Summary

Souleymane K. (not his real name) left his home in Côte d’Ivoire alone in 2022, when he was 15. After a beating by a potential human trafficker that left deep scars, he went to Mali, where he spent six months working long hours performing domestic work. He eventually made his way to Libya, where he was arbitrarily detained in Sabratha by an unidentified group and was regularly beaten by guards. After three months, he was let go after paying a bribe and managed to board a Zodiac, a large inflatable boat, with over one hundred people. A Navy ship rescued the group after two or three days at sea and took them to Italy.

He faced racism and other discriminatory treatment in Italy, he told Human Rights Watch, and decided to travel to France. When he reached Ventimiglia, an Italian town on the French border, he met a Guinean boy and they attempted to cross into France together by train. After two successive attempts when French police stopped them and made them return to Italy, they walked through the Alps for a full day to reach Nice, in France. “It took over a full day of walking in the mountains. It was hard, we walked, we walked, we walked so much,” he told Human Rights Watch.

Once in Nice, he slept on the street for two nights until a stranger offered to buy him a train ticket to Marseille. Upon arriving in Marseille, he slept underneath the staircase of the Marseille-Saint-Charles railway station for three nights before a volunteer from a local association found him and accompanied him to the police station so he could file a declaration that he was unaccompanied.

The child protection agency placed him in temporary emergency accommodation pending an assessment to determine whether he was under age 18, and therefore eligible for children’s services. After one month, he received a negative age assessment for reasons he still does not understand:

They put me in a hotel, where they watched me. After the evaluation, they told me I was an adult because I like to go outside during the day to play football. They said that because I don’t stay in the hotel, I am too independent to be a child. I failed my evaluation on Friday and the following Monday I was forced to leave the hotel. I slept on the street for a week until a friend put me in touch with an association helping kids like me.

Souleymane is among the thousands of unaccompanied children who leave their country and travel to France each year. Once in France, these children frequently undergo age assessments to determine whether they will be taken into care by the child protection system (Aide Sociale à l’Enfance, ASE) and receive services such as legal assistance, the appointment of a guardian, accommodation, health care, and education.

Unaccompanied migrant children in France are entitled to temporary emergency accommodation (accueil provisoire d’urgence, APU) while awaiting age assessments. Yet many experience delays of weeks or months before they receive shelter.

Age assessments typically include an observation period, a review of identity documents, and an interview. In Marseille, 50 percent are initially denied formal recognition as children. As in Souleymane’s case, these outcomes often appear to be the product of arbitrary reasons that improperly discount children’s testimony and other evidence. An immediate consequence of a negative age assessment is eviction from emergency shelter, subjecting children to life on the street, degrading treatment, and risk of violence, exploitation, and trafficking.

Appealing an adverse decision is possible, and nearly 75 percent of children in Marseille who seek review of their case before a judge ultimately succeed in having negative age assessments overturned. However, the process is time-consuming; review by the courts can take months or even years. In the interim, delays in formal recognition as children preclude children from entering the child protection system and accessing rights afforded to them, including housing, health, and education.

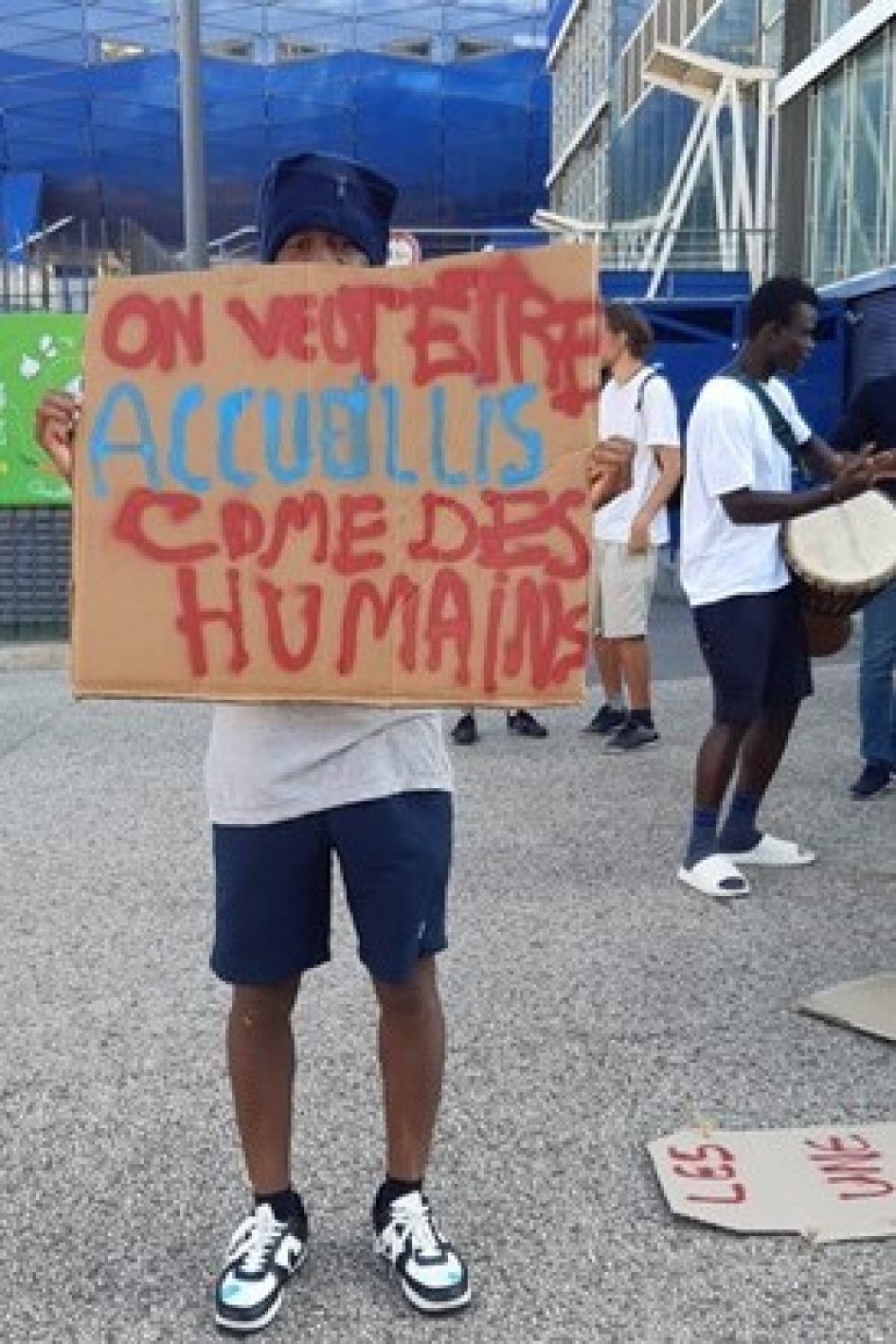

In Marseille, while children wait for a judge to hear their case, they often sleep outside the Marseille-Saint-Charles railway station or elsewhere on the streets until they find assistance through a network of local associations that run squats or individuals who volunteer space in their homes. Without the help of such private initiatives, these children would be homeless.

Negative age assessments and extended periods in judicial limbo take a toll on children’s physical and mental health. After long and dangerous journeys, the overwhelming majority of migrant children arrive in Marseille showing symptoms of post-traumatic stress and deterioration in their mental health, and with no access to psychosocial support. Because they are ineligible for France’s universal health care system without formal recognition as children, their health needs are not always identified and met, and medical treatment and psychosocial support may be delayed.

A healthcare worker treating unaccompanied migrant children at a free health center in Marseille said, “We see a lot of health problems related to post-trauma from the voyage these kids take to get here. Many get injured along the way but never get care, and almost all of them suffer psychological distress, manifesting in the form of headaches, difficulty sleeping, and stress.”

In addition, unaccompanied young migrants are in a state of limbo: the child protection system has decided that they are not children, but the health system does not regard them as having complete autonomy over their health decisions until they are adults. As a result, they are often refused medical authorization for surgeries and interventions.

A., a pregnant teenage girl from West Africa, was accompanied by a social worker from Le Comede, an association providing health services to asylum seekers in Marseille, to the hospital to seek an abortion. When Human Rights Watch spoke to the social worker in June 2023, A. was entering her second trimester and still had not undergone the procedure because the date of birth on her identity documents was not consistent with paperwork from the department deeming her an adult. She was nearing the time limit for legal abortion on request in France, which is the fourteenth week of pregnancy. (In this and other descriptions of medical cases, at the request of the individual or the organizations working with these children, we identify the child only by a randomly chosen initial.)

