In the coming months, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo will be pressed to make two critical decisions that will determine whether the United States will retreat further from its global role in protecting refugees.

First, with President Donald Trump predisposed to drastically reduce refugee resettlement numbers, Secretary Pompeo will need to decide whether to try to hold the line on further deep cuts in the refugee admissions ceiling. He also will need to decide whether to resist White House pressure to eliminate the State Department’s refugee bureau.

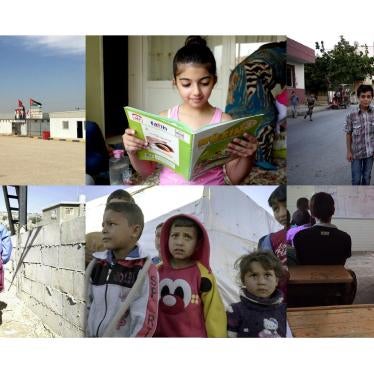

Both decisions will have implications for the world’s 25 million refugees and for the stability of the countries where most of them live, including geopolitically sensitive countries such as Turkey, Jordan, Pakistan, Ethiopia and Kenya. But these decisions also will have broader implications for U.S. foreign policy and the guiding humanitarian principles that traditionally have underpinned much of U.S. global engagement.

U.S. leadership in global refugee protection comes not only from its ranking as the top donor for refugee humanitarian response but also as the country that resettles more refugees than any other. This has been a strong bipartisan priority, one that for many lawmakers and policymakers reflects both U.S. interests and values. Because of the depth of its commitment and its history as a haven to the persecuted, the United States has been able to exert critical leadership in shoring up sometimes faltering international support for the countries on the front lines of refugee crises.

In September 2016, President Barack Obama stood before the United Nations General Assembly and pledged to resettle 110,000 refugees in the coming year, as part of his effort to leverage other countries to do more to rescue refugees and relieve the burden on countries of first arrival. But with Donald Trump coming into office after the start of fiscal year 2017, the United States resettled less than half that number — 53,716 — that year.

Then the White House set the FY 2018 ceiling at 45,000, the lowest since the passage of the Refugee Act in 1980. Despite that ceiling, the United States is on pace to resettle only 21,000 this year. President Trump’s senior adviser Stephen Miller reportedly is pushing to lower the FY 2019 ceiling to 25,000. Some reports say the president would prefer to go even lower — topping out at 5,000.

Time after time, the engine that has powered the U.S. leadership drive to mobilize international solidarity has been the State Department’s refugee bureau, whose two major functions are managing humanitarian assistance and refugee resettlement.

Media reports indicate the White House is thinking about moving the refugee bureau’s humanitarian assistance function to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and possibly moving some truncated version of its resettlement function to the Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Instead of centralizing these refugee protection functions within wider U.S. foreign policy, they instead would become part of U.S. development and immigration policies.

Donor governments’ role in the development sphere generally is to work cooperatively with the governments of underdeveloped countries to improve economies and infrastructure. The refugee reality is fundamentally about protecting refugees and meeting their humanitarian needs until durable solutions — repatriation, local integration, or resettlement — can be found. In some cases, development may be an aspect of that response, but at the root of most refugee situations are human rights violations that won’t be solved using a development model.

Furthermore, the tools and skills needed to protect refugees, at times adversarial, are not always found on the development side, where friendly relations with governments usually play a more important role than defending the rights of people living under that government’s control.

The State Department uses refugee resettlement to leverage other strategic objectives to manage refugee crises — gaining support of other resettlement countries, convincing countries of first arrival not to push refugees back — as part of a tool kit that includes funding and technical and political support. The Department of Homeland Security has no capacity or mandate to perform this function but would approach refugee resettlement largely through an immigration lens.

The larger question, of course, is whether taking the refugee bureau out of the State Department would mean more than just shuffling the bureaucracy. Would it reflect the view that candidate Trump expressed during one presidential debate — that the U.S. refugee resettlement program was a “Trojan horse” bringing terrorists into the United States? Given the evisceration of refugee resettlement since President Trump took office, there is ample reason to suspect the motivations behind reorganizing this bureau.

If these two decisions result in essentially ending refugee resettlement and forfeiting U.S. leadership in creating and maintaining asylum space in the regions of conflict, the United States would be closing the valve on the refugee pressure cooker. It would make host governments’ management of refugee populations immeasurably more difficult because it would take away the hope of resettlement that makes refugees’ years of waiting bearable.

If the United States turns its back and closes the door, that would signal to countries on the front lines that it is acceptable for them to close their doors as well, blocking the escape of people fleeing for their lives.