Summary

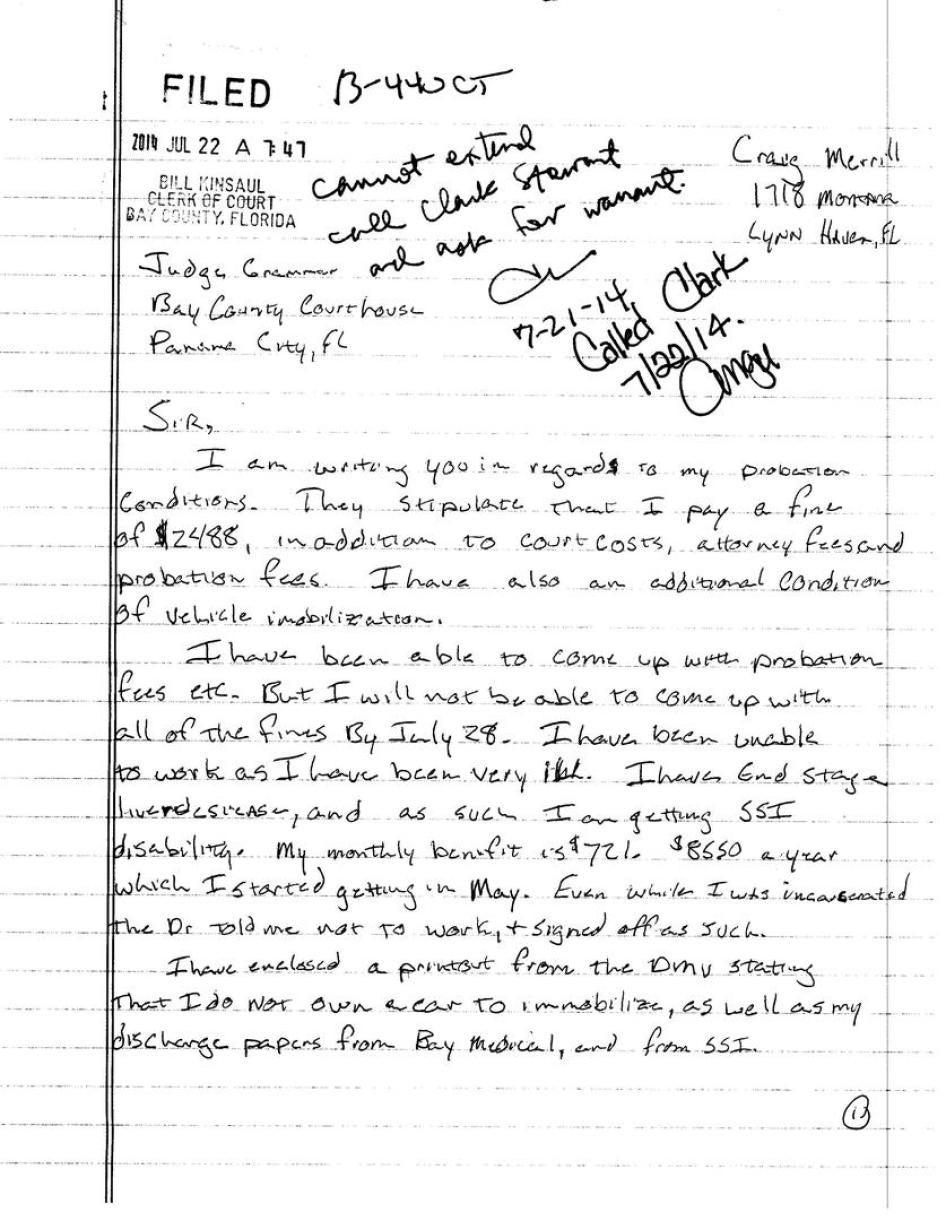

Cindy Rodriguez, a 53-year old woman living in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, had never been in trouble – “never had a parking ticket” – until 2014, when she was charged with shoplifting. Rodriguez survives on disability payments due to injuries to her neck and back, and lives in constant pain. When her case went to court, she was represented by a public defender, provided to individuals living in poverty who meet certain criteria. Rodriguez said her public defender advised her to plead guilty and accept probation, saying it was the best deal she would receive from the state.

Rodriguez was placed on probation for 11 months and 29 days under the supervision of Providence Community Corrections, Inc. (PCC), a private company that had contracted with the Rutherford County government to supervise misdemeanor probationers. Rodriguez’s lawyer told her probation was nothing to worry about, that she would just have to visit her probation officer once a week and pay her fees and fines. When she informed the judge about her stark financial situation and disability payments, he told her to do the best that she could. She owed the court US$578 for the fine and associated fees, and on top of that she would have to pay PCC a $35-45 monthly supervision fee. PCC also conducted random drug tests, though she was not charged with a drug-related offense, for which she would pay approximately $20 a test. The costs of probation ruined her life.

Every time Rodriguez went to PCC to visit her probation officer, she was pressured to make payments. On one visit when she did not have the money to make a payment, her probation officer told her that she would “violate” her and that she would go to jail, which is what happened. Rodriguez turned herself in, saying it was “the most humiliating thing I’ve ever had to do in my whole life…. They took a mug shot of me, fingerprinted me, and treated me like I was garbage for about two and a half hours. Then [they] told me I could go home, they'd see me next time. That's what the police officer said, ‘I'll see you next time. You'll violate again.’ That's how they treat you.”

Feeling the financial pressure of probation, backed by the threat of jail time, Rodriguez was spending far too much of her $753 monthly disability check on probation instead of basic necessities. She told Human Rights Watch: “I struggled to pay them the payments they needed every week. I ended up selling my van, because I was threatened all the time. If I didn't make the payments, they were going to put me in jail. I lost my apartment, and it's been a struggle ever since…. There were times [my daughter and I] didn’t eat, because I had to make payments to probation.” The consequences of her time on probation are still haunting Rodriguez: “No matter what I do, I can’t get back up.”

Rodriguez’s experience with private probation is not unique. Probation is a criminal sentence in lieu of jail time and is widely employed as an alternative to incarceration in the United States. One goal of probation supervision is to ensure that an individual does not commit further offenses, while also providing rehabilitative services. Traditionally performed by state agencies or local law enforcement, probation supervision for misdemeanors and criminal traffic cases has in many states increasingly been outsourced to for-profit, private companies.

This report focuses on the impact of private probation on people living in poverty in four states: Florida, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee. In these four states, private probation is predominantly imposed for misdemeanor offenses, such as disorderly conduct, possession of small quantities of illegal drugs, or petty theft, and criminal traffic offenses, including driving with a suspended or revoked driver’s license, not maintaining vehicle insurance, and driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol. From November 2016 to October 2017, Human Rights Watch interviewed individuals supervised by private probation companies, as well as judges, law enforcement officials, lawyers, and other experts.

This is Human Rights Watch’s second report on the impacts of private probation and the offender-funded criminal justice system. It follows up on the first report, Profiting from Probation: America’s “Offender-Funded” Probation Industry, released on February 4, 2014, focusing on the private probation industry in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. One of the main findings of that report was evidence of “pay only” probation, or the imposition of a probation sentence simply to supervise the payment of costs, rather than as an alternative to a jail sentence. Pay only probation means that an individual who can pay their court costs up front is not subject to probation supervision and its associated conditions and costs, leading to significantly different financial and legal outcomes for poor defendants. The 2014 report also documented cases of incarceration when an individual was unable to pay their supervision fees. The current report documents the impacts of private probation in a different geographic region, focusing on Florida, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee. The report finds that the impacts of private probation are unique in every state, and research did not find widespread use of pay-only probation or incarceration in cases when a person was unable to pay supervision fees.

