- Who are Anwar R. and Eyad A.?

- What are the charges against the two defendants?

- Are the charges against the defendants representative of crimes committed in Syria?

- How did allegations against Anwar R. and Eyad A. specifically come to the attention of German authorities?

- What rights do the defendants have at trial, and have they been detained during the trial?

- What did Anwar R. and Eyad A. say in their defense?

- Can the judgments be appealed?

- What is universal jurisdiction and how does universal jurisdiction work in Germany?

- How did German authorities come to investigate serious crimes in Syria?

- Why is the International Criminal Court (ICC) not investigating crimes in Syria?

- How are survivors involved in the trial?

- What did the trial reveal about torture in Branch 251?

- What role did the Caesar photos play in the trial?

- Have witnesses faced challenges in testifying in the Koblenz trial?

- Have German authorities taken steps to make the trial accessible to communities affected by the crimes charged and the general public?

- Have the German judicial authorities conducted any outreach on the trial?

- Are there any other proceedings in Germany against Syrian officials or other parties to the Syrian conflict known to have committed abuses?

- Could Bashar al-Assad, Syria’s head of state, or other high-level officials be prosecuted under universal jurisdiction laws?

- Is there any option for further accountability for serious crimes committed in Syria?

In April 2020 a German court in the city of Koblenz began hearings in the trial of Anwar R. and Eyad A., both alleged to be former Syrian intelligence officials, on crimes against humanity charges. This trial, the first anywhere in the world for state-sponsored torture in Syria, is a watershed event for torture survivors and international justice. The issues at stake offer a snapshot of what happened in Syria between 2011 and 2012, and the case has afforded victims an otherwise elusive chance to see at least some justice done.

Human Rights Watch has been monitoring the trial in-person since the beginning, with the help of the Frankfurt office of the law firm Clifford Chance. This question-and-answer document provides some background to the trial, the accused, and overall efforts by Germany to investigate and prosecute serious crimes under international law before its national courts. This trial is possible because of Germany’s universal jurisdiction laws, allowing for the investigation and prosecution of certain of the most serious crimes no matter where they were committed and regardless of the nationality of the suspects or victims.

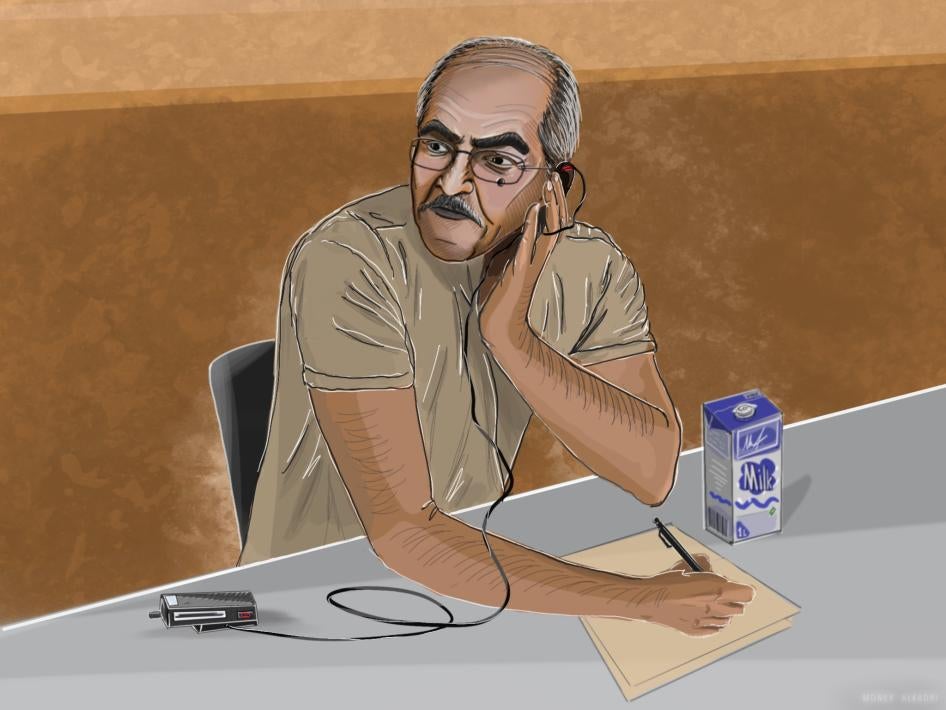

Anwar R. is alleged to be a former intelligence officer in Syria’s General Intelligence Directorate, one of the country’s four main intelligence agencies commonly referred to collectively as the mukhabarat.