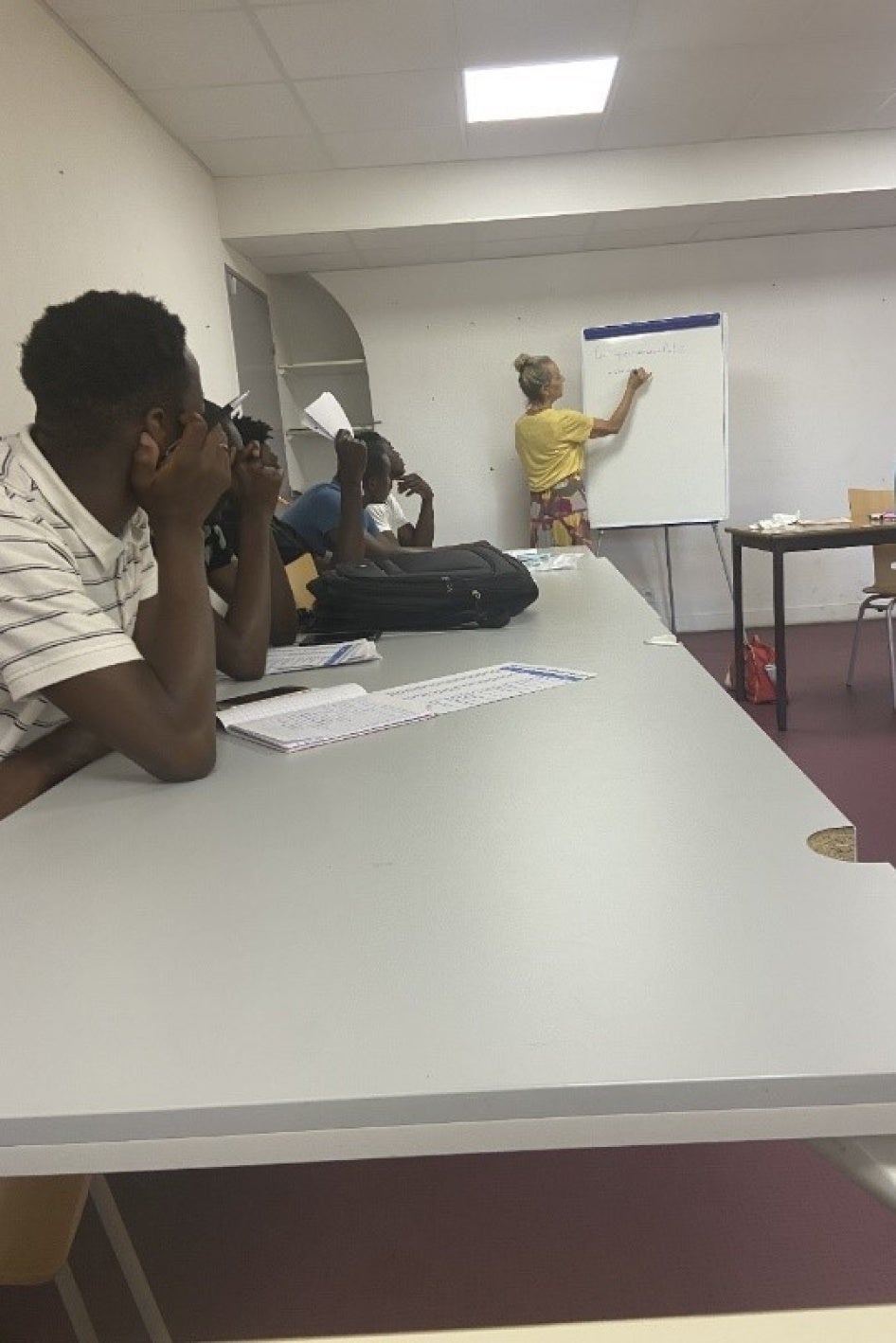

While in principle the right to education is guaranteed to all children regardless of migration status, unaccompanied migrant children in Marseille experience delays enrolling in school during the time they are seeking review of an adverse age determination. Even when their age is accepted by school authorities, most of the children we spoke with waited months to be placed in school because there were no spots available for them. In one such case, Isaac T., a 15-year-old from Côte d’Ivoire who was awaiting the outcome of judicial hearings when we spoke with him in June, told us, “Studying in France was my dream, but now I’m not sure it will ever happen… I took the school placement test so long ago, but I still don’t go to school,” explaining that he had been in France for six months and still had no school placement.Prolonged periods of time in legal limbo also have implications for a child’s regularization of legal status upon adulthood. Under French law, children do not need a visa or residence permit (titre de séjour) to stay in French territory, whereas adults—and those who are not formally recognized as children—are subject to detention and deportation without these documents. Once they reach adulthood, children have the opportunity to receive residence permits or in some cases citizenship, depending on their age at entry into the child protection system, meaning that delays in formal recognition of minority can have ongoing consequences for legal status.

In one such case, Koffi T., a 17-year-old Ivorian boy, was formally recognized as a child on the eve of his eighteenth birthday. A volunteer from Collectif 113, an association helping unaccompanied migrant children based in Marseille, told us, “Now we must hurry to make sure he is placed in a school by next fall so that by his nineteenth birthday, he will have been in some sort of professional training for at least six months. It’s a race against

the clock.”

Glossary

ADDAP 13 Association Départementale pour le Développement des Actions de Prévention des bouches-du-rhônes (13), a nonprofit agency mandated by the Bouches-du-Rhône department to conduct age assessments of unaccompanied children and provide for their care and protection

AME Aide médicale de l’État, State Medical Aid, health care for individuals with irregular migration status

APU Accueil provisoire d’urgence, temporary emergency accommodation

ASE L’Aide Sociale à l’Enfance, the child protection system in France

CASNAV Centre Académique pour la Scolarisation des élèves allophones Nouvellement Arrivés et des enfants issus de familles itinérantes et de Voyageurs, Academic Center for the Education of Newly Arrived Allophone Students and Children from Itinerant and Travelling Families CCAS Centre Communal d'Action Sociale, local social welfare center

CeGGID Centre gratuit d'Information, de Dépistage et de Diagnostic, free center for HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) information, screening, and diagnosis

CESEDA Code de l'entrée et du séjour des étrangers et du droit d'asile, Code of entry and residence of foreigners and right of asylum CHRS Centre d'Hébergement et de Réinsertion Sociale, Accommodation and Social Reintegration Center

CLAT Centres de Lutte Anti-Tuberculeuse, national tuberculosis control centers

C2S Complémentaire Santé Solidaire, subsidized supplementary health insurance that covers expenses not covered by universal health care Department An administrative division of France. Marseille is the prefecture, or capital, of the Bouches-du-Rhône department.

Juge des enfants Juvenile court judge, exercising oversight of children at risk

Jugement supplétif Supplementary judgment, a procedure that allows a judge to order issuance of delayed or replacement birth certificates, typically upon the production of witnesses who can attest to a child’s birth and parentage

MNA Mineur non accompagné, unaccompanied migrant child

OPP Ordonnance de placement provisoire, temporary placement order, an order directing departmental authorities to provide an individual with housing while waiting to undergo the age assessment process or awaiting the outcome of judicial proceedings

PASS Permanence ď Accès aux Soins de Santé, hospital-based medical centers for individuals without health care coverage DPJJ La Direction de la Protection Judiciaire de la Jeunesse, Directorate for Youth Protection and Juvenile Justice

PUMa Protection Universelle Maladie, universal health care for individuals who are legally resident in France

115 An emergency phone number those who are homeless in France can use to find temporary shelter

Recommendations

To the French State

- Ensure that all departments have sufficient funding and resources to carry out their child protection functions. · Ensure a sufficient supply of housing for all unaccompanied children in France, including by increasing spaces in emergency accommodation shelters.

To the Child Protection System (Aide Sociale à l’Enfance, ASE), the Bouches-du-Rhône Departmental Council (Conseil départemental), and Association Départementale pour le Développement des Actions de Prévention des bouches-du-rhônes (13) (ADDAP 13)

- Ensure age assessments are used only when there are serious and credible doubts about an individual’s claim to be under the age of 18. Age assessments should seek to establish approximate age through interviews and review of documents, as recommended by international standards. These procedures should afford the benefit of the doubt, in line with international standards, so that if there is a possibility that an individual is a child, that individual is treated as a child.

