Summary

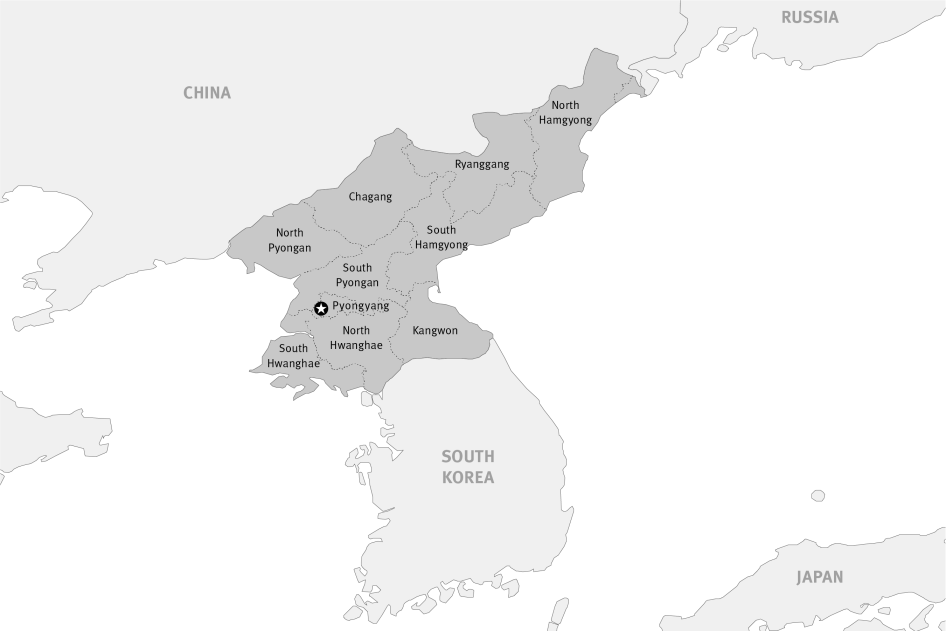

In late 2014, police officers entered the home of Lim Ok Kyung, a smuggler in her forties from North Korea’s South Hwanghae province. The police were looking for, and found, home appliances smuggled from China. Lim Ok Kyung was detained at a detention and interrogation facility (kuryujang) run by the police near the border. Her husband, a mid-level party member, had good connections, so she was released after 10 days. Yet that did not prevent the investigator or police guards from beating her. Lim Ok Kyung described her experience to Human Rights Watch:

The investigator didn’t hit me at the waiting cell (daegisil). But they hit me during questioning.… First, they said to write everything, everything from the moment of my birth until the present. I had to write my whole story

for hours.

The next day the preliminary examination officer came in, said what I wrote was a lie, and asked me to write it again.... When things didn’t match, he slapped me in the face.... Beatings were hardest the first day… [At the individual cell,] some guards who passed by would hit me with their hands or kick me with their boots.…. For five days, they forced me to stay standing and didn’t let me sleep…. When a police guard I knew came in, they’d give me candy saying I was suffering, they’d let me sit and rest. But when the guards I didn’t know were in charge of watching me… they wouldn’t let me sleep.

Yoon Young Cheol, at the time a government worker in his thirties, also experienced the arbitrariness of the North Korean legal system. On a winter night in 2011, five men dressed as police officers entered his home and took him to the office of the secret police (bowibu) in the city bordering China where he lived. Yoon Young Cheol was detained and, before he was even questioned, severely beaten. It was only the next day that he found out that somebody had accused him of being a spy. He told Human Rights Watch:

They put me in a waiting cell. It was small and I was alone. They searched my body. Afterwards, the head of the city’s secret police department, the party’s political affairs head, and the investigator came in. It was very serious, but I didn’t know why. They just beat me up for 30 minutes, they kicked me with their boots, and punched me with their fists, everywhere on my body.…

The next day they moved me to the next room, which was a detention and interrogation facility cell, and my preliminary examination started. But the questioning didn’t really have any protocols or procedures. They just beat me…. The preliminary examiner hit me violently first… I asked, ‘Why? Why? Why?’ but I didn’t get an answer…. As the questioning went on, I found out that I had been reported as a spy. Violent beatings and hitting were constant in the beginning of [the preliminary examination] questioning for one month. They kicked me with their boots, punched me with their fists or hit me with a thick stick, all over my body. After [when they had most of my confession ready], they were gentler.

Six months later, Yoon Young Cheol says the secret police concluded that he was not a spy and passed him over to the police. The police then investigated him for two more months on allegations of smuggling forbidden products such as herbal medicines, copper, or gold. After a summary trial, Yoon Young Cheol was sentenced to unpaid hard labor for five years. He explained that anybody making noteworthy amounts of money in North Korea can easily be found guilty of crimes, as most profit-making activities can be considered illegal.

The experiences of Lim Ok Kyung and Yoon Young Cheol are hardly unique. As is widely known, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, North Korea) is one of the most repressive countries in the world. It is a totalitarian, militaristic, nationalistic, and highly corrupt state. All basic civil, political, social and economic rights are severely restricted under the rule of Kim Jong Un and his family’s political dynasty. The ruling party and government use the constitution, laws and regulations, control of the legal and justice system, and other methods to legitimize Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK) and government directives.

In 2014, a United Nations Commission of Inquiry (COI) on human rights in the DPRK established that systematic, widespread, and gross human rights violations committed by the North Korean government constituted crimes against humanity. These crimes include murder, extermination, imprisonment, enslavement, persecution, as well as enforced disappearances of and sexual violence perpetrated against North Koreans in prison and in detention after forced repatriation. The COI also documented torture, humiliation, and intimidation, as well as deliberate starvation, during investigation and questioning in pretrial detention and interrogation facilities as an established feature of the process in efforts to subdue detainees and extract confessions, particularly from people forcibly returned from China to North Korea.

This report—based largely on research and interviews conducted with 22 North Koreans detained in detention and interrogation facilities after 2011 (when Kim Jong Un came to power) and eight former North Korean officials who fled the country—provides new information on North Korea’s opaque pretrial detention and investigation system. It describes the criminal investigation process; North Korea’s weak legal and institutional framework; the dependence of law enforcement and the judiciary on the ruling WPK; the apparent presumption of guilt; bribery and corruption; and inhumane conditions and mistreatment of those in detention and interrogation facilities (kuryujang) that often amounts to torture.

Because North Korea is a “closed” country, not much is known about the legal processes in its pretrial detention system, but the experiences of those interviewed and the other evidence detailed below, show that torture, humiliation, coerced confessions, hunger, unhygienic conditions, and the necessity of connections and bribes to avoid the worst treatment appear to be fundamental characteristics.