Anwar R. is the most senior alleged former Syrian government official to be put on trial in Europe for serious crimes committed in Syria, although as a colonel he would be considered a relatively low-ranking official within the overall context of the Syrian intelligence services. German prosecutors accuse him of overseeing the torture of detainees in his alleged capacity as head of the investigations section at the General Intelligence Directorate’s al-Khatib detention facility in Damascus, also known as “Branch 251.” The verdict against Anwar R. is expected to be issued in January 2022.

The prosecution and several witnesses say that Anwar R. was a lawyer by training who joined the intelligence services in the 1990s and worked for “Branch 285,” another detention facility of the Intelligence Directorate. Evidence introduced at trial indicates he became the head of the investigations department (Branch 251) in January 2011. Anwar R. does not deny working for the Syrian intelligence services but denies ever overseeing torture while he was there.

Eyad A. is lower in rank and was convicted on February 24, 2021, of aiding and abetting crimes against humanity, and sentenced to four years and six months in prison. Eyad A.’s defense counsel have appealed the conviction. The appeal is pending. The court found that Eyad A. was employed in division 40, a subdivision of Branch 251, which assisted the investigation unit Anwar R. is alleged to have headed.

The court found that Eyad A. worked for the Syrian General Intelligence Directorate for 16 years, from July 10, 1996, to January 5, 2012. The court concluded that in September/October 2011 he assisted in transporting 30 protesters in Douma to Branch 251, where they were later tortured. In their closing statements, his lawyers requested his acquittal, contending that their client had no choice to leave his position earlier without risking his and his family’s life, and thus acting out of necessity.

Information provided to German authorities indicates the men defected from the Syrian government in 2012. German authorities said that Anwar R. and Eyad A. entered Germany as asylum seekers in July 2014 and April 2018, respectively.

Prosecutors allege that between April 2011 and early September 2012, Anwar R. oversaw the torture of at least 4,000 people during interrogations, 58 murders, and deprivation of liberty and cases of rape and sexual assault at Branch 251. Following a motion to the court by victims’ lawyers, the crimes of rape and sexual assault were prosecuted as crimes against humanity charges instead of isolated acts under German criminal law.

In addition, in July 2021, victims’ lawyers supported by the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) filed a second motion to the court to update the charges against Anwar R. to include the crime of enforced disappearance.

German prosecutors asked the court to impose a life sentence in their closing statements on December 2, 2021. Under German law, a life sentence means imprisonment for an indefinite period of time with the possibility of parole after 15 years.

In the case of Eyad A., prosecutors alleged that he detained 30 protesters in 2011 and delivered them to Branch 251, where they were tortured. Eyad A. was charged with aiding and abetting serious crimes, and Anwar R. was prosecuted as a perpetrator.

The cases against Anwar R. and Eyad A. deal with crimes committed in Branch 251, also referred to as “al-Khatib” prison, in Damascus. Based on testimony provided at the trial, the prison is a two-building complex, containing both prison cells and interrogation rooms. Human Rights Watch research dating back to 2012 documented four cases of torture and mistreatment in Branch 251.

Since the beginning of anti-government protests in March 2011, Syrian authorities have arbitrarily arrested, unlawfully detained, forcibly disappeared, and tortured tens of thousands of people. The worst abuse and torture took place in an extensive network of detention facilities under the control of the Syrian government’s intelligence agencies.

The Syrian government continues to detain and forcibly disappear tens of thousands of people. Their families are rarely told where their loved ones are held or whether they are still alive. According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), at least 100,000 Syrians remain forcibly disappeared. The network also estimates that nearly 15,000 have been tortured to death since March 2011, the majority at the hands of Syrian government forces.

