When Akanni’s mother died in early 2018, she stopped eating for three weeks. Her mood became unpredictable; she was often shouting or sulking angrily. Medicine from a local pharmacist didn’t help. At a loss for what to do to handle the trauma, Akanni’s father took her to a church in Abeokuta, Ogun state, in Nigeria. And then he left her there.

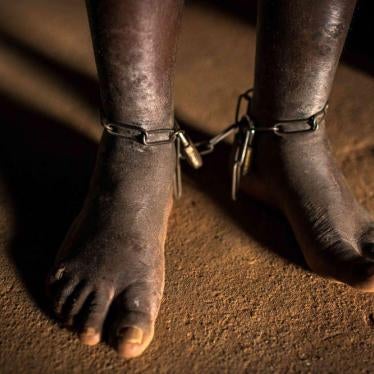

The evangelist in the church chained her in a room, where she was left on a bare floor for three days straight with no food or water. She stayed there with a man who was going through a mental health crisis. She felt alone. The staff gave Akanni a pot to urinate and defecate in, right in front of the man.

Akanni is still imprisoned in the church. She is deprived of food and water every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday until 6 p.m. The staff at church claim this is for fasting purposes as part of her treatment. When she resists, they chain her again. “Sometimes if they say I should fast and I drink water or take food, they put me on chain,” she told our researchers. “The chaining is punishment. I have been put on chain so many times, I can’t count.”

Akanni is not alone. Human Rights Watch documented that thousands of people with actual or perceived mental health conditions across Nigeria are chained and locked up in various facilities, including state-owned rehabilitation centers, psychiatric hospitals, and faith-based and traditional healing centers. Many are shackled with iron chains, around one or both ankles, to heavy objects or to other detainees, in some cases for months or years.

Chaining is a global human rights issue. Human Rights Watch has documented its use in numerous countries, including Indonesia, Ghana, Somaliland, and most recently Nigeria.

Like Akanni, people cannot leave these facilities, and are confined in overcrowded, unhygienic conditions, and forced to sleep, eat, and defecate within the same confined place. Many are physically and emotionally abused and forced to take questionable treatments.

People are chained for a range of reasons: when they behave outside what’s considered “the norm,” are going through trauma or grief, or even for getting upset. Like Akanni, who never had access to mental health professionals before her father abandoned her at the church, most Nigerians are unable to get adequate mental health services or support in their communities and rely on traditional and religious healers for support. Stigma and misunderstanding, specifically ideas that mental health conditions are caused by evil spirits or supernatural forces, drive relatives to take their loved ones anywhere the relatives think their loved ones could get help.

Signs of light are appearing. In October, President Muhammadu Buhari denounced chaining as torture, and the Nigerian police carried out raids in Islamic rehabilitation centers in the northern part of the country. Although the Nigerian Constitution prohibits torture and other inhuman or degrading treatment, the government has yet to outlaw chaining people with mental health conditions. The government has also yet to acknowledge that chaining is happening in government-run facilities as well as traditional and other religious centers that are not Islamic.

And today, as the world and Nigeria grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s even more necessary than ever to end this practice, free people from chains, and ban shackling forever.

Banning chaining is just the first step. It’s also necessary to monitor and meaningfully enforce the ban. Further, it’s essential to prioritize providing psychosocial support and mental health services as close as possible to people’s own communities. Humane and accessible care need not be extraordinarily expensive. To give one example, cities and countries around the world are now following the Zimbabwean model of the “Friendship Bench,” a community-led initiative that trains and supports older women to offer talk therapy and make connections to vital social services and mental health care.

Article 5 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights is clear that “no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

But this is more than a violation of the law. When asked what’s worst about being in the church, Akanni was unequivocal. “I feel lonely,” she said. Chaining represents the most extreme imaginable denial of our fundamental human rights. It strips people of the basic need to belong, connect with community, have a home, learn, express one’s self, have agency. It’s an affront to the essence of what makes us human.

Akanni recently told Human Rights Watch about her hopes and dreams. She wants to go home, study accounting, get a job, and lead a healthy and joyful life. It’s up to President Buhari, leaders and civil society in Nigeria, and all of us who can exert pressure around the world, to see that she and countless others have a meaningful chance to realize these dreams.