(Sydney)- People with disabilities in prisons across Australia are at serious risk of sexual and physical violence, and are disproportionately held in solitary confinement for 22 hours a day, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

The 93-page report, “I Needed Help, Instead I Was Punished: Abuse and Neglect of Prisoners with Disabilities in Australia,” examines how prisoners with disabilities, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners, are at serious risk of bullying, harassment, violence, and abuse from fellow prisoners and staff. Prisoners with psychosocial disabilities – mental health conditions – or cognitive disabilities in particular can spend days, weeks, months, and sometimes even years locked up alone in detention or safety units.

State and federal governments should end the use of solitary confinement for prisoners with disabilities, ensure that appropriate services are available to meet their needs, and more effectively screen prisoners for disabilities as they enter prison.

“Being locked up in prison in Australia can be extraordinarily stressful for anyone, but is particularly traumatic for prisoners with disabilities,” said Kriti Sharma, disability rights researcher at Human Rights Watch and author of the report. “The services to support a prisoner with a disability just aren’t there. And worse, having a disability puts you at high risk of violence and abuse.”

Human Rights Watch investigated 14 adult prisons across Western Australia and Queensland and interviewed 275 people, including 136 current or recently released prisoners with disabilities, as well as prison staff, health and mental health professionals, lawyers, academics, activists, family members or guardians, and government officials.