- How did allegations against Anwar R. and Eyad A. specifically come to the attention of German authorities?

Anwar R.’s and Eyad A.’s own statements given to German authorities triggered investigations against them.

Usually, German migration authorities (Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, BAMF) are one of the first contact points for Syrian asylum seekers arriving in the country and the first to conduct interviews with them. As a result, these are often the first German authorities to receive information about whether Syrian asylum seekers have witnessed serious crimes. German criminal procedure and asylum law regulate the exchange of information between the migration authority and the police.

If during an asylum interview an immigration case worker comes across information relevant to crimes under the Code of Crimes Against International Law (CCAIL), they send it to a special division at the BAMF. The CCAIL defines war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide in accordance with the treaty of the International Criminal Court (ICC), and also incorporates provisions on command responsibility, among other modes of liability. The specialized division then shares such information with the federal criminal police, which analyzes it and may send specific follow-up inquiries before sending the case to the war crimes prosecution unit for further action.

This is what happened in the case of Eyad A.. According to asylum authority employees and police investigators who testified in Koblenz, during a hearing in Eyad A.’s asylum proceedings, he revealed his activity within the secret service, but initially in May 2018, he claimed to be a witness to violent assaults on protesters. However, during a police interrogation in August 2018, he disclosed his involvement in the arrest of 30 demonstrators in Douma, as well as their transfer to the prison of Branch 251, and he also admitted to witnessing their mistreatment. These statements triggered an investigation by the police.

As for Anwar R., police investigators testified that he filed a criminal complaint with a Berlin police station stating that he felt he was being followed by Syrian intelligence agency members in 2015. He gave information on his work as a Colonel in Syria’s General Intelligence Directorate. Based on this information, the federal police contacted prosecution authorities to open investigations.

In February 2019 the Federal Court of Justice issued two arrest warrants against the accused. They were arrested five days later and taken to pretrial detention.

Testimony from witnesses supported by ECCHR, the Syria Justice and Accountability Center (SJAC), the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, and other nongovernmental organizations also contributed to arrest warrants for Anwar R. and Eyad A..

In March 2019, as evidence linked Eyad A. to a sub-division of Branch 251, prosecutorial authorities combined his investigation with that of Anwar R., a police officer testified in court. According to police investigators, they interviewed over 70 witnesses including former detainees of branches 285 and 251.

Defendants in German criminal trials have rights to ensure a fair trial proceeding. These include (i) the right to be heard in court; (ii) the right to choose a defense lawyer at any stage of the proceedings; (iii) the right to be present at the main hearing; (iv) the right to file motions for evidence; (v) the right to summon witnesses and experts; (vi) the right to put questions to witnesses and experts; (vii) the right to appeal; (viii) the right to have an interpreter present free of charge if the accused does not speak German or does not speak it well enough; and (ix) the right to remain silent.

Anwar R. and Eyad A. are each represented by one public defender and one defender they personally chose. Public defenders are assigned by the court. The defendants’ lawyers are experienced specialists in criminal law and procedure.

Anwar R. and Eyad A. spent 15 months in pretrial detention before the trial started, on April 23, 2021. Anwar R. was detained in a prison in Koblenz during the trial, while Eyad A. was in a prison in Dietz, a town near Koblenz.

As defendants, Anwar R. and Eyad. A. are obliged to be at the main hearing. Under German law, however, the accused has the right to remain silent during the entire criminal proceeding. Neither defendant has made any verbal statements directly to the court. Anwar R. denied all accusations against him in a letter read out by his lawyers at the beginning of the trial, the Human Rights Watch trial monitors reported. In it he said that he was never involved in any form of torture at Branch 251 and rejected responsibility for the mistreatment there. Anwar R. commented on the testimony of certain trial witnesses and claimed either to not know them or denied that they were mistreated.

Eyad A., in a letter similarly read into the record by his lawyer, claimed that he had no other choice but to commit these crimes because of the security risks for his family. In the December 2020 letter, based on the Human Rights Watch trial monitoring, he said that the Caesar photos, entered into evidence by the prosecution, caused him distress. Many of the 53,275 Caesar photos smuggled out by a defector show the bodies of detainees who died in Syria’s detention centers. Eyad A. emphasized his early defection from the intelligence services despite the danger to him.

