I will follow you all the way to your doorstep and beat you right there.… I can use violence against you.

–Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen publicly threatening violence against any protesters in Australia who burn effigies of him, Phnom Penh, February 21, 2018

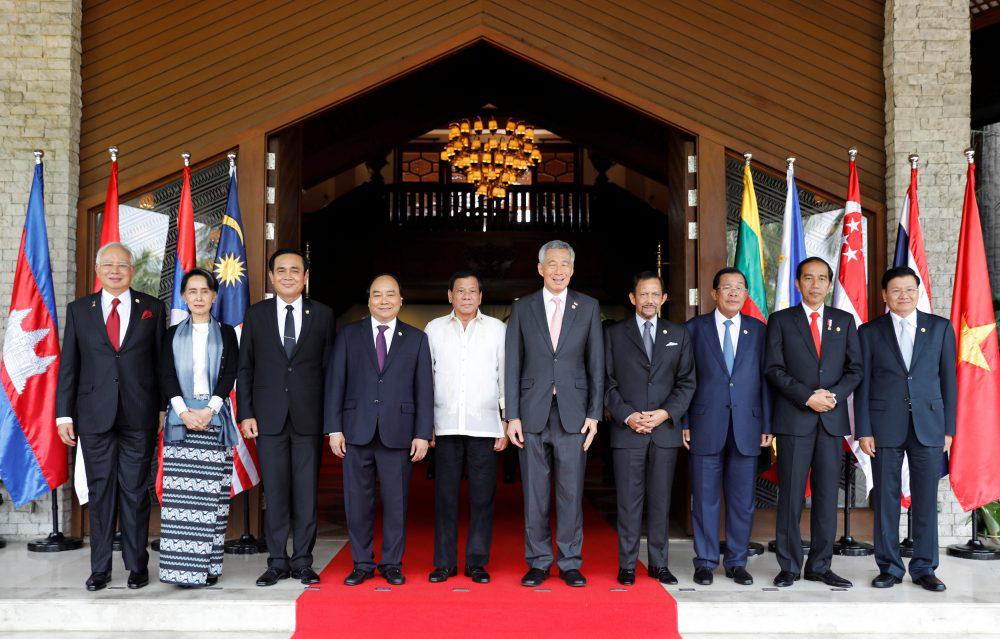

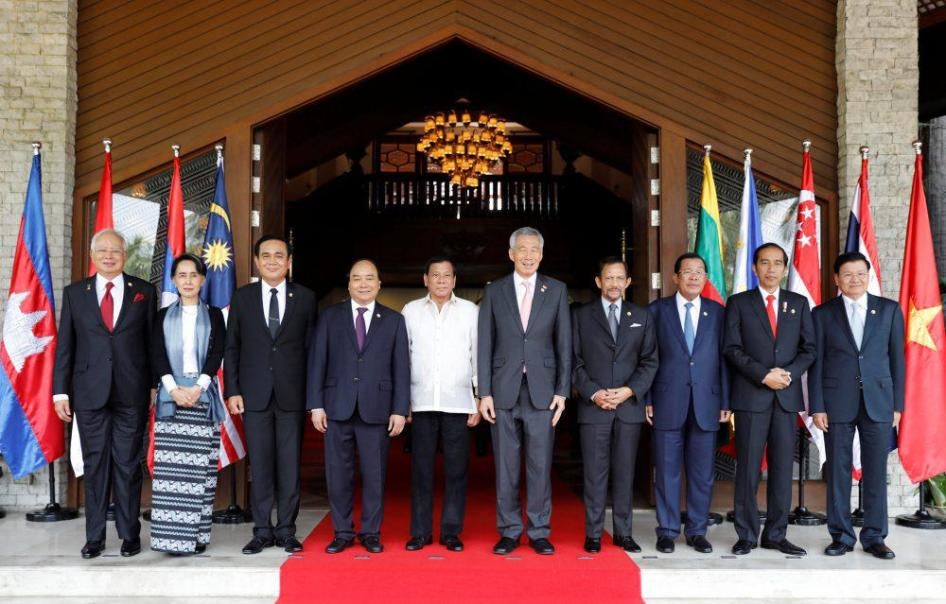

On March 17-18, 2018, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull will host government leaders from the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in Sydney at the ASEAN-Australia Special Summit. The summit will be preceded by a business summit and a counterterrorism meeting to “strengthen our joint contribution to regional security and prosperity, including by addressing shared security challenges and securing greater opportunities.”

For decades, the Australian government has viewed ASEAN as an important economic, security, and political partner, and has forged closer ties with ASEAN countries as they have undergone major economic and political changes. Australia’s Foreign Policy White Paper, released in November 2017, underscores the importance of Australia’s relations with its ASEAN neighbors, saying: “Australia places high priority on our bilateral relationships in Southeast Asia and on our support for ASEAN. The Government is enhancing engagement with the region to support an increasingly prosperous, outwardly-focused, stable and resilient Southeast Asia.”

