooting at others who were participating in demonstrations. In most of the cases, the witnesses were not able to identify the people who actually did the shooting; the witnesses said they saw both local police and other security forces working to quell the protests. In a few cases, witnesses said they saw the person who opened fire and identified the person by name. It appears from what was stated in court and from the case files that the evidence does not contain detailed ballistic analysis and has few forensic examinations.

The investigative judge in the trial interrogated several police officers who were present during the events. None of them admitted to having received orders to use live ammunition and instead they said they fired on protesters in self-defense. To analyze the orders given to police forces to quell the protests, the investigative judge also turned to the records of the Interior Ministry’s central operations unit from December 2010 and January 2011. The role of this unit was to monitor security developments in the country, inform the interior minister and the directors of security forces, and transmit orders to security units. All of the telephone conversations from or to the unit were automatically recorded on the hard drive of the central operations unit.

The investigative judge said that he did not find orders to use live ammunition to quell protesters in these recordings. However, he noted that the directors of the security forces could use cell phones to transmit orders to regional and divisional police units without any recording of the call in the central unit recording system.

In the absence of direct evidence of orders to kill or the identification of the exact person involved in each incident involving death or injury of a protester, the investigative judge relied on inferential reasoning and circumstantial evidence to prove the existence of a plan to murder protesters by the highest officials of the government.

12. Did the trial respect the rights of the defendants?

The courts appeared generally to respect the rights of the defendants to a fair trial. Defendants had access to lawyers of their own choosing and the opportunity to prepare an adequate defense with access to the evidence presented against them, and the opportunity to cross examine witnesses and introduce exonerating evidence in support of their defense.

All international and regional human rights instruments require governments to provide the right to a fair hearing before a legally constituted competent, independent, and impartial judicial body. Among other things, this right includes: adequate opportunity to prepare a case, present arguments and evidence, and challenge or respond to opposing arguments or evidence; the right to consult and be represented by a legal representative; and the right to a trial without undue delay and to an appeal to a higher judicial body.

During the Le Kef Trial, all of the accused had the right to choose their own legal representatives. Defense counsel confirmed that they had access to the case files and were able to obtain all of the documents in these files, including the indictment, the testimony of victims and witnesses, and the other evidence used during the proceedings. They were also able to perform cross examinations, to call witnesses, and to introduce evidence.

However, defense lawyers said that at times the court refused certain requests that they considered important for their defense strategy. For example, the court refused their request for a list of the cellular phone calls their clients made between December 24, 2010, and January 14, 2011, which they needed to verify whether the defendants had communicated with their subordinates, as alleged by the prosecution. While the defense had pending requests to introduce additional exonerating evidence and for access to documents they considered important, the Le Kef Trial judges abruptly ordered closing arguments.

13. Why should military courts’ jurisdiction be restricted to purely military offenses?

Human Rights Watch strongly opposes any trials of civilians before military courts, where the proceedings do not protect due process rights or satisfy the requirements of independence and impartiality of courts of law.

Even for the trial of military or security forces, there is a crystallizing norm of international law requiring that the jurisdiction of military courts should be restricted to trying purely military offenses. As a result, Human Rights Watch encourages the use of civilian courts for all cases of human rights violations against civilians, regardless of whether the defendants are civilian or military.

The UN Human Rights Committee also urges states parties to the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment to try military personnel who are charged with human rights violations in civilian courts. In 1999 the committee wrote in its concluding observations in a report by Chile that the “wide jurisdiction of the military courts to deal with all the cases involving prosecution of military personnel ... contribute[s] to the impunity which such personnel enjoy against punishment for serious human rights violations.”

In the case Suleiman v. Sudan on May 2003, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights also affirmed that military tribunals should only “determine offences of a purely military nature committed by military staff” and “should not deal with offences which are under the purview of ordinary courts.” In addition, the principles and guidelines on the right to a fair trial and legal assistance in Africa issued by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights states, “the only purpose of Military Courts shall be to determine offences of a purely military nature committed by military personnel.”

14. How does Human Rights Watch view the death penalty?

During the final pleadings in the Le Kef Trial on May 23, 2012, the military prosecutor requested the death penalty against former president Ben Ali and harsh sentences against all of the other defendants. Human Rights Watch opposes capital punishment in all circumstances because of its inherent cruelty and irreversibility. In addition, it is a form of punishment that is plagued with arbitrariness, prejudice, and error.

