Racial and ethnic profiling by the Moscow police is a problem so old that it’s simply not news. But rarely do you catch police acknowledging it on camera.

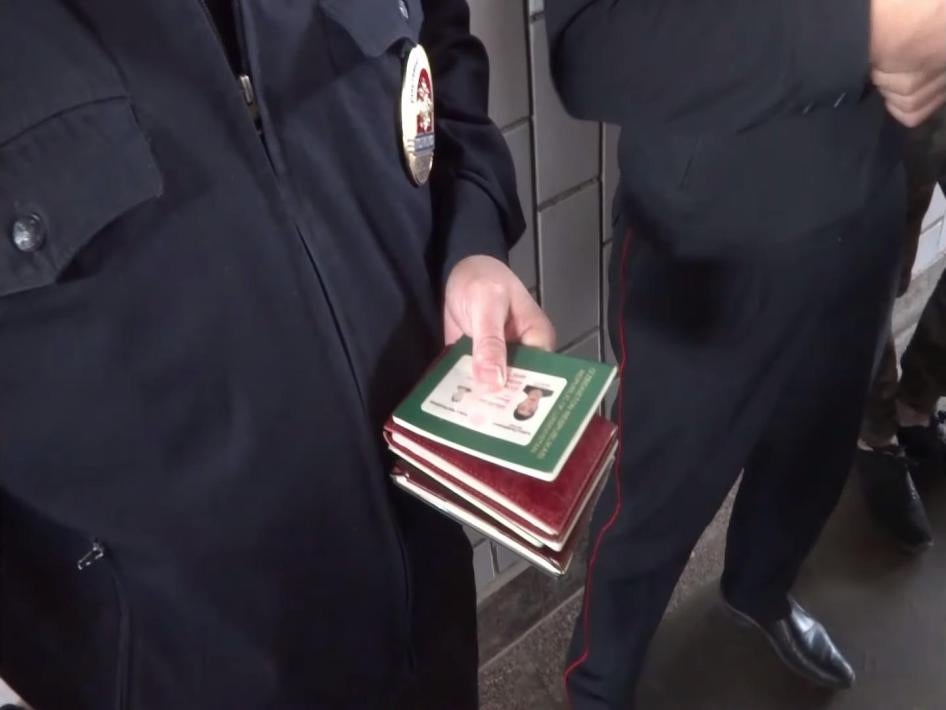

Alexander Kim did just that. Kim told me that he was walking through an underground passage in southern Moscow on 20 July when he saw several police officers holding a batch of passports, with a number of men who looked Central Asian standing nearby. Kim started recording with his phone and asked the police why they confiscated the passports. The police responded, “and who are you?”

I watched Kim’s video, which shows police asking to see Kim’s identity papers. When asked why, an officer referred to an alleged, ongoing “Special Operation--‘Illegal,”, and said that based on Kim’s looks, he thought Kim “might not be a Russian citizen.” When Kim asked why they didn’t check other passers-by, the officer replied, “because you look Asian.”

The officer denied this was discrimination, yet continued to insist that Kim show his papers because of his Asian looks.

A Russian citizen, Kim could challenge the police without risking deportation. He insisted that the police identify themselves, in line with the law. But eventually the police put all the men in a police vehicle, including Kim. When they noticed that Kim continued filming, they ordered him to leave. When he hesitated, noting that police had wanted to check his ID, they detained him for disobeying police orders.

Police held Kim with two of the other men for two nights in a sealed windowless cell with the lights on around the clock, giving them only one set of sheets to share. Kim was only given one glass of tea once a day to drink along with some food that he described as inedible. After being held in such inhuman and degrading conditions, he was taken before a judge, who fined him 1,000 roubles (about US$15) for disobeying the police without granting any motions or considering arguments in his defense.

This wasn’t Kim’s first encounter with racial profiling. He said that in 2017, Moscow police stopped him for an ID check, openly citing his Asian appearance as grounds. To Kim, it felt like obvious discrimination, so he refused to show his ID. Police detained him for disobedience, breaking his finger in the process. He was fined that time too, and the court also refused to take into account any of his arguments. His case about that incident is pending before the European Court of Human Rights.

In April, once again, he spent about five hours at a police station after refusing to show his ID to police who stopped him due to his looks. He was released without charge.

None of his complaints about police conduct in those episodes yielded any results.

Kim experienced two more episodes of racial profiling this year, but the police didn’t detain him on those occasions after he quoted the law and demanded to be informed of the legal grounds for checking his documents.

Valentina Chupik, an expert on migrants’ rights and Kim’s public defender, told me that special police operations target non-Slav migrants regularly. But there’s no transparency about what instructions police receive, so it’s hard to know whether they would fall afoul of anti-discrimination standards in international and domestic law.

Sadly, Chupik said, those caught up in racial profiling - non-Slavs, including Russian nationals - are commonly subjected to ill-treatment and are often extorted for bribes for their release. She described an episode last New Year’s Eve when several hundred non-Slavic-looking men, most from Central Asia, were detained by police in central Moscow. About 100 of them were left locked inside unheated buses in front of a police station all night. She and several other lawyers spent most of the night trying to provide legal assistance to those rounded up.

Yet, unlike Kim, none formally complained because doing so could put them at risk of deportation and being banned from re-entering the country for several years. Many are likely migrant workers whose families depend on remittances from Russia.

Non-Slav migrants are some of the most vulnerable and voiceless people in Russia today, and their ordeals commonly fall under the radar.

But something else that happened on the day of Kim’s detention offers some hope that public scrutiny of such episodes may make a difference.

It was a similar racial profiling incident, but with a very different outcome. Police in central Moscow approached several Central Asian men, demanded their passports and then wanted to take them to a police station. Several passers-by filmed the episode, including human rights activist Irina Yatsenko, who streamed it and used her privilege to defend the men’s rights. When Yatsenko insisted that police explain the legal grounds for their actions, police referred to the same “Special Operation—‘Illegal.’”

After a gathering crowd intervened, the officer returned the men’s passports and reluctantly agreed to check the men against a database on the spot rather than at the police station. And finally, albeit without explanation or apology, the police left the men alone.