(Sydney) – Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull should make human rights a central and public focus of the upcoming summit with Southeast Asian leaders, Human Rights Watch said in a briefing paper released today. Turnbull is scheduled to host leaders of the 10-country Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) March 17-18 in Sydney at the ASEAN-Australia Special Summit, the first ASEAN summit to be held in Australia.

“Australia’s failure to publicly raise human rights concerns at the summit would not only provide a propaganda coup to ASEAN’s most abusive leaders, it would embolden all the region’s leaders contemplating major crackdowns, jailing journalists, or dismantling democratic institutions,” said Elaine Pearson, Australia director. “Robust engagement on good governance, democracy, and human rights does not mean lecturing others, but instead discussing serious human rights issues that are critical to ASEAN governments and people.”

The briefing paper, “Human Rights in Southeast Asia,” outlines key human rights concerns in eight ASEAN countries with a focus on Australia’s role promoting rights in the region. Human Rights Watch urged the Australian government to raise specific human rights concerns at the summit, including crimes against humanity in Myanmar and the Philippines; the crackdown on the political opposition, media, and civil society in Cambodia; and restrictions on free expression in Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Singapore.

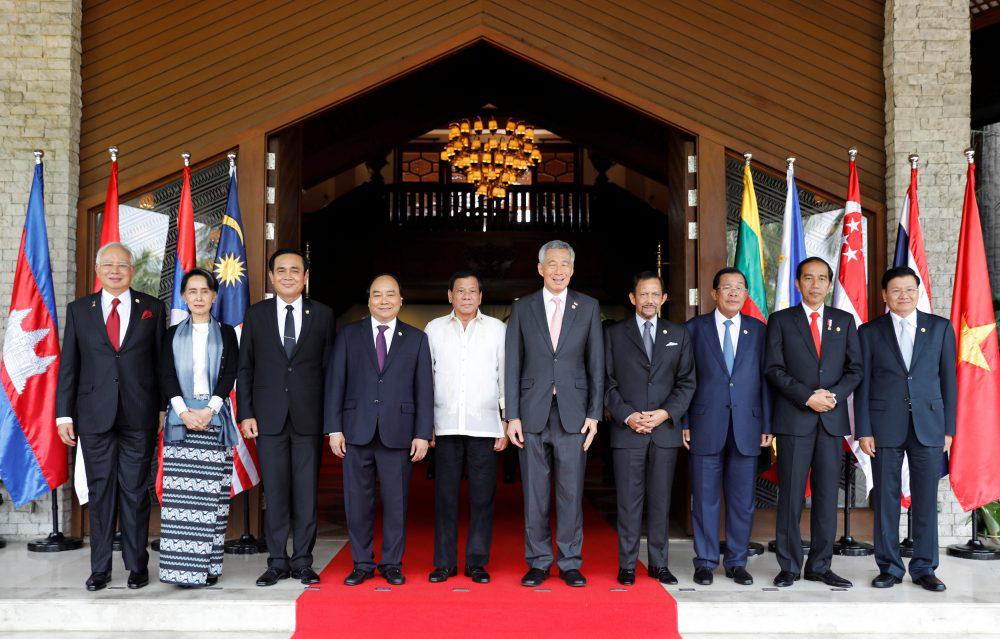

All ASEAN leaders except Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte will be attending the summit, which will be preceded by a business summit and a counterterrorism meeting. Australia is pursuing closer ties with ASEAN countries in part to counter an increasingly assertive China in the region.

Promoting human rights at the ASEAN summit is consistent with Australia’s 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper, which notes, “Australia’s national interests are best advanced by an evolution of the international system that is anchored in international law, support for the rights and freedoms in United Nations declarations, and the principles of good governance, transparency and accountability.”

In a letter sent to Prime Minister Turnbull in February, Human Rights Watch called on him to put human rights at the heart of the agenda of the summit, to facilitate civil society participation at the summit, and to communicate to ASEAN leaders that without concrete progress toward ending abuses, these matters will be raised in Sydney. If Australia can invite business representatives and security analysts from ASEAN countries, it should have no difficulty inviting civil society groups from the region.

“It would be a big mistake for Australia to gloss over human rights issues because of fears it could push countries closer to China,” Pearson said. “A race to the bottom on human rights with China would be a terrible outcome not only for people in ASEAN countries, but for Australia as well.”

Nearly all ASEAN leaders invited to the summit preside over governments that deny basic liberties and fundamental freedoms to their citizens. A lack of accountability for grave abuses committed by state security forces is the norm throughout ASEAN. The security forces of Myanmar and the Philippines are implicated in ongoing crimes against humanity, and their governments have shown no signs of respecting calls from the United Nations to end the atrocities and hold those responsible to account.

Prime Minister Hun Sen has ruled Cambodia for more than 30 years using violence, intimidation, and politically motivated arrests and prosecutions against all perceived opponents, while allowing high-level corruption and cronyism to flourish. The Cambodian government has banned the political opposition and jailed its leader. Hun Sen recently threatened potential protesters who burn effigies of him in Australia, saying, “I will follow you all the way to your doorstep and beat you right there.… I can use violence against you.”

Thailand is run by a military junta that has curtailed basic rights to expression and association and repeatedly delayed restoring democratic civilian rule. Vietnam and Laos are one-party states that maintain a chokehold on fundamental rights and freedoms. Malaysia and Singapore severely restrict rights to free expression and peaceful assembly.

In addition to addressing Australia’s domestic human rights concerns, Turnbull should speak publicly about the serious human rights problems throughout ASEAN, offer assistance in genuine reform efforts, and press ASEAN leaders to work directly with civil society groups and the general public to build rights-respecting democracies.

“Shutting one’s eyes and hoping that closer trade and security ties will somehow magically transform abusive governments into rights-respecting ones doesn’t work,” Pearson said. “The ASEAN summit shouldn’t just be an opportunity to dance with dictators, but a chance to publicly press them over horrific human rights abuses across the region.”