- When there are serious uncertainties about an individual’s claim to be under the age of 18, ensure the age assessment procedures used are multidisciplinary in nature and conducted in a manner “characterized by neutrality and compassion.”

- Ensure that age assessments are conducted in a way that is sensitive to the child’s age, sex, gender, psychological maturity, and emotional state.

- Ensure that qualified interpreters assist unaccompanied migrant children.

- Provide unaccompanied children with verbal and age-appropriate information about their rights and entitlements in France as children.

- Ensure that all those who are awaiting an age assessment receive immediate emergency accommodation for the minimum period of five days or until the evaluation is completed, as required by article R.221-11 of the Code of Social Action and Families.

- Ensure that the period of emergency accommodation is extended to cover any period of appeal of an adverse age determination.

- Establish suitable separate accommodation for young adults and age-disputed cases, and in the meantime, ensure that there are adequate and protected places in existing facilities.

- Ensure that emergency accommodation is safe, sanitary, child-friendly, and consistent with human dignity.

- Issue and implement clear guidance to staff at ADDAP 13 that age assessments should follow French regulations, which require a comprehensive social evaluation by trained staff. In particular:

- Apply the presumption of minority, as required by French law.

- Afford the benefit of the doubt such that if there is a possibility that an individual is a child, he or she is treated as such.

- Consider foreign birth certificates and other civil documents as genuine unless there is concrete evidence to the contrary.

- Implement the best practices guide published by the Directorate General of the French Ministry of Health (Direction générale de la Santé, DGS) and the Directorate General of the Ministry of Solidarity and Social Cohesion (Direction générale de la Cohésion sociale, DGCS). In particular:

- Ensure that within 48 hours of entering temporary emergency accommodation (APU), children benefit from an initial health assessment, distinct from the age assessment process, focusing on both physical and psychological aspects.

- Ensure that children have a comprehensive medical appointment, distinct from the age assessment process, with a state-certified nurse in close collaboration with a doctor at least three days after they are “stabilized in securing their basic needs.”

- Ensure that health assessments include sexual and reproductive health care, including informed and consensual screening for pregnancy, risk of violence, contraceptive needs, and access to emergency contraception or abortion if needed.

- Ensure that medical professionals evaluating children are appropriately trained in children’s health, cultural factors, and health outcomes related to migration, including post-traumatic stress and sexual and other gender-based violence.

- Ensure that health assessments are conducted in a confidential, patient-centered manner.

- Consider mental health and psychological well-being when determining if an individual is fit to undergo an age assessment.

- Provide children with their personal health information collected during the evaluation stage.

- Ensure that children have access to health care, including rights-respecting mental health care and psychosocial support.

- Ensure that children who have experienced mental health distress and/or have a mental health condition have access to reasonable accommodation during the age assessment process to ensure they can meaningfully participate.

- Ensure follow-up care and remind children of scheduled medical appointments.

- Extend comprehensive universal health protection (Protection Universelle Maladie, PUMa), supplemented by complementary health insurance (Complémentaire Santé Solidaire, C2S), through any period of appeal of an adverse age determination.

To the Juvenile Court (Tribunal pour Enfants)

- Judges should review negative age assessments without delay.

- Judges should apply the presumption, as set forth in article 47 of the Civil Code, that identity documents issued abroad are valid.

To the Government, the National Assembly, and the Senate

- Amend the Code of Social Action and Families to specify that age assessments be used as a matter of last resort, only when there are grounds for serious doubts about an individual’s declared age and where other approaches, including analysis of documentary evidence, have failed to establish an individual’s age.

- Ensure that eligibility for residence permits and nationality upon reaching adulthood is calculated from the date an individual first seeks care from the child protection system, rather than the date they receive formal recognition, so that they are not disadvantaged by delays in the age assessment process.

To the Ministry of Education

- Ensure that all unaccompanied migrant children in France have access to education, in line with French law and international standards.

- Ensure that children are enrolled in school without delay.

- Ensure that school authorities have the necessary resources to provide education for all children, and to provide psychological counseling when needed.

To the Ministry of Health and Prevention

- Ensure that all unaccompanied migrant children have the right to timely and unconditional access to comprehensive universal health protection (PUMa and C2s) upon entering the period of temporary emergency accommodation.

- Ensure that adequate and rights-respecting mental health services and psychosocial support are available for all individuals.

- Make interpreters available for medical appointments, including those for mental health services.

- Ensure that unaccompanied migrant children are able to receive without delay the health care they need, including the full range of sexual and reproductive health care services, through appropriate steps such as the removal of barriers to effective access, such as formal or de facto requirements for them to be under the care of the child protection system.

Methodology

This report is based on 58 interviews, including 18 with asylum seekers and migrants in Marseille who identified themselves as children under the age of 18. All unaccompanied migrant children interviewed were male: the vast majority of unaccompanied migrant children entering France are boys, and although we attempted to identify unaccompanied girls who would speak with us, we were unable to do so. The interviews were carried out between March 2023 and July 2023. The unaccompanied children were from Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Gambia, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, the Republic of Guinea (often referred to as Guinea Conakry to distinguish it from Guinea-Bissau and Equatorial Guinea), and Sierra Leone.

In addition, Human Rights Watch spoke with 40 staff of humanitarian agencies, lawyers, health care providers including pediatricians, other doctors, social workers, child psychologists, local authority workers, and volunteers who assist with housing and legal proceedings, or run activities for young migrants and asylum seekers in Marseille.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed case files, including negative age assessments issued by the Association Départementale pour le Développement des Actions de Prévention des bouches-du-rhônes (13) (ADDAP 13), the association delegated by the Bouches-du-Rhône departmental council to conduct age assessments. Human Rights Watch met with ADDAP 13 and subsequently sought and received its written observations on the findings of this report.[1] We have included excerpts of these observations in relevant sections of the report. Human Rights Watch also sought written comment from the Bouches-du-Rhône departmental council but did not receive a reply before this report was finalized for publication.[2]

Human Rights Watch researchers conducted interviews in French and English. Before each interview, we explained to all interviewees the nature and purpose of our research, that the interviews were voluntary and confidential, and that they would receive no personal service, benefit, or compensation for speaking to us. We obtained verbal consent from each interviewee, and all interviewees were told they could stop the interview at any time and decline to answer any question. Interviews were semi-structured and covered a range of topics related to access to health care, housing, legal representation, and children’s rights. Most interviews were conducted in person and some by phone. The average length of each interview was approximately one hour. Human Rights Watch took precautions to avoid re-traumatizing the children interviewed for this report.

All names of children used in this report are pseudonyms. In descriptions of medical cases, we assigned a pseudonym consisting of a randomly chosen initial and omitted the precise age, country of origin, and date of arrival at the request of the individual or the organizations working with these children.

In line with international standards, the term “child” refers to a person under the age of 18.[3] As the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child and other international authorities do, we use the term “unaccompanied children” in this report to refer to children “who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so.”[4]

The term “migrant” is not defined in international law; our use of this term is in its “common lay understanding of a person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, and for a variety of reasons.”[5] It includes asylum seekers and refugees, and “migrant children” includes asylum-seeking and refugee children.[6] Some groups in France, including the French Defender of Rights (Défenseur des droits, DDD), use the term “exile” in preference to “migrant.”[7]

Unaccompanied Migrant Children in Marseille

Tens of thousands of young migrants arrive in France each year on their own.[8] While arrivals diminished in 2020 due to movement restrictions linked to the Covid-19 pandemic, the number of unaccompanied migrant children received by departments across France increased in 2021 and 2022.[9] Marseille is no exception: in 2022, there were an estimated 950 unaccompanied migrant children registered as having entered the city, of which only 2 percent were girls, according to the nongovernmental group delegated by the Bouches-du-Rhône department to handle their reception and evaluation.[10] While Marseille is a destination city for unaccompanied migrant children,[11] the number of unaccompanied children who travel there each year is not particularly large in absolute terms, meaning that child protection authorities should be able to make adequate arrangements for these arrivals.

Some children choose to come on their own to Marseille because they speak French and because of their sense of historic ties between their home countries and France. Others have no explicit destination in mind when they leave their home country. Many of the children Human Rights Watch spoke with ended up in Marseille by chance because of individuals who helped them on their journey, or because they encountered difficulties or discrimination in other places.

