(Washington, DC) – Future COVID-19 relief packages in the United States should be targeted to meet the basic needs of those most in distress, Human Rights Watch said today.

Three previous packages passed by Congress fell short of providing necessary aid and protections for families in poverty, failing to protect them against being saddled with debts, threatened with eviction, and having basic needs go unmet. President Donald Trump’s purge of inspectors general, who are providing oversight of the funds, heightens the risk.

“As financial hardships grow, many people in the United States will face dire choices, unless the US government takes concerted action to alleviate those concerns,” said Komala Ramachandra, senior business and human rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “During a public health crisis, the top priority for everyone should be staying safe and healthy, not worrying about how to pay the next bill.”

Social distancing measures have closed businesses, leaving millions of workers out of jobs or with reduced wages. School and care facility closures have forced people to prioritize caregiving at the expense of employment. A record 16 million people filed for unemployment benefits in the last three weeks, bringing the total recent job losses to 10 percent of the US workforce. These numbers are expected to grow, with nearly 4 in 10 Americans reporting either job or income loss. Many of the jobs lost have been low-wage, hitting those already living paycheck-to-paycheck.

The economic crisis has severely affected many families’ ability to afford food, medicine, rent, and utilities. Food banks across the country have reported serving record numbers of meals. Nearly a third of apartment renters in the United States did not pay their April rent.

Suspend Evictions, Utility Cutoffs, Debt Collection

Existing congressional relief packages provide protections against new eviction proceedings for certain types of housing and foreclosures for federally backed mortgages. But they don’t provide protection for those who cannot afford utility bills, including water and electricity, or pay debts, like medical or credit card bills.

Various state and local governments have adopted more expansive protections. At least 24 states have moratoriums on utility terminations for non-payment. Some states, such as California, have ensured that water is turned back on in households previously disconnected from water services. Some have frozen eviction and foreclosure and provided grace periods after the crisis to allow time to gain income.

State responses to debt collection vary greatly. Massachusetts instituted limits on certain debt collection activities, while West Virginia declared professional debt collectors an “essential business” exempt from the stay-at-home order. For people with limited resources, unpaid bills may pile up, leading to garnishment of wages and bank accounts and negative credit reports, with a long-term impact on access to housing, loans, insurance, and jobs.

This patchwork approach leaves many gaps in protection. Federal fixes have been proposed in Rep. Nita Lowey’s Take Responsibility for Workers and Families bill. House Financial Services Committee Chairwoman Maxine Waters has introduced a comprehensive consumer protection package; a complementary bill is in the Senate.

To uphold the right to adequate housing, governments should take measures to protect people from unfair evictions or unduly losing their homes. In times of severe economic and financial crisis, governments need to put in place special protections for vulnerable people and ensure that relief measures for people with very low or no income are sufficient to protect the right to adequate housing. These can include direct financial assistance for or deferral of rental and mortgage payments; moratoriums on evictions due to arrears; rental stabilization or reduction measures; and suspending utility costs and debt collection.

Congress should draw on existing proposals to protect everyone facing job loss or economic hardship from evictions, utility cut-offs, and debt collectors.

Target Payments to Low-Wage and Unemployed Workers

Previous relief packages provided only a single direct payment to individuals under a certain income level and temporarily increased unemployment insurance, including for domestic workers and the “gig” economy. These protections fell far short of ensuring that people can meet their basic needs and left significant parts of the workforce ineligible.

Benefits only go to people with a Social Security number, excluding millions of working immigrants who pay US taxes. People over 16 whose parents can claim them as dependents also won’t receive financial support. These are some of the most vulnerable workers, hit the hardest by job losses and pay cuts and who went into the crisis with the fewest resources.

