It was freedom Ali sought when he fled to Canada for refugee protection, having escaped his home country in North Africa where he faced persecution for his political and social justice activism. But he spent his first days and nights in Canada in immigration detention. Ali was placed in a solitary confinement cell of the Central Nova Scotia Correctional Facility at Burnside, a maximum-security provincial jail. “The border officers took my photo and fingerprints, and said they want to know everything about me since I was born. I answered all their questions,” he told me. “Then they took me to jail without any charge. They didn’t tell me why. And they didn’t say how long I would stay there.”

Ali arrived on a cargo ship that sailed across the Atlantic. He said it was the only way he could reach Canada to make a refugee claim. He spent nine days in the fetal position, eating only dates and nuts, hiding in the trunk of a car onboard the ship. Once he ran out of water, he had no choice but to present himself to the ship’s crew. “It was cold there because we were crossing in early spring. All my joints were in severe pain,” he said. “I was scared the crew members might throw me overboard the ship because I heard the shipping company gets fined if refugees make it across.”

Ali was prepared for the perilous trip, but he was shocked to be incarcerated upon reaching Canadian shores in Nova Scotia. “It was a nightmare,” he said. “In jail, the first thing they told me to do was strip.” He said he removed his clothes but asked the guards to let him keep his underwear on. “They refused. It was humiliating, especially because there was a camera in the room. They didn’t tell me why this was necessary.”

Then, with his bright orange jumpsuit on, Ali was placed in solitary confinement. He described it as a “small room with a concrete bed with a thin mattress, and a small toilet in the corner. You could take about two or three steps from wall to wall.” He told me guards would bring food three times a day, and if he was awake, they would pass it through a narrow latch in the metal door. Some sounds and images have stay with him: “In the morning, a guard would knock aggressively on the metal door with his baton to wake me. During the night, guards would open the latch and peak in with their flashlights, shining light in my eyes.” There was no window, no natural light. “I was trying to relax and stop thinking, but I didn’t know how to control my mind to avoid getting depressed,” he said. “I tried to avoid thinking that I might stay in jail forever. I was scared they would send me back home, where I would be targeted. I didn’t know what was going to happen to me.” Ali said he was in severe pain from his journey across the ocean and asked to see a doctor. But he was only given painkillers.

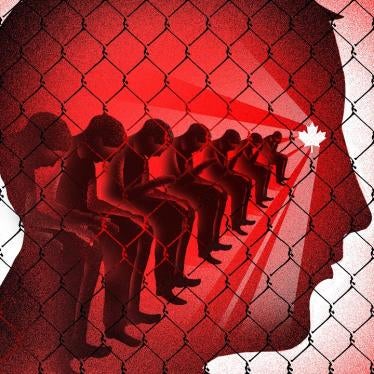

Ali is one of tens of thousands of people who have been incarcerated in immigration detention in Canada over the past decade – people who come to Canada seeking safety or a better life. None are held on criminal charges or convictions, but many endure the country’s most restrictive jail conditions. In seven of the ten provinces, including Nova Scotia, immigration detainees are incarcerated in provincial jails by default because there are no dedicated federal facilities for immigration detention. Canada is among the only countries in the global north without a legislative limit on the duration of immigration detention, and as a result, many languish in confinement with no end in sight.

After several days in jail, Ali was finally connected with a legal representative from the Halifax Refugee Clinic, who helped him obtain a release order about a week later. He pursued his refugee claim and began working as soon as he received a work permit. In 2020, Ali started working at a North African restaurant. “It feels like home,” he told me. “I cook and serve tables; I cover whatever need arises.” After waiting several years for his refugee hearing, Ali was finally granted refugee protection. With his newfound freedom, he set out across Canada.

Along the way, Ali used an app to connect with other cyclists, who hosted him in their homes, offering a warm place to sleep for a night or two. “The best part of the trip was the people I met,” he told me. “Hearing different stories opens your mind to more ways to see Canada. You get a chance to learn and hear from locals.” Ali asked each person he met to sign his notebook and share a piece of advice. He told me sometimes he doubted whether he could finish his journey across the country, but the most memorable piece of advice he received encouraged him to persist: “we are like the universe, we are limitless. We are always expanding, so push yourself to do more. Don’t limit yourself. If you can cycle 5 kilometers, you can cycle 500 kilometers. It’s just a matter of time.”

On the other side of the country, in British Columbia, Ali came upon a statue of Terry Fox, a Canadian athlete, humanitarian, and cancer research activist who had one leg amputated due to cancer. In 1980, Terry Fox embarked on a cross-Canada run to raise funds and awareness for cancer research, running over 5000 kilometers in 143 days. The plaque beneath the statute read, “Somewhere the hurting must stop.” These words deeply resonated with Ali.

“I will never forget my first days in Canada,” Ali told me. “I was shocked, scared, and exhausted. Being surrounded by walls, I just wished I could see the moon.” But cycling across Canada was healing for Ali: “In some parts of the country, you see no limit – only land and sky. It was beautiful. I saw freedom,” Ali said. “I did this trip to heal from the past. To be closer to nature. To connect and reflect, and to get to know this country.”

Incredibly, it was during Ali’s cross-country trip that the provincial government of Nova Scotia finally came to the decision that people who come to Canada to seek safety or a better life should no longer be incarcerated in provincial jails on immigration grounds. The provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, and Manitoba made the same determination. When I asked Ali what he would say to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau about immigration detention, if given the chance, he smiled gently and looked down at his hands, and said, “There is already so much trauma, there is no need to add more. These first interactions [with authorities] stay with you forever.”

It’s high time for the Prime Minister to show leadership and finally put an end to the human rights violations taking place in Canada’s immigration detention system. The federal government has the power to put an end to this abuse. Stopping the use of provincial jails to incarcerate people seeking safety or a better life – people for whom Canada represents hope and a home – is a good place to start.