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that once a detainee faces an official investigation (susa), there is little chance of avoiding short-term sentences of unpaid hard labor at detention centers (rodong danryeondae, literally “labor training centers”) or a long-term or life sentence of hard labor at an ordinary crimes prison camp (rodong kyohwaso, literally “reform through labor centers”).

All former detainees told Human Rights Watch that they were forced to sit still on the floor, kneeling or with their legs crossed, fists or hands on top of their laps, heads down, with their eyesight directed to the floor for 7-8 hours or, in some cases, 13-16 hours a day. If a detainee moves, guards punish the detainee or order collective punishment for all detainees. Abuse, torture, and punishment, including for failing to remain immobilized when ordered, appear to be more acute when interrogators are attempting to obtain confessions. Because detainees are treated as though they are inferior human beings, unworthy of direct eye contact with law enforcement officers, they are referred to by a number instead of their names. Some female detainees reported sexual harassment and assault, including rape.

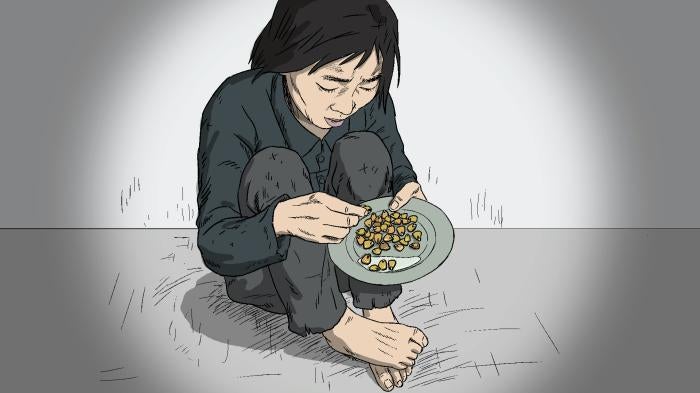

Interviewees described unhealthy and unhygienic detention conditions: very little food with low nutritious value (80-200 grams of boiled corn and soup with wild greens or radishes three times a day), overcrowded cells with no space to sleep, little opportunity to bathe, and a lack of blankets, clothes, soap, and menstrual hygiene supplies. At times, guards or interrogators allowed family members or friends to bring food, clothes, soap, blankets, or money after questioning was over. Bribes and connections could persuade law enforcement officials to ignore or reduce the charges, improve conditions and treatment while in detention, or even have the case dismissed entirely.

North Korean laws are generally vaguely phrased, and while they make passing reference to certain rights, they do not include important safeguards for defendant and detainee rights set forth in international standards. They contain important omissions and lack clear definitions, leaving them open to interpretation and maximizing the discretion of government officials to decide how, or indeed whether, to execute the law.

For instance, North Korean law recognizes citizens’ right to a fair trial, and testimonies obtained under duress or inducement and confessions that are the sole evidence of proof are not supposed to be used in court. However, there is no prohibition against using evidence gathered illegally, and no safeguard for the presumption of innocence, the right against self-incrimination, or the right to remain silent. The DPRK Criminal Code and the DPRK Criminal Procedure Code do not contain any provisions allowing for judicial review of detention at the investigation or preliminary examination stages. And, because the ruling party controls all institutions in North Korea, the Party Security Committee (dang anjeon wiwonhoi) has to give approval for law enforcement agents to finalize a decision to pursue criminal charges.

Korean Language Glossary

Boanseong: police, Ministry of People’s Security, full name inmin boanseong, renamed in May 2020 as the Ministry of Social Security, in Korean sahoe anjeonseong, formerly also called boanbu

Boanbu: police, currently called sahoe anjeonseong

Boanseong danryeondae: short-term (between six months and one year) hard labor detention center run by the police

Bowi saryeongbu: Military Security Command

Bowibu: secret police, State Security Department, full name kugga anjeon bowibu, currently called bowiseong

Bowiseong: secret police, Ministry of State Security, full name kugga bowiseong, formerly called bowibu

Chepo: arrest with a warrant

Daegisil: holding cell, literally “waiting room”

Dang anjeon wiwonhoi: Party Security Committee

Dansok: Regulation, control, crackdown

Do: province

Gugumsil: jail, holding cell in small or remote security and law enforcement agency offices, literally “detention room”

Gun/Guyeok: district

Ice: methamphetamines, also called bingdu

Inmin boanseong: Ministry of People’s Security, police, often referred to as boanseong

Inminban: neighborhood watch system, literally “people’s unit/group”

Jangmadang: private markets

Jeongsang: severity, circumstances (of a crime)

Jipkyulso: temporary holding facility, literally “gathering place”

Kimchi: vegetables, usually cabbage, fermented with salt and other spices

Kiso: prosecution

Komun: torture

Kukga bowiseong: Ministry of State Security, secret police, often called bowiseong, formerly called bowibu

Kuryu: detention without a warrant

Kuryujang: pretrial detention and interrogation facility, literally "place for detention”

Kwanliso: penal hard labor colony for serious political crimes or political prisoners’ camps, literally “control center”

Kyohwaso: long-term (over one year) hard labor ordinary crimes prison camp, also called rodong kyohwaso or re-education camp, literally “reform through labor center”

Mugi rodong kyohwahyeong: unpaid hard labor for life at ordinary crimes prison camps (kyohwaso), literally “life-term of reform through labor criminal penalty”

Naegak: Cabinet

Ri: village

Rodong danryeondae: short-term (less than six months) hard labor detention center, literally “labor training center”

Rodong danryeonghyeong: short-term (between six months and one year) unpaid hard labor sentence, literally “labor training criminal penalty”

Rodong kyohwahyeong: long-term (more than one year) unpaid hard labor sentence at hard labor ordinary crimes prison camps (rodong kyohwaso), literally “reform through labor criminal penalty”

Rodong kyohwaso: long-term (over one year) hard labor ordinary crimes prison camp, sometimes also called re-education camp or kyohwaso, literally “reform through labor center”

Rodong kyoyang cheobun: short-term (between five days and six months) unpaid hard labor administrative penalty, literally “labor awareness penalty”

Sahoe anjeonseong: police, also referred to as anjeonseong, formerly called boanbu or boanseong

Sahoejeok kyoyang cheobun: short-term administrative penalty to be spent self-reflecting on proper citizenship morality, literally “social awareness penalty”

Si: city

Suryong: Supreme Leader

Susa: investigation

Songbun: a socio-political classification system, literally “ingredient, element”

Yesim: preliminary examination

Yesimwon: preliminary examination officer or preliminary examiner

Yugi rodong kyohwahyeong: fixed long-term (between one and 15 years) unpaid hard labor at hard labor ordinary crimes prison camps, literally “limited term of reform through labor criminal penalty”

Acronyms

CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

CRC Convention on the Rights of the Child

CRPD Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

COI Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea

DPRK Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

FIDH International Federation for Human Rights

ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

KINU Korea Institute of National Unification

MPS Ministry of People’s Security

MSC Military Security Command

MSS Ministry of State Security

NKDB Database Center for North Korean Human Rights

OGD Organization Guidance Department

SPA Supreme People’s Assembly

UDHR Universal Declaration of Human Rights

UN United Nations

WPK Workers’ Party of Korea

Key Recommendations

To the North Korean Government

- Undertake legal, constitutional, and institutional reforms to establish an independent and impartial judiciary and introduce genuine checks and balances on the powers of the police, security services, government, the Workers’ Party of Korea, and the Supreme Leader.

