(New York) – A database obtained by Human Rights Watch supports findings of mass due process violations, severe prison overcrowding, and deaths in custody in El Salvador, Human Rights Watch and Cristosal said today.

The database appears to belong to the Ministry of Public Safety and lists names of people prosecuted between March and late-August 2022 during the country’s state of emergency. It indicates that thousands of people, including hundreds of children, have been arrested and charged with broadly defined crimes that violate detainees’ basic due process guarantees and undermine prospects of justice for victims of gang violence. The document also supports Human Rights Watch and Cristosal’s findings of severe overcrowding conditions in detention and deaths in custody.

“This leaked database points to serious human rights violations committed during the state of emergency,” said Tamara Taraciuk Broner, acting Americas director at Human Rights Watch. “According to the data, Salvadoran authorities have inhumanely packed detainees, including hundreds of children, in crowded detention sites, while doing very little to ensure victims’ access to justice for gang violence.”

In March 2022, the Salvadoran Legislative Assembly passed a state of emergency, suspending some fundamental rights in response to a peak in gang violence. The measure has been extended 10 times and remains in place. Police officers and soldiers have detained over 61,000 people since March, according to the authorities. About 3,000 people have been released, in many cases under parole, and 58,000 remain in prison.

The database provides the names, ages, and gender of people prosecuted under the state of emergency between March and August 2022. It also contains information about the charges against detainees, and the city where they were arrested.

A reliable source indicated that the database belongs to the Public Safety Ministry. To assess its authenticity, Human Rights Watch cross-referenced the names in the database with other sources, including cases documented by local organizations or reported in the media, and identified over 300 matches. Other information presented in the database, including the crimes attributed to many of the detainees, the detention facilities where they were often sent, and the total number of people in pre-trial detention, are consistent with Human Rights Watch and Cristosal’s findings and with information publicly reported by government authorities.

The following information in the database raises serious human rights concerns:

- As of late August, 1,082 children arrested during the state of emergency – 918 boys and 164 girls – had been sent to pre-trial detention, including 21 who were ages 12 or 13. These incarcerations were made possible under a March 2022 law that lowered from 16 to 12 the age of criminal responsibility for children accused of gang related crimes.

- The database indicates that 32 people died in custody, most of them at the La Esperanza, also known as Mariona, and Izalco prisons. Salvadoran authorities reported in November that 90 people have died in custody since March, in circumstances that have yet to be properly investigated.

- Over 39,000 people had been charged with the crime of “unlawful association” and over 8,000 with membership to a “terrorist organization.” In comparison, many fewer people had been charged with violent crimes. 148 people, or less than 0.3 percent of the detainees, were charged with homicide and 303 people, or less than 0.6 percent, were charged with sexual assault. El Salvador defines the crime of “unlawful association” broadly to include not only people who lead or take part on gangs, but also those who receive “indirect benefit” from gangs by having relations “of any nature.” Salvadoran law also defines “terrorist organization” in a broad manner that runs counter to international standards. The use of these broadly defined crimes opens the door to arbitrary arrests of people with no relevant connection to gangs, and does little to ensure justice for violent gang abuses, such as killings and rape.

- As of August, over 50,000 people had been sent to pre-trial detention, increasing the prison population to over 86,000. According to public information, as of February 2021, prisons in El Salvador had capacity of 30,000. Those sent to pre-trial detention since the adoption of the state of emergency include over 7,900 women, double the total number in jail in El Salvador as of February 2021.

- Most of the detainees were sent to Mariona prison, where the population increased from 7,600 from 33,000, and to the Izalco prison, where the population increased from 8,500 to 23,300. According to the database, as of August, Mariona had four times as many detainees as it could hold, and Izalco had three times as many. Other detention facilities, such as the Ilopango prison for women and the prison of San Miguel for men, had populations of six times capacity. In October, the head of the prison system, Osiris Luna Meza, said that the women detained in Ilopango had been transferred to another prison.

A December 2022 report by Human Rights Watch and Cristosal found widespread human rights violations committed under the state of emergency, including mass arbitrary detention, torture and other forms of ill-treatment against detainees, deaths in custody, and abuse-ridden prosecutions. In some cases, officers also refused to provide information about the detainees’ whereabouts to their relatives and acquaintances, in what amounts to enforced disappearances under international law.

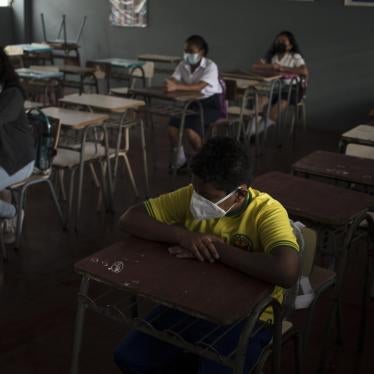

Security forces have carried out hundreds of indiscriminate raids, particularly in low-income neighborhoods, targeting marginalized communities where people have, for years, suffered from lack of economic and educational opportunities. The mass arrests have led to the detention of hundreds of people with no apparent connections to gangs’ abusive activity.

The abuses committed during the state of emergency have been enabled by President Bukele’s swift dismantling of democratic institutions since taking office in 2019, which has left virtually no independent government bodies that can serve as a check on the executive branch or ensure redress for victims of abuse.

The government has also restricted access to public information and weakened the role of the Access to Public Information Agency. The authorities told Human Rights Watch and Cristosal that information about people detained during the state of emergency is “classified,” even when it is of public interest under international human rights standards.

Salvadoran authorities should replace the state of emergency with a sustainable and rights-respecting strategy to address gang violence and protect the population from gang abuses, Human Rights Watch and Cristosal said. The strategy should include tackling high levels of poverty and social exclusion, and focusing on prosecutions of higher-level gang leaders.

“These new findings support the conclusions of our reports on widespread human rights violations, which are especially serious in a context of lack of accountability and massive due process violations. We urge governments in the region to guarantee public security without engaging in unfair policies,” said Noah Bullock, executive director of Cristosal.