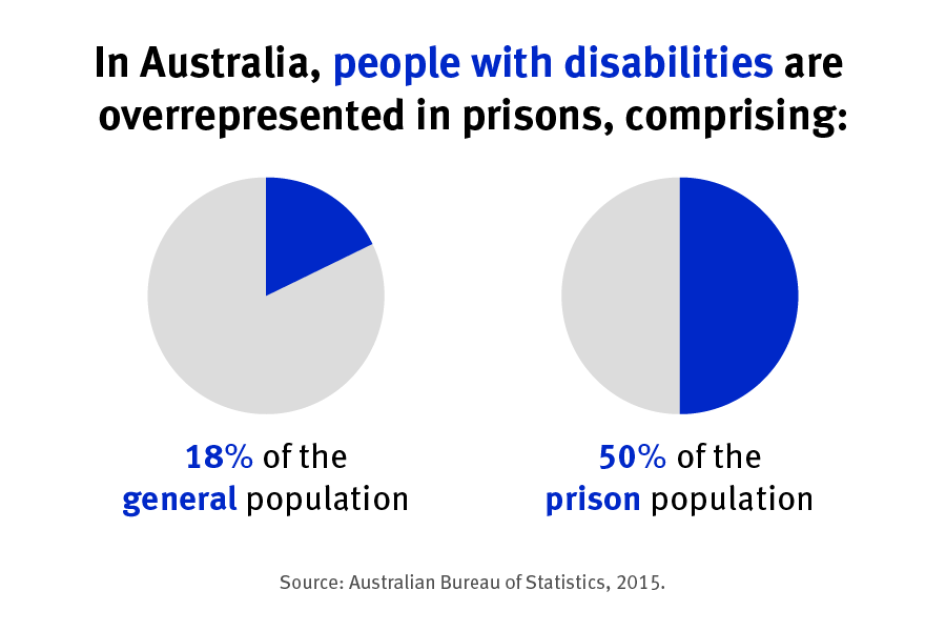

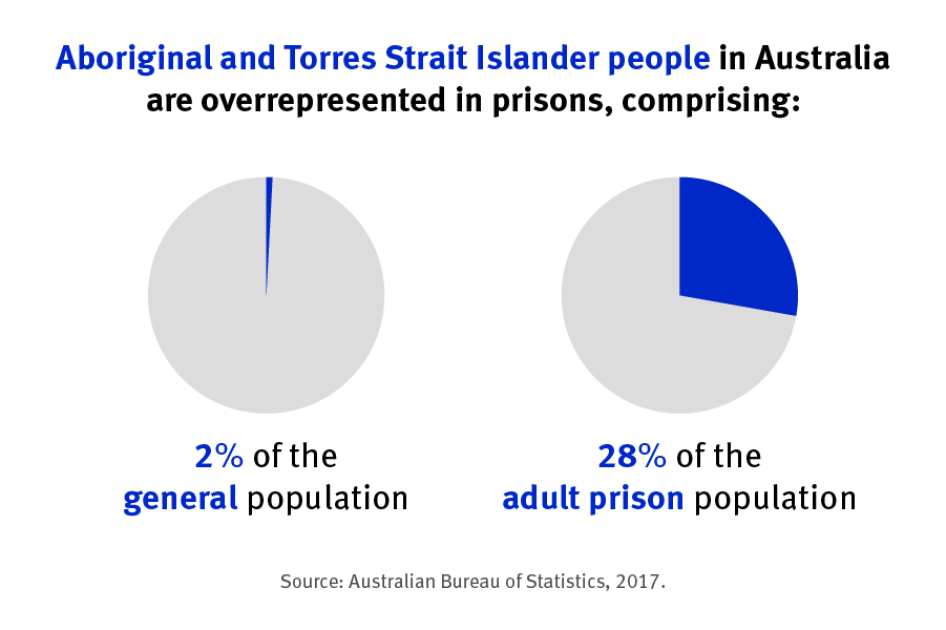

People with disabilities, particularly psychosocial or cognitive disabilities, are dramatically overrepresented in the criminal justice system in Australia – 18 percent of the country’s population, but almost 50 percent of people entering prison. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people comprise 28 percent of Australia’s full-time adult prison population, but just 2 percent of the national population. Within this group, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disabilities are even more likely to end up behind bars.

However, prisons fail to adequately identify people with disabilities and are ill-equipped to meet their needs, often lacking the most basic services.

In 9 out of 14 prisons, prisoners with physical disabilities had to either wait for access to a bathroom, or else shower, urinate, or defecate in humiliating conditions because bathrooms were not accessible. “Toilets are not accessible,” one prisoner said. “I can’t get my chair in. I have to pee in a bottle.” Another said: “I have to wear a nappy every day. I don’t feel like a man; I feel like my dignity is taken away.”

The vast majority of Western Australian and Queensland prisons are overcrowded. In nine prisons, people were often forced to “double-up,” with two and sometimes three people in a cell built for one. Sharing cells can also place prisoners with disabilities at heightened danger of verbal, physical, or sexual violence.

Among those interviewed, 41 people said they had suffered physical violence, and another 32 sexual violence by fellow prisoners or staff. Due to stigma and fear of reprisals, sexual violence is hidden and hard to document, but ever-present in both male and female prisons.

Some prisoners with disabilities with high support needs have “prison-carers” – other prisoners whom prison authorities pay to look after them. In one prison, staff told Human Rights Watch that six out of eight carers were convicted sex offenders and one of them regularly raped the prisoner with a disability in his charge.

In 11 out of 14 prisons, Human Rights Watch found evidence of racism toward Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners. One such prisoner with a psychosocial disability said: “Officers call me ‘black cunt’ heaps of times, it’s normal.”

Prisoners in solitary confinement typically spend 22 hours or more a day locked in small cells, sealed with solid doors, and even contact with staff may be wordless.

Nearly all solitary confinement units Human Rights Watch visited were full and most prisoners with disabilities interviewed had spent time in one. While solitary confinement can be psychologically damaging to any prisoner, its effects can be particularly detrimental for someone with a psychosocial or cognitive disability.

Human Rights Watch found that some prisoners can spend years in prolonged solitary confinement. One man with a psychosocial disability has spent more than 19 years in solitary confinement in a maximum security unit.

Under international standards, the “confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact” amounts to solitary confinement. According to the United Nations special rapporteur on torture, the imposition of solitary confinement “on persons with mental disabilities is cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.”

“Hauling people into the detention unit or safety unit has become common practice for prisoners with mental health conditions,” Sharma said. “Without proper training and alternatives, staff often feel they have no option but to lock them up in solitary confinement.”