- Establish a professional and independent police force and investigative system that meet international standards.

- Reform the legal system to ensure due process and fair trials that meet international standards, including the presumption of innocence during investigations and at trials and access to legal counsel of one’s own choosing throughout the entire legal and judicial process.

- Review the domestic legal framework to ensure that it fully complies with the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders (the “Bangkok Rules”).

- Take immediate steps to improve abysmal conditions of detention and imprisonment and bring them up to basic standards of hygiene, health care, nutrition, clean water, clothing, floor space, light, and heat.

- End endemic torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment in detention and prison, including sexual violence, hard labor, being forced to sit immobilized for long periods, and other mistreatment.

- Allow visits to prisons and other places of detention by the International Committee of the Red Cross and UN human rights monitors, including the UN special rapporteur for North Korea and the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Methodology

North Korea rarely publishes data on any aspect of life in the country. When it does, it is often limited, inconsistent, inaccurate, or otherwise of questionable utility. North Korea strictly limits foreigners’ access to the country and contact between local residents and foreigners. It does not allow independent human rights research of any kind in the country. For these reasons, Human Rights Watch did not conduct any interviews in North Korea for this report.

This report is based on interviews and research conducted by Human Rights Watch staff and a consultant between January 2015 and May 2020. Human Rights Watch interviewed 46 North Koreans outside the country. Among them, 22 (15 women and seven men) had been held in pretrial detention and interrogation facilities (kuryujang) after 2011, when North Korea’s current leader Kim Jong Un came to power.

We interviewed more women because they constitute the vast majority of North Koreans who are able to leave the country since surveillance is less stringent on women than men, and illegal networks are more willing to assist North Korean women as trafficked persons.

We also interviewed eight former government officials who worked at detention and interrogation facilities or had professional connections with them and who still have regular contacts in North Korea. These include three former police officers, a prison guard, an official from the Ministry of State Security (MSS, secret police, kukga bowiseong), a military officer who visited detention and interrogation facilities near the border, and two party officials.

All interviews were conducted in Korean. Interviewees were advised of the purpose of the research and how the information would be used. They were advised of the voluntary nature of the interview and that they could refuse to be interviewed, refuse to answer any question, and terminate the interview at any point. In all cases, interviews were conducted in surroundings chosen to enable interviewees to feel comfortable, relatively private, and secure.

Human Rights Watch did not remunerate any interviewees for doing interviews. Human Rights Watch provided minimum wage compensation to interviewees who had to miss work to make time for the interview. For those living far from the location of the interviews, Human Rights Watch covered transportation costs.

Most interviewees expressed concern about possible repercussions for themselves or their family members in North Korea and asked to remain anonymous. To protect these individuals from possible punishment, all names of former detainees used in this report are pseudonyms. Human Rights Watch also has not included personal details that could help identify victims and witnesses.

North Koreans who flee the country are almost always called “defectors” by North Koreans, South Koreans, foreign experts and observers, researchers, journalists, NGO workers, government officials, and so on. This report, however, refers to them simply as “North Koreans” or as “escapees”: the word “defector” presupposes a political motivation for leaving that may or may not be present. North Koreans leave their country for many reasons, including for economic and medical reasons.

We also conducted additional interviews with experts familiar with issues concerning North Korea’s detention and prison system, activists, legal experts, and academics. We obtained and reviewed relevant documents available in the public domain from UN agencies, local NGOs in South Korea working on North Korea’s detention and prison system, North Korean government agencies, researchers, and international analysts. These documents helped provide important insight into the context of pretrial detention in North Korea.

Unfortunately, many North Korean laws, internal regulations, and decrees that may be relevant to the pretrial detention and criminal procedure process are not publicly available or when accessible, may be outdated. No official information was available about the pretrial detention process for political crimes under the Ministry of State Security, which has its own set of confidential internal guidelines that supersede publicly available laws and procedures.

The relatively small number of interviews conducted for this report limits the ability of Human Rights Watch to reach conclusions about conditions in all detention and interrogation facilities in North Korea. However, the diversity in geographic location and the similarities in conditions and personal experiences of the interviewees suggest the issues identified here are of general concern. Based on our findings and previous documentation, we have every reason to believe mistreatment of detainees, dangerous and unhealthy conditions, presumption of guilt, lack of due process and flawed trials are the norm.

I. North Korea’s Security and Law Enforcement Agencies

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, hereafter North Korea) is perhaps the world’s most restrictive police state. The ruling Worker’s Party of Korea (WPK) oversees a complex and highly developed security system that employs strict surveillance, violence, coercion, fear, and harsh punishment to ensure ideological conformity in order to silence dissent among the country’s 25 million citizens and maintain the power of the country’s leader, Kim Jong Un, and the WPK.[1]

Telephones, computers, and correspondence are monitored, the internet is inaccessible except to a very small number of high-ranking party officials, radios and televisions receive only government-authorized stations, and all media content is heavily censored.[2] From childhood, people’s thoughts are continually monitored and shaped by an all-encompassing indoctrination machine to manufacture absolute obedience to the Supreme Leader (suryong). Informant networks exist in every social, economic, and political group and all North Korean citizens are under constant surveillance by the party through mass associations or the neighborhood watch system (inminban, literally “people’s unit/group”).[3] An elaborate political caste system (songbun) classifies the population into categories based on the regime’s determination of a person’s loyalty and performance and assigns every individual a narrowly prescribed role in society.[4]

The Ministry of State Security (MSS, secret police, or kukga bowiseong) investigates political crimes, which are considered crimes committed by enemies or “counter-revolutionaries” against the people, the party and the government.[5] The MSS has its headquarters in Pyongyang and offices at the provincial (do), city (si) and local (gun/guyeok) levels.[6] It officially works under the State Affairs Commission, but also reports to the Supreme Leader. It reportedly has tens of thousands of employees.[7]

The MSS runs political prisoner camps (kwanliso), as well as temporary holding facilities (jipkyulso) at the provincial level. The MSS also operates some holding cells (gugumsil or daegisil) and a network of detention and interrogation facilities (kuryujang).[8] It also runs a number of secret guarded holding buildings, euphemistically described as “guest houses.”[9] The MSS is the most obscure institution within the North Korean government, as it has its own set of secret, confidential internal regulations and guidelines.[10]