This report finds that private probation companies exert significant control over the lives of people on probation. In the states studied for this report, private probation companies can impose supervision fees, order drug and alcohol tests, and, if a person does not fulfill all the terms and conditions of their probation, they can issue a violation of probation and request arrest, which can lead to jail time. The services of private probation companies are attractive for cash-strapped jurisdictions because they typically do not charge for their services; instead, their revenues and profits come entirely from probationers’ fees. The companies, therefore, have a direct financial interest in keeping their clients under probation as long as possible, and using every tool available to urge payment of fees, particularly those paid directly to the company. Judges also often require people on probation to complete courses that ostensibly improve public safety and support the rehabilitation of the person on probation, including alcohol and drug testing, domestic violence and anger management courses, and monitoring devices, such as electronic instruments that monitor a probationer’s location or alcohol consumption. Many private probation companies offer courses, treatment, and monitoring device services to courts, directly benefitting when courts mandate these services as conditions of probation. The cost for all these services is passed directly to the probationer in all four states researched for this report, creating an “offender-funded” system.

The spiraling costs many probationers face only partly explains how misdemeanor or criminal traffic offenses can lead to severe criminal debt in the US. The same individuals who qualify for a court-appointed public defender or government benefits, such as food stamps and housing support, may still be ordered by courts to pay hundreds or thousands of dollars not only in fines levied as punishment for an offense, but in various fees and other surcharges. Courts bill defendants for prosecutors, public defenders, jailing and transportation, and other costs associated with the court, as well as unrelated fees, like the sheriff’s retirement fund or brain injury trust funds. In all four states researched for this report, if probationers cannot pay for the direct or indirect costs of probation, they face a number of legal consequences, including jail time. The incarceration of people who do not pay fines and fees because they are genuinely unable to pay was outlawed in 1983 by the US Supreme Court, yet it remains a reality.

Not all types of criminal defendants are subject to private supervised probation. Felony probation, in contrast to misdemeanor and traffic probation, continues to be monitored by state agencies, and is subject to greater transparency and accountability standards. In some misdemeanor cases, judges will allow probationers who have met their financial obligations to the court to transition to unsupervised probation. However, defendants without adequate resources to pay court fees, or who need more time to make payments, often must continue under supervision, subjecting them to additional fees, testing, and monitoring.

Increased supervision, monitoring, and testing create more opportunities for a violation of probation, which is why many individuals on private probation feel that they are “set up to fail.” When a person does not meet the weekly and monthly obligations of probation, then a private probation officer can issue violation of probation, which can entail the issuing of a court summons or an arrest warrant. Many probationers interviewed for this report said their probation officers made threatening or coercing statements when they did not have enough money to pay for their supervision and other conditions. In all four states researched for this report, after being arrested or summoned to court, a probationer will have to go before a judge once again, potentially through several hearing dates, and may be subject to additional court costs and fines, extended probation periods, new probation conditions, jail time, and new opportunities to fail. This can lengthen a person’s criminal record, which has long-term effects on the ability to get a job or find housing.

In Florida, Tennessee, and Missouri, probationers often must pay court costs, fines, and supervision fees directly to the private probation officer. While costs owed to the courts are not unique to private probation, the probationers supervised by companies in all four states included this report told Human Rights Watch that the payment of these costs was burdensome, and many did not distinguish between costs owed to the court system and the private probation company. In cases in Tennessee and Florida, where only partial payments are made or when a probationer is in arrears, courts leave probation officers free to decide how payments are allocated between company fees and courts costs. If most payments are going to the probation company rather than the court, then a person can be left with significant unpaid debt to the court at the end of their probation.

When non-payment of fines and costs is the only reason that an individual has violated probation, the US Supreme Court has said that US courts are required to ensure that they do not jail a person who failed to pay because they were genuinely unable to do so. Human Rights Watch finds few instances in the four states researched where individuals were incarcerated because they were unable to pay court costs and probation supervision fees. However, research in the four states reveals that people more often face incarceration for inability to pay for additional probation requirements, including court-mandated classes or background checks. If an individual is using his or her limited income to pay probation supervision fees and court costs, they may have difficulty saving enough to also cover a required course, regular drug testing, or background checks. Some probationers, fearing the consequences of reporting to probation without enough money in hand, stop reporting entirely. As a result, probationers were not facing incarceration for failing to pay their fines and fees, but rather for “proxies” for failure to pay, including not completing classes, submitting to drug tests and treatment, conducting background checks, or other conditions that impose financial a burden because they could not afford to pay for these requirements.

In some of the states researched by Human Rights Watch, unpaid fines and court costs can result in a suspended or revoked driver’s license, which can be the result of private probation officers applying payments to probation rather than court costs. A revoked driver’s license can have a catastrophic impact, as many people on probation feel that they have no choice but to drive, particularly in the rural regions of the states studied for this report, though this can have criminal consequences, including going back on private probation. This endless cycle of criminal charges, probation, and debt can trap some until they have no option left but jail. Those who can pay down their debts usually escape the cycle.

The impact of onerous conditions of probation, including payment of private probation fees – from ballooning debt to possible incarceration – often extends to family, friends, and the wider community. Many probationers rely on the help of friends and family members to make payments, drive them to probation appointments and court hearings, and assist with housing and food. Some family members also provide emotional support through stressful and uncertain times.

Children are particularly impacted when a parent is arrested, incarcerated, or simply does not have the money to pay for basic needs or child support because they are paying probation fees. Family members step in to care for children while a parent is attempting to resolve criminal cases and comply with probation conditions. The offender-funded system of justice is most burdensome and punitive for those who cannot afford its costs.

As states attempt to reform criminal justice systems and reduce spending on incarceration, many have increased their reliance on alternatives to incarceration. Private companies have entered the market to offer states, counties, and municipalities lower cost options for criminal justice functions. New systems are emerging in the changing landscape of criminal justice, but they often lack transparency, regulation, and oversight, particularly for the individuals most vulnerable to abuses.

The focus on criminal justice debt and its impacts on people living in poverty has gained increased public attention in recent years, though much action is still needed to correct these abusive practices. Some states, like Kentucky and Tennessee, have increasingly regulated excesses in the private probation industry, yet implementation and oversight are sorely lacking. States need to do more to ensure that courts and private probation companies are not acting abusively because of their incentive to maximize profits, and that they instead provide quality services with the intent of supporting individuals to successfully complete probation.

Probation companies should review and assess their practices to ensure that they are complying with state and national legal standards and in a manner that fully respects the rights of the people under their supervision. Working with state governments, probation companies should establish processes for identifying and addressing any attempts by probation companies or courts to sidestep rules or abuse their power. Greater transparency, paralleling government agencies that provide probation supervision services, can improve accountability in their operations.

The drive to privatize criminal justice services in many states is fueled by budgetary shortfalls. Private probation companies shift the cost of supervision from the state to the system’s “users,” and that larger dynamic gives rise to many of the abuses outlined in this report. In the face of shrinking budgets and increasing costs, probation that is “free” for the courts offers an attractive option for states and local governments. State and federal governments should examine alternative ways to reduce criminal justice system costs in a way that preserves and promotes both justice and safety.

Recommendations

To the Federal Government

- Expand the authority of the Department of Justice to investigate court practices, and authorize an examination of the impact of criminal justice debt, including fees for private probation supervision and associated conditions, on the poor. An investigation should, at a minimum, include analysis of the processes to determine an individual’s total criminal justice debt, their ability to pay within a reasonable timeframe, long-term impact on the individual and his or her family, collection methods by public officials and private agencies, and consequences for inability to pay.

