Authoritarian governments around the world use broadly drafted national security laws to silence human rights defenders, journalists, bloggers, and critics of the government. Australia should not join them by passing a revised espionage and foreign interference law that excludes safeguards for legitimate disclosures in the public interest.

Interference by foreign governments and their proxies is a legitimate threat to Australia, and the Government needs to address it. But it should be careful to protect the country's democratic freedoms, especially the right to freedom of opinion and expression.

Last week Australia's Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security released its 400-page report with 60 recommendations to revise the espionage and foreign interference bill.

It suggests numerous meaningful improvements. For instance, it says a "degree of damage or harm" is needed to constitute "prejudice to national security" for the espionage, foreign interference and sabotage offences and "embarrassment alone" is not enough.

The committee also made recommendations that would significantly improve the bill's secrecy provisions, recommending reduced criminal penalties and a defence for journalists acting in the public interest and those who circulate information already in the public domain.

But it's not just journalists who may fall afoul of these laws.

As drafted, so might whistle-blowers like Edward Snowden, individuals and nongovernmental organisations who expose human rights violations.

National security definition too broad

The problem is that the laws' national security definition is very expansive, including "the country's political, military or economic relations with another country or other countries".

The committee did not recommend tightening this definition. But the lack of specificity about what constitutes national security means that those who make public politically sensitive information could be guilty of espionage.

It is obviously in the public interest for the Government to keep some national security information secret. But under international human rights law, the public interest — not any particular government's interest — is crucial. The protection of national security and public order may provide legitimate reasons for not disclosing certain sensitive information, but that should never extend to suppressing disturbing information or information embarrassing to the Government.

No-one should be prosecuted for exposing human rights violations, such as leaked information about government airstrikes that killed civilians, for example. At the very least, there has to be a genuine opportunity to offer a public-interest defence.

While the Attorney-General has discretion to prosecute, that's not enough. Even if Australians think national institutions are robust enough to protect against misuse, it's putting too much faith in an executive branch that may have reasons to pursue politically motivated prosecutions.

We see this in China and Russia

It's important for Australia to get this right. Countries around the world will look with interest at Australia's new foreign interference laws. Bad laws would open the door for governments that have weak institutions and lack an independent judiciary to manipulate the laws to arbitrarily detain and wrongfully prosecute activists, journalists and critics of the government.

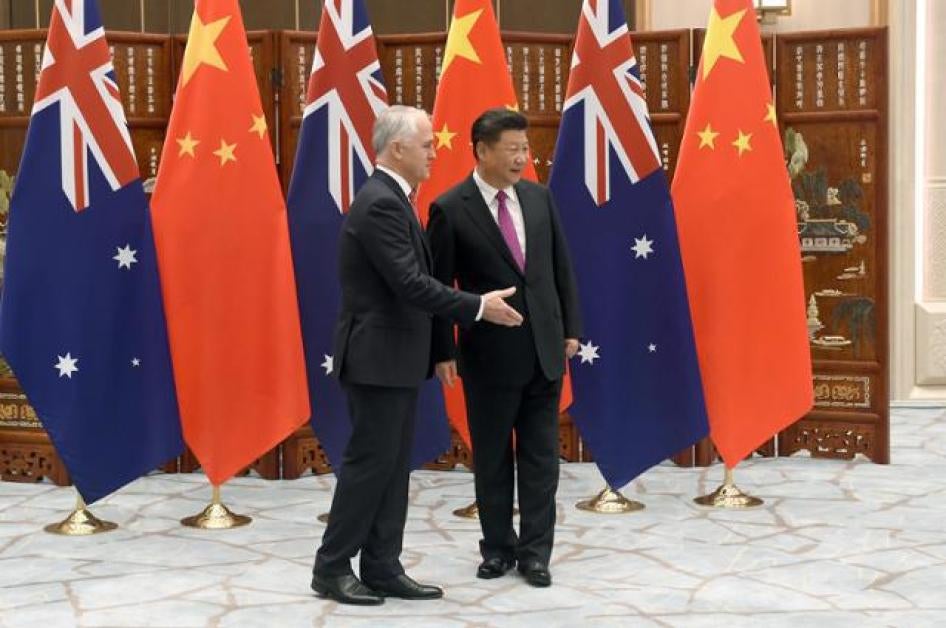

We see this happening already in China and Russia. And of course protecting Australia from governments like China and Russia is what this legislation is really about.

This debate has been driven, at least in part, by a pressing need to address the activities of entities like the United Front Work Department, a Chinese Communist Party entity that has targeted Australian politicians and Australia's Chinese community.

There is a real risk to those who have left countries with repressive governments, like China and Ethiopia. Government proxies have openly threatened and harassed them in Australia, or detained family members back home as a result of their relatives' activities in Australia.

In 2016 Human Rights Watch reported that Ethiopian Australians said that family members back home had been detained because they had participated in a protest against a visiting Ethiopian government delegation.

"I don't feel safe here," one Ethiopian Australian told us. "When I came, [I thought] now I will be in a free country. To be in Australia and be scared all the time, it doesn't go together."

Many covert activities in Australia by foreign governments will be difficult to prosecute under the new law. One thing Australian authorities could immediately do is set up a national monitor to receive and investigate complaints from diaspora communities that have struggled with getting the police to act on their complaints.

Freedom of expression is something most Australians take for granted. But it's important to make sure that curtailing improper foreign interference doesn't criminalise the actions of whistle-blowers, human rights activists, and bloggers. Passing this law without a strong public-interest defence could have a serious chilling effect on disclosing information in the public interest. Australia shouldn't aspire to insulate itself from China's political interests by becoming more like China itself.