(Athens, November 26, 2008) - Greece systematically rounds up and detains Iraqi asylum seekers and other migrants in dirty, overcrowded conditions and forcibly and secretly expels them to Turkey, Human Rights Watch said in a report issued today. Under EU rules, most Iraqis who enter the European Union through Greece must claim asylum there.

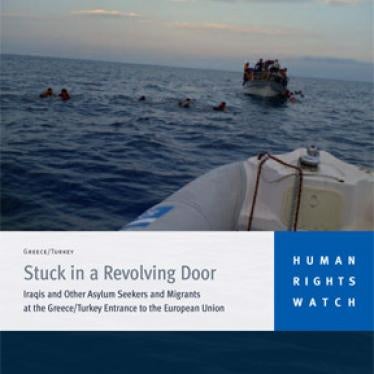

The 121-page report, "Stuck in a Revolving Door: Iraqis and Other Asylum Seekers and Migrants at the Greece/Turkey Entrance to the European Union," documents how Greek Coast Guard officials push migrants out of Greek territorial waters, sometimes puncturing inflatable boats or otherwise disabling their vessels. For those managing to gain a foothold in Greece, the authorities block access to asylum procedures and deny nearly all asylum claims.

"Greece denies protection to vulnerable people and abuses them in detention," said Bill Frelick, refugee policy director at Human Rights Watch and author of the report. "Until Greece cleans up its act, EU states shouldn't send asylum seekers back there."

The report also documents abuses of migrants by Turkish border authorities, including detaining the migrants in inhuman and degrading conditions. Migrants returned from Greece have no meaningful opportunity to seek asylum in Turkey and are often detained indefinitely. Turkey continues to return Iraqis to Iraq without giving them meaningful opportunities to seek protection.

Based on the false assumption that all EU states have the same standards and procedures for determining refugee status, the European asylum system, governed by the regulation known as Dublin II, generally holds the state of first entry responsible for examining an asylum claim.

Consequently, the Greek authorities try to prevent asylum seekers from entering the EU at the Greek border, and if they do succeed in entering, try to block their access to asylum procedures. Those who manage to lodge asylum claims are almost always denied. In 2007, out of 25,111 asylum claims, Greece granted refugee status to eight persons after the first interview, an approval rate of 0.04 percent; the approval rate at the appeals stage was 2 percent.

"The Dublin system traps asylum seekers in a revolving door," said Frelick. "They can't move onward because the Dublin II regulation normally requires asylum seekers to lodge their claims for protection in the first EU country in which they set foot, and they also can't move back home because of fear of war and persecution. They are almost never provided asylum in Greece."

An Iraqi Kurd from Kirkuk who was among the scores interviewed by Human Rights Watch, made five attempts to cross from Turkey to Greece and was beaten and summarily expelled from Greece. He was also beaten and detained by the Turkish authorities. After the Greek authorities finally registered him, they used detention to deter him from seeking asylum. "They told me that if I asked for asylum and a red card that I would need to spend more time in jail beyond 25 days, but if I didn't want asylum and a red card I could leave detention after 25 days. So, I refused the red card and after 25 days they released me. I got a white paper telling me I needed to leave the country in 30 days.

"I wanted to go to another country to seek asylum, but a friend told me that because they took my fingerprints, they would send me back to Athens. I have now been here a month without papers. Now I am in a hole. I can't go out. I can't stay. Every day, I think I made a mistake to leave my country. I want to go back, but how can I? I would be killed if I go back. But they treat you like a dog here. I have nothing. No rights. No friends."

Greek and Turkish immigration enforcement authorities seem as frustrated with the revolving door as the asylum seekers. Their frustration regarding a system that provides no resolution is often expressed in abusive behavior, as they push migrants - and potential refugees among them - back across borders, often with brutality.

A 34-year-old Iraqi Turkoman from Kirkuk who said that he made 10 attempts to cross into Greece before succeeding provides another typical example. "One time I crossed the river into Greece and arrived in Komotini," he said. "They put us in jail for five days and then took us to the river and pushed us back. We were 60 persons. They put us in a small river boat with a motor in groups of 10. They did it in the middle of the night. It was raining hard, and the Greek police started beating us to make us move more quickly. I saw one man who tried to refuse to go on the boat, and they beat him and threw him in the river. They beat us with police clubs to get us to go on the boat."

The report contains recommendations to the Greek government and the European Union, including:

- As the UN High Commissioner for Refugees has urged, other EU states should suspend transfers of asylum seekers back to Greece under the Dublin II regulation and instead should examine their claims themselves;

- The Greek government should make a public commitment to ensure that migrants apprehended in Greek territory or at the border - whether on land or at sea - are treated in a humane and dignified manner, are given the opportunity to seek asylum if they choose, and are not subjected to forced return to Turkey; and

- Greece should immediately stop the routine and systematic police practice of gathering migrants in police stations in the Evros region, trucking them to the Evros River, and sending them across the border secretly in small boats.

"A more equitable and better-managed approach by the EU might have put less of a burden on Greece and resulted in better protection for Iraqi refugees," said Frelick. "But whatever the EU's failures, this does not relieve Greece of its own responsibility to treat all human beings humanely and its obligation not to return refugees and asylum seekers to persecution, or anyone to the real risk of inhuman and degrading treatment or worse."