Corruption, poverty, and repression of human rights continue to plague Equatorial Guinea under President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, the world’s longest serving president, who has been in power since 1979. Vast oil revenues fund lavish lifestyles for the small elite surrounding the president, while little progress has been made on improving access to key rights, including health care and primary education, for the vast majority of Equatorial Guineans. Mismanagement of public funds, credible allegations of high-level corruption and repression of civil society groups and opposition politicians, and unfair trials, persist.

In April, police detained the two leaders of the Center for Development Studies and Initiatives (CEID), the country’s leading civic group and a member of the national steering group of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), creating yet another obstacle toward the government’s stated goal of reapplying for EITI membership. EITI promotes a standard by which information on the oil, gas, and mining industry is published, requiring countries and companies to disclose key revenue information. In September, police arrested an artist whose drawings frequently lampoon government officials; he remained in detention and had not been charged at time of writing.

Equatorial Guinea won a seat on the Security Council beginning in January 2018. Its victory was assured after the United Nations’ African group submitted a non-competitive slate for the annual election of non-permanent council members. Governments and rights groups in a number of countries have initiated money-laundering investigations against government officials.

In October, President Obiang’s eldest son, Teodorin, was convicted by a French court of embezzling more than €100 million (US$119 million) in state funds to purchase a Parisian mansion, exotic sports cars, and luxury goods. In an apparent attempt to shield him from accountability, Obiang appointed Teodorin vice president in 2016, shortly after French prosecutors concluded their investigation. Another money-laundering prosecution implicating government officials is making its way through the Spanish courts, and Swiss authorities started investigating Teodorin for alleged money-laundering activities in 2016.

Economic and Social Rights

Equatorial Guinea is among the top five oil producers in sub-Saharan Africa and has a population of approximately 1 million people. According to the United Nations 2016 Human Development Report, the country had a per capita gross national income of $21,517 in 2015, the highest in Africa and more than six times the regional average.

Despite this, Equatorial Guinea ranks 135 out of 188 countries in the Human Development Index that measures social and economic development. Available data, including from the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and a 2011 joint household survey by government and ICF International, a US firm specializing in health surveys, reveal that Equatorial Guinea has failed to provide crucial basic services to its citizens.

In 2016, 42 percent of primary school age children were not registered as students, the seventh highest proportion in the world, according to UNICEF. Only half of children who begin primary school complete it. And according to the 2011 survey, about half the population lacks access to clean water and 26 percent of children exhibited stunted growth, a sign of malnutrition. Equatorial Guinea has among the world’s lowest vaccination rates; 25 percent of children received no vaccinations at all, according to the 2011 survey.

In August 2014, Equatorial Guinea reaffirmed its commitment to rejoin EITI, an initiative from which it was expelled in 2010, in part due to its failure to guarantee an “enabling environment” for civil society to fully participate in EITI’s implementation. Since then, the tripartite EITI steering committee made up of government officials, oil company representatives, and civil society has met five times, including in April and September 2017.

Freedom of Expression and Association

Only a few private media outlets exist in the country, and they are largely owned by persons close to President Obiang. Freedom of association and assembly are severely curtailed, and the government imposes restrictive conditions on the registration and operation of nongovernmental organizations. The few local activists who seek to address human rights-related issues often face intimidation, harassment, and reprisals.

On April 17, 2017, the police detained Enrique Asumu and Alfredo Okenve, who head the leading civil society group CEID. The two men visited the National Security Ministry after security officers prevented Asumu from boarding a domestic flight, apparently on the ministry’s orders. The minister interrogated them for five hours and then prevented them from leaving. Authorities did not charge them or bring them before a judge, as is required under Equatoguinean law, but, after several days’ detention, conditioned their release on a fine of 2 million CFA francs (US$3,325). Asumu, who has health problems, was released on April 25, and Okenve on May 3, after both paid the sum demanded.

The detentions are the latest in a series of government efforts to impede CEID’s work. In March 2016, the minister of interior, who also headed the National Electoral Commission, suspended the organization one week before the government called for early presidential elections. CEID resumed activities in September 2016, and prior to the detentions high-level officials attended its events and it took part in EITI meetings.