Once in Marseille, half of all unaccompanied children who undergo age assessments are denied recognition of their minority.[12] The reasons for denial often seem arbitrary, a conclusion that is reinforced by the fact that nearly 75 percent of those who appeal the decision ultimately receive formal recognition as children, according to estimates from lawyers providing legal assistance to these children.[13] In the meantime, however, they experience protracted periods of uncertainty and remain in limbo, without access to health care, housing, and specialized child protection services.

Most unaccompanied migrant children we spoke with in Marseille were from West Africa. The most common countries of origin were Guinea, Mali, and Côte d’Ivoire, groups that work with unaccompanied children told Human Rights Watch.

The reasons children gave for leaving their country of origin varied. Many of the children Human Rights Watch spoke with described fleeing abusive family situations, particularly after the death of one or both parents. For example, Ibrahima N., a 16-year-old boy from Guinea, said, “When my father died, I had to go live with my dad’s younger brother, and he was not nice to me. He had two wives and my mother refused to become his third wife and he let that anger out on me. He hurt me. Until one day my neighbor helped me leave.”[14]

Some children said they were targeted or threatened because of their or their families’ religion or perceived political views. “My dad arrived home one day, I was eating, and he said I needed to finish fast since we had to run,” Kwame B., a 15-year-old Ghanaian, told us, explaining that his father was politically opposed to the local government. “He is my father, he’s my everything, so when he told me to follow him, I listened.”[15]

Others left their home countries after being subjected to trafficking or forced labor. For example, Souleymane K., the 16-year-old from Côte d’Ivoire whose account appears at the beginning of this report, showed us scars on his face that he said were from a trafficking ringleader:

I loved going to school, but I stopped because my mother didn’t have the means to pay. Then I met a man on the street who told me to come to his house because he would find me work. I went and there were so many kids there. I stole for this man. We didn’t have a choice … I needed to do it to have food for me and my mom. If we didn’t bring anything back to his home at the end of the day, he would hit and cut us.[16]

Most children we spoke with traveled by land to Libya, crossed the Mediterranean by inflatable boat to Italy, and then took the train or walked through the Alps to arrive in France. We heard numerous accounts of boats that ran out of fuel or broke down at sea. Sixteen-year-old Malick S. from Guinea made the crossing in the winter of 2023 in a boat that capsized. “We ran out of gas. Everyone started to get so scared, water entered the boat, and many of us jumped into the water,” he said. Five hours later, a ship rescued the survivors and took them to Italy. He continued, “As soon as we were evacuated and I was in the hospital, I started to feel a lot of pain. I was so scared in the water that I didn’t notice how cold my body was until I had time to realize what I was feeling.”[17]

Several unaccompanied children described being separated from a relative, parent, another trusted adult, or friend on the journey. Kwame B., the 15-year-old Ghanaian, said, “My father and I were separated when we took different boats to leave Libya … now I don’t have a mother or a father. Where should I go?”[18] Mamadou O., a 16-year-old from Guinea, watched his football trainer drown in the Mediterranean when their boat sunk. He told us, “I didn’t know the way, but my trainer did … we left him in the water, he died there. I never saw him again.”[19] Ibrahima N., a 16-year-old boy from Guinea, explained:

I left Guinea with my neighbor. I was with him until Tunisia but there was not enough room on the boat, so I went alone. I was very scared. I even cried. When I arrived in Italy, I called a friend to find out what happened to my neighbor. He told me that his ship had sunk and that he passed away.[20]

Arduous journeys, unstable living conditions, and lack of access to child protection have adverse consequences on unaccompanied migrant children’s physical and mental health. Psychologists, social workers, and doctors all told Human Rights Watch that children frequently arrive in Marseille in critical or vulnerable states. “When they get to France, these kids are often psychologically traumatized and in very poor health … many arrive in a fragile and chronically exhausted state linked to lack of access to basic needs,” a social worker treating children told Human Rights Watch.[21]

The cases in this report document the harmful consequences of erroneously and arbitrarily considering unaccompanied children as adults and keeping them outside of the child protection system in Marseille. While these children wait for their case to be heard by the juvenile judge, they live a precarious existence where they are denied the right to housing, health, education, and food and deprived of essential needs, including clothing and hygiene.

A controversial new immigration bill adopted in December 2023 included numerous regressive provisions,[22] including restrictions on social benefits for noncitizens,[23] on birthright citizenship for children born in France to parents who are not French,[24] and on family reunification.[25] The Constitutional Council, which reviews the constitutionality of legislation, struck these provisions on procedural grounds, along with many others, in a ruling issued on January 25, 2024.[26]

The immigration bill also authorized the creation of a new registry of “delinquent unaccompanied minors” (mineurs non-accompagnés délinquants)[27] that authorities would presumably use in decisions on residence permits and citizenship applications made by unaccompanied youth at age 18. The Constitutional Council allowed this provision to stand.[28]

A measure that would have abolished state medical aid (Aide médicale de l’État, AME) for people in irregular migration status was dropped from the bill before its adoption, although the government has committed to a reform of the health system in 2024.[29] The bill retained a proposal to prohibit the administrative detention of noncitizen children, initially limited to children under 16 but amended before enactment to apply to all children under 18.[30]

It was not immediately clear how the bill’s remaining provisions would affect unaccompanied young migrants who have received a negative initial age assessment and are seeking review of their cases by the juvenile judge.

Arbitrary Age Determination Practices

Each administrative department in France handles the reception and evaluation of unaccompanied young migrants in its own way. Some departments carry out age assessments themselves; others contract with agencies to do so. For Marseille and elsewhere in Bouches-du-Rhône, the department has designated the Association Départementale pour le Développement des Actions de Prévention des bouches-du-rhônes (13) (ADDAP 13), a nongovernmental group, to evaluate the child’s situation to confirm whether he or she is under the age of 18 and determine his or her unaccompanied status.

Child protection is a departmental responsibility, not a national one, meaning the department covers most of the costs related to unaccompanied migrant children who are taken into care. The care of one unaccompanied child by the child protection system (Aide Sociale à l’Enfance, ASE)—covering accommodation, food, education, and training—costs on average 50,000 euros per year.[31] As Human Rights Watch has observed in its reporting on the situation of unaccompanied children elsewhere in France, this financial obligation can create an incentive to subject unaccompanied children to unnecessary and abusive age assessments.[32]

While half of all unaccompanied children who undergo age assessments in Marseille are initially denied recognition of their age, nearly 75 percent of those who seek review are ultimately granted minority status by a juvenile judge.[33]

Age Assessments

The assessment is aimed at evaluating the individual’s “declarations regarding his identity, his age, his family of origin, his nationality and his unaccompanied status.”[34]

International standards call for children undergoing age assessments to receive the presumption of minority and the benefit of the doubt “such that if there is a possibility that the individual is a child, he or she should be treated as such.”[35] But as Franck Ozouf, manager of the unaccompanied migrant children (MNA) project at Secours Catholique Caritas France, remarked, “The presumption of minority exists in law to a certain point but no longer exists in practice. When the department refuses to recognize a child’s minority and unaccompanied status, there is a real legal void in terms of protection. Even if the child is eventually brought before the juvenile judge, there is no emotional appeal, there is no welfare, there is no accompaniment.”[36]

By law, the evaluation should take the form of a “multidisciplinary” interview that considers the youth’s reasons for leaving the country of origin, family background, and state of unaccompanied status.[37] Evaluations should also be conducted in a manner “characterized by neutrality and compassion.”[38] However, the age assessment process in Marseille does not appear to take into account children’s emotional and communication needs, despite the well-documented effects of post-traumatic stress disorder on memory, concentration, and the expression of emotion.

Age assessments for unaccompanied migrant children in Marseille should last between 45 minutes and one hour and a half.[39] Several children we spoke with said their interviews were much shorter. In addition, children said they did not always understand the purpose of the interview, the examiners’ questions, or the interpreter. “My ADDAP 13 examiner was Senegalese, and we didn’t speak the same language … she didn’t understand me, and I didn’t understand her. I didn’t know French, so I spoke in Susu and that was it. The evaluation was about a half hour and then they told me I wasn’t a minor,” Salimatou A., a 17-year-old boy from Guinea, told us.[40]

Upon completing the age assessment, the child is either recognized as a minor and taken into care by the child protection system (ASE) or declared an adult and thus disqualified from any material benefits afforded to children or eligibility for residence permits upon adulthood.