- Establish national standards for criminal justice debt, including guidelines on ability to pay determinations and collection practices.

- Through the Bureau of Justice Assistance, make technical assistance and resources available to state and local court systems to end offender-funded criminal justice systems.

To State Governments in Florida, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee

- Cease reliance on user fees to fund criminal justice and other state systems.

- Ensure the process of selection of and contracting with private probation agencies is free of conflicts of interest.

- Implement open bid contracting for private probation companies, with adequate transparency of all documents, including description of services, fees, and restrictions. Allow relevant state agencies, whether an administrative body or the state Supreme Court, to make decisions on the use of private probation in a given jurisdiction, removing discretion from judges or other local authorities.

- Eliminate exclusive contracts for private probation companies.

- Require contractual terms that eliminate incentives for private probation companies to increase their revenue by removing any discretion on the part of private probation officers regarding supervision fees and surcharges, collection methods, sanctions for violations, and probationary periods.

- Require private probation officers to disclose any conflicts of interest for themselves or their company to the judge prior to making recommendations on sanctions, fines, or other consequences for violations of probation.

- Empower an independent state agency to oversee compliance with all private probation rules and regulations, including through regular monitoring, robust reporting requirements, and sanctioning power.

- Ensure transparency in the operation of private probation companies.

- Establish procedures for relevant state agencies to vet and track information about private probation companies and where they operate.

- Track the number of probationers under the supervision of each private probation company, including the length and outcome of supervision; any violation of probations, the reasons for each violation, and their ultimate dispositions; description of other services provided to probationers under supervision, such as community service or work placements, classes, drug testing, monitoring devices, and their outcomes; and a breakdown of all fees collected.

- Disclose potential or perceived conflicts of interest, particularly regarding recommendations on sanctions, fines, or other consequences associated with a violation of probation.

- Publish all of the above information on a regular basis, both online and in print.

- Establish safeguards to ensure legal financial obligations do not create undue hardship for those who cannot afford to pay.

- Formulate guidelines that ensure criminal justice costs, fees, and fines are adjusted to a person’s ability to pay so that they have comparable impact for people with differing levels of income/wealth, such as a “day fines” system. Establish clear processes for seeking waivers, reductions, and substitutes for all required cash payments, especially court costs, fees, and fees paid to private service providers.

- Exempt indigent defendants from all courts costs and probation fees. Ensure judges have, and are aware that they have, the discretion to waive fees and costs.

- When conditions of probation, such as courses, treatment, or monitoring devices, are considered vital for public safety, provide these services on a sliding fee scale or without cost. Always provide these without cost for indigent defendants.

- Ensure that the collection of court costs is not used as a central measure of judicial or clerk performance.

- Eliminate payment of court costs and fees as conditions for successful completion of probation, including payment of costs associated with courses, monitoring devices, treatment, and other probation requirements.

- Create adequate regulation to safeguard probationers unable to make payments toward court costs, probation fees or associated conditions from being incarcerated, having their driver’s license revoked, or other punitive measures unrelated to their offense.

- Implement alternative methods to address failure to pay violations, such as a system of graduated sanctions.

- Provide clear education, training, and professional conduct standards for private probation officers and any other personnel working with probationers.

- Restrict ability of private probation companies to collect only supervision fees, and not handle restitution, fines, and court costs payments.

- Standardize drug testing guidelines, procedures, and cutoffs across criminal justice institutions.

- Require private probation companies and officers to provide probationers with clear information about their rights.

- Establish state-level agencies, or expand the mandate of existing institutions, that are empowered to monitor private probation companies, enforce regulations, and investigate grievances from people on probation.

- Create monitoring protocol to ensure compliance with all state and federal regulations pertaining to probation supervision.

- Authorize grievance mechanisms to handle issues arising from all aspects of supervision, including assignment to private probation, payments and waivers, drug testing, and probation officer misconduct or abuse. Require the timely and transparent handling of grievances. Provide written guidance on grievance procedures to every individual at the time they are placed on private probation. Create systems for appealing decisions of the grievance mechanism to courts.

- Clearly post information on rules and regulations, including the process to submit a complaint, at every probation reporting office and courtroom.

- Create guidelines to protect probationers who raise concerns or complaints about their supervision from retaliatory action by probation officers, judges, clerks, or other court officials. Protect confidentiality of complainants.

- Empower state oversight agencies to censure or suspend private probation companies or specific officers for non-compliance.

To Courts and Judges in Florida, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee

- Ensure selection of private probation companies is done in a public and transparent manner, with no actual or perceived conflicts of interest. Judges should refrain from engaging in or making any statements about the selection or contracting with private probation companies.

- Ensure that only appropriate officers of the court engage in decision-making for probation orders and violations of probation. Restrict access of private probation officers from the section of the courtroom reserved for attorneys, court personnel, and litigants (commonly known as “the bar”), as is already the practice in some states.

- Guarantee that the right to counsel is made known during all sentencing and violation of probation hearings, and that an individual can request a public defender in any of these proceedings.

- Evaluate an individual’s ability to make payments toward fines, fees, and the costs associated with probation and its conditions at the time of sentencing. Waive costs when a defendant cannot afford payments, or make alternatives available, such as community service.

- Ensure that individuals offered probation as part of plea deals are aware of all details related to private probation, including supervision requirements, conditions, costs, and consequences for noncompliance before accepting. In addition, ensure that individuals sentenced to probation are aware that they cannot be incarcerated if they are unable to pay for supervision, drug tests, or other conditions of probation, and are entitled to a hearing before the court to determine if they have the ability to pay. Communicate and distribute information on private probation complaints and appeals processes at the time that a probation order is made.

- Use appropriate systems for notice and summons when individuals violate their probation for inability to pay. For example, where appropriate, instead of issuing arrest warrants, use a less burdensome summons procedures.

- Ensure compliance with Bearden v. Georgia through hearings that meaningfully assess an individual’s ability to make payments to the court and/or private probation company. Similarly, if an individual has violated probation because of an inability to pay for a drug test, class, training, treatment, monitoring device, or other condition of probation, judges should conduct an ability to pay determination and not incarcerate them if unable to pay.

To Prosecutors

- Include unsupervised probation or alternatives that do not incur fees in plea deals with indigent defendants or where supervision is not reasonably required.

- When offering a plea agreement that includes private probation supervision, ensure that the defendant is aware of all details related to supervision requirements, conditions, associated costs, and consequences for noncompliance before accepting the offer.

- Restrict conditions on probation included in plea deals to those that are truly necessary, offering low cost or free alternatives whenever possible.

To Private Probation Companies

- Establish clear guidelines for probation officers on interactions with clients and create systems of internal accountability for ensuring compliance with the guidelines. Ensure that staff never threaten or coerce probationers who are unable to pay, and never refuse supervision, drug testing, background checks, courses or other conditions, due to insufficient funds.

- Exercise adequate diligence, including background checks and screenings, in hiring probation officers and any other staff who have contact with individuals being supervised under court order, whether that be through a treatment program, course, or monitoring system. Create and educate staff on their professional and ethical responsibilities, including procedures for investigating and sanctioning violations.

- Require regular training for staff on best practices in probation supervision. Provide probation officers information, tools, and resources so they are able to offer rehabilitative services and address challenges in the life of probationers related to employment, transportation, housing, healthcare, mental illness, substance abuse treatment, and childcare.

- Educate probationers on their rights.

- Provide clear verbal and written information about application of payments toward restitution, court costs, and probation fees.

- Establish a process by which probationers can apply for waivers, work programs, or other alternatives to cash payments, through the probation company and the court. Make all steps of that procedure and the number of pro bono/sliding scale clients publicly available.