The Ministry of Social Security (police, in Korean sahoe anjeonseong) is responsible for maintaining law and order and social control, investigating ordinary crimes, detaining and interrogating offenders, and imposing penalties for misbehavior deemed not serious enough to prosecute under the criminal law.[11] It is responsible for administering short-term unpaid hard labor detention centers (boanseo danryeondae and rodong danryeondae ) and ordinary prison camps (rodong kyohwaso).[12] The police has its headquarters in Pyongyang and offices at the provincial, city and various local (guyeok/gun/jigu) and village (ri) levels.[13] The police also operates a network of pretrial detention and interrogation facilities (kuryujang) at the national, provincial, city, and local levels.[14]

The Military Security Command (MSC, in Korean bowi saryeongbu) serves as the political police of the Korean People’s Army (KPA) under the Ministry of People’s Armed Forces. It operates under a set of secret, confidential internal regulations.[15] It is in charge of internal security within the army, investigates and conducts surveillance of military organizations and high-ranking military officers, local party organizations, and individual cadres.[16] The MSC reportedly runs pretrial detention and interrogation facilities and short-term forced labor detention centers (rodong danryeondae) adjacent to political prison camps.[17] The MSC’s mandate also extends to providing security for the Supreme Leader during his visits to military units and monitoring military and civilian movements along North Korea’s northern and southern borders.[18]

The MSS, police, and MSC report to the State Affairs Commission. The State Affairs Commission is the supreme policy-oriented leadership body of the state. It is in charge of all important state policies, including defense and the armed forces, ensuring the fulfilment of the orders of the Chairman of the State Affairs Commission, and abrogating decisions and directives of state organs which run counter to the orders of the Chairman of the State Affairs Commission and the decisions and directives of the State Affairs Commission.[19] Kim Jong Un is the head of the State Affairs Commission.[20]

While there is a clear official chain of command within the main security agencies, there is also control and guidance by special bodies in the party, which also have surveilling and investigative roles over senior officials or security agencies. For example, the WPK’s Central Committee’s Organization Guidance Department (OGD) is in charge of implementing the Supreme Leader’s directives. The OGD has oversight and a guiding role over the police, MSS and MSC.[21] The OGD is also in charge of surveillance and inspection, as well as the appointment, of senior party officials.[22]

The Prosecutor’s Office directly investigates crimes related to administrative and economic projects and those involving law enforcement agencies.[23] It is one of the country’s most powerful agencies, with the power to audit other state organs.[24] Its official responsibilities include ensuring the strict observance of state laws by institutions, enterprises, organizations and citizens; ensuring the decisions and directives of state bodies conform with the Constitution, the laws, ordinances and decisions of the Supreme People’s Assembly, the orders of the Chairman of the State Affairs Commission of the DPRK, the decisions and directives of the State Affairs Commission, the decrees, decisions and directives of the Presidium of the Supreme People’s Assembly,[25] and the decisions and directives of the Cabinet; and identifying and instituting legal proceedings against criminals and offenders in order to protect the state power of the DPRK, the socialist system, the property of the state and social, cooperative organizations, personal rights as guaranteed by the Constitution and the people’s lives and property.[26] Some of the prosecutor’s offices have holding cells (gugumsil) or detention and interrogation facilities (kuryujang).[27]

The prosecutor’s office, as all bodies connected to the party, is structured with a central prosecutor’s office, provincial, city, and local (gun) level offices.[28] It also has special prosecutor’s offices, like the military prosecutor’s office, which has jurisdiction over ordinary crimes committed by personnel from the military and the police, the railway prosecutor’s office, in charge of ordinary crimes related to the railway transport sector, and the military logistics prosecutor’s office, in charge of specific crimes related to the military logistics department.[29] The prosecutor’s office is accountable to the Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA), North Korea’s unicameral legislature, or, when it is not in session, its presidium.[30]

Despite the official roles of the various security agencies, in practice their remit has varied over time and in different parts of the country. This has been a function of changing political priorities, available capacity, the relative power of senior officials, and the extent to which a particular agency enjoys the trust of the Supreme Leader. The three main security agencies, the MSS, police and Military Security Command, frequently compete to gain the leadership’s favor by identifying ideological opponents and threats.

II. A Flawed Criminal Procedure Law and System

The criminal justice system in North Korea, like its constitution, laws, other legal instruments, and government bodies, is a byproduct of the government’s efforts to protect the leadership and its political system, and to legitimize ruling party directives. In service of these ends, it also prescribes harsh punishment for non-compliance.[31] The system is grounded in a guiding ideology that gives primacy to the statements and personal directives of the country’s leader; [32] the “Ten Principles of the Establishment of the Monolithic Ideological System” of the WPK;[33] the rules of the party;[34] the Socialist Constitution;[35] and, finally, domestic laws.[36] For example, article 2 of the criminal procedure code requires the state to carefully identify friends and enemies of the state in its struggle against “anti-state and anti-people crimes.”[37] Article 162 of the constitution requires the courts to ensure obedience of state law and “to staunchly combat class enemies.”[38]

North Korea’s legal system is governed by the “law of the socialist society and national sovereignty that perform a function of the proletarian dictatorship.”[39] A Commission of Inquiry (COI) on the situation of human rights in North Korea stated “the law and the justice system serve to legitimize violations, there is a rule by law in the DPRK, but no rule of law, upheld by an independent and impartial judiciary. Even where relevant checks have been incorporated into statutes, these can be disregarded with impunity.”[40]

Criminal Law, Procedure and Punishment

The North Korean system for the investigation, trial and sentencing of crimes is both straightforward and complex. North Korea’s Criminal Code and Criminal Procedure Code are relatively short and, in many respects, similar to other countries. But the laws have many gaps and inconsistencies that make them complicated to understand. The country has an official, law-based judicial system, but it also has a party-based quasi-judicial system that works in parallel and can supersede the official system in an opaque manner. Arbitrariness in the application of the law adds another layer of confusion for North Korean detainees and even law enforcement personnel.

