Equatorial Guinea will undergo its peer review before the UN Human Rights Council, known as the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), on May 13, 2019. The UPR allows the governments that sit on the council to scrutinize each country’s human rights record every four years and make recommendations for improvement.

“Governments should seize the opportunity of the peer review to carefully scrutinize the human rights record of Equatorial Guinea, currently a member of the UN Security Council, including its track record of intimidating, imprisoning, and torturing critics of the government,” said Sarah Saadoun, Business and Human Rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “An artist, a teacher, a human rights defender – these are some examples of people the government has targeted.”

Human Rights Watch has documented numerous cases of retaliation against activists and political opposition members in Equatorial Guinea, including harassment, arbitrary detention, ill treatment, and torture. These include dozens of cases in which detainees were denied basic due process rights, such as access to legal representation and being charged with a crime. The government has not investigated or held anyone accountable for these abuses.

Governments should express serious concern about these abuses and press the Equatorial Guinean government to:

- Respect citizens’ freedom of expression and political opinion;

- Ensure the independence of the judiciary and respect due process rights of anyone in custody;

- Produce a comprehensive list of political prisoners and provide information on the whereabouts of all prisoners;

- Permit independent monitors, such as the UN special rapporteur on freedom of expression and UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, to visit the country and provide them with access to prisons and detention centers; and

- Use its available resources to ensure proper funding for education, health, water, and sanitation.

The suppression of criticism and dissent has helped President Teodoro Obiang to remain in power for 40 years, making him the longest serving president in the world. Obiang, his family, and other members of the ruling elite have plundered the nation’s oil wealth, while investing little in improving access to health care and primary education for the vast majority of Equatorial Guineans.

In 2016, Obiang appointed his son, Teodorin Nguema Obiang, vice president, putting him next in line for the presidency should his 80-year-old father resign, become incapacitated, or die. In October 2017, a French court convicted the son in absentia of stealing more than $120 million from the public treasury to finance a lavish lifestyle in Paris. Swiss prosecutors reached a deal with Equatorial Guinea to close a money laundering investigation into Nguema Obiang in February 2019, and the US Department of Justice settled a similar case in 2014. In a rare positive step, Equatorial Guinea, in May, ratified the United Nations Convention Against Corruption, a move the International Monetary Fund required as a pre-condition for a loan.

“The government’s brutal campaign to silence dissenting voices not only destroys the lives of those brave enough to defy it but underpins a government that has robbed many Equatoguineans of the country’s oil wealth,” Saadoun said. “Money that should have been invested in fulfilling the rights of the country’s citizens goes to yachts, planes, and mansions.”

For a sample of cases of people who have suffered abuse by the government, please see below.

Human Rights Watch, EG Justice, and other human rights organizations have documented numerous cases of Equatorial Guinean authorities’ repression of human rights defenders and the political opposition over the past decade based on interviews with victims and lawyers, legal documents, and photos. Several cases from September 2017 to March 2019 are described below. In some of these cases, authorities harassed, arrested, or mistreated people merely for criticizing the government in violation of their freedom of expression. In other cases, the arrests may have been lawful, but detainees experienced serious due process violations and ill-treatment.

Arbitrary Detention, Torture of Political Opponent

Joaquin Elo Ayeto founded Somos+, an organization to mobilize and engage young people in demanding greater accountability of the Equatoguinean government. He is a member of the political opposition party Convergencia Para la Democracia Social. On February 25, 2019, police, led by the presidential security director, arrested Elo Ayeto, apparently because, in a class, he had criticized a government project to build a church rather than invest in health and education. He had been detained twice before for apparently politically motivated reasons. Elo Ayeto told his lawyers that during the interrogation, police telephoned his classmate, who is the presidential security director’s niece, and that she repeated the comments he had made on speaker phone. Following the call, he said, police began questioning him about an alleged coup plot that he had no knowledge of.

On the second day, the police tied his hands and feet, hung him from the ceiling, and lashed his buttocks and legs, Elo Ayeto told his lawyers. Human Rights Watch viewed photographs of Elo Ayeto taken in the days after his arrest, which show markings on his body consistent with this account. On February 29, Elo Ayeto was taken before a judge, who ordered him held in preventative detention, which in Equatorial Guinea allows the government to hold someone indefinitely without charge or evidence. Elo was then transferred to Black Beach prison, where he remains.

Retaliation, Arbitrary Detention, Physical Attacks Against Human Rights Defender

Alfredo Okenve, vice president of the Center for Development Studies and Initiatives (CEID), an organization that promotes good governance and human rights in Equatorial Guinea, has for several years faced repeated reprisals for his work. From 2007 to 2017, he represented civil society in a multi-stakeholder group formed as part of the government’s bid to join the Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative, a global program that advances transparency in resource-rich countries. In March 2019, authorities prevented Okenve from leaving the country and briefly placed him under house arrest.

Six months earlier, four men, who appear to have been undercover security officials, dragged him from his car at gunpoint, drove him to a remote location, and beat him severely. In 2017, police held Okenve, along with the president of CEID, in a police station for two weeks until he agreed to pay a fine of more than US$3,000. Okenve has been unable to find employment since he was removed from two posts at the National University after criticizing the government’s transparency record at a May 2010 event in Washington, DC. A private company that agreed to hire Okenve withdrew the job offer at that time, apparently due to government pressure.