According to lawyers in Marseille, until a year ago, children waited several months to undergo age assessments, but now ADDAP 13 evaluates children within one week of arrival.[41] Volunteers, lawyers, and doctors told us that while the shorter time frame is a positive development in the sense that youth are not waiting for protracted periods without having the opportunity to begin the age assessment process, it also means that those who receive negative age assessments are stripped of accommodation and protection more rapidly.

A doctor who treats unaccompanied migrant children in Marseille commented that “[t]he institutions are completely saturated and conduct quicker age assessments … children are therefore placed in shelters to be assessed, often after several weeks of waiting, then for some, quickly put back on the street without being granted any rights.”[42] This is consistent with statistics provided by ADDAP 13 showing that the number of unaccompanied migrant children in Marseille who were formally recognized and taken into care by the child protection system in 2022 was nearly 25 percent lower than what was recorded in 2021.[43]

Frequent reasons listed for denying children in Marseille formal recognition as children were “physical appearance,” “stress,” “confusion and inconsistency of speech,” and “too much confidence,” lawyers from the Unaccompanied Minors Commission of the Marseille Bar Association told Human Rights Watch. Such grounds and the lawyers’ observations during interviews suggest that examiners are evaluating children too soon after their arrival in Marseille, before they have recovered from their journey, and not adequately taking into account the impact of children’s time in transit. “They are presented an ‘initial contact form’ which has [the child’s] photo on it … a photo taken when the child had just arrived in France after an arduous journey and has slept on the street for several nights,” lawyers with the Marseille Bar Association’s Unaccompanied Minors Commission said.[44]

Human Rights Watch reviewed case files that suggest other arbitrary grounds on which authorities have rejected children’s claims to be underage. In one case, a boy received a negative age assessment based in part on his decision to call his lawyer to ask for help with a health condition. On his denial letter, it stated “when he has concerns, he prefers to refer to his lawyer.”[45]

In fact, lawyers with the Marseille Bar Association’s Unaccompanied Minors Commission said, “From the documents we are presented when taking on cases, it seems to us that there are many ADDAP 13 evaluators making their decision [regarding the child’s minority] before they even meet them in person.”[46]

Such accounts and the case files Human Rights Watch reviewed are similar to those we saw in Paris and the Hautes-Alpes, where some youths requesting protection from the child protection system received negative assessments based on appearance alone, and others were rejected on other clearly arbitrary grounds, including work in countries of origin or transit, irritation in the face of repeated questions, or responses that are consistent with trauma.[47]

ADDAP 13 included the following points in its written reply to Human Rights Watch’s request for comment:

Our assessments are carried out by a multidisciplinary team made up of legal experts and specialized educators. The framework and objectives of the assessment mission are clearly formalized for both professionals and individuals presenting themselves as minors.

. . . .

Interviews are systematically conducted by a legal expert from our team, with the assistance of an interpreter whenever necessary to ensure legality and fairness. At the end of the interview, a meeting is organized with the multidisciplinary team to reach either a clear minority/majority decision or, in case of doubt, a request for further information.

When they are admitted to the shelter, young people are taken into care by the educational team and systematically asked in which language they would like the interview to be conducted. Interpreters are physically present, except when there is no interpreter in the area for the language requested. In this case, we use a telephone service. At the start of the interview, the young person is systematically asked to confirm that he or she understands the information exchanged with the interpreter. The young person can ask the evaluators to change interpreters at any time. In this case, the interview is stopped and postponed until a suitable interpreter meeting the needs of the young person can be found.

. . . .

If the young person's emotional, physical, or psychological state prevents him/her from expressing him/herself or answering questions, the interview will be postponed…. If several interviews are necessary, they must be at least 24 hours apart, and if necessary, other professionals must be called in.

Throughout the interview, the evaluators check with the young person to make sure they understand the exchanges. If there are any notable inconsistencies in the story, the evaluators point this out so that the young person can go back over his or her explanations if he or she so wishes. In accordance with the decree of November 20, 2019, the topics addressed in the context of gathering the young person's views are identical for all interviews: the person’s identity; specific elements if a civil status or identity document is presented; family situation; living conditions in the country of origin; reasons for leaving, stages and conditions of the migratory journey; conditions of entry and life in France; plans; overview of human rights, asylum, and human trafficking.

. . . .

There are no instructions given to evaluators ‘on the relevance of assessing age on the basis of elements such as traveling alone, working during migration, and speaking French or other languages that are not the native language.’ They are asked to apply the regulatory provisions as well as the recommendations for good professional practice, which are published by the French National Authority for Health (haute autorité de santé, HAS) and worked on as a team. Furthermore, as already indicated, our teams do not assess the age of the people they interview, but rather their isolation and minority status.[48]

The Appeals Process

With the help of volunteers from several humanitarian groups, youth who are faced with denial of age recognition are connected to a lawyer to help them seek review of adverse age assessments before a juvenile judge.[49] A lawyer from the Unaccompanied Minors Commission of the Marseille Bar Association told us:

Each week, we receive 15 requests ... this doesn’t mean we necessarily take on 15 new cases because some [children] may choose to continue on to a different department. But I would say we take on about 10 new cases each week.[50]

The juvenile judge is not bound by any timeline to review cases. According to lawyers, the process takes on average three to six months but can last as long as a year. Omar J., an 18-year-old Gambian boy, was 16-and-a-half when he began his appeals process.[51] He was recognized as a minor by the juvenile judge two weeks before his eighteenth birthday, a considerable delay that was consistent with other cases reported to us.[52]

Human Rights Watch also heard of cases where delays were so long that hearings were set to take place after the child’s eighteenth birthday. Such instances can affect children’s eligibility for residence permits and French nationality.

Arbitrary Requirements for or Rejection of Identity Documents

The age determination process has become increasingly difficult because evaluators and some judges require children to produce specific documents even though the applicable regulations call for a holistic assessment based on the child’s account and other available evidence. Since many children either leave their country of origin without their identity documents or lose them in transit, the de facto requirement to produce documents frequently leads to delays in considering cases.

Mamadou O., a 16-year-old from Guinea, arrived in Marseille after making a crossing to Italy in a boat that held more than 40 people and capsized. He told Human Rights Watch that he was surprised to receive an initial negative age assessment. He said, “They told me that without my paperwork, they couldn’t say I was a minor. But I came on a boat, I didn’t have the documents in my pocket. My mother had them [in Guinea] and she passed away once I arrived in France.”[53]

Kwame B., a 15-year-old Ghanaian who was denied his minority in September 2022 and by January 2024 had still been waiting for a judge to review his case, said, “There are a lot of problems with my papers. In December 2022, I went to Paris to do my passport because the lawyer said I had to. Seven months have passed and nothing.”[54]

Children who do have documents are also frequently rejected. Despite the presumption in French law that foreign documents are valid[55]—and international standards noting that “documents that are available should be considered genuine unless there is proof to the contrary”[56]—child protection officials regularly ask for documents such as birth certificates or passports to be authenticated by embassies. Volunteers, lawyers, and children themselves said that this process is costly and can take months. Children seeking review of adverse age assessments also face obstacles as judges increasingly exclude their identity documents from consideration. According to the Unaccompanied Minors Commission of the Marseille Bar Association, there are now more judges requiring a procedure known as a jugement supplétif, or “supplementary judgement,” which typically requires the production of witnesses in a court in the country of origin who can attest to a child’s birth and parentage.[57] Drissa K., a 16-year-old boy from Côte d’Ivoire, expressed anxiety at the time of our interview because his mother didn’t have the money to travel from his hometown to the capital to obtain a supplementary judgement on his behalf.[58] Even when children have certified documents issued by a judge in the country of origin, French officials often refuse to consider them. “I don’t know what more they want from me. I’ve filed my paperwork; I have my certified consular document with a supplementary judgment … now my lawyers tell me that I need a passport. But I don’t have the means to go to Paris alone to get it, so I’m stuck,” Seydou K., a 15-year-old boy from Burkina Faso, told Human Rights Watch.[59]These accounts are not uncommon. According to a volunteer from the association Soutien 59 Saint-Just that helps unaccompanied migrant children gather and authenticate documentary evidence of age, providing supplementary documents does not necessarily guarantee that a child will receive an audience in front of a juvenile judge: “I’ve helped children who got very attached to the idea of their biometric passport arriving, only to later be refused an audience with the judge,” he told us.[60] This is not unique to Marseille: in March 2023, a Pakistani teenager was denied recognition of his minority in Lyon despite providing original copies of his birth certificate and identity card to the juvenile judge.[61]