- Establish a method for receiving and addressing complaints from probationers. Disseminate information about company and state complaint processes to probationers when commencing supervision and make complaint information visible in all probation offices. Due to fears of reprisal, allow confidential complaints to be made.

Methodology

This report examines the use and impact of privatized probation services for misdemeanor offenses in four US states: Tennessee, Missouri, Kentucky, and Florida. These states were selected because of the historic and widespread presence of privatized probation services, varying levels of regulation and oversight, and reports of human rights abuses associated with private probation companies. Human Rights Watch published a report on private probation companies in 2014 focusing on abuses in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi.

In late 2016 and 2017, Human Rights Watch conducted more than 150 interviews with probationers and their families; criminal defense attorneys and public defenders, judges and court staff, prosecutors; criminal justice experts; members of civil society organizations; attorneys who have investigated or brought lawsuits against private probation companies; local law enforcement; and probation company representatives. Due to concerns about reprisals, Human Rights Watch has withheld the identity of certain probationers and their family members, unless they consented to being identified; the report indicates where pseudonyms were used. Other individuals, primarily attorneys and court staff, requested anonymity for fear of impact on their ability to do their jobs; their names and other identifying information have not been included in this report.

Human Rights Watch visited over 20 county and municipal courts, and in nearly all of them observed cases where misdemeanor offenders were either sentenced to private probation or were in hearings for violation of probation terms. In addition, we interviewed dozens of probationers at reporting locations in Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee. We reviewed court records, where available, to verify details relating to individual cases.

Human Rights Watch, in collaboration with civil society organizations and pro bono lawyers, obtained information through records requests in Kentucky and Tennessee. Records requests were sent to every county in Kentucky, in partnership with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Kentucky, to ascertain their use of private probation companies.[1] In Tennessee, Human Rights Watch obtained records on private probation permits, revenue generated for the Private Probation Services Council, and quarterly reports filed by private probation companies in Giles County. In Florida and Missouri, Human Rights Watch relied on case documents and practices available through online databases.

Detailed questionnaires were sent to 22 companies operating in the four states researched for this report, particularly those companies that were researched for this report. Two company representatives provided written responses: Private Probation Service TBN, LLC, of Hillsboro, Missouri, and the now defunct Correctional Services Incorporated (doing business as Tennessee Correctional Services) in Memphis, Tennessee.[2] PSI Probation of Cookeville, Tennessee, provided an interview by phone, responding to several questions about how they supervise probationers.

Human Rights Watch also conducted extensive desk research through academic articles, media reports, and civil society reports pertaining to legal financial obligations, private probation, and alternative models for criminal justice debt.

No compensation was offered for interviews. Everyone interviewed for this report was informed of the nature of the research and that their participation was completely voluntary.

|

What’s the difference between a fee and a fine?

Fines are generally imposed as a penalty for a crime, either on their own or in conjunction with a jail or prison sentence. Courts also charge a wide range of fees that may not be directly related to the punishment of a crime, but rather the process of prosecution and the functioning of the court. There may also be fees and surcharges completely unrelated to court function, like state funds to support specific causes, retirement funds, and surcharges like partial or late payment fees. This report refers to court-imposed fees and fines as court costs. Restitution can also be imposed by a court and is meant to compensate a victim of a crime for their losses. Costs associated with restitution can place significant financial burdens on an individual. However, this report does not address restitution obligations. Private probation companies can charge their own fees for supervision and the cost of other probation conditions, like courses, treatment, monitoring devices, and drug testing. These fees are not included in the term court costs. Regular payment of fines, court fees, restitution, and private probation fees are all generally conditions for the successful completion of probation. |

I. Background: Offender-Funded Criminal Justice Systems

Budgetary Pressures in the Criminal Justice System

States, counties, and municipalities across the United States face budget shortfalls, which have increased since the economic recession of the late 2000s and early 2010s.[3] Budgetary pressures have forced state and local governments not only to cut expenses but also protect and augment revenue sources. Numerous state and local governments now pay some or all of the costs of running their criminal justice systems through a combination of taxes and various fines and fees.[4] In some cases, the fines and fees generated through the criminal justice system are also used to cover state or local expenditures not related to the judicial system.[5]

States and localities are generating more revenue to fill budget shortfalls by shifting the costs of criminal justice functions to the individual “users.”[6] Some jurisdictions have turned to mandatory fines and fees, where a judge has no discretion, particularly for minor offenses and traffic violations.[7] A number of jurisdictions have come under fire for using local courts to generate revenue by fining individuals for minor infractions. And in Missouri, residents of Pagedale filed a class action lawsuit in 2015 against their municipality for excessive fines under local ordinances, which include restrictions on hedge height, curtain appearance, and the way that pants must be worn.[8]

Governments also impose a multitude of fees and surcharges on defendants to raise revenue. Fees are regularly imposed for various law enforcement functions, including arrest, processing and intake, drug testing (even in cases that do not involve drugs or alcohol), clerk services, and jail boarding. Florida prescribes a mandatory minimum fee of US$50 to apply for indigent status to qualify for a public defender, a minimum $50 fee for the assistance of a public defender in a traffic or misdemeanor case, and an additional $50 “cost of prosecution fee.”[9] While judges have the power to raise some of these fees, they do not have the discretion to waive or reduce them below the mandatory floor.[10]

Defendants in some states are also required to contribute to the costs for public defenders, state’s attorneys and prosecutors, juries, jail boarding, and prosecution. Judges can also add on unrelated surcharges for a wide range of causes, including sheriffs’ retirement funds, law enforcement training, crime victims’ restitution funds, brain and spinal cord injury programs, teen courts, children’s advocacy centers, and rape crisis centers, to name a few.[11] In Cape Girardeau County, Missouri, for example, local judges regularly imposed fees of $150-$300 on misdemeanor defendants for the “Cape County Law Enforcement Restitution Fund” (normally restitution funds are for victims of violent property offenses, which are often felonies).[12] Multiple counties in Missouri charge inmates a daily jail boarding fee, ranging from $22.50-$45.[13] These are just some of the examples of fees charged in the four states researched.

Individuals in the criminal justice system must also increasingly bear the costs of probation supervision and other alternatives to incarceration, whether provided by public or private entities. In all four states studied for this report, probationers make regular payments for supervision, in addition to paying their fees, fines, and any restitution costs. Several states place a cap on how much probation agencies, both public and private, can charge, while some states, like Florida, set a minimum monthly payment.[14] In all the states in this report, the payment of costs, including fees to private companies, are a condition of probation. Failure to comply with all conditions of probation can lead to a violation of probation, arrest warrant or criminal summons, hearing, revocation, and potentially incarceration. Efforts to provide alternatives to incarceration through private probation are often also seen as ways to increase revenues for cash-poor courts, placing undue burden on poor defendants and trapping them in endless cycles of criminalization and debt.[15]

The Motivation to Privatize Probation

Many state probation and parole authorities are moving away from supervising misdemeanor probationers, in part due to budget constraints associated with handling the growing probation and parole populations.[16] Under these circumstances, local courts must find alternative means to supervise probationers.[17] Private companies offer cash-strapped courts an appealing alternative by offering supervision services free of cost to the courts, and rely on fees paid by people on probation as their source of revenue.[18]

Florida was the first state to allow private entities to supervise probationers, with the approval of Salvation Army Misdemeanor Probation in 1975, followed by legislation permitting approved private entities to supervise probation in 1976.[19] Missouri and Tennessee followed in 1989.[20] While Tennessee requires private probation companies to apply to a state council for approval before providing services,[21] Kentucky, Florida, and Missouri leave the selection and approval of private probation companies to local courts and judges.[22] There are also few rules or regulations and little to no oversight regarding the qualifications required of company probation officers.[23] Most states that allow the use of private probation companies restrict their use to certain types of crimes, usually misdemeanors and traffic offenses, though Tennessee permits private supervision for felony cases under particular conditions.[24]