The Criminal Code was adopted in 1990, and last amended in 2015. In 2007, the Addendum of the Criminal Code, a separate law that complements the Criminal Code, was adopted and introduced stronger penalties.[41] Broadly, criminal sanctions are applied for committing “dangerous acts that with intention or negligence infringe in the sovereignty of the state, the socialist system, and law and order.”[42] The main criminal penalties are death; unpaid hard labor for life (mugi rodong kyohwahyeong, in Korean literally “life-term of reform through labor criminal penalty”); a fixed long term (between one to 15 years) of unpaid hard labor (yugi rodong kyohwahyeong, in Korean literally “limited term of reform through labor criminal penalty”); and a short term (between six months and one year) of unpaid hard labor (rodong danryeonhyeong, literally “labor training criminal penalty”).[43]

Minor criminal offenses are dealt with under the Administrative Penalty Law, which was adopted in 2004 and was last amended in 2011. It applies sanctions “to institutions, businesses, organizations and citizens who committed an offense that doesn’t reach the point of requiring a criminal penalty.”[44] Violations of the law are adjudicated by the “Socialist Lawful Lifestyle Guidance Committee” as well as the Cabinet (naegak, the highest administrative and executive body of the government), the Prosecutor’s Office, courts, police, inspection agencies, state-owned enterprises and other institutions. All administrative penalties applied must be reported every quarter to the “Socialist Lawful Lifestyle Guidance Committee.”[45]

The police can also apply the DPRK People’s Security Regulation Law,[46] adopted in 1992 and last amended in 2005, which authorizes the police to detain offenders and impose penalties for violations such as breaking or stealing production materials, making fake reports about government development projects, practicing fortune-telling, using unregistered computers, or copying and distributing “decadent” music, drawings, photos or books.[47] This law also applies to those who “violate the law and order but not to the point of deserving criminal responsibility.”[48]

The DPRK Criminal Procedure Code was adopted in 1950 and last amended in 2012. It sets out the process for detention, arrest, investigation, trial and sentencing under North Korean law.

The Criminal Code and Criminal Procedure Code apply to all security agencies, such as the police or the secret police.[49] Time limitations and procedural steps provided by the law are usually respected for ordinary crimes handled by the police. However, the secret police, or the Military Security Command have a higher status since their main priority is regime protection and their secret internal regulations and guidelines allow them to ignore or override the Criminal Code and Criminal Procedure Code in certain circumstances.[50]

For minor or medium political offenses, the MSS may use the DPRK Criminal Procedure Code to punish crimes.[51] But even then suspects are frequently arrested at night, in the street or at their workplace and brought to a detention and interrogation facility, where they can spend months being interrogated at length by different security agencies.[52] If the MSS determines that the suspect committed a minor political infraction or the case is deemed non-political it usually refers the individual for further interrogation to the police, where an investigation recommences.[53]

North Korean law also contains important omissions. Neither the Criminal Code nor the Criminal Procedure Code contains any provisions allowing for judicial review of detention at the investigation or preliminary examination (yesim) stages. This gives officials wide discretion in the stages after detention or arrest. North Korean laws are also generally vague and do not adhere to international standards. They lack clear definitions, leaving them open to arbitrary interpretation that maximizes the discretion of government officials to decide how or, indeed, whether to follow the law.[54]

North Korean law professes that the state fully guarantees human rights in handling criminal cases.[55] While the term “torture” (komun) is not used in the law, the law forbids the use of force or inducements during evidence gathering.[56] Testimonies obtained under duress or inducement, and confessions that are the sole evidence of guilt, cannot be used in court.[57] Article 166 of the DPRK Criminal Procedure Code prohibits a preliminary examiner from using “forceful methods to make the suspect admit the crime or to make a statement.”[58] Article 37 of the law states that “the statements of the suspect received by means of coercion and inducement shall not be used as evidence. If the testimony of the suspect is the only evidence, it is admitted that the crime could not be proved. Even with the surrender and confession of a suspect, other relevant evidence must be found to be admitted. If it is objectively found that the statements of a suspect who does not acknowledge the crime are false by other evidence, the crime is recognized as proven.”[59]

There is no prohibition against using evidence gathered illegally. The law fails to include the presumption of innocence, the right against self-incrimination, or the right to remain silent.[60] To the contrary, article 283 of the DPRK Criminal Procedure Code requires an accused to “answer questions when asked.”[61] The right to legal counsel is limited as an accused can only retain a lawyer after a preliminary examiner finalizes a decision to pursue criminal liability,[62] and because detainees do not have access to information about lawyers unless they have personal connections. In addition, all lawyers in North Korea lack independence, as they operate under the oversight of party-controlled lawyers’ committees.[63]

Criminal Investigation and Prosecution

The DPRK Criminal Procedure Code outlines the stages of investigation (susa), preliminary examination (yesim), prosecution (kiso), trial, and sentencing for criminal cases. The investigation’s goal is to “uncover the criminal” and hand the suspect over to a preliminary examination procedure.[64] The aim of the preliminary examination (yesim) is “to expose the offender and reveal all details of the criminal case completely and accurately.”[65] The duty of the prosecution is to “conduct a full review of the case records of the finalized preliminary examination and hand over the criminal case to the court if it recognizes that all details of the crime have been completely and accurately revealed during the preliminary examination.”[66] The objective of the first-instance trial is “to confirm crimes and criminals and to analyze them based on the law and make a court ruling.”[67]

Investigation

The investigation (susa) period, which usually lasts a few days, is crucial, as an individual will either be released or sent to the next stage, preliminary examination, which usually results in a trial and conviction and could lead to a heavy sentence. Investigations are usually conducted by investigators from the police or the secret police, the main law enforcement agencies.[68]

Article 135 of the DPRK Criminal Procedure Code allows law enforcement officials 24 hours to officially register an investigation with the Prosecutor’s Office, which can turn down the request if there are no reasonable grounds to start the investigation.[69] During this period, the law enforcement or security official in charge of the investigation can obtain a warrant from a prosecutor allowing the arrest of a suspect for questioning for up to 10 days in a holding or waiting cell (gugumsil or daegisil) or detention and interrogation facility (kuryujang).[70] It is worth noting that none of the former detainees interviewed by Human Rights Watch ever saw a warrant.[71] During this 10-day period the police or other investigator decides whether to release the suspect or send the case to the preliminary examination stage.[72]

The police or investigators are also allowed to detain suspects without prosecutorial approval. In such cases, the investigator must obtain approval from the prosecutor within 48 hours of arrest (chepo, with a warrant) or detention (kyuru, without a warrant). As above, the investigator must release the suspect within 10 days of detention or send the case for preliminary examination.[73] If the investigator cannot obtain the approval of the prosecutor, the investigator needs to prove the crime within 10 days or release the suspect.[74]

A former police officer familiar with pretrial detention procedures told Human Rights Watch that investigators send many people accused of minor crimes to short-term hard labor detention centers, others for short-term administrative penalties to self-reflect on proper social behavior or the improper citizen behavior committed (sahoejeok kyoyang cheobun, literally “social awareness penalty”) and about half for preliminary examination.[75] A former party official with connections within the criminal procedure system estimated that as many as 90 percent of possible cases may be dropped or sent for short-term hard labor, with only 10 percent being sent for preliminary examination, for criminal prosecution and trial.[76] “The police also need to survive, and they need to get bribes to do so,” he said.[77] Indeed, bribery is reportedly rampant. Four former government officials, including two former police officers, told Human Rights Watch that most crimes that could be considered minor would not even lead to an investigation if the offender paid a bribe or had enough connections.[78]

Preliminary Examination

The preliminary examination (yesim) usually takes place while detainees are in custody. The preliminary examination officer may detain or arrest a suspect if the alleged crime is punishable by hard labor for life or long-term or death, or if the suspect interferes with the investigation, does not cooperate with the preliminary examination procedure, or flees preliminary examination or trial.

