(Nairobi) – Burundian authorities should drop baseless charges and release eight former Burundian refugees who were forcibly returned from Tanzania in August 2020. On February 26, 2021, the Muha High Court in Bujumbura ruled against their provisional release, even though the prosecution produced no evidence to justify their continued detention and their right to due process has repeatedly been violated.

“The Burundian state is adding insult to injury by prosecuting a group of forcibly returned refugees who have already been subjected to heinous crimes in Tanzania,” said Lewis Mudge, Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “This sham trial highlights both how politicized refugee returns are and the influence the executive still holds over Burundi’s courts.”

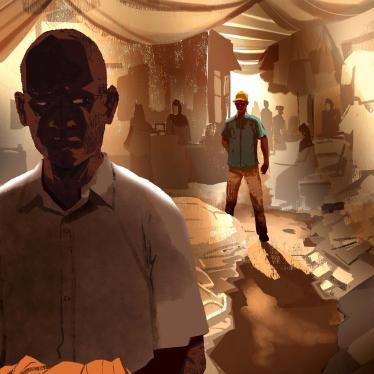

The eight men – Anaclet Nkunzimana, Felix Cimpaye, Radjabu Ndizeye, Revocatus Ndayishimiye, Saidi Rwasa, Emmanuel Nizigama, Didier Bizimana, and Ezéchiel Stéphane Niyoyandemye – were arrested in Mtendeli and Nduta refugee camps in Tanzania between late July and early August 2020. Tanzanian authorities detained them incommunicado for several weeks at Kibondo police station, where they were tortured.

The refugees said that during their time at Kibondo police station, Tanzanian national intelligence and police abused them and asked for one million Tanzanian shillings (US$430) to free them. Unable to pay, the refugees were taken by the security forces to the Burundian border with their hands tied and their faces covered. Four are currently in Bubanza prison and four in Muramvya prison.

Tanzania’s transfer of detained Burundian refugees or asylum seekers to Burundi without basic due process violates the international legal prohibition against refoulement, the forcible return of anyone to a place where they would face a real risk of persecution, torture or other ill-treatment, or a threat to their life.

A first pretrial hearing in their case was held on February 24, 2021, six months after their files were transferred to the high court on September 7. Burundi’s code of criminal procedure gives the court two weeks to organize the hearing after it receives the file. Prison authorities only informed the detainees late on February 23 that their cases would be heard the next morning.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Burundi ratified in 1990, states that “It shall not be the general rule that persons awaiting trial shall be detained in custody.” The Human Rights Committee, the international expert body that interprets the ICCPR, stated in a general comment that “Detention pending trial must be based on an individualized determination that it is reasonable and necessary taking into account all the circumstances, for such purposes as to prevent flight, interference with evidence or the recurrence of crime.”

During the hearing, one of the three judges said that the case was “political” in nature and the prosecution provided no evidence to support its charges of “participation in armed groups” and “threat to the national territorial integrity.” A source present said the prosecution failed to mention the first charge at all during the hearing. The prosecution accused the former refugees of discouraging fellow refugees in Tanzania from returning to Burundi to support the charge of threatening “national territorial integrity,” even though the refugees’ decisions to return to Burundi have no bearing on this issue.

The prosecution should drop these baseless charges, Human Rights Watch said. Instead, prosecutors should investigate the role of state agents, including the national intelligence service (Service national de renseignement, SNR), in the forced return of the refugees and the intelligence service’s alleged collaboration with Tanzanian police and intelligence agents.

In December, a TRIAL International report found that entrenched structural deficiencies in the Burundian judiciary have been exacerbated since the country’s political crisis began in 2015.

The government should institute wide-ranging reforms to fulfill President Évariste Ndayishimiye’s promise to end impunity after the May 2020 elections, and address the underlying politicization of the judiciary that has led to other similar abusive prosecutions, Human Rights Watch said.

Between October 2019 and November 2020, Human Rights Watch documented that Tanzanian police and intelligence agents, in some cases collaborating with Burundian authorities, arbitrarily arrested, forcibly disappeared, tortured, and extorted Burundian refugees and asylum seekers. Since November, Human Rights Watch has continued to receive credible reports of threats, harassment, and arrests of refugees in Tanzania.

On December 15, the special rapporteur on refugees, asylum seekers, internally displaced persons and migrants of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights expressed concern about the situation of Burundian refugees in Tanzania and reported violations of fundamental rights such as access to asylum and the principle of non-refoulement. The commission and the Office of the African Union Commissioner for Social Affairs should urgently press for the release of the unjustly detained former refugees.

On February 28, the United Nations Refugee Agency, UNHCR, expressed concern about messages of distress “from a group of 10 asylum-seekers currently in a detention facility in Mutukula, in northwestern Tanzania… express[ing] fears for their safety upon being deported from Tanzania.”

Burundian authorities have repeatedly spoken of the need for refugees to return from exile. In a speech during his swearing-in ceremony, Ndayishimiye said: “We call on all Burundians who wish to return to their nation to come back.” Yet in the same speech, he also threatened countries that support “Burundians who indulge in sabotage,” most likely referring to refugees who fled the country due to their political or human rights activism.

A Human Rights Watch report in December 2019 found that the fear of violence, arbitrary arrest, and deportation was driving many Burundian refugees and asylum seekers in Tanzania out of the country.

In Burundi, real or perceived opposition supporters, including returning refugees, are at risk of grave abuses, Human Rights Watch said. A UN Human Rights Council-mandated Commission of Inquiry reported in September 2020 that serious human rights violations have persisted in Burundi. The commission found that some returnees continued to face hostility from local officials and the ruling party’s youth wing, the Imbonerakure, and that “[r]eturnees have sometimes been victims of serious violations that have forced them to go back into exile.”

“The real crime in this case is the forced return of refugees from Tanzania to Burundi and the absence of due process or an effective remedy,” Mudge said. “If the prosecution cannot provide evidence to support their allegations, they should immediately drop their case and release the former refugees.”