Eyad A.’s defense counsels challenged the admissibility of all of his statements made to police investigators prior to trial. They contended that the police investigators failed to properly inform Eyad A. of his rights as a suspect, in particular of his right to not incriminate himself when he was questioned in 2018. The Federal Court of Justice subsequently ruled that parts of Eyad A.’s statements were admissible, allowing the court to rely on some parts of his statements.

Yes. Under German law, the prosecution and the defendant can appeal judgments. Appeals are heard by the Federal Court of Justice. Eyad A.’s defense counsels appealed the judgment. The prosecution did not appeal for a longer sentence, even though they had requested one from the trial court. The appeal is pending.

Universal jurisdiction refers to legal frameworks that permit national judicial systems to investigate and prosecute certain crimes, even if they were not committed on the country’s territory, by one of its nationals, or against one of its nationals.

Some European countries, including Germany, France, and Sweden, are using universal jurisdiction laws to investigate allegations of serious crimes in Syria. While, in principle, it is preferable for justice to be carried out in the countries where the crimes are committed, this is often not possible. Universal jurisdiction reduces “safe havens” where those responsible for these crimes can find impunity and sends a strong signal about the nature and gravity of the underlying crimes.

Under the CCAIL, German authorities can investigate and prosecute grave international crimes committed abroad, even when these offenses have no specific link to Germany and investigations into these cases can proceed even if the suspect is not on their territory or a resident. The federal prosecution authority (“Generalbundesanwaltschaft”) and the federal criminal police (“Bundeskriminalamt”) are responsible for investigating and prosecuting serious crimes under the CCAIL.

However, this form of “pure” universal jurisdiction is tempered by certain procedural restrictions. For example, prosecutors have the discretion not to open an investigation for CCAIL crimes when no suspect is, or is expected to be, in Germany.

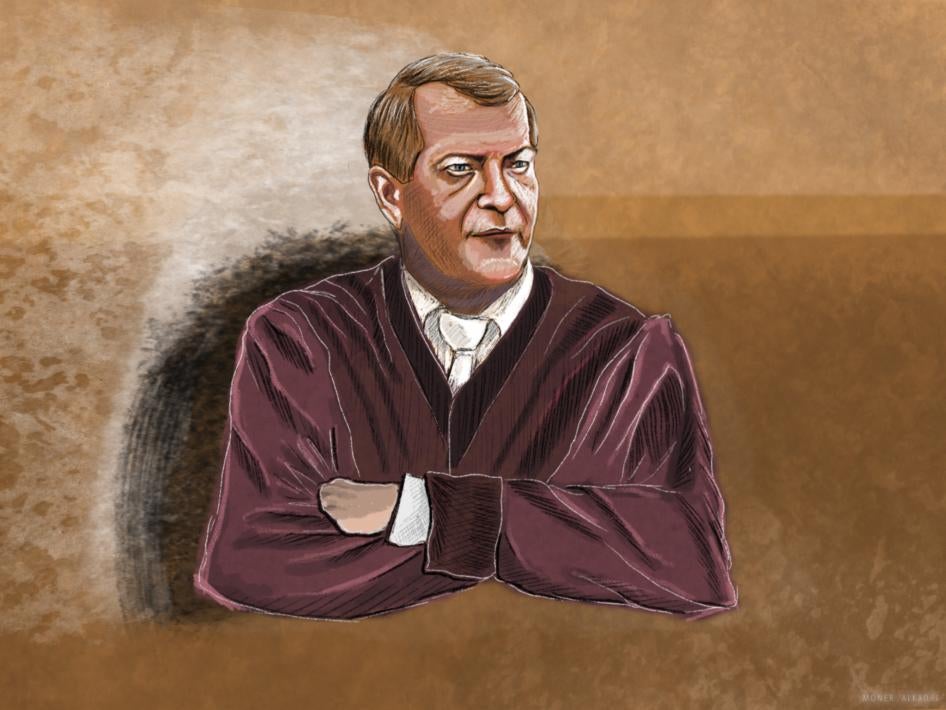

Trials are held before Higher Regional Courts (Oberlandesgericht). Higher Regional Courts in Germany deal with appeals from lower courts and so-called “state protection cases” that relate to serious crimes codified in the CCAIL. The chambers dealing with such cases are staffed with five judges. The language of the court is German. Defendants have the right to translation so that they can follow the proceeding. Decisions by the Higher Regional Court can be appealed to the Federal Court of Justice.