In cases in which the preliminary examination starts before a suspect is detained, the preliminary examination officer may issue a subpoena to question the suspect. If the suspect is not detained before the preliminary examination is finished and the decision is to charge the suspect, the preliminary examination officer (yesimwon) can request an arrest warrant from prosecutors if the alleged crime is punishable by long-term hard labor, hard labor for life, or death. When the offense is punishable by short-term labor the suspect can only be arrested or detained in (undefined) special circumstances. The law says that female suspects cannot be detained three months before childbirth or within seven months after childbirth, but it is unclear whether this would be the case if a woman committed a serious crime.[79]

While the investigation focuses on identifying the criminal, the preliminary examination is supposed to develop a complete and accurate understanding of the case, including the nature of the crime, the motives and objective, the means and role of the accused, and the results of the crime.[80]

Law enforcement agencies, including the police, the secret police and the prosecutor’s office, have separate departments for investigation and preliminary examinations and the preliminary examination officer is supposed to be from a department separate from the investigation office.[81] The law states that the preliminary examination officer must decide whether or not to start this process within 48 hours after receiving a case.[82] The preliminary examination must be completed within two to five months, though in some cases detainees are held much longer.[83] A former police officer who left North Korea in 2008 claimed that if the defendant does not confess the period can be extended for up to one year.[84]

A former police officer familiar with pretrial procedures told Human Rights Watch that he estimated that in 80 to 90 percent of cases the recommendation is to send the accused to trial on charges that would carry a short-term or long-term hard labor sentence, with the majority for long-term hard labor.[85] He said the rest of the cases were dismissed and the accused were sent to short-term hard labor detention centers.[86]

Because the ruling party controls all institutions in North Korea, detainees face a parallel process, a review by the Party Security Committee (dang anjeon wiwonhoi), before a decision to pursue criminal responsibility is finalized.[87] This process has no statutory basis. Instead, it operates in a quasi-judicial system run by the WPK.[88] As in other Communist countries, the ruling party oversees the courts to ensure control of the judiciary and that the courts act in conformity with party rules and policies.[89]

The Party Security Committee’s main role is to implement instructions from the party concerning social order, manage judicial organizations, and ensure the uniformity and consistency of prosecutorial and judicial activities.[90] The committees exist at all administrative levels, including local, city, provincial, and national levels. At the national party level, the committee is chaired by the party secretary and includes the director of the police and the secret police, the chief justice of the Central Court, the chief prosecutor of the Central Prosecutor’s office, and the director of the organization and guidance department of the WPK.[91] The Party Security Committees reportedly meet once every 15 to 30 days, or as needed.[92] The composition of the different security committees may vary depending on the jurisdiction and nature of the crimes.[93]

According to former government officials and former detainees with connections in the WPK who spoke to Human Rights Watch, the Party Security Committee is supposed to review the details of each case, investigate a suspect’s political background, and then decide how to dispose of criminal and political cases.[94] The committee reviews a report prepared by the preliminary examiner, which includes an overview of the case with their recommendation to pursue criminal liability and the list of alleged violations of the law. The committee then considers the political implications, and decides whether to accept or reject the recommendation.[95] According to a former police officer, Party Security Committees accept the recommendation of criminal responsibility in almost all of the cases they receive.[96] This process does not conform to the requirements of the Criminal Procedure Code, thus undermining many of the safeguards provided in theory by the law; the reality is that no matter what the law says, party decisions are superior in the North Korean system.[97]

Once the Party Security Committee approves a case to be sent to the next stage, a male accused’s hair is shaved and a female accused’s hair is cut to ear length. If the accused is later found guilty, the length of the sentence is counted from that day.[98]

At this point the preliminary examination officer has to prepare a written decision of criminal liability with specific findings, including reference to applicable laws and related penalties, and send this to prosecutors within 48 hours.[99] The preliminary examination officer also has to inform the accused of the decision to pursue criminal responsibility and the right to choose a lawyer within 48 hours.[100] After the accused is informed of the decision, the preliminary examination officer can interrogate the accused within 48 hours, but this can only take place between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. Exceptions can be made, but in such cases a prosecutor has to be present.[101]

If the preliminary examination officer concludes there is enough evidence to send the accused to trial and the prosecutor agrees, the officer informs the accused, shows the accused the case file, and asks if the accused has any questions or requests to fix errors.[102] The preliminary examination office then writes a report and submits it, along with all case files and evidence, to the prosecutor.[103]

Prosecution

After the preliminary examination officers send a case to a prosecutor, the law requires a prosecutor to “conduct a full review of the case records of the finalized preliminary examination and hand over the criminal case to the court if it recognizes that all details of crime have been completely and accurately revealed during the preliminary examination.”[104]

The prosecutor is supposed to process the case within 10 days, with a possible five-day extension.[105] When the alleged crime is punishable with short-term hard labor the prosecutor has only five days to process the case.[106] If the prosecutor considers the evidence sufficient, the prosecutor submits a written indictment, the case records, and the evidence to the court.[107]

Three former government officials said that while prosecutors do review cases, this is almost a symbolic step and almost all cases are sent to trial.[108]

Trial

The objective of the first-instance trial hearing is “to confirm crimes and criminals and to analyze them based on the law and make a court ruling.”[109] The court of first instance is constituted by a presiding judge and two “people’s assessors.”[110] The presiding judge is required to examine the evidence and determine whether the investigation and preliminary examination process were complied with, whether the appropriate articles of the criminal code were applied correctly to the crime, whether there are criminal conspirators who were not charged, and whether the principles and procedures set forth in the criminal procedure code were followed correctly.[111] At the trial, the prosecutor is tasked to “clearly and scientifically” prove the crime of the accused and whether the trial is conducted in accordance with the law.[112]

The court must conclude the trial within 25 days, with the possibility of a 10-day extension, after receipt of the charges.[113] Proceedings against those accused of crimes punishable by short-term hard labor must be completed within 10 days.[114]

Following a guilty verdict, a convict can file an appeal within 10 days of the receipt of a copy of the written decision (within three days for short-term hard labor sentences). [115] The appeals court is required to review and make a decision on the case within 25 days of receiving the appeal request (within seven days for short-term hard labor sentences).[116] Appeals are rare, as they risk a harsher sentence and because an appeal is considered to be a challenge to the decision by the court and the WPK.[117]

