Russia is a country where thousands are detained at peaceful demonstrations and even single-person picketers are thrown behind bars — all in the name of public safety and even public health.

In this country however, there is one city where up to four hundred thousand people can gather for a “spontaneous rally,” shout for violence, even make a bonfire of posters with photos of “enemies of the people” — and suffer no consequences.

This city is Grozny, Chechnya’s capital. It happened on Feb. 2. Only that the rally was very far from spontaneous.

For many years, the local governor, Ramzan Kadyrov, has been ruling over Chechnya with an iron fist.

Central to his rule is the principle of collective punishment, whereby entire families pay the price for the words or alleged deeds of those who oppose Kadyrov, from armed insurgents to peaceful critics.

Law enforcement agencies under his de-facto control forcibly disappear, torture and kill — and those who dare speak up about abuses are ruthlessly punished and forced to recant on state television. But Moscow turns a blind eye.

Using these tactics, the local authorities have largely succeeded in beating residents of Chechnya into silence.

But they find it more difficult to ensure the subservience of Chechens who fled the republic for Europe, Turkey or the Middle East.

Critical voices from the Chechen diaspora — both peaceful and radical — have grown louder and more consolidated.

Antagonized by these voices, in December, Kadyrov opened a brutal offensive against them.

In Chechnya, the law enforcement and security officers under his control arbitrarily detained dozens of relatives of Kadyrov’s opponents, held them for days, and subjected them to ill-treatment.

These included family members of two opposition bloggers, Tumsu Abdurakhmanov and Khasan Khalitov. Most of the family members were eventually released but some are still forcibly disappeared.

On Jan. 24, Khalitov told the media that his sister and brother-in-law remained disappeared and that he had received anonymous messages threatening sexual violence against his sister.

One of the key targets of this lawless campaign is 1ADAT, an anti-Kadyrov social media channel, which was created in 2020 and gradually gained popularity, especially among disaffected youth.

On Jan. 20, Chechen police seized Zarema Mussaeva, the mother of 1ADAT’s supposed administrator, Ibrahim Yangulbaev.

They dragged Mussaeva to their vehicle, barefoot through the snow, without so much as letting her get her insulin, on which she depends to treat her diabetes. They drove her 1,800 kilometers from Russia’s Volga region all the way to Chechnya at top speed with no rest stops. For two weeks, they held her incommunicado.

When Mussaeva’s lawyers were finally allowed to see her, the authorities had opened a criminal investigation against her alleging she had attacked and scratched a police officer.

Mussaeva remains a hostage, but Chechen authorities have not achieved what they no doubt hoped to by seizing her – the rest of the family did not come to Grozny to grovel and publicly debase themselves.

Instead, her husband and children are now all outside of Russia and demanding her release. In response Kadyrov publicly called them “terrorists,” accused them of “trampl[ing] on [Sufi] Islam, promised they would be found and destroyed, and threatened that any country hiding them will see nothing but “trouble.”

He also branded as “terrorists” an investigative reporter, Elena Milashina, and a prominent human rights defender, Igor Kalyapin over their efforts to protect the Yangulbaevs from reprisals.

In case anyone doubted the sincerity of his threat, Kadyrov emphasized that Chechen authorities “always destroyed terrorists and their accomplices, between whom there is no difference, and we will continue to do so."

One of Kadyrov’s closest associates, Adam Delimkhanov, who is also a member of the Russian parliament, recorded an impassioned video, declaring a blood feud on the Yangulbaev family and pledging to tear their heads off. These are far from empty threats, given the numerous failed and successful assassination attempts against Kadyrov’s opponents in other countries, most recently in Germany, Sweden, France, and Austria.