Beyond Syria, German courts have heard cases based on universal jurisdiction (at times together with other bases of jurisdiction) in relation to alleged crimes in countries including Iraq, Sri Lanka, and Rwanda.

German authorities were the first in Europe to open a “structural investigation” related to Syria. Structural investigations are broad preliminary investigations, which are not directed against specific individuals but instead attempt to catalogue crimes that have occurred in a particular country, gather details about them, and identify victims and witnesses in Germany for future criminal cases. In 2017 German prosecutors interviewed almost 200 witnesses in the two structural investigations relating to Syria.

The first structural investigation, initiated in September 2011, covers crimes committed by various parties to the Syrian conflict, but includes a particular focus on the “Caesar photographs.” The second structural investigation, initiated in August 2014, covers crimes committed by ISIS in both Syria and Iraq, with a focus on the ISIS attack on the Yezidi minority in Sinjar, Iraq, in August 2014.

The ICC cannot investigate crimes committed in Syria because the court has no jurisdiction. Syria is not a member state of the Rome Statute, the treaty that established the ICC. Unless the Syrian government ratifies the treaty or accepts the jurisdiction of the court through a declaration, the ICC could only obtain jurisdiction if the United Nations Security Council refers the situation there to the court. The Security Council, with what is called an “ICC referral,” could give the court jurisdiction stretching back to the day the Rome Statute entered into force, on July 1, 2002. In theory, the ICC would have jurisdiction over war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by nationals of ICC states parties anywhere in the world; but this would not include Syrian nationals.

In 2014, Russia and China blocked efforts at the United Nations Security Council to give the ICC a mandate over serious crimes in Syria. Two years later, UN member countries responded by setting up a new international mechanism to gather, analyze, and secure evidence of serious crimes for future prosecutions. The General Assembly created the mechanism, the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM), in an unprecedented December resolution. The mechanism’s work, along with other documentation efforts, will be critical to future domestic accountability processes in Germany and elsewhere. Police investigators testimony indicated that the trial in Koblenz is one of the cases that has grown out of this collective effort.