15. What is the public perception in Tunisia of the trials?

The trial has been regularly covered by Tunisian media. Journalists have had access to the proceedings and extensively covered them in print, radio, and television media. Both victim representatives and defense lawyers have regularly questioned the willingness and ability of the Tunisian judiciary to pursue effective prosecutions, and these concerns have been well reported in the media and have contributed to public criticism of the trials.

The defense and victims have expressed concern about the lack of ballistic and forensic examinations that would have identified individuals who shot the demonstrators. The defense and victims have also contended that the Interior Ministry was uncooperative, for example in not providing important pieces of evidence to the tribunal, such as the register the ministry allegedly keeps of guns and ammunition available to each agent. In addition, the families of victims regularly have criticized the fact that some of the accused were released on bail and even promoted to higher positions.

16. What other proceedings, charges, and sentences have there been against Ben Ali?

The First Degree Tribunal of Tunis sentenced Ben Ali to more than 66 years in prison on charges ranging from embezzlement to drug trafficking. The First Degree Tribunal of Tunis sentenced him, together with his wife, on June 20, 2011, to 35 years in prison and $65.6 million fines for theft and unlawful possession of money and jewelry. The Permanent Military Court of Tunis also sentenced him to five years in prison for “using violence” against 17 high ranking military officers, in the case known as “Barraket Essahel,” after the town where authorities said they had uncovered a plan orchestrated by officers to topple Ben Ali and establish an Islamist regime in 1991.

17. What are the forms of redress available to victims?

In February 2011, the interim government decided to allocate 20,000 dinars (US$12,624) to families of those killed and 3,000 dinars ($1,900) to those injured during the uprising, regardless of the severity of the injury. Authorities paid compensation to 2,749 of those injured and to the families of 347 of those killed, according to official numbers. In December 2011, the interim government distributed a second installment of the same amount to the injured and the families of those killed. However, these limited reparations measures have not met the needs for ongoing medical treatment and care of victims, or provided them with adequate financial compensation for lost wages.

The Le Kef Trial and Tunis Trial will determine the material damage resulting from the use of force at the end of the trials. Article 7 of Law no. 69 of July 29, 2011 gives victims the right to make claims for reparation for the harm suffered based on the rules applicable in the ordinary criminal procedure code.

18. Why is Ben Ali being tried in absentia? How does Human Rights Watch view trials in absentia?

Ben Ali fled Tunisia to Saudi Arabia on January 14, 2011. Although there is an international arrest warrant pending against him, Tunisia has yet to press for his extradition. Since his appointment as new head of government, Hamadi Jebali has declared that the extradition of Ben Ali is not a priority of the interim authorities. On February 17, 2012, on the eve of an official visit to Saudi Arabia, Jebadi said on Radio SAWA that he would not discuss Ben Ali’s extradition with the Saudis, calling the case “minor, not a priority.”

Trying a defendant in absentia can undermine some of the defendant’s basic rights to a fair trial, including the right to be present, to be defended by counsel of the person’s choice, and to examine witnesses. International law does not favor but does not prohibit trials in absentia. National systems that maintain the practice should, at minimum, institute procedural safeguards to ensure the defendant’s basic rights. These include requirements that the defendant be notified in advance of the proceedings and that the defendant unequivocally and explicitly waive his right to be present. The defendant should also have the right to representation in his or her absence, and should be able to obtain a fresh determination on the merits of the conviction following the person’s return to the jurisdiction.

Tunisian criminal procedure law does not have specific provisions on trials in absentia. The Le Kef Tribunal did appoint a lawyer to defend Ben Ali, but the lawyer did not participate fully in the proceedings. During the final pleadings, he was present but declined to make an argument. These elements indicate that the minimum procedural safeguards for trials in absentia were not met in this case.

19. Are there other forms of truth-seeking for the crimes committed during the Ben Ali regime?

Law no. 8, dated February 18, 2011, passed shortly after Ben Ali’s ouster, created “a National Fact Finding Commission on Abuses Committed from December 17, 2010 to the End of its Mandate.” Tawfik Bouderbala, a well-known figure of Tunisian civil society and former president of the Tunisian League for Human Rights, was appointed president of the commission and selected the rest of its 14 members. Its mandate stated it would collect information and documentation on the abuses during the period through testimony of the victims or the families of those killed or injured and documents to be collected from any relevant administration or institution. The Commission issued its final report on May 4, 2012. The report contains 1,040 pages, including annexes (with a list of injured and killed).

Following the elections of the National Constituent Assembly (NCA) on October 23, 2011, the Assembly adopted the Law on the Organization of Interim Powers. Article 24 of this law states that, “the NCA will enact a basic law organizing the mechanisms and principles for transitional justice.” To date, the NCA has not adopted such a law.