The private probation companies studied in this report do not charge the court system for their services, and instead generate revenues from probationers directly, through supervision fees and provision of other services, including drug testing, treatment, classes, and electronic monitoring. These services may be court-mandated conditions of probation. While fee structures may be written into contracts between private probation companies and courts, Missouri statute specifically states that neither the state nor any county “shall be required to pay any part of the cost of probation and rehabilitation services provided to misdemeanor offenders” by private agencies.[25]

In some states, including Tennessee, Florida, and Missouri, private probation companies are permitted to collect costs owed to the court by defendants, such as fees, fines, and restitution. Often, smaller jurisdictions that struggle to maintain personnel to enforce and collect these costs rely on private probation companies. A former director of a Tennessee private probation company claimed the company’s role was to “enforce court requirements and collect fees,” allowing the county to dramatically increase its collections.[26] Kentucky, however, has rules banning private probation companies from collecting court costs and restitution, though they can assist the court by monitoring payment and reporting progress.[27]

In many jurisdictions, private probation companies also supervise defendants on pre-trial release or in diversion programs.

Outsourcing probation supervision appears attractive to many state and local governments because it offers a way to cut operation costs while improving collections of fees and fines.[28] Small jurisdictions may find it expensive to maintain a probation system for their own limited caseload, while private probation companies can offer their services to multiple counties. There is little evidence to prove, however, that private companies save courts money or even improve collection rates.[29] Lieutenant Joe Purvis, an officer in the Giles County Sheriff’s Department in Tennessee, explained that his office is required to deliver warrants and arrest individuals who are not complying with probation requirements. He also said that he does not believe that private probation companies are any more effective than state agencies at getting people to pay their fines and fees, but that private companies cost the government less.[30]

Judges can waive probation supervision fees for those who cannot afford to pay, even when supervised by a private company. However, this is usually left to the discretion of the judge or probation company, and rarely requires consideration of objective factors, such as employment status or income of the probationer.[31] When observing court proceedings for this report, Human Rights Watch saw situations in every state researched where even though a court determined that a probationer was indigent for the purposes of appointing a public defender, it did not waive, or even reduce, their supervision fees or other costs.[32] Judges and defense attorneys interviewed for this report consistently said that private probation fees are seldom waived. Judges expressed concern that waiving private probation supervision fees would negatively impact the companies as they rely on these fees to operate.[33] Defense attorneys reported that supervision fees for felony offenders, which are almost always handled by state probation agencies, were much more likely to be waived than in misdemeanor cases. The perverse result is that misdemeanor offenders can end up paying more for probation supervision than felony offenders.[34]

|

Kentucky: Regulation without Oversight In 2000 Kentucky created relatively comprehensive regulations of private probation companies through amendments to the Supreme Court Rules, which clearly outlined that private probation companies should only be used when probation supervision cannot be performed by a government agency, a non-profit group, or volunteers.[35] The Kentucky regulations set guidelines for avoiding conflict of interest for judges assigning defendants to supervision by a private company, provided for pro bono and sliding scale fee cases, established court oversight of fee schedules, prohibited the collection of court costs and fines by private probation, removed any discretion of probation officers over terms or conditions of probation, and ensured that employees of private probation companies do not sit in the section of the courtroom reserved for attorneys, court personnel, and litigants (or “the bar”).[36] The rules were amended in 2016 to include more comprehensive reporting requirements by private probation companies to district courts, establish confidential complaint mechanisms, and assure that probation is never revoked for inability to pay fees.[37] Though the rules do not encompass all aspects of transparency, regulation, and oversight, they do provide some of the most robust rules compared to the other states researched for this report. When the amended rules went into effect in January 2017, at least five counties chose to end their use of it Kentucky Alternative Programs II, Inc. (KAP), the largest private probation company in Kentucky. Surprisingly, the judges in these counties discontinued private probation supervision not as a result of the 2016 amendments, but rather the realization that such regulations existed at all. Though these rules had been in place for 17 years, judges had either not been aware of their existence in the Supreme Court Rules or had failed to implement them. In an interview with local media, one judge cited the requirement created in 2000 to only use private probation as a last resort alternative for monitoring supervision as the reason behind his decision to stop using KAP in 2017.[38] The county prosecutor in Lincoln County indicated that the decision may have had something to do with the sliding scale fee requirement.[39] Though these measures had been in the rules for 17 years, lack of state oversight and enforcement meant they had not been implemented. Though some judges in the state have taken note of the rules and adjusted their practices accordingly, Human Rights Watch observed continued violation of the rules in 2017 by a number of judges. It was not uncommon to see private probation officers attending court in front of the bar. Interviews with public defenders and prosecutors revealed that some judges used private agency supervision in almost all cases involving misdemeanor probation, without consideration of non-profit, volunteer, or government agency alternatives. One local lawyer in Shelbyville, Kentucky, said that alternatives to private probation had never been part of the consideration, and that an earlier competing probation agency had been forced to close operations.[40] Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Kentucky sent requests to 100 county judges across the state for information on the private probation practices they are meant to oversee.[41] Approximately 70 judges responded in either writing or by phone.[42] Responses highlighted the gaps in oversight. For example, in their responses judges provided lists of clients to whom they provide free, or reduced, sliding scale fees that the private probation companies submitted on a monthly basis. Under Kentucky law, these lists should include all pro bono clients referred to the private probation company by that district court. However, the lists were not specific to the responding judge’s jurisdiction, they were the same across counties and districts, including many clients not from the responding judge’s jurisdiction, creating misleading information about how many individuals are actually receiving free probation supervision services in each jurisdiction. In addition, the KAP pro bono list contained only nine names in April 2017, and eight unique names in May 2017.[43] At that time KAP operated in at least 15 counties and supervises thousands of clients, but fewer than 10 of their current clients had had their fees fully waived. Several counties using KAP did not have a single pro bono client. No judge provided information on rejections of pro bono referrals, meaning the judge made no pro bono recommendations or the information was not provided. In their responses to records requests, not a single judge or clerk flagged this issue in KAP’s reporting. This report argues that state governments and courts using private probation must adopt robust regulations and practices. While states like Kentucky have taken an important first step by creating rules, without monitoring and oversight, rules will not have the intended effect of protecting probationers from potentially abusive private probation practices. |

Inherent Conflicts of Interest

Private probation companies rely on the fees paid by people on probation, potentially creating incentives for companies to increase the number of paying clients and extend the period of time that probationers are supervised. Conversely, the system does not incentivize reduced fees or waivers to ensure that poor individuals can actually afford to pay expenses; any such reductions mean that the company loses revenue. Probation companies also profit from other services, such as monitoring devices, courses, and drug testing, which can create real and perceived conflicts of interest if private probation officers have any discretion in recommending or requiring these services.

The role of private probation companies in recommending sanctions for violations of probation also gives rise to the perception of conflicts of interest, particularly when it involves longer supervision periods or additional conditions that materially benefit the company.[44] In a Bay County, Florida, court, Human Rights Watch observed defense attorneys and public defenders negotiate sanctions for probation violations with a company’s private probation officers, followed by a simple sign-off by the prosecutor and judge. In other courts in Missouri and Tennessee, Human Rights Watch observed private probation officers testify in probation revocation hearings. This gives immense power to private probation officers, who stand to benefit both their companies and themselves with their recommendations for sanctions on violations of probation.

