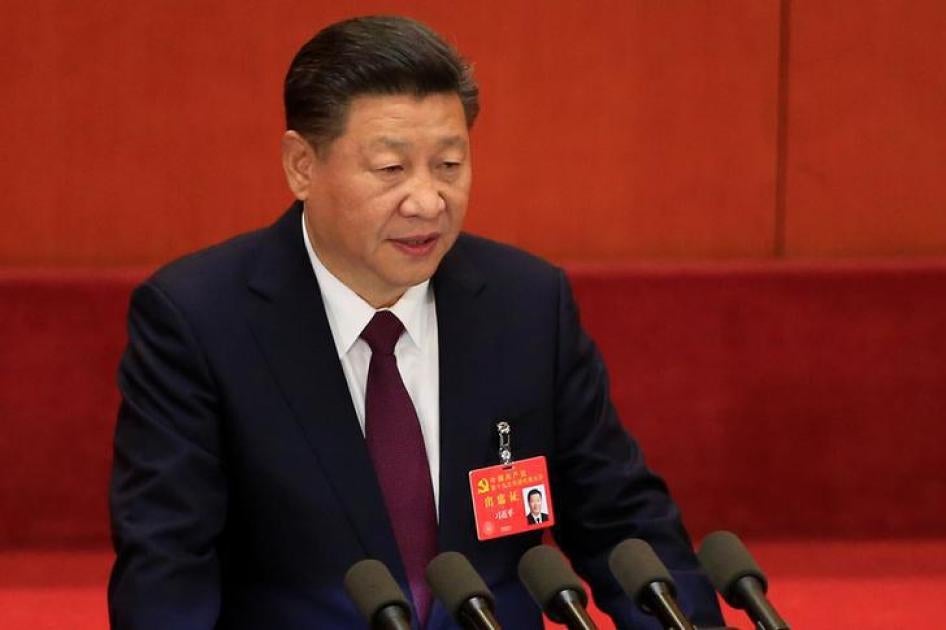

The Chinese Communist Party’s proposal to erase from China’s Constitution term limits for presidents is not a surprise. Current President Xi Jinping, in power since 2013, effectively declined to anoint a successor as he began his second term, and has worked assiduously to consolidate power, indicating his intent to remain in power for the foreseeable future.

The consequences of this stroke-of-a-pen change are potentially devastating for human rights in China, with significant repercussions abroad.

Xi has proven especially hostile to independent civil society. Among his earliest targets: anti-corruption campaigners like the New Citizens Movement. Given Xi’s claim to prioritizing an end to graft, this move was ironic, but it made clear that independent voices would not be tolerated. Since Xi took power five years ago, Chinese authorities have aggressively and assiduously silenced human rights lawyers, women’s rights activists, labor rights activists, legal reformers, language rights advocates, and all manner of peaceful critics of the government. Many have been forcibly disappeared or arbitrarily detained. Beyond that, the state-controlled media have steadily smeared their work, trying to deter future generations of whistleblowers and others who seek to challenge state authorities.

The late Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo once described the Internet as “god’s gift to China”—a tool that could allow people across the country to communicate with some degree of privacy and anonymity. But Xi’s government has also further tightened Internet control and imposed extraordinary mass surveillance systems across the country: second generation IDs, compulsory biodata gathering, facial and voice recognition, and big data systems known as “Police Clouds,” all used to integrate information about people to predict supposed threats to the government’s stability. It is increasingly difficult to perform mundane tasks anonymously, from buying a train ticket to getting a broadband connection, let alone engaging in activity critical of the government.

Another great hope of the 1990s and 2000s: modest legal reform that allowed some room for checks on state power. Again, Xi had other plans: a slew of laws giving the state vague but vast authority, while also strengthening a powerful and unaccountable Party body, the Supervision Commission. That body is now being absorbed into the government, but will sit outside the judicial system. At the same time, there have been no significant advances made on critical legal reforms, such as reducing torture.

These developments obviously have terrible consequences inside China—no effective checks on extraordinary power, leaving more people vulnerable to abuses.

But Xi has demonstrated that his aspirations aren’t limited by China’s borders: he has sought to remake key international institutions, such as United Nations human rights bodies, or simply make institutions do China’s bidding even if contrary to their mandate; for instance, China has used the international law enforcement agency Interpol to harass Chinese dissidents living abroad. Beijing is taking its much-vaunted—yet often deeply abusive—approach to economic development global through initiatives like “One Belt, One Road”; few countries lining up to join appear concerned that the projects lack any community input.

So the stakes couldn’t be higher. Governments concerned by the inroads that a permanent Xi presidency will make on human rights globally need to develop a plan of action in response: insist on established international human rights standards on global threats by China on issues ranging from academic freedom to economic development, and redouble their support to the promotion of human rights inside China. The clock has started.