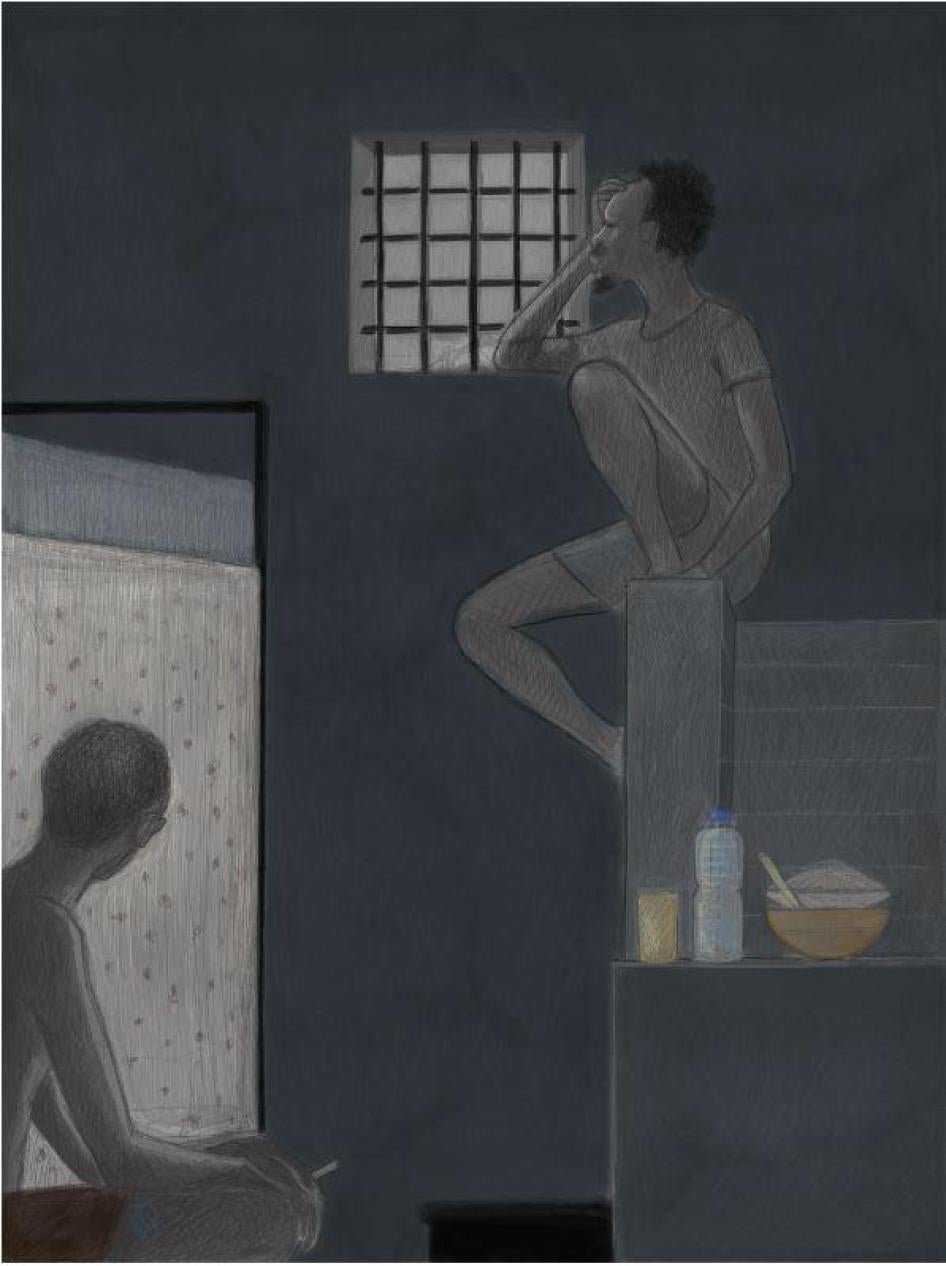

Arbitrary Detention of Artist

Ramón Esono Ebalé, an artist who lives outside the country, was arrested in Malabo on September 16, 2017, while in the country to request a new passport. Police interrogated him about his drawings, which were critical of the government.

Three months later, as he still awaited his passport, the authorities charged him with counterfeiting $1,800 in local currency. At Esono Ebalé’s trial, the police officer who had claimed to have found the counterfeit money in Esono Ebalé’s car admitted he had acted on orders of his superiors. The prosecution then withdrew the charges and he was released on March 7, 2018, after spending nearly six months in prison. The case drew widespread attention and condemnation from dozens of human rights organizations, hundreds of artists, and high-profile figures from around the world.

Arbitrary Detention of Teachers

Police arrested Julián Abaga, a teacher, on December 12, 2017, soon after an audio message he sent to a friend living abroad denouncing corruption in Equatorial Guinea was uploaded to the internet, said a news release from a political opposition party. A lawyer who met with Abaga said he was accused of “insulting the president.” He was never brought to trial, and was released on July 4, 2018 in what the government called a “gesture of goodwill,” following an event Obiang initiated that purported to bring the government into dialogue with political opposition groups.

Arbitrary Detention, Torture of Political Opposition Members

In December 2017, police arrested 147 members of Citizens for Innovation (CI), the only opposition political party with a seat in parliament. The sweep followed a confrontation in the city of Aconibe between police and CI supporters attending a rally for which it held a permit. During the confrontation, news reports said, CI members harmed three police officers, but the authorities appear to have used the incident to crack down on CI.

The police arrested dozens of CI members on December 28 at CI’s headquarters. Elvira Beba Cité, who was elected as a CI City Council member the previous month, was among them. She was not involved with the protest and was not there. While in prison, she and the others were frequently beaten and denied access to an attorney, she told Human Rights Watch.

On February 23, 2018 a court ordered CI dissolved and sentenced 21 of the detainees to 30 years in prison for “sedition” and other crimes. The court released the others, including Beba Cité. Lawyers representing some of the detainees allege that many had been tortured while they were in prison, including two who died. On October 22, Obiang pardoned those who had been convicted, along with 48 other prisoners, but without citing a reason.