Courts’ reliance on fines and fees can also raise questions of conflicts of interest. An examination of the issue by the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan law and policy institute, noted that “when courts are over-dependent on fees, such reliance can interfere with the judiciary’s independent constitutional role, divert courts’ attention away from their essential functions, and, in its most extreme form, threaten the impartiality of judges and other court personnel with institutional, pecuniary incentives.”[45]

Major Private Probation Companies in Florida, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee

Many private probation companies are small operations, serving anywhere from one to a handful of counties, with a few notable exceptions in Florida and Kentucky. It is very difficult to get information about the industry as transparency around companies and their operations differs by state but is largely limited to voluntarily disclosed information. While government agencies generally have to provide certain public records under freedom of information laws, private companies, including private probation companies, are often exempt from these mandatory disclosures.[46]

Policies and practices vary drastically between companies. For example, one Missouri company reported a sliding scale for clients who are indigent or on disability payments.[47] PSI Probation and Tennessee Correctional Services (TCS), both in Tennessee, implemented policies to ensure that payments owed to the court, including fines, fees, and restitution, are paid directly to the clerk, even though it is not required under state law.[48] TCS stated, in response to a Human Rights Watch questionnaire, that they did not adhere to directives to file probation violations for failure to pay court costs, fines, or program fees, in part because “it would have been the wrong thing to do,” and in part because it was unlikely that local judges would have issued arrest warrants solely for a failure to pay violation.[49] Some private probation officers and owners have expressed concerns about the financial element of private probation.[50] While some companies are taking steps to address the worst abuses of the private probation system, other companies are not. The recommendations in this report are aimed at creating rules and regulations that prevent abuses across the industry.

Florida

A full list of private and government probation agencies operating in Florida is maintained by a non-profit organization, which it makes publicly available.[51] While many counties in Florida rely on county agencies or sheriff’s offices to supervise all probation, a number also refer probationers to private entities, including non-profits like the Salvation Army and the Advocate Program.[52] Two of the main for-profit probation companies operating in Florida are Judicial Correction Services, LLC and Professional Probation Services, Inc., both of which also operate in Georgia.[53] The two companies have recently come under common ownership, while still operating under separate names, creating the largest private probation company in Florida.[54] Florida Probation Service is a smaller company serving Bay, Gulf, and Jefferson Counties.[55]

Kentucky

Kentucky similarly does not publish a full list of the companies operating in the state. Human Rights Watch, in partnership with the ACLU of Kentucky, requested private probation records from nearly all county judges in the state (more information available in Appendix VII).[56] Based on the responses to that request, it is clear that Kentucky Alternative Programs II, Inc. (KAP) is the largest private probation company in the state, operating in approximately 15 counties.[57] Other companies operating in Kentucky include CDS Monitoring, Inc., Commonwealth Mediation Services, Inc., Southern Kentucky Monitoring Services, LLC, Time Out Community Counseling and Correctional Services, LLC, and You Turn Court Monitoring Service, LLC.

Missouri

Missouri also does not publish a full list of probation companies operating in the state. Local operations serving one or two counties seem to predominate. The Missouri companies primarily discussed in this report are Private Correctional Services, LLC in Cape Girardeau County and Supervised Probation Services, LLC in Pike County, but others include at least three companies bearing the name Private Probation Service in different parts of the state,[58] as well as Outreach Consulting and Counseling Services, Inc.,[59] Eastern Missouri Alternative Sentencing Services, Inc.,[60] and Court Probationary Services, Inc.,[61] among others.

Tennessee

While Tennessee requires private probation companies to obtain permits to operate, the state does not publish information on where companies are operating. Since 2005 Tennessee has issued approximately 75 permits to private probation companies, though only 33 were active as of January 2018.[62] Community Probation Services, LLC and Probation Services Incorporated both operate in Giles County and are described in greater detail in this report.[63]

|

The Scale of Private Probation in Tennessee Tennessee gathers information on how many people private probation companies supervise every year, in part because the state oversight agency, the Private Probation Services Council (PPSC), charges probation agencies a licensing fee per probationer every quarter.[64] Based on PPSC’s records of its licensing revenue, Human Rights Watch was able to calculate the average number of people under private probation supervision every year, provided in the table below. Tennessee state statistics on criminal convictions do not differentiate between misdemeanors and felonies, but the total number of post-trial convictions and guilty pleas are provided in the third column as a reference. |

|

Fiscal Year (July 1 – June 30) |

Average # of private probationers |

Total criminal cases (felony and misdemeanor) with guilty pleas or convictions[65] |

|

FY 05-06 |

29,966 |

81,208 |

|

FY 06-07 |

30,749 |

86,607 |

|

FY 07-08 |

31,565 |

87,236 |

|

FY 08-09 |

29,651 |

86,237 |

|

FY 09-10 |

34,432 |

84,332 |

|

FY 10-11 |

34,572 |

87,904 |

|

FY 11-12 |

33,096 |

89,274 |

|

FY 12-13 |

32,661 |

86,053 |

|

FY 13-14 |

31,787 |

81,130 |

|

FY 14-15 |

31,515 |

78,447 |

II. The Heavy Burden of Private Probation

Probation is an alternative to incarceration, particularly for minor crimes and nonviolent offenses. Probation allows individuals to reduce their time in jail, stay in their homes, keep their jobs, retain custody of children, and continue their lives while under supervision.[66] The objectives of probation include ensuring that the individual does not offend again, has access to the necessary treatment and support for rehabilitation, and pays restitution to any victims of the crime.[67] Since it allows individuals to remain at liberty, probation can be particularly crucial to prevent financial ruin for individuals living in poverty.

However, when probation is accompanied by excessive costs and conditions, it can quickly become a destabilizing force, undermining the intended objectives.[68] Individuals with adequate financial resources to pay court costs, probation fees, and the costs of additional probation conditions will not face the same challenges as an individual living in poverty, who may not be able to comply with probation conditions, and thereafter face arrest, probation revocation hearings, incarceration, and the long-term professional and personal consequences of a longer criminal record.[69] Private probation, without adequate regulation and oversight, can push the poor into indebtedness and have escalating consequences, including criminal repercussions, for failure to pay and meet conditions —fostering conditions for recidivism.

Probation companies have no incentive to provide meaningful rehabilitative services for which they do not receive a fee, such as supporting probationers to find housing, employment, transportation, child care, or mental health services. Quarterly reports from PSI Probation in Giles County, Tennessee, state that company probation officers allocate only 30 minutes per active client per month.[70] Probationers interviewed for this report said they spent 15 minutes or less speaking with their probation officer, and did not receive any form of support or advice for their daily needs. In Dyer County, Tennessee, outreach from local religious missions to probation officers has resulted in partnership to provide basic services, like transportation, job search resources, drug treatment, and other community services, but none is provided by private probation directly.[71]

No Choice in the Matter

Criminal defendants often settle their cases through guilty pleas, which can include private probation supervision. Misdemeanor defendants rarely benefit from the full judicial process, with the vast majority of misdemeanor convictions being reached through plea agreements.[72] Plea deals can be beneficial in some cases, saving both the defendant and court system time and resources. However, the pressure to accept a plea deal and the inability to negotiate specific terms, such as the cost and conditions associated with private probation, can lead to unjust outcomes.[73] In addition, when a defendant is pressured to accept a plea agreement, regardless of whether it includes an admission of guilt, it often creates a criminal record that has long lasting implications on employment, housing, and access to government services.