As global power dynamics shift, United States influence in the region is declining while the political, economic, and military clout of a more assertive China is increasing. In this strategic context, Australia has decided to pursue closer ties with ASEAN countries.

Some ASEAN countries have enjoyed significant economic growth in recent years, but as the chapters below show, many have increasingly serious human rights problems. At a high-level summit of this kind, it would be a major setback for citizens of ASEAN countries for the Australian government to gloss over human rights issues in the hopes of winning over the region’s leaders away from China. Instead, Australia should put its values as a rights-respecting democracy at the center of its relations with ASEAN. Rather than just focusing on good relations with ASEAN leaders, it can do something very different than China: focus on good relations with and the needs of the people of ASEAN, especially in the face of China’s threat to human rights in the region.

Almost all ASEAN leaders invited to Sydney preside over governments that deny basic liberties and fundamental freedoms to their citizens. Many of these governments routinely commit serious human rights violations, crack down on civil society organizations and the media, or undermine democratic institutions by allowing corruption to flourish. A lack of accountability for grave abuses committed by state security forces is the norm throughout ASEAN. The security forces of the Philippines and Myanmar are implicated in alleged crimes against humanity, and their governments have shown no signs of respecting calls from the United Nations to end the atrocities and hold those responsible to account. The Cambodian government has banned the political opposition and jailed its leader. Thailand is run by a military junta that has curtailed basic rights to expression and association and repeatedly delayed restoring democratic civilian rule. Vietnam and Laos are one-party states that maintain a chokehold on fundamental rights and freedoms. Malaysia and Singapore severely restrict rights to free expression and peaceful assembly.

Embracing Abusive ASEAN Leaders

Since August 2017, Myanmar’s military has conducted a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Rohingya Muslims in northern Rakhine State. Security forces have committed massacres, gang rapes, looting, and mass burnings of homes and property, causing the flight of more than 688,000 refugees to Bangladesh. Human Rights Watch has determined that these atrocities amount to crimes against humanity. Myanmar’s de facto leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, has dismissed the allegations, claiming international media have created “a huge iceberg of misinformation.” Her office has accused the Rohingya of setting fire to their own homes and has called allegations of rape “fake news.” Her government has denied visas to a UN-mandated Fact-Finding Mission as well as the UN special rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar, Yanghee Lee.

Since taking office in June 2016, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has presided over a murderous “war on drugs,” a campaign targeting alleged drug dealers and users, whose victims are predominantly the urban poor, including children. Duterte has used criticism of his anti-drug campaign to threaten human rights activists, lawyers, and political opponents. The government has detained for more than a year an important critic of the “drug war,” Senator Leila de Lima, on spurious and politically motivated charges. On March 5, 2018, Duterte announced that he would not attend the ASEAN-Australia summit, but will be represented by Foreign Minister Alan Peter Cayetano.

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen has been in power for more than 30 years, making him the longest-serving head of government in Asia and one of the longest-serving government leaders in the world. In the past year, he has banned the main opposition party, forced the closure of independent media, and cracked down on human rights and other civil society groups. Hun Sen is implicated in possible crimes against humanity committed in the mid-1970s when he was a commander in the Khmer Rouge. He has threatened violence against any protesters in Australia who burn effigies of him.

Thai Prime Minister Gen. Prayut Chan-ocha led the May 2014 military coup that ousted Thailand’s democratically elected government. Prime Minister Prayut’s promises to hold an election to restore civilian democratic rule have been broken repeatedly, with proposed timelines passing without progress. The National Council for Peace and Order junta wields unchecked and abusive powers with total impunity, having prosecuted critics and dissenters, banned peaceful protests, and censored the media. More than 1,800 civilians await trial in military courts. Lese majeste (insulting the monarchy), sedition, and other charges are routinely used to suppress free speech and threaten dissidents. The military and government agencies have frequently retaliated against individuals who report allegations of human rights abuses by bringing criminal defamation charges and seeking prosecution for alleged crimes using the internet.

Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc of Vietnam and President Bounnhang Vorachith of Laos each preside over one-party authoritarian states that deny basic freedoms and use censorship, arbitrary detention, and torture to maintain their respective party’s hold on power. For more than 40 years the communist party in each country has been in power without progress toward pluralism or genuine elections. In the past 18 months, Vietnamese authorities renewed a crackdown against rights activists, arresting dozens and sentencing many to long prison terms.