Although the Families First Coronavirus Response Act guarantees paid leave for about half of US workers and extended paid leave for some parents whose children are now out of school, it does not apply to employers with 500 or more employees. Many of these companies employ workers deemed essential. Policymakers should extend paid sick leave to all workers, at-risk workers, and workers with family members who are sick or at risk. Due partially to gender bias and the enduring gender pay gap, women are at most risk of leaving the economy without guaranteed extended paid leave while workers manage childcare.

Ensure Affordable Medical Treatment

None of the relief packages ensure affordable and accessible COVID-19 treatment. Earlier packages included measures for free testing, though some people tested have received bills.

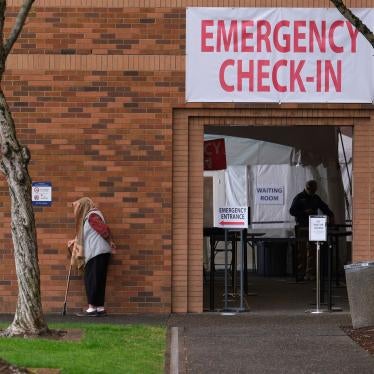

At least 28 million Americans were uninsured before the crisis and that number is likely to increase dramatically as people lose their jobs and employer-based insurance. While hospitals cannot turn people who need treatment away, many uninsured people may delay or not seek treatment out of fear of financially crippling medical bills. An uninsured woman in Pennsylvania died after refusing to go to the hospital, fearing she could not afford to pay. The cost of care can be exceedingly high: hospitalization and treatment can range from $14,000 to over $70,000.

The Trump administration has refused to allow a national open enrollment period for health insurance under the Affordable Care Act, though it is available to those who have recently lost their jobs and several states have opened emergency enrollment periods. Affordability of these plans remains an obstacle, particularly in the 14 states that have not accepted Medicaid expansion.

The administration has said it will use part of the $100 billion earmarked for hospitals in an earlier relief package to pay for COVID-19 treatment for the uninsured, which experts estimate could consume up to $40 billion. Healthcare providers were expecting these funds to cover other costs, including temporary structures and medical supplies, so it remains unclear whether this allocation will be sufficient for an already strained healthcare system.

The right to the highest attainable standard of health includes affordable care and access to health facilities for all to prevent, treat, and control epidemic diseases. Congress needs to ensure that everyone in the US can get affordable health care, while also ensuring that hospitals and healthcare providers have the resources needed to provide care. Congress should also allocate funds to collect data on specific groups affected by COVID-19, such as African Americans and Latinos, to ensure appropriate distribution of prevention and treatment.

Establish Effective Oversight

Existing and future relief packages will provide businesses with financial support to weather the economic impacts of the crisis. Future recovery packages may also include significant investments in infrastructure. Funding for businesses thus far has not included adequate oversight to ensure that funds are appropriately targeted at protecting workers.

Funds could be subject to political favoritism and self-dealing, compounded by the unprecedented amounts being appropriated, the speed at which the government wants to distribute them, and the administration’s efforts to undermine oversight, even before operations begin.

A special investigator general oversees a $500 billion fund for corporations, but Trump added a statement when signing the law claiming the authority to prevent it from reporting to Congress. The administration nominated Brian Miller, a White House lawyer, for the role, raising concerns that Miller will not provide independent and impartial oversight.

The package also established the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee, a council of inspectors general to oversee the administration of relief funds. The committee elected as its chair Glenn Fine, the Defense Department’s acting inspector general, who had served in Republican and Democratic administrations, but Trump abruptly removed him from the post.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced a bipartisan congressional oversight panel to oversee how relief money will be allocated and spent, which she said was aimed to “protect against price gouging, profiteering, and political favoritism.” The panel will have subpoena power and expert staff to guide decision-making in line with public health priorities.

“Independent oversight is critical to making sure that the trillions of dollars in public money to help people and businesses in distress actually gets into the hands of those who need it,” Ramachandra said. “The Trump administration’s efforts to weaken oversight should be an alarm bell that Congress should not approve of any additional funding without transparent, independent, and bipartisan oversight.”