Prosecutors have a great deal of discretion in formulating and offering plea deals. In many misdemeanor courts processing large numbers of cases every day, prosecutors will offer “standard deals,” and in the four states researched, this typically includes probation when the offense carried the possibility of jail time.[74] In many of the counties in these four states, criminal defendants have only two options: supervision by a private probation company, with all the associated costs, or going to jail. If probation is part of the plea deal, the defendant must accept private supervision. This is often incorporated into contracts with private probation companies. For example, Cape Girardeau County in Missouri has a contract with Private Correctional Services, LLC (PCS) that states that the judicial district “shall utilize PCS as an exclusive provider for all above Probationary and Pre-Trial services and programs.”[75] While some counties may have contracts with multiple private probation agencies, like Pulaski County in Tennessee, which employs two private probation companies, defendants are still faced with the choice of supervision by a private company or incarceration.

Kentucky law requires courts to consider alternatives before assigning a person to private probation supervision, but lawyers practicing in Kentucky told Human Rights Watch that the standard practice was to put everyone on private probation, often through a plea deal.[76] Courtroom observation in Shelbyville, Kentucky confirmed this prosecutorial approach: in a marijuana possession case, the prosecutor informed the defendant of the minimum jail sentence and $250 fine, and then offered probation in place of the sentence and fine, arguing that probation would likely cost her less than the $250 fine. No one explained to the defendant, however, the various monetary and financial requirements of probation before she accepted the plea deal.[77] While prosecutors may think they are offering defendants the best deal, defendants themselves are in the best position to assess and weigh in the balance the time and resources required to successfully comply with probation terms, and the potentially severe consequences of violating those terms.[78]

Many counties rely heavily on plea deals to settle misdemeanor cases. In Cape Girardeau County, Missouri, misdemeanor defendants pleaded guilty in 80 percent of cases, compared to the 1 percent who go to trial and 18 percent whose cases are dismissed in FY 2016.[79] The Missouri state average for misdemeanors settled by a guilty plea was 62 percent, compared to 1 percent by trial in FY 2016.[80] In Bay County, Florida, of the 6,467 county misdemeanor cases disposed of in calendar year 2015, 3,535 — or about 55 percent — are settled in a guilty plea before trial. Only 15 cases went to trial, with 10 reaching a final verdict by trial. The remainder were dismissed or a plea agreement was reached during trial before its conclusion.[81] The Florida state average for county misdemeanors settled by plea agreement in the same time period was 57.3 percent, with nearly 30 percent of cases dismissed.[82] Tennessee statistics do not differentiate between misdemeanor and felony cases, but for all Giles County criminal cases in FY 2015, 62 percent were resolved through guilty pleas, 33 percent were dismissed, and only two cases went to trial.[83] The Tennessee state average for guilty pleas in county court criminal cases was 45.9 percent in FY 2015-2016.[84]

The choice to accept a plea deal is influenced by multiple factors. Misdemeanor defendants, whether guilty or not, are in the difficult position of either risking trial, including all the associated costs and fees and the possibility of incarceration, or choosing release under court-imposed conditions. A trial and possible incarceration could also negatively affect employment, housing, and family obligations. Many individuals therefore elect to take a guilty plea and private probation supervision, yet often without complete information about the future financial burden that it carries.[85] Statistics on the number and rate of misdemeanor offenders supervised by private probation are not available. However, all the probationers interviewed for this report stated that to avoid a lengthy and expensive trial and/or serving the full sentence, they had no choice but to accept probation and its accompanying conditions and fees.

The financial choice between probation and incarceration becomes even starker in jurisdictions with “pay-to-stay” or jail boarding arrangements, whereby an inmate can be charged for time in jail. Jail boarding fees are permitted in Florida,[86] Kentucky,[87] Missouri,[88] and Tennessee,[89] with requirements varying on taking the individual’s ability to pay into consideration. In Cape Girardeau County, Missouri, the county court regularly charges $22.50 for every night a defendant spends in jail. Giles County, Tennessee, charges both a $25 jail fee and a $25 jail building tax. Kentucky defendants are told that they can “sit up,” or substitute, certain court costs and fines with jail time at the rate of $50/day, but must also pay a jail boarding fee of $20-$30/day.[90] Kentucky also offers defendants concerned about losing their jobs the option to serve jail sentences on weekends, one or two days at a time, but they may have to pay extra for that option.[91] Boarding fees can be assessed for pre-conviction jail time, and do not include the cost of purchasing basic toiletries, telephone calls, and other commissary expenses.[92]

Defendants find themselves between a rock and hard place when “choosing” between a trial with numerous court fees and possible jail time with boarding fees, or taking a plea deal with private probation and other conditions attached. This creates steady demand for private probation companies.

Onerous Costs of Private Probation Supervision

The cost of private probation often has a profound impact on individuals struggling to make ends meet. In addition to monthly supervision fees, probation may include myriad other requirements, such as drug testing, courses, treatment, or community service, all of which carry additional fees and costs. Probation companies may also charge a variety of administrative fees for enrollment, reinstatement, records, and late or partial payment fees. These same fees can have wildly different impacts for people depending on their income. Those with lower incomes may give up basic needs, like food, housing, childcare, and medical care, in order to pay fees.[93]

In the states researched for this report, private probation monthly supervision fees generally run between $30 and $60, varying by state, county, and individual. This fee is assessed by the private probation company and may not always appear in official court documents, but payment is generally a condition of probation. Private probation companies may also apply surcharges, like start-up and reinstatement fees, ranging anywhere from $10-$25. Individuals who are unable to pay the full amount of their court costs may be put on a payment plan, whose installments are paid alongside probation fees. In some states, private probation companies also collect court costs and restitution for the courts, in addition to fees owed directly to probation companies, and may have the discretion to apply payments to different requirements as they see fit.[94] In Tennessee and Florida, some private probation companies have ensured that offenders pay company supervision fees first, before fines and fees owed to the court.[95]

Avoiding further criminal activity is a common condition of probation.[96] Probationers may be required to report any contact with the police to their probation officers, though in general only a new criminal charge would result in a probation violation.[97] In Kentucky a common condition of probation requires probationers to obtain a periodic criminal background check through the probation company. While state agencies could conduct these checks at no cost, private companies charge probationers for the service.[98] Kentucky Alternative Programs charges $20 for hardcopies of criminal records, and CDS Monitoring charges $35 for each background check.[99]

In some states, the period of supervised probation may be shortened if the probationer pays off all fees, fine, and other costs. Conversely, if a person does not complete their payments within the probation period, judges may extend supervised probation until all debts are paid.[100] This means that the poorest defendants, who take the longest time to pay their court debts, will have the highest amount of supervision fees. Extending the period of time on probation also increases the likelihood that the individual will somehow violate probation terms, which may result in further fees or additional criminal consequences. Those who can pay off their debts will benefit not only from less monitoring, and fewer risks of violating, but also from fewer probation fees.

Supervision in all the states researched may include random drug testing for which the probationer must pay, even when the individual was not charged with a crime involving drugs or alcohol. Drug tests can cost $12 for simple urine analysis to between $35 and $85 for more complex tests such as independent laboratory testing to confirm positive results. According to probationers interviewed, private probation officers often conduct random drug tests themselves.

