It's easy to see why Iraqis overwhelmingly sought asylum in Sweden last year. The country had granted 91 percent of their asylum requests the year before. But why would the next-largest number apply in Greece, which had a zero approval rate for Iraqis? And why did relatively few Iraqis, the largest group of asylum seekers in the European Union, seek asylum in Britain, with troops on the ground in Iraq - or Germany, with Europe's largest population and strongest economy, or other EU countries?

EU asylum rules provide the answer: Many Iraqis lodged their asylum claims in Greece because they had no other choice. Because of its location, Greece is the most favorable entry point to the EU for Iraqis. And the EU system, known as Dublin II, dictates that claims are generally assessed in the first EU state a person enters.

An Iraqi Kurd from Kirkuk told me of his predicament: "I wanted to go to another country to seek asylum, but a friend told me that because they took my fingerprints, they would send me back to Athens. I have now been here a month without papers. Now I am in a hole. I can't go out. I can't stay. Every day I think I made a mistake to leave my country. I want to go back, but how can I? I would be killed if I go back. But they treat you like a dog here. I have nothing. No rights. No friends."

The Dublin system fails to consider the legitimate interest asylum seekers have in choosing where to apply and unfairly allocates the burden of processing claims to the states on the EU's external frontiers.

Left nearly alone to bear the Iraqi refugee burden in Europe, both Sweden and Greece have reacted in ways that are as unfortunate as they are predictable. Sweden has become much less generous in offering asylum. By the first trimester of 2008, it was granting only 25 percent of requests. The result? The number of Iraqi asylum applicants in Sweden fell by half in the first half of 2008.

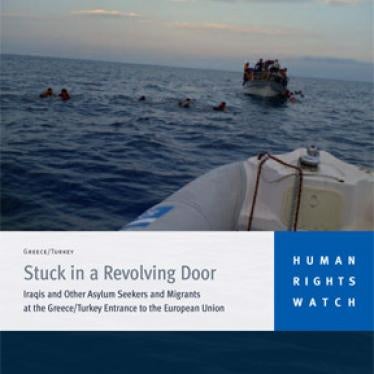

Greece has taken the approach, documented in a Human Rights Watch report to be released next week, of systematically rounding up and detaining migrants in dirty, overcrowded conditions in the border region with Turkey and forcibly and secretly expelling them to Turkey. Coast Guard officials push migrants from Greek territorial waters, sometimes puncturing inflatable boats or otherwise disabling their vessels. For those managing to gain a foothold in Greece, the authorities block access to asylum procedures and deny nearly all asylum claims.

A 34-year-old Iraqi Turkoman from Kirkuk who said that he made 10 attempts to cross into Greece before succeeding provides a typical example among the scores of interviews collected by Human Rights Watch: "One time I crossed the river into Greece and arrived in Komotini. They put us in jail for five days and then took us to the river and pushed us back. We were 60 persons. They put us in a small river boat with a motor in groups of 10. They did it in the middle of the night. It was raining hard and the Greek police started beating us to make us move more quickly. I saw one man who tried to refuse to go on the boat, and they beat him and threw him in the river. They beat us with police clubs to get us to go on the boat."

The Turkish border authorities likewise abuse migrants, detaining those pushed back by Greece in degrading conditions. These migrants have no real opportunity to seek asylum in Turkey and are often detained indefinitely. Turkey continues to return Iraqis to Iraq without giving them a genuine chance to seek protection.

As the UN High Commissioner for Refugees has urged, EU states should suspend transfers of asylum seekers back to Greece and examine their claims themselves. They should resume such transfers only when Greece meets EU standards on detention, police conduct and asylum access, and when Greece stops forcibly returning people who would face inhuman and degrading treatment in Turkey or persecution in their countries of origin.

A more equitable and better-managed approach by the EU would reduce the burden on Sweden and Greece and better protect Iraqi refugees. But the EU's failures in equitable burden-sharing do not relieve Greece of its responsibility to treat people humanely and its obligation not to return refugees and asylum seekers to a risk of degrading treatment, persecution, or worse.

Bill Frelick is the refugee policy director at Human Rights Watch and author of "Stuck in a Revolving Door: Iraqis and Other Asylum Seekers and Migrants at the Greek/Turkey Entrance to the European Union."