North Korean Courts

North Korean law states that in administering justice “the courts are independent and judicial proceedings shall be carried out in strict accordance with the law.” Yet it goes on to state that the Supreme Court, the highest court in North Korea, is accountable to the Supreme People’s Assembly and to its Presidium when the SPA is not in session.[118]

The lowest court that hears most first-instances cases in North Korea is the People’s Court, which has jurisdiction at the city and county (gun) levels.[119] However, for cases related to political crimes against the state and the nation, the court of first instance is the Provincial Court, the high court of a province.[120] In cases in which there is the possibility of the death penalty or a life-term of hard labor, the Provincial Court again has jurisdiction. The Provincial Court also retains the discretion to try a case falling under the jurisdiction of the People’s Court or to transfer a case to another People’s Court. Generally, the People’s Court is the first-instance court and the Provincial Court hears appeals from the

People’s Court.[121]

North Korea also has three special courts, the Military Court, the Military Logistics Court and the Railway Court.[122] The Military Court tries criminal cases committed by members of the military or the police or cases that affect military activities, while the Military Logistics Court tries criminal offenses committed by employees of the military logistics department or that affect the military transportation business. The Railway Court tries offenses committed by employees of the railway transportation industry or that disturb the railway transportation business.[123]

The Supreme Court hears cases on appeal and cases contesting first-instance decisions by the Provincial Court and special courts. The Supreme Court can directly hear any first-instance case or transfer a case to another court of the same level or type as the court of original jurisdiction.[124]

Although there are three regional levels of courts, the North Korean court system allows for only one appeal. Moreover, because the Supreme Court has the power to hear first-instance cases without any appeal, the benefits of the two-instance system may be nullified at the will of the court.[125]

Quasi-Judiciary System

In addition to the system described above, North Korea operates a separate quasi-judicial system to exercise control over its people.[126] This system is opaque and complex. Parts of this system are based on party decrees and structures, such as the Party Security Committee or the Organization and Guidance Department from the WPK Central Committee mentioned above, and some are secret, such as those related to the Ministry of State Security or the Military Security Command.[127] Others, such as the “Socialist Lawful Lifestyle Guidance Committee,” have a legal basis.[128] This committee is in charge of processing administrative penalties and petitions.[129] It also “oversees the country’s leading economic agencies and their leading workers so they don’t abuse their power and work observing the socialist laws and regulations.”[130] It is also organized at the central, provincial, city and local levels, under the supervision of the People’s Committees. At the central level, Socialist Lawful Lifestyle Guidance Committees appear to include five or six members including the head of the party guidance committee, the party organization director, the director of People’s Safety, and the head of the Prosecutor’s Office. At the provincial and regional levels, it includes the heads and deputy head of the Peoples’ Committee, the head of the police, the Prosecutor’s Office, and a member of the legal department.[131]

The treatment of ordinary crimes and political crimes is strictly divided. Political crimes are considered anti-state and anti-nation crimes committed by enemies or “counter-revolutionaries” against the party and government. These cases are under the jurisdiction of the secret police, and the Military Security Command when connected to the army.[132] Though certainly broad, the exact powers of the Ministry of State Security are secret and therefore unclear.

North Korean citizens who have allegedly committed severe anti-state or anti-nation offenses disappear and are sent to political prison camps (kwanliso) without notice, trial or judicial order.[133] There, they are held incommunicado, subjected to torture, forced labor and other severe mistreatment, and their families are not informed of their fate even if they die.[134]

Corruption and Law Enforcement

After the Great Famine of the mid-1990s, private markets (jangmadang) became an alternative to the public distribution of food and a source of income to stave off starvation. As trading was still technically illegal, government officials and people in positions of power, including police and secret police officers, detention and interrogation facility guards, prosecutors and party officials, saw opportunities to demand bribes to avoid detention, arrest and prosecution.[135] Bribes soon became an important source of income for many of those in power. According to the COI, government officials “are increasingly engaging in corruption in order to support their low or non-existent salaries.”[136] According to Transparency International’s 2019 Corruption Perception Index, North Korea ranked 172 out of 180 countries.[137]

Despite this, interviewees told Human Rights Watch those in positions of power are careful about taking bribes and would return or reject money or gifts in some cases.[138] A former police officer told Human Rights Watch: “We [government officials] also have our morals and we only get [bribes] when we can deliver.” A former trader explained that “government officials are very careful on who they get bribes from, and only keep [the money] when they can give what they offered or have been asked for. They don’t want somebody blabbing around, word could get out there, threaten their reputation or future possible income, or end up triggering an investigation of the officer himself [for corrupt practices].”[139]

III. Pretrial Detention Facilities in North Korea

Detention facilities that the North Korean government acknowledges include:

- Jails: small cells in small or remote security and law enforcement agency offices, gugumsil, literally “detention room” or daegisil, literally “waiting room”.[140]

- Detention and Interrogation facilities (kuryujang, literally “place of detention”): facilities that include security and law enforcement agency offices, rooms where detainees undergoing investigation and/or preliminary examination (yesim) are interrogated, and cells where they are held during that period. Those cells are also used to hold detainees awaiting trial; to be transferred to their home districts; to be sent to long-term hard labor ordinary crimes prison camps; or to be executed.[141]

- Temporary holding facilities (jipkyulso, literally “gathering place”): located mostly near the Chinese border, they are used to temporarily detain people forced back after crossing the border, or for violating domestic travel restrictions. Detainees are held here until a law enforcement officer from the area where they are registered as residents picks them up and escorts them back to their hometown.[142] Some detainees may be required to engage in forced labor and others may carry out short-term hard labor sentences for up to a year.[143] The use of these facilities as a place for punishment does not appear to have any legal standing or clear time limits on how long a person may be detained.[144] The facilities may be run by the police, secret police, or army.[145] The COI found that conditions in temporary holding facilities were inhumane and that authorities implemented a policy of imposing deliberate starvation on detainees.[146]

- Short-term unpaid hard labor detention centers (rodong danryeondae, literally “labor training centers”): the most common detention centers for misdemeanors with short-term sentences with less than one year of hard labor.[147] They are generally run by the People’s Committees of the WPK at the provincial, city and district level.[148]

- Short-term unpaid hard labor police detention centers (boanseong danryeondae): detention centers run by the police at the national level for crimes sentenced to short- term (six months to one year) hard labor criminal penalties (rodong danryeonhyung).[149] These centers are adjacent to hard labor ordinary crimes prison camps (kyohwaso).[150]

The 2014 COI found that torture, deliberate starvation, inhumane treatment, and sexual violence were systematically imposed in detention and interrogation facilities, especially in detention facilities that initially receive persons forcibly returned by China.[151] It also found that police and secret police systematically used severe beatings and other forms of torture during questioning until the interrogators were convinced that the accused had confessed to the totality of his or her wrongdoing.[152] It also stated that the treatment of suspects is particularly brutal and inhumane in centers of the secret police, where suspects are typically held incommunicado in inhumane conditions in order to exert “additional pressure on detainees to confess quickly to secure their survival.”[153]