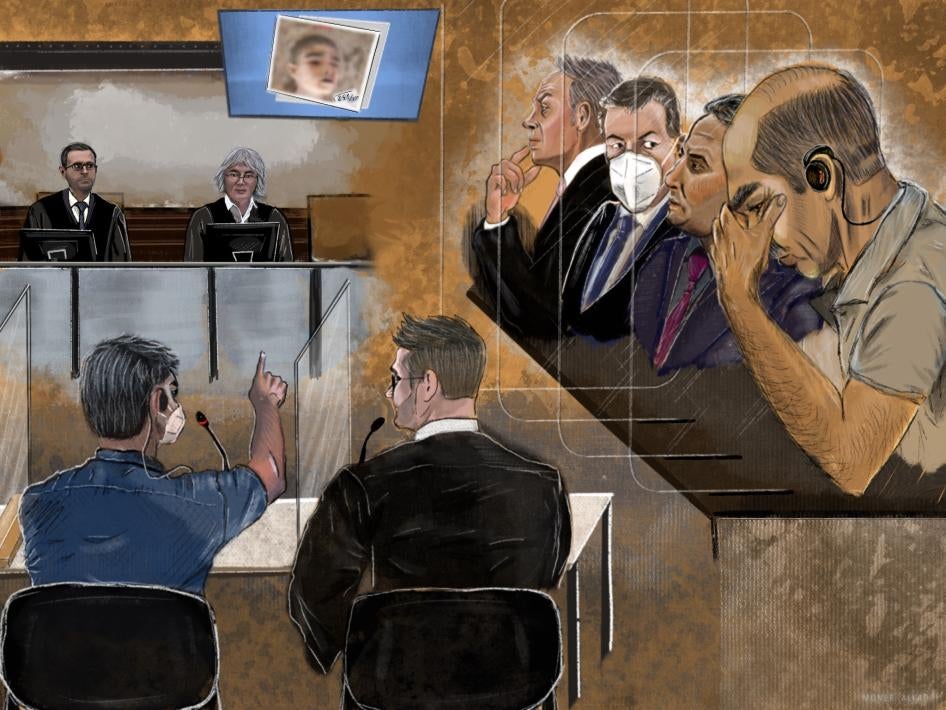

At least 17 survivors joined the trial against Anwar R. as what are known as “joint plaintiffs.” There were no joint plaintiffs in the trial against Eyad A..

Under German law, a victim of the crimes charged in the trial or a family member of a victim who was killed can join a criminal proceeding as a joint plaintiff, becoming a formal party to the proceeding. Joint plaintiffs play a critical role in proceedings. Joint plaintiffs and their lawyers can be present at the trial and have the right to: (i) request information on the status of the proceedings; (ii) make statements in court; (iii) access files; (iv) request that further evidence be taken; and (v) ask questions of witnesses and experts.

Joint plaintiffs must testify and also have the right to give statements during the proceeding. The joint plaintiffs in the Koblenz trial are represented by seven lawyers.

Survivors and families whose loved ones have been forcefully disappeared in Syria have organized numerous events around the trial, shining a light on sexual and gender-based violence in Syria and the forcefully disappeared. Since the Syrian conflict began in March 2011, sexual and gender-based violence in detention facilities has been pervasive.

At the beginning of the trial, Anwar R. was charged with two isolated cases of rape and aggravated sexual assault. The court updated the charges and legally qualified these acts as crimes against humanity in March 2021 after two victims’lawyers filed a motion to renew the indictment, as indictments should reflect the systematic nature of sexual and gender-based violence to do justice to the gravity of the crime.

In addition, several Syrian activists, artists, and asylum-seekers have been following the trial. Families for Freedom, an organization dedicated to remembering the forcefully disappeared, used the trial as an opportunity to spotlight the ongoing plight of the detained and disappeared. Members of the organization placed several photos of their missing family members in front of the court building at the beginning of the trial and held regular vigils there.

The testimony of witnesses who said they were detained in Branch 251 revealed that they had similar experiences after they were arrested by security forces in Syria. Across over 30 witness accounts, many reported that they were blindfolded at the outset and beaten with unknown objects on their way to what they claimed to be Branch 251.

According to the court in Koblenz, once arrested protesters arrived at Branch 251, they were subjected to a “welcome party” where they were beaten by guards with fists, sticks, cables, and metal pipes. The court said the guards also kicked them and smashed their heads against the wall until some lost consciousness. Some witnesses told the court that they were ordered to undress in front of several guards and remained naked. Others testified that during interrogations they remained blindfolded.

They were taken to overcrowded and run-down cells with injured and starving people. Many reported hearing screams as they were escorted between rooms and while in their cells. Several witnesses testified that they received no information as to why they were detained.

The witnesses testified to experiencing various types of torture in Branch 251. These included well-documented torture practices whereby Syrian authorities would force the victim to bend at the waist and stick their head, neck, legs, and sometimes arms into the inside of a car tire and beat them (“Dulab”) or beating the victim with sticks, batons, or whips on the soles of the feet (“Falaqa”).

These photographs, smuggled by a defector code-named Caesar out of Syria, were taken apparently as part of a bureaucratic effort by the Syrian security apparatus to maintain a photographic record of the thousands who have died in detention since 2011, as well as of members of security forces who died in attacks by armed opposition groups.

In the Koblenz trial, a forensic doctor analysed nearly 27,000 shots of 6,821 people. Based on the physical condition of the victims, the expert witness testified to the cause of death and whether the victims’ statements to police investigators about torture matched the forensic findings.