Missouri probationers supervised by Private Correctional Services told Human Rights Watch that after a positive result in a random drug test, private probation officers required them to enroll in an intensive drug testing program, in some cases also run by private companies. Probationers were required to call a hotline every morning to see if they were selected to be tested that day. Probationers reported being tested from several times a month to several times a week, incurring charges of approximately $20-$50 per test, depending on the testing facility.[101]

Courses and treatment programs are also common probation requirements. Private probation companies in Tennessee and Florida sometimes provide these courses themselves, but in all states researched for this report, they are responsible for monitoring successful completion of courses and treatment as an element of probation supervision. These programs may be critical tools for rehabilitation and preventing individuals from re-offending, but their steep cost means that only those who can afford them can benefit. For example, in Florida an individual’s driver’s license will likely be revoked after a first conviction for driving under the influence (DUI). In order to have the license reinstated, individuals are required to complete DUI school, which is often included as a condition of probation. In Bay County, DUI school costs $284 for a first offense and $430 for a second.[102] Probationers may also be required to complete a Victim Impact Panel course, which costs $49.99 in Bay County.[103] In Missouri, the comparable required course is Substance Abuse Traffic Offender Program (SATOP) for license reinstatement.[104] The SATOP assessment fee alone is $375, followed by specialized services, like the basic education program for $130 or the $1500 intensive program. While these fees may be waived by the court, most probationers interviewed who had undertaken these programs paid the full cost. More intensive treatment may also be required, such as at residential treatment facilities, and it is the responsibility of the probationer to cover the costs, either out-of-pocket or through insurance. Regulations on when intensive treatment can be ordered are often lacking or not strongly enforced. In one case, a Missouri court ordered a probationer to find and complete inpatient alcohol treatment, though for 16 months he had been wearing a continuous alcohol monitor, which according to him had showed little alcohol consumed during that time. With no apparent alcohol abuse, inpatient facilities were reluctant to accept him, he said, making it nearly impossible to comply with the court order.[105] When a probationer cannot complete a course or treatment, a private probation officer is charged with issuing a violation of probation.

In domestic violence and other violent misdemeanor offenses, judges may require defendants to complete domestic violence or anger management courses, and private probation companies may provide these services directly. The commonly mandated batterers’ intervention program may run for six months to a year, with costs ranging from $500-$1000, depending on the length set by the court.[106] These programs attempt to educate and prevent further domestic violence, with critical public safety implications. However, the steep costs associated with batterers’ intervention and other domestic violence programs make them not universally accessible, excluding the poorest defendants.

The use of various kinds of electronic monitoring devices may also be required under probation. They may include location monitors that restrict a probationer’s movement to specified locations like home and work; continuous alcohol monitors that track alcohol levels through sweat; and ignition interlock devices, which require breathing into a device periodically to start or keep a vehicle running. The costs of monitoring devices are among the most expensive requirements of probation, and their installation can be made a precondition to be released from jail or to drive a vehicle. They may be provided by private probation companies directly,[107] or through third-party service providers. These devices often require a one-time installation charge that can vary considerably depending on location, costing anywhere between $50 and $150, and in some cases may also require a comparable removal fee.[108] Monthly monitoring fees generally range from $400-$500.[109] Ignition interlock devices may also require monthly or bimonthly calibration, adding on another $60-$150 for every check.[110]

While states may have some restrictions on the use of monitoring devices, judges often have discretion on whether to require or extend the time period for use of these devices, increasing the associated costs. In the case of Ben, for example, he received a first-time DUI conviction, and a Missouri judge required two years of supervision with both an ignition interlock device and a continuous alcohol monitor, generally only required for a second or subsequent offense under Missouri law.[111] While the prosecutor initially requested that Ben wear the alcohol-monitoring device for 90 days, he has not been allowed to remove it since September 23, 2015, and continued to wear the ankle device as of August 2017.[112] As part of Ben’s sentence, the judge required him to spend 10 days in jail, but the alcohol-monitoring device had to be installed prior to incarceration. This meant that Ben paid $12 a day, or $120 in total, for the use of the alcohol monitoring device while in county jail, where he should not have had access to alcohol.[113] The judge also required Ben to submit to regular testing, participate in alcohol treatment programs, and pay boarding fees for his 10 days in jail. Ben estimates that he has paid over $13,000 as of March 2017 for all the required conditions of his probation, apart from court costs, fines, and supervision fees. In January 2017, Ben was found to be in violation of the terms of his probation for consuming alcohol.[114] His probation was reset for an additional two years, carrying all the same conditions as his initial probation, meaning that he may have to wear and pay for the continuous alcohol monitoring and ignition interlock devices for over three years.

Monitoring devices can serve an important purpose in preventing intoxication and driving under the influence, potentially saving lives. Yet the prohibitive costs of using them mean that the freedoms these devices afford are only available to those who can pay. Ben could afford to pay and therefore did not serve a full sentence in jail or lose the ability to drive his vehicle. Those who cannot afford these payments may have to find alternative transportation options, or serve their full jail sentences. In Ben’s case, a Class B misdemeanor in Missouri, a full sentence would have carried a maximum sentence of six months in jail.[115]

Even community service requirements, often included as a probation term, may carry costs. In some states, private supervision companies charge probationers a fee to arrange and supervise community service or provide “community service insurance.”[116] Some states, such as Florida, offer the ability to substitute court costs with community service or work programs. However, these programs often do not cover all costs, like public defender’s and prosecutor’s fees, nor do they cover fees paid to private agencies, like probation supervision, drug testing, and courses or treatment. While regulations call for disabilities to be accommodated under these programs, Human Rights Watch interviewed some probationers with disabilities who felt unable to fulfill the duties assigned to them.[117] In other cases, court costs were so high that fulfilling them through community service alternatives would have interfered with the probationers’ ability to maintain their jobs. In one case in Bollinger County, Missouri, a first-time misdemeanor offender who was unable to pay his court costs was authorized to substitute them with community service, but was ordered to complete 101 hours within 21 days.[118] At over 30 hours of community service a week, combining community service with a job would be extremely difficult. An employer in Bowling Green, Missouri, described the demanding schedule of one of her employees who is currently under private probation supervision: child care, a full-time job, regular supervision visits, court mandated courses and treatment, community service hours, and if delinquent in payments or other conditions, court dates to address violations of probation. While some employers may be understanding, these demands on a probationer’s time make it difficult to be a consistent employee and some struggle to keep their jobs, leading probationers to conclude that the system is structured to make them fail. A probationer in Missouri making $8 an hour and struggling to make payments for private probation and drug testing said: “They’re trying to make sure you go to jail.”[119] Another former probationer in Tennessee described the system:

I think that the system is set up for you to fail, because I do feel that way. I do. Once you get in there, it's like a never-ending cycle. It just keeps going. Once you get on probation, especially, it's one fee after another and if you can't pay then you go to jail, and then once you're in jail and then you get out, you have more court fees, and them more fees, and more, and more, and more. It never ends, and that's why some people would just rather go to jail and just deal with it that way.[120]

|

What’s the Alternative? Privatizing probation is not the only option available to local courts. If state level agencies are unable or unwilling to supervise misdemeanor and traffic offenders, other public agencies can take their place. Roughly half of Florida counties rely on their sheriff’s offices or county probation offices for these services.[121] Some counties in Kentucky rely on court clerks, county attorney’s offices, or Probation and Parole, which generally handles felony cases, to supervise misdemeanor probation, often with lower supervision fees than private agencies.[122] Other Kentucky counties do not require any type of supervision for misdemeanor or traffic probation, and therefore do not require probationers to pay any type of supervision fees. A judge in Daviess County, for example, requires that probationers not get any more criminal charges or fail to make payments toward their court costs, but instead of requiring probation these terms are monitored through periodic court hearings.[123] Differences in the approach to probation supervision mean highly divergent outcomes for individuals facing similar charges in the same state or even county. Within Daviess County, for example, one judge does not use private probation, while another judge uses Kentucky Alternative Programs to supervise some probationers. Depending on what county a person is charged in, or which judge decides their case, the financial outcomes for the same crime can vary substantively based on whether they are sentenced to supervised or unsupervised probation.[124] |

No Relief Available