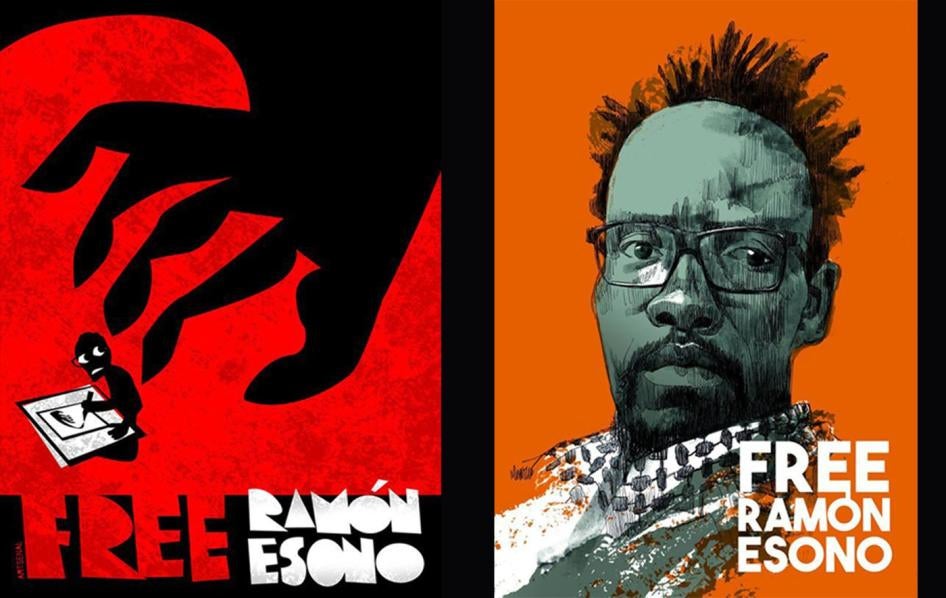

On September 16, state security arrested a political cartoonist, Ramón Nsé Esono Ebalé, whose drawings are harshly critical of President Obiang and other senior government officials. At time of writing, he remains in prison without charge.

Elections and Political Opposition

The ruling (PDGE) party’s virtual monopoly over political life and government continued in 2017, as did harassment of the political opposition. President Obiang won a new seven-year term in April 2016 in an election the US embassy in Malabo said was marred by political harassment. PDGE and aligned parties won the entire 70-seat senate in November 12 elections, and only one opposition representative won a seat in the 100-member House of Deputies. Obiang elevated his son to the position of vice president in June 2016, four weeks after French prosecutors formally requested he be brought to trial in an apparent attempt to shield him from prosecution over corruption allegations.

On June 23, police briefly detained two journalists, Samuel Obiang and Justo Enzema, while they were attending a press conference held by political opposition groups covering the French money laundering trial of Teodorin Obiang, according to EG Justice, an independent rights group. Four days later, police arrested Joaquin Elo Ayeto, a member of the opposition party Convergence for Social Democracy (CPDS) and held him for three days without charge.

Ayeto told Human Rights Watch that police accused him of inciting violence because he and others had attended the funeral of a taxi driver killed during a protest and distributed pamphlets denouncing government violence. He was also held for approximately one month without charge in December 2016, which he said was retaliation for writing an internet post about an officer he observed at a toll booth who refused to pay the toll.

International Corruption Investigations

On June 19, Teodorin Obiang was tried in absentia by a French court on charges of corruption, money-laundering, and embezzlement. He was convicted on October 27 and sentenced to a three-year suspended sentence and €30 million (US$35 million) suspended fine. During the investigation, French authorities seized assets belonging to Teodorin, including a mansion, 11 luxury cars, and a €22 million (approximately $24 million) art collection. At the time the purchases were made, Teodorin was minister of agriculture, for which he earned less than $100,000 annually. The prosecution presented evidence they claimed showed that at least €110 million (US$119 million) was transferred from the public treasury into Teodorin’s accounts.

Teodorin was not present at the trial, but his lawyers’ argued that the charges were politically motivated and that there are no domestic conflict-of-interest laws barring Teodorin from amassing such wealth from public contracts. They also claimed that Teodorin should be immune from prosecution as vice president.

Teodorin had unsuccessfully claimed immunity as second vice-president in a separate money-laundering case brought against him by the US Department of Justice following his purchase of a $30 million Malibu mansion and a $38.5 million private jet. That case was settled, with Teodorin agreeing to forfeit $30 million to US authorities that would be repatriated for the benefit of Equatoguineans. The US is expected to determine which charities will receive the funds imminently.

A Spanish judge unsealed the files in a separate corruption case implicating several senior government officials, including the president. A trial is expected in early 2018. The complaint alleges that the named officials purchased homes in Spain through a private company that a US senate investigation revealed had received $26.5 million in government funds at around the same time of the purchases. In September 2015, police arrested a Russian couple and their son who are accused of facilitating the transactions.