In October 2020 a French journalist, and author, Garance Le Caisne, testified at the trial about her encounters with Caesar. She is believed to be the only journalist to succeed in contacting the anonymous defector.

Over 80 witnesses have already testified in the case.

One of the major challenges of this trial is witness protection. Several witnesses from Germany and other European countries have canceled their hearing in court out of fear for their lives and safety, or that of their families. Several witnesses, some who were also victims, testified that they feared a risk to themselves and their families given their role in the trial. A witness stated that Syrian intelligence officers visited and threatened their family in Syria before they testified in Koblenz. At one point in the trial names of witnesses were leaked to the press. The leaking is under investigation.

German law allows for several measures to protect the identity of witnesses, including: (i) excluding the accused and the public during questioning; (ii) having the witness testify from a remote location via video; and (iii) letting the witness appear anonymously, which may include withholding the name and address of the witness and even altering their physical appearance.

In spite of the risks articulated by witnesses on the stand and the decision of many to withdraw, for the most part these measures were not used in the trial.

- Have German authorities taken steps to make the trial accessible to communities affected by the crimes charged and the general public?

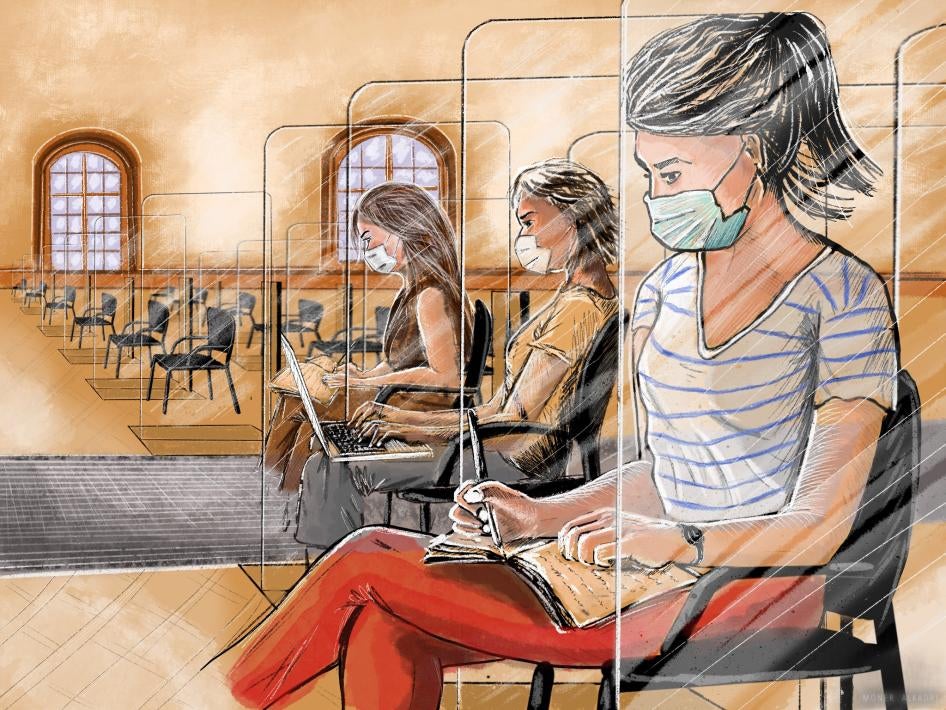

To be meaningful, justice should not only be done, but seen to be done. A key barrier to the trial’s accessibility has been the lack of translation. The trial is taking place in German. Individuals affected by the crimes charged are largely Arabic speaking. Although many of the interested Arabic speakers also have a basic knowledge of German, it is not easy to follow the procedure, especially due to the technical language used and the speed of the conversations in the courtroom.

From the beginning of the trial through August 2020, proceedings were only translated into Arabic for formal parties to the case, including the joint plaintiffs. Following a petition supported by the ECCHR and SJAC, claiming the lack of translation violated the rights of Arabic-language journalists to equally follow the development of the trial, the German Constitutional Court issued temporary order in August 2020 extending translation to pre-accredited Arabic-language journalists. However, there is no translation into Arabic for the public gallery, making it very difficult for affected communities to participate and follow the trial. As a result, the trial remains inaccessible to non-German speakers observing from the public gallery.