ADDAP 13 included the following in its written reply to Human Rights Watch’s request for comment:

With regard to identity documents presented during the assessment interview, please note that the possibility of having civil status documents has no direct bearing on the assessment. If the young person has such documents and wishes to present them to the evaluator, the latter will ask him/her whether he/she wishes to entrust them to the service or have them photocopied. If the young person's response is positive, the documents will be secured by a procedure whereby they are placed in a safe by a department manager on the administrative premises, with access strictly limited and controlled. A register will be kept, and a receipt for the deposit of the document will be given to the young person, together with a copy of the deed. At this point, the evaluators explain to the young person the risks to which he or she may be exposed in the event of presenting false papers or declarations. If the young person accepts, the service will forward the document to the Departmental Council, which will have the option of submitting it to the border police for documentary examination if there is any doubt as to the young person’s minority.[62]

Lack of Access to Housing

Half of all unaccompanied migrant children entering Marseille receive a negative age assessment. As an immediate consequence, within 48 hours of an adverse age determination, children who are deemed to be adults are evicted from emergency accommodation provided by ADDAP 13,[63] even though many will eventually receive formal recognition of their minority when a judge reviews their cases. These children find themselves uniquely disadvantaged—they are unable to access the protections afforded to children yet remain ineligible for accommodation in adult reception centers because their identity documents indicate they are under 18.

The failure of the department to provide adequate alternative accommodation means these children must fend for themselves or seek assistance from ordinary citizens or nongovernmental organizations in Marseille to find shelter.

Temporary Emergency Accommodation

Once children present themselves as unaccompanied to ADDAP 13, they are entitled to temporary emergency accommodation (accueil provisoire d’urgence, APU) while they wait for an age assessment.[64] Despite this legal obligation, there have historically been delays of up to four months for children to receive this temporary accommodation.[65] In the meantime, many find themselves living on the streets.

When we asked ADDAP 13 about these delays, its staff initially stated that there are only 150 temporary emergency accommodation spots available in their facilities. Deputy Director David Le Monnier told Human Rights Watch that during the first six months of 2023, the agency had initial contact with about 800 youth in Marseille seeking to enter the minority and isolation assessment process. “The law says that they should enter temporary emergency accommodation with the shortest delays possible. But I won’t hide that in practice, it’s not always as evident as that,” he said.[66] In October 2023, however, ADDAP 13 stated that by the end of 2022, “we achieved immediate sheltering for all young people presenting themselves to our service.”[67] The agency informed us that it had increased the number of available temporary placements to 240:

[A]n increase in the number of migrants presenting themselves as minors can saturate the system and, given the number of spots available, hamper their immediate accommodation. That is why during peak periods, we implement the following system: a substantial increase in the number of temporary placements, without [the need for advance] authorization and on an exceptional basis, in order to be able to shelter as many young people as possible for evaluation. That is why we regularly operate in excess of the 120 authorized spots. At present, following the major waves of migration seen since September, and with the agreement of the Departmental Council, we are taking in more than 240 young people, that is twice the number of regularly authorized spots.[68]

This willingness to address the challenges posed by increases in arrivals is welcome. Nonetheless, we continued to hear in mid-2023 that unaccompanied children faced delays with temporary emergency accommodation. In addition, although beyond the scope of this report, we also heard—and the agency itself observed in a 2022 report—that unaccompanied children whose minority was formally recognized had few suitable options for long-term placements. Pregnant girls and children with mental health needs, among others, faced particular housing challenges.[69]

According to Cyril Farnarier, coordinator of Project ASSAb aimed at improving access to health care for homeless adults, children, and families in Marseille, “There has been an explosion in the number of young migrants on the street in Marseille, but the means provided by the department haven’t followed. While we could legitimately complain that ADDAP13 isn’t doing enough, concretely they don’t have the means to do a good job.”[70]

Human Rights Watch heard numerous accounts of children who arrived at ADDAP13 and were turned away because facilities were at capacity. While some children were taken in by volunteer collectives or families while they waited for a spot to become available, many had no other option but to sleep outside.

Ibrahima N., a 16-year-old boy from Guinea, said that the day he arrived from Italy, a volunteer at the train station oriented him towards ADDAP 13 where he was told there was no spot available for him: “They told me to come back every day. I slept on the street and returned each morning [to ADDAP 13]. There was no room for me until April 13, 11 days later.”[71]

Similarly, Isaac T., a 15-year-old boy from Côte d’Ivoire, said, “I slept underneath the staircase of the Saint-Charles railway station for one week until they had a bed for me at the hotel.”[72] Sixteen-year-old Mamadou O. from Guinea said, “When I arrived, I stayed alone and slept for five days on the street, I didn’t know what else to do.”[73]

In some cases, ordinary citizens open their homes to give children a place to stay for a night or two, or even longer. Kwame B., a 15-year-old Ghanaian boy, told us, “When I arrived in Marseille, ADDAP 13 told me there was nowhere for me yet, so I slept outside for four days. I met a Ghanaian man at the train station … He took me to his house and fed me until finally a week later I got a place in the hotel.”[74]

More generally, children described the uncertainty and distress associated with not having stable accommodation. “It’s hard because I always sleep in squats, and I don’t feel good there. I don’t know where I’ll sleep next,” Moussa E., a 17-year-old boy from Guinea, told Human Rights Watch in June, adding, “This isn’t the France that I imagined. Everyone says that France represents liberty, but I don’t feel free right now. The reality is that if it weren’t for this association [Collectif 113], I would be completely abandoned.”[75]

Seydou K., a 15-year-old from Burkina Faso who arrived in Marseille in November 2022, told us that he had slept in five different beds before arriving at the Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders or MSF) house in the summer of 2023. “It’s exhausting to sleep in so many different places and not know what comes next,” he said.[76]

Children face difficulties accessing shelter in other departments across France. A 2021 report by Le Comede and MSF found that 55 percent of unaccompanied migrant children receiving care at an MSF health center in Paris were homeless, yet only 5 percent of them had lived on the street in their home country.[77]

After complaints filed by associations against the department of Bouches-du-Rhône, and reports by the French Defender of Rights (Défenseur des droits) and the General Inspectorate for Social Affairs (Inspection Générale des Affaires Sociales, IGAS), the delays in granting children temporary emergency accommodation have decreased since mid-2022.[78] However, according to lawyers, volunteers, and humanitarian workers in Marseille, the unforeseen consequence of reduced delays is that children are now denied legal recognition of their age much more quickly and, as described more fully in the next section, face homelessness as a result.

According to Cyril Farnarier, “In order to keep the machinery running under pressure, ADDAP 13 organizes a fast turnover at the hotel … so you have kids being kicked out of the temporary hotel faster than before, over half of whom are reevaluated later on and granted their minority by the juvenile judge.”[79]

Housing Following a Negative Age Assessment

According to volunteers, as of January 2024, there are at least 150 children in Marseille who are not provided with accommodation after a negative age assessment and who face the stress and danger of being homeless.[80]

In the absence of laudable efforts by a strong network of local associations and volunteers, unaccompanied migrant children in Marseille would be left to navigate the uncertainty of finding accommodation on their own. Roughly 20 children are lodged at the MSF shelter for unaccompanied migrant children in vulnerable health; another 25 children sleep in squats run by a group called Collectif 113; 50 children sleep in other squats, three of which are in buildings belonging to the city of Marseille; and 40 are housed with host families through a volunteer-led organization called RAMINA (Réseau d’Accueil des MInots Non Accompagnés).

In rare cases, children are housed in an emergency accommodation and social reintegration center (CHRS, Centre d'Hébergement et de Réinsertion Sociale). However, several volunteers described the shelter as not suitable for children: “[CHRS] are large mixed structures of up to 180 adults, many of whom have been living on the street for years or suffer from substance abuse … it’s a very difficult environment and not meant for children.”[81]

In addition, ADDAP 13 informed Human Rights Watch that it had an agreement with the Departmental Council to accommodate up to 40 young people who are seeking review of negative age assessments:

Over the past year, we have developed a system to enable us to take in people who have lodged an appeal. With the agreement of the Departmental Council, 40 young people are accommodated in one of our facilities in Marseille, when a provisional placement order (OPP) has been issued to enable further investigations (document verification or bone testing). Our aim is twofold: to ensure that these people receive educational, health and social care until the court has made its decision, and to avoid saturating the system so as to be able to place new people in shelters.[82]

This initiative is positive but limited in scope: not only is the number of placements much lower than is needed, but eligibility also appears to be restricted to young people who have already sought judicial review and who have received a provisional placement order.