ASEAN as an institution remains hostile to the promotion of human rights. Under pressure from an increasingly vocal public, in 2007 ASEAN member countries adopted a charter that mentioned human rights principles. But these provisions were heavily outweighed by language emphasizing the importance of “non-interference in the internal affairs” of ASEAN members. In 2009, ASEAN inaugurated an Intergovernmental Human Rights Commission, but it has no real powers: each government appoints its representative to the commission, which works through consensus, a procedural arrangement that effectively prevents reporting on a human rights issue in any one country, since that country would object. The ASEAN Human Rights Declaration, adopted in 2012 without civil society participation, undermines, rather than affirms, international human rights law and standards. It remains a declaration of government powers disguised as a declaration of human rights.

Promoting Rights Advances Australia’s Interests

Australia’s 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper notes that an international rules-based order grounded in human rights is in Australia’s interests:

Australia’s national interests are best advanced by an evolution of the international system that is anchored in international law, support for the rights and freedoms in United Nations declarations, and the principles of good governance, transparency and accountability.… Australia is pragmatic. We do not seek to impose values on others. We are however a determined advocate of liberal institutions, universal values and human rights. The Government believes that our support internationally for these values also serves to advance our national interests. Societies that observe these values will be fairer and more stable. Their economies will benefit as individual creativity is encouraged and innovation rewarded.

Despite this acknowledgment, the Australian government frequently sidelines human rights at summits and other meetings with world leaders. The government rarely raises human rights issues publicly, ostensibly because it does not want to be seen “lecturing” other countries. This may be a legitimate concern, but it is often a convenient excuse for silence and inaction while tacitly accepting ASEAN’s anachronistic insistence on “non-interference in the internal affairs” of other countries. This notion is contrary to international human rights law, whose universality of application places demands on all UN member countries to promote human rights. Australia has also undermined its global standing by being reluctant to raise issues publicly due to shortcomings in its own human rights record, especially regarding treatment of refugees.

China’s growing influence in the region is increasingly used by Australian officials as an excuse not to raise human rights matters publicly. The assumption is that human rights criticism will somehow push these governments ever deeper into China’s fold. This simplistic approach overlooks the diversity of ASEAN countries – each of these countries has its own reasons for a strong or weak relationship with China that includes trade, security, territorial disputes, history, and culture, which human rights only partially impinges upon.

Robust engagement on democracy, governance, and human rights is crucial for the people of ASEAN and the development of ASEAN countries. For example, the proliferation of extrajudicial killings in the Philippines’ “war on drugs” can be attributed in part to the weakness of the country’s democratic institutions, which would benefit from international support. But Australia’s quiet diplomacy sends a message to the people of the Philippines and other ASEAN countries that Australia’s government does not consider upholding their rights a priority.

As the oldest democracy in the region, with robust public institutions, a free media, and an adherence to the rule of law, Australia has much to share with ASEAN governments. In the past, Australia has modestly but effectively led regional coalitions, including leadership on the Paris Peace Accords in Cambodia in the 1990s and on Timor-Leste in 1999. Australia should also not shy away from its own human rights problems and failures, particularly on refugee protection, an issue that is dealt with poorly across the entire ASEAN region.

ASEAN leaders presiding over human rights abuses are under no illusions about their own rights records. They understand that democratic governments will challenge them, and they are awarded an unexpected bonus when countries such as Australia give them a free pass.

The Way Forward

If the ASEAN-Australia summit lacks a strong emphasis on rights, Australia will be sending the message that serious abuses by ASEAN leaders against their citizens will not have a harmful impact on their relationship with Australia.

A better approach would be for Australia to link trade, security, and diplomatic rewards more explicitly to concrete improvements on human rights, for instance, by clearly stating what the costs are for governments that do not implement reforms. In practice, this would mean informing ASEAN governments that closer security and trade engagement will come when political prisoners are released, serious human rights abuses are investigated, and abusive laws are reformed. More specifically, Australia should tell Myanmar that it will impose military sanctions if the government does not end the atrocities against the Rohingya and grant access to the UN-mandated international Fact-Finding Mission. And Australia should indefinitely suspend military exercises with Thailand and Cambodia, which are effectively political endorsements of Prayut’s and Hun Sen’s abusive governments.

One simple and principled step would be for Australia to invite ASEAN-based civil society organizations to participate in ASEAN-related summits. Relegating human rights and civil society to the margins, as sideline issues, is a morally hollow diplomatic exercise. Just as Australia is involving business leaders and security analysts, it should make a concerted effort to intensify engagement with civil society organizations in ASEAN countries.

Australia should demonstrate that it supports the strengthening of institutions that safeguard basic rights, such as independent courts and national human rights bodies, as well as civil society groups that promote the human rights standards and values those institutions are meant to uphold.

The best way for Prime Minister Turnbull to send that message would be to speak publicly about the very serious human rights problems throughout ASEAN, offer assistance in genuine reform efforts, and press ASEAN leaders to work directly with civil society groups and the general public to build rights-respecting democracies.