Although journalists are now entitled to use translation devices, the decision by the German Constitutional Court provided limited relief for Arabic-language media, because only a few Arabic-language journalists are accredited and therefore eligible. Information about the accreditation process was only available in German at the beginning of the process. The accreditation deadline has passed, and the court does not allow any subsequent accreditation.

Although the court allowed German to Arabic translation for the public gallery on the day the verdict in the case against Eyad A. was issued, the written judgment itself will only be available in German.

The trial is not being broadcast or streamed online. German courts do not provide transcripts of trials. German law allows audio recording of court proceedings in certain cases for scientific and historical purposes if the proceedings are of outstanding contemporary historical significance for Germany. However, the court initially rejected the suggestion to record the trial by academic institutions, citing witness protection concerns. According to the court, an audio recording of the testimony would also deter witnesses from testifying.

The blanket rejection of the request for audio recording does not do justice to the complexity and significance of the trial. Although, the safety of the witnesses is the first priority, the court could have taken a different view, allowing some testimony to be recorded if it wouldn’t put the witnesses in danger or deter them from testifying.

ECCHR, Human Rights Watch, and several nongovernmental groups and academics made second attempt in July 2021 to obtain an audio recording for the closing arguments. The court rejected the request.

Nongovernmental groups and journalists have taken it upon themselves to process the content of the trial and share it with the outside world. Organizations such as ECCHR or SJAC publish trial reports from each day of the trial.

The court in Koblenz occasionally publishes news releases on procedural or logistical matters concerning the trial, available on their website. This information is not being translated into English or Arabic. So far, neither judicial nor prosecuting authorities have conducted any outreach to the Syrian community in Germany or beyond.

Inadequate outreach to affected communities in Germany can have direct impact on the success of accountability effortsfor serious international crimes committed in Syria. Fear and mistrust on the part of Syrians in Germany inhibits their willingness to share potentially probative information with the authorities. Lack of awareness and understanding of the proceedings and systems in place further fuels these attitudes and most likely prevents Syrians from fully understanding these justice efforts and being able to contribute to them.

- Are there any other proceedings in Germany against Syrian officials or other parties to the Syrian conflict known to have committed abuses?

In June 2020 Alaa M., an alleged former member of the Syrian Military Intelligence Directorate, was arrested and is currently in pretrial detention. He allegedly worked as a doctor in a Syrian Military Intelligence prison and is accused of torture, killing, deprivation of liberty, and in one case attempting to deprive another human being of their reproductive capacity. Prosecutors said that Alaa M. left Syria and arrived in Germany in mid-2015, where he practiced as a doctor. The federal prosecution authority filed charges before the Higher Regional Court in Frankfurt. The trial is expected to begin this year.

In addition to these cases against Syrian state officials, there are numerous cases against members of armed organizations, such as the Islamic State (ISIS) or Jabhat al-Nusra, who are charged with war crimes and terrorism offences in Syria. Many of these proceedings do not take place on the basis of universal jurisdiction since the defendants are German nationals.

- Could Bashar al-Assad, Syria’s head of state, or other high-level officials be prosecuted under universal jurisdiction laws?

According to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), as a head of state, Bashar al-Assad is immune from prosecution before the national courts of a third country while in office. However, al-Assad could be prosecuted under universal jurisdiction laws once he is no longer in office. In January the German Federal Court of Justice ruled that there is no functional immunity for lower-ranking individuals who are accused of committing war crimes.

In addition to individual criminal accountability for serious crimes there is also the option to invoke state responsibility. The Netherlands announced on September 18, 2020, that it had notified Syria of its intention to hold that government accountable for torture under the United Nations Convention against Torture. Canada joined these efforts in March 2021. The Dutch initiative is an important step that could eventually lead to proceedings against Syria at the ICJ. This effort may prove to be yet another break in the concerted blockage on international accountability for crimes committed in Syria and help move toward urgently needed accountability.