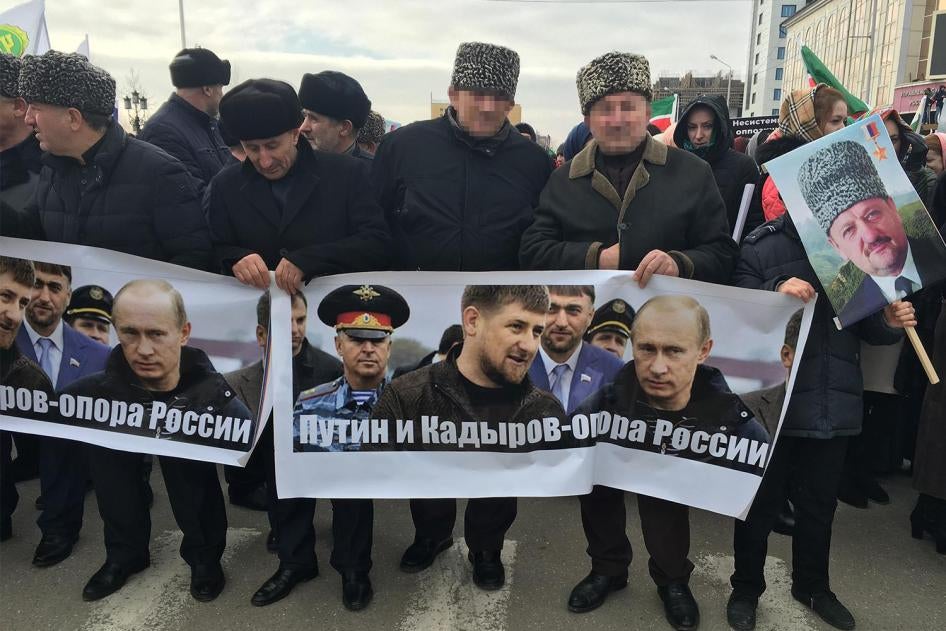

To reinforce this message, Chechen authorities orchestrated the Feb. 2 massive rally of hatred in Grozny, when half of Chechnya’s adult male population, if one is to believe official sources, came together to condemn the Yangulbaevs, beat their portraits with sticks and burn them.

Moscow has never publicly called Kadyrov to task and the outrageous onslaught on the Yangulbaev family hasn’t elicited an exception.

When asked by journalists to comment, President Vladimir Putin’s press secretary said that Kadyrov was expressing his “personal opinion” and the Kremlin saw no reason to intervene. As for the rabid “blood feud” declaration by Delimkhanov, he suggested that since Delimkhanov is a member of parliament, it’s up to the parliamentary commission on ethnics, rather than the Kremlin, to look into his actions.

However, the growing media outcry and the grotesque images from the rally in Grozny apparently did not leave the Russian leadership indifferent.

On Feb. 3, Putin met with Kadyrov in Moscow. According to official reports, they discussed a range of issues regarding the region’s economic development, healthcare system, and law enforcement.

Although no details or criticism were publicly released, one can’t help recall the last time Putin summoned Kadyrov to Moscow was in spring 2017, during the anti-gay purge in Chechnya, which made international headlines.

Back then the “on record” conversation also largely revolved around economic issues and social welfare, but in the middle of that rather routine conversation Kadyrov suddenly mentioned “provocative articles about the Chechen Republic, the supposed events…” — in other words the purge — which he then vehemently denied.

Putin said nothing in response. Kadyrov returned to Grozny, the purge was suspended, and Chechen authorities did not actively interfere with the survivors fleeing.

It seems that when Grozny’s egregious lawlessness develops into a particularly loud and disgraceful scandal that attracts international attention, Putin can quietly tell Kadyrov to slow down. From that perspective, last week’s sudden meeting between Putin and Kadyrov gives hope of a de-escalation in Grozny’s war against critics.

However, that de-escalation is unlikely to be anything but temporary. With absolute impunity for the 2017 anti-gay purge, in another 18 months local police authorities started a new round of unlawful detentions and torture of men they presumed to be gay or bisexual.

Moscow should stop simply whispering in Kadyrov’s ear behind a close door, but take the forceful and unambiguous action it is obliged to, and demonstrate that lawlessness will no longer be tolerated.

That means, at minimum, ensuring Zarema Musaeva’s immediate release and launching investigations into Chechen officials’ public threats against the Yangulbaevs and other critics.