Nearly every volunteer or humanitarian aid worker whom Human Rights Watch spoke with mentioned having opened their home to a young migrant at some point, ranging from a few nights to months at a time. Dominique Zavagli, former president of the association RAMINA, commented:

When we first meet the youth, we put out a call to RAMINA’s networks to see if we can find them a place to sleep. We have about 200 people on our volunteer list, but only 30 are active. If there is no room to offer them, we do as much as we can … we buy them a slice of pizza, get their phone number, give them a duvet.[83]

Many children indicated that without help from associations, they would have had nowhere to turn. Salimatou A., a 17-year-old boy from Guinea, told us:

The evaluation was about half an hour and then they told me I wasn’t a minor and I had to leave the hotel. I slept there for one more night and then I was put on the street. Later someone gave me the telephone number of a woman [from Collectif 113]. She found me a bed in a room in this squat, and I’ve been here ever since.[84]

Mamadou O., the 16-year-old boy from Guinea, arrived in Marseille in mid-February of 2023. When he received a negative age assessment in March, he had nowhere to go.

He explained:

ADDAP 13 made me leave the hotel and I slept on the street for three days. On the fourth day, I met a man who gave me the number of an association. When I called, they told me, ‘Today, we don’t have room for you, but tomorrow we can try.’ So I slept on the street again. At 8 a.m. the next day, they called me and told me there was a spot for me.[85]

In a similar account, Ibrahima N., another 16-year-old boy from Guinea, told us, “When I did the evaluation, they told me that I wasn’t a minor. They handed me a piece of paper and the following day they made me leave the hotel. Luckily my friend told me to call Collectif 113 to see if they had a spot for me. And then I came here.”[86]

When asked about these accounts, a doctor who treats these children remarked, “When kids are told they’re not minors, the state doesn’t even provide them with nights in a shelter. They are thrown to the streets just like that, like an old pair of socks.”[87]

Sleeping on the street has serious adverse consequences on children’s sense of safety, security, and mental health. Girls on the street are especially at risk of human trafficking and sexual and other gender-based violence. A volunteer told Human Rights Watch:

If you do not have your primary needs met, how can you worry about the rest? How can you go through an appeals process, go to your lawyer, ask for your documents from your country … if you don’t even have a roof over your head? These kids are in a constant state of survival.[88]

Omar J., a Gambian boy, told us he was 16 when he was kicked out of ADDAP 13 accommodation after a negative age assessment. He spent four months living and sleeping on the street until Collectif 113 took him in.[89] A volunteer working at the squat said, “When he arrived at the house, he was so afraid of knives. For the first few weeks, we had to hide all the knives in the house so he would not shake in fear.”[90]

These accounts are not unusual. Federico Colombo, a legal expert, commented:

It’s ironic because ADDAP 13’s motto is “educating in the street” and given the level of abandonment and poor support they give these kids, it’s almost as if ADDAP 13 really believes the street should take care of these kids, and they leave them there.[91]The French state has a responsibility to ensure individuals have access to suitable accommodation, regardless of their age.[92] It has additional obligations toward children, including to provide them appropriate protection and care and ensure their survival and development.[93] Given that three-quarters of initial age assessment decisions are overturned on review, the department should take all feasible steps to ensure that children are provided with suitable accommodation and not left to sleep on the street while they exercise their right to review of negative age assessments.

Barriers to Health Care

The administrative steps required to obtain health coverage in France are complex for adults to understand, let alone for unaccompanied children who have just arrived, many of whom do not speak French. Children awaiting age assessments or who have not received formal recognition as minors are ineligible for comprehensive universal health protection, leading to difficulties in accessing timely care and to frequent refusals of surgeries and operations.

Health Coverage

In France, there are several tiers of health care. For individuals with regularized immigration status and asylum seekers, there is universal health protection (Protection Universelle Maladie, PUMa) which can be supplemented by complementary health insurance (Complémentaire Santé Solidaire, C2S) for individuals with income under a specific level to cover expenses exceeding the state reimbursement threshold. For foreign nationals with irregular migration status, there is state medical aid (Aide médicale de l’État, AME), which provides minimal protection with a reduced range of care and services.

Only the child protection system (Aide Sociale à l’Enfance, ASE) or the juvenile justice department (Direction de la protection judiciaire de la jeunesse, DPJJ) can unlock the right to PUMa and C2S for unaccompanied migrant children.[94] Since formal recognition as a child is the first step to entry into the child protection system, youth whose minority is not formally recognized—according to a 2011 joint ministerial circular, those “without any ties, without support from any structure”—can thus only benefit from state medical aid (AME).[95]

Under French law, children cannot technically be considered irregular because they are not obliged to present a residence permit (titre de séjour).[96] According to MSF France’s advocacy manager, Euphrasie Kalolwa, classifying an unaccompanied child who is not formally recognized as such as irregular is contrary to their rights:

It’s a way for the administration to reinforce [its view that] that the young person is of legal age. When you sleep in an adult shelter, when you only have access to state medical aid intended for irregular migrants above the age of 18 ... [the only] elements that you could put on the table to show your administrative social situation will indicate that you are of legal age.[97]

Domiciliation and Three-Month Waiting Period

Access to AME is subject to obtaining a residence address (domiciliation) where an individual can receive mail. For adults with irregular migration status, it is possible to obtain such an address from a local social welfare center (Centre communal d’action sociale, CCAS) or a domiciliation agency (organisme domiciliataire). However, these centers generally refuse to register children without formal documentation proving recognition or refusal of their minority, meaning that unaccompanied children still in the temporary emergency accommodation (APU) period are left without the possibility of accessing this option.

To access AME, individuals must also be able to justify three months of residence on French territory.[98] Per a 2011 joint ministerial circular, unaccompanied migrant children are exempt from this requirement.[99] However, departments do not always follow the rule set forth in the circular, according to volunteers. As a result, it can be complicated for children who are waiting for age assessments or who have not been formally recognized as children to gain access to health coverage. This is a problem across many French departments, including Marseille: in 2022, 97.1 percent of unaccompanied migrant children who visited over a dozen Médecins du Monde health centers across the country were not covered by any type of health insurance.[100]

State Medical Aid Through ADDAP 13

In Marseille, through an agreement with the local social welfare center, unaccompanied migrant children whose minority has been recognized can obtain domiciliation, and subsequent access to state medical aid (AME), through Médecins du Monde or a hospital-based medical center for individuals without health care coverage (Permanence ď Accès aux Soins de Santé, PASS).[101] However, volunteers and doctors told Human Rights Watch that social workers at ADDAP 13 do not help file the necessary documents to open the right to AME for these children. A doctor explained:

These kids are often not autonomous enough to take the steps needed to file the documentation for AME and they need a social worker to help … but neither the department’s social workers nor those at ADDAP 13 do it. We do it at PASS, and the social services at the hospital also do it, but for kids who don’t visit us or the hospital, they don’t have access to this right.[102]ADDAP 13 told Human Rights Watch, “If the need for care is immediate, the medical staff will initiate a request for state medical aid (AME). For young people with an OPP [a provisional placement order] or for those benefitting from an administrative placement measure, AME is available.”[103]

Legal Representation

Under the French public health code, minors are required to obtain consent from a parent or legal representative for certain medical procedures.[104] While unaccompanied migrant children cannot meet this prerequisite by nature of their circumstances, there are exceptions to the rule for all minors in France. Children above age 16 who are granted the right to PUMa and C2S health coverage through the child protection system are considered exempt from the obligation to obtain legal authorization from a parent or legal guardian and thus have complete autonomy over their health decisions.[105] However, children who are not formally recognized as minors and who can only benefit from state medical aid (AME) do not benefit from this exemption and cannot obtain the necessary legal authorization.

Lucie Borel of Médecins du Monde Marseille told Human Rights Watch, “While a child may not be recognized as a minor by the department, in every other aspect of the French system, they are considered as such. [For example] … to get an operation, they need parental consent.”[106] Medical professionals in Marseille described cases of children who were not granted authorization for medical procedures because they did not have a legal representative. Dr. Rémi Laporte, a pediatrician in Marseille who treats unaccompanied migrant children at a hospital-based medical center (Permanence ď Accès aux Soins de Santé, PASS) for patients without health care coverage, remarked that delaying non-urgent procedures until children reach the age of majority can result in complications:

If the child needs an urgent medical operation, the anesthesiologist will generally comply, but if it’s not urgent and there is no legal representative to provide authorization, the anesthesiologist will refuse … and the juvenile judge usually won’t reply if we ask for authorization … so for children who need non-urgent medical interventions, it’s difficult to receive a reply from the judge.[107]Even if medical procedures and other health care are not strictly urgent, delays of several months or more can have adverse health consequences, as discussed more fully in the following section.