State and Territory governments should conduct regular and independent monitoring of prisons to investigate conditions of confinement for prisoners with disabilities, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners, and ensure they do not face abuse, Human Rights Watch said. Queensland, South Australia, Victoria, and the Northern Territory should create an office of the inspector of custodial services that is independent, has adequate resources, and reports directly to parliament.

Prisons should immediately put in place effective systems to screen prisoners with disabilities when they enter prison and provide adequate access to support and mental health services. They should ensure that all prison staff receive regular, gender- and culturally sensitive training on interacting with people with disabilities.

Most importantly, State and Territory government should end solitary confinement for prisoners with disabilities.

“Australian officials should immediately set up inquiries into the use of solitary confinement of prisoners with disabilities, with a view to ending this dehumanizing practice,” Sharma said.

Selected Accounts:

The staff terrorize people in the DU [detention unit]. ‘Heel, dog, heel,’ they said to me…. I was sobbing, they didn’t respond. They opened up the grate [in the cell door] and laughed at me. I swallowed batteries in front of them. [One officer] spat in my face. He said I will punch your teeth all over the cell. Seven other officers were there. They said I was being disruptive. I cut my wrists open. They did nothing, just sat on the bed. [Later] they took me to hospital. I fought with them, I didn’t want it [to go]. I was handcuffed and my feet were shackled. I was in extraordinary pain. I started playing up…. I needed to talk to someone but they ignored me.

– Male prisoner with a psychosocial disability (name and details withheld by Human Rights Watch), Western Australia, 2016

Four officers tackled me. I had played up the day before so they were trying to teach me a lesson. The senior officer stood on my jaw while the other hit my head in and restrained me. They said, ‘You don’t run this prison little cunt, we do,’ and they cut my clothes off. They left me naked on the floor of the exercise yard for a couple of hours before giving me fresh clothes. They probably did it to humiliate me. Officers call me ‘black cunt’ heaps of times, it’s normal.

– Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male prisoner with a psychosocial disability (name and details withheld by Human Rights Watch), Queensland, 2017

I was sexually assaulted [by other prisoners]…. I know at least one of them raped me, but I kind of blacked out. I was bleeding, I still bleed sometimes. I reported it the same day to two of the supers [superintendents], I filled out the medical request form. They told me if I report it, I would go to the DU [detention unit] for six months. So I ripped up the form in front of them. Then when I went back to the unit, I got bashed up by some of the guys, not the ones who assaulted me…. They beat me up, stomped on me. Called me a dog [traitor].

– Male prisoner with a cognitive disability (name and details withheld by Human Rights Watch), Queensland, 2017

They’d [Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners] rather sit back and be sick rather than go see a nurse because the nurse would say ‘Go away, you’re exaggerating.’ ….Racism is alive and well… It manifests itself in stereotyping: aboriginal prisoners are all drug addicts, all involved in domestic violence, all are drug-seeking or untruthful. […] If they question the nurse saying they had an allergic reaction, she will say: ‘You fucking black cunt, you don’t know what you’re talking about. I’m the nurse here. Sit down, shut up, and take your meds.’ A lot of the nurses are very harsh with their comments, swearing, belittling them.

– An Aboriginal cultural liaison officer, in charge of facilitating communication and engagement between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners and prison staff (name and details withheld by Human Rights Watch)

I haven’t seen anyone with an intellectual disability who hasn’t gotten worse in prison. They are often punished [by staff] when struggling to communicate or seeking help. The staff don’t get that people with intellectual disabilities don’t understand what’s happening. Staff take things personally and then act out in anger against the prisoner.

– Psychiatrist who has worked for years in a prison (name and details withheld by Human Rights Watch)

In one case, a prisoner was in solitary confinement for 28 days. After a week, when she was finally granted access to daily exercise, she was placed in a restraint device – a body belt to which a prisoner’s handcuffs are attached – that restricted her movement. During exercise time, correctional officers mocked her, whistled at her as if she were a dog, and told her to crawl on her hands and knees.

– Prisoner’s lawyer (name and details withheld upon request)