Negative Health Outcomes

Unaccompanied migrant children often arrive in France after experiencing harms in their home countries; dangerous and arduous migratory journeys; ill treatment, forced labor without pay, and arbitrary detention in inhumane conditions by unidentified groups in Libya; and border crossings that put them at risk of violence.[108] Upon reaching Marseille, most of these children are in vulnerable states of physical and mental health and may lack access to appropriate services.

While ADDAP 13 is responsible for performing an initial health assessment once youth enter the temporary emergency accommodation (APU) period and advised us that “[e]very young person is received by a nurse on the day of his or her admission [into APU] and receives a medical examination,”[109] our research found that these assessments are not systematically performed. As a result, children who experience unmet health needs and are denied recognition of their age may be returned to the streets without treatment, psychosocial support, or follow-up care.

Physical Health

According to Médecins du Monde, nearly half of all unaccompanied migrant children who visited their national health centers in 2021 were diagnosed with a chronic health condition, defined broadly as a condition that is long-lasting, and nearly three out of five with an acute pathology, a condition that usually begins abruptly and has a short course.[110] This is consistent with observations from Laporte:

I see a lot of traumatology, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and psychological issues from the journey. There are very few kids migrating with their families who have HIV, STIs, or hepatitis … yet I see many cases of those pathologies within the MNA [unaccompanied migrant children] community, owing to the risks they face because they are unaccompanied.[111]Another doctor treating unaccompanied children in Marseille told Human Rights Watch that upon reaching France, children are often chronically exhausted and their condition worsens due to difficulty accessing their primary needs. “Precarious living conditions are dangerous for the physical integrity of unaccompanied minors and sometimes lead to hospitalizations lasting several days, which could be avoided.”[112]

Mental Health

Social workers, psychologists, and doctors treating unaccompanied migrant children in Marseille reported a high incidence of symptoms such as intrusive thoughts consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder, sleep difficulties, depression, and anxiety. While some children Human Rights Watch spoke with were able to explain what they were feeling, most did not have the technical vocabulary or emotional capacity to describe in detail their experiences or what they needed to recover.

Trauma from the Journey

The trauma unaccompanied children experience before, during, and after their journey to France is likely to be significant, psychologists and social workers suggested. This is consistent with previous research by Human Rights Watch documenting the mental health crisis among individuals seeking refuge in the European Union.[113] Moreover, according to Marie Jacob, psychologist at Le Comede, “The secondary effects of trauma from a voyage by boat appear markedly greater on children than on adults.”[114] Post-traumatic stress, linked to threatening, harmful, and potentially traumatic events, impacts children’s ability to recount their personal history and express themselves.[115] This has implications for age assessments where examiners ask youth questions about their migratory journey, family background, and reasons for leaving the country of origin, all the while judging their ability to remember subtleties. A psychologist treating migrant children in Marseille explained, “The process of recounting painful and violent memories reactivates post-traumatic stress…. It forces children to relive past terrors as if they are happening in the present moment.”[116] Social workers and volunteers told Human Rights Watch that the overwhelming majority of unaccompanied migrant children who arrive in Marseille have experienced some kind of trauma. “All of these kids have either escaped death or lost someone on the way here,” a Collectif 113 volunteer said.[117]Interviews with children, and anyone who may have experienced trauma, require expertise and care to avoid retraumatization. However, according to volunteers in Marseille, age assessments do not always tailor to the child’s mental health state or needs and often compound anxiety and trauma. Staff from Project ASSAb told us:

We see many children arriving with considerable psychological traumas from their migratory journey, kids who are not even able to recount their story because they’re too submerged, but the evaluation is done anyway. And if the result is negative, the child is put on the street immediately, even if he or she is completely overwhelmed.[118]Though emotional avoidance and memory loss are known to be two common defense mechanisms in individuals with trauma, examiners at ADDAP 13 often take these as signs of adulthood.[119] As described by Lawyers from the Unaccompanied Minors Commission of the Marseille Bar Association, “Often times we see written down on age evaluations that the child recounted the loss of a loved one along the journey with ‘emotional detachment’ and that’s a reason to not believe their age.”[120] Another generic justification for a negative age assessment on case files viewed by Human Rights Watch was “short-term memory problems.”

The fact that age assessments are conducted without taking into consideration children’s psychological vulnerability “constitutes an abuse of sorts,” said Julien Delozanne, of MSF Marseille.[121]

In response to our request for comment, ADDAP 13 wrote:

With regard to the assessment interview and the person's state of health, as indicated in the section on the assessment, before any interview date is set, a review is carried out with the educational and medical team. If the professionals in charge of the young person report a situation of significant trauma, deficiencies, or a state of health too degraded to allow the exchange to proceed smoothly, the interview will be postponed and the Departmental Council informed. If necessary, an extension may be requested, and the person may continue to receive shelter.[122]

Protracted Periods of Uncertainty

Our research found that the age assessment procedure and the ensuing lengthy periods of uncertainty and instability for children deemed adults heighten feelings of depression, anxiety, and self-harm.[123] In a typical account, Moussa E., a 17-year-old boy from Guinea determined to be an adult after a flawed age assessment, told us, “I love music and football. But I don’t find joy in these things anymore because I’m waiting endlessly. I’ve had a lot of problems with my passport and with getting my documents. All my energy is spent waiting.”[124]

After spending months to years on the move, the added stress associated with being rejected upon arrival in France has a detrimental effect on unaccompanied children’s mental health. MSF psychologist Julie Arçuby told Human Rights Watch that uncertainty regarding accommodation and the length and eventual outcome of judicial proceedings not only exacerbates existing mental health conditions but also causes new psychological distress:

I know kids who have already slept in ten beds since arriving in France, who aren’t yet recognized as minors and aren’t even at the end of their journey. The consequence of this insecurity on their mental health is enormous. The uncertainty exacerbates existing traumas, such as those linked to what happened in their home country, or the horrors they encountered on their journey to France.[125]

Ibrahima N., a 16-year-old boy from Guinea, told us, “France was my dreamland but now that I am here, there are too many worries. I am always thinking about what will happen next. I really thought I would be accepted here … I didn’t think it would be this hard.”[126]

Most children we interviewed told us they were deeply distressed awaiting the outcome of judicial hearings to review negative age assessment determinations. “My lawyer told me I’ll finally go to the judge next month, after one full year in France, but I don’t know what will happen. I’m losing time,” Syed A., a 17-year-old Bangladeshi boy, said.[127] In a similar case, Salimatou A., a 17-year-old boy from Guinea, told us, “I have a lawyer. I send her messages, but she can’t always reply. I am stressed when people tell me it will take more time. It’s been a year and nothing. I continue waiting.”[128]

Kwame B., a 15-year-old Ghanaian boy who, with the aid of lawyers, asked the juvenile judge to review his negative age assessment, told us in May 2023, “When my passport comes back, I will see the judge again. But it’s been eight months and I’m still waiting. I stopped calling my lawyer because when I do, I start to cry.”[129] When we spoke to him again at the end of June, he still had no word on when he would hear the outcome of his case.[130]

A psychologist providing psychosocial support to unaccompanied migrant children told us that “[t]he perpetual uncertainty that these children experience—the anxiety of the arrival of their 18th birthday and not knowing what might happen in the future—sustains their state of serious stress and depression.”[131]

Navigating the complexities of the French system is also especially bewildering for children and weighs on their mental health. “The law is often impossible to understand. It’s done on purpose … it’s a way, like others, of refusing the reception of migrant children on our territory,” a doctor treating youth in Marseille told Human Rights Watch.[132]Initial Health Screening

Under French law, the department is responsible for carrying out “an initial assessment of the health needs of people presenting themselves as minors and temporarily or permanently deprived of the protection of their family… and, if necessary, an orientation for care.”[133] The French Defender of Rights (Défenseur des droits) also advocates for unaccompanied individuals declaring themselves to be under age 18 to undergo a health check during the temporary emergency accommodation (APU) period.[134]