The North Korean government has repeatedly rejected the findings of the COI, contending that there are no prisons in North Korea.[154] Instead, offering a distinction that has no practical effect, the government contends that criminals are held in labor reform institutions where they are held for “reform through labor” (rodong kyohwa).[155] These reform through labor centers (rodong kyohwaso), which are de-facto long-term hard labor prison camps, are run by the police to hold perpetrators of serious ordinary crimes and minor political crimes with sentences of “reform through labor criminal penalty” (rodong kyowhahyeong) for a limited term (yugi rodong kyohwahyeong) between one and 15 years, or a “reform through labor criminal penalty for life” (mugi rodong kyohwahyeong).[156]

The North Korean government also strenuously denies the existence of penal hard labor colonies for serious political crimes—in effect, political prisoner camps—called in Korean kwanliso, literally “control centers,” which are considered a state secret.[157] These camps are run by the secret police. Political prisoners, and in some cases their whole families, are often forcibly disappeared, held incommunicado, and detained in these camps.[158] Prisoners in “reform through labor centers” and “control centers” are subjected to crimes against humanity, face brutal and inhumane conditions, arduous forced labor, malnutrition, and starvation due to insufficient food rations.[159]

IV. Abuses in Pretrial Detention and Interrogation Facilities

Beaten and Abused

Mistreatment in custody is a standard feature of the criminal justice system in North Korea. Twenty-two former detainees and eight former government officials told Human Rights Watch that mistreatment of detainees is especially harsh in the early stages of questioning in pretrial detention and interrogation facilities (kuryujang).[160] The former officials explained that the authorities consider harsh treatment to be necessary to obtain confessions, which are crucial in the interrogation process during the investigation and preliminary examination stages.[161] They added that humiliation and mistreatment are considered important to preempt future crimes by detainees.[162]

A former police officer involved in the detention processes told Human Rights Watch:

The regulations say there shouldn’t be any beatings, but we need confessions during the investigation and early stages of the preliminary examination. The detainees have confessed all the crimes they committed, and they need to write their self-criticism documents as many times as necessary, one time or ten times. So you have to hit them in order to get the confession. [One] can hit them with a pine stick or kick them with the boot. It is the only way to get their finger stamp at the end of the finalized document ... even after the investigation process is finished, if they later deny it or not confess again to the preliminary examiner, we’ll hit the detainee and think this person might be out of their mind.[163]

He related that in the beginning, outside food is not allowed, the same as cigarettes, or other things that may make detainees be more comfortable. Those are only allowed after the confession and the necessary documents are almost finalized. He added that:

Even for those who are innocent and end up being released, being held in the detention and interrogation facility must be re-educational, and for that they need to have a very hard experience, that is humiliating, so they become like machines and make the clear decision never to commit crimes again.[164]

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that on a typical day detainees are awakened at detention and interrogation facilities between 5:30 a.m. and 7 a.m., eat breakfast, and then sit immobilized, in the manner described below, until the half-hour break for lunch (noon) and dinner (5:30 p.m. or 6 p.m.) and bed time at 10 p.m., with theoretical breaks of 10 to 30 minutes every two hours.[165] All North Korean interviewees who were held at detention and interrogation facilities, as well as eight former government officials we interviewed, told Human Rights Watch that all detainees were forced to sit still on the floor, kneeling or with their legs crossed, their fists or hands on top of their laps, their heads down, and their eyesight directed to the floor—for 7-8 hours and in some cases up to 13-16 hours a day.[166] If a detainee moved, guards would punish the detainee or order collective punishment for all detainees. The punishments included hitting the detainees with their hands, a thick wooden stick, a leather belt or other objects, kicking them with their boots, making them sit down and stand up, do push-ups, or run in circles in a yard repeatedly, sometimes 100, 300, or even 1,000 times.[167]

The 22 former detainees and four former government officials told Human Rights Watch detainees were forced to keep their gaze towards the floor and were not allowed to look at the face of the guards, investigators, or examiners.[168] Ten former detainees and two former government officials said they had to refer to themselves by their given code number, not their names.[169] They said this was because detainees were considered inferior beings and were not worthy of direct eye contact or of using their own names.[170]

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that individual interrogation sessions took place in separate closed-door rooms without witnesses by male investigators or preliminary examiners (police, secret police, or prosecutor).[171] The former detainees said the interrogators asked similar questions about the case being investigated over and over, and asked the suspects to produce written confessions to their alleged crime repeatedly.[172] If the stated or written testimonies had any discrepancies the interrogators asked them to repeat or write the account again, sometimes several times a day for several days, and punished the detainees.[173] The former detainees said that during questioning they suffered physical violence, including being punched by officers, hit with a thick wooden stick or a thin rod, or kicked with boots.

The testimonies received by Human Rights Watch are in line with the findings of the UN COI, which found that “inmates (held in detention and interrogation facilities run by the secret police), who are not undergoing interrogations or who are not at work, are forced to sit or kneel the entire day in a fixed posture in often severely overcrowded cells. They are not allowed to speak, move, or look around without permission. Failure to obey these rules is punished with beatings, food ration cuts or forced physical exercise. Punishment is often also imposed collectively on all cellmates.”[174] It also found conditions in detention and interrogation facilities run by the police are “similar to that of [MSS] detention, except that suspects are often allowed to receive occasional visits from family members.”[175]

Some female detainees reported that they experienced or observed sexual violence, including rape in detention and interrogation facilities.[176] Interviewees said that agents from the police, secret police, and the prosecutor’s office, most in charge of their personal interrogation, touched their faces and their bodies, including their breasts and hips, either through their clothes or by putting their hands inside their clothes. They said they were powerless to resist because their fate was in the hands of these men.[177]

Case of Heo Yun Mi

Heo Yun Mi, a former accountant in her 50s from South Hamgyong province, escaped North Korea in late 2015. She told Human Rights Watch that because her daughter had attempted to escape to South Korea she was detained for a week in early 2015 at a detention and interrogation facility (kuryujang) run by the secret police. She said she was forced to spend the entire time sitting on the ground in line, with her legs crossed and her hands on her knees, except when she was being questioned, had a break, was eating or was being punished.[178] She said that officially they had 5-10 minute breaks in the morning and the afternoon, but whether they got them depended on the mood of the guards. They were monitored by a camera. She explained:

Guards watched us sitting in lines through the CCTV. Suddenly they’d speak through the speaker and say, ‘Cell X, detainee Y, get up.’ […] Sometimes they’d punish the whole room, but it depended on the guard, one out of ten was nice, but most were horrible.… The punishment was getting up and extending the arms to the front, or to the top for a long time. Or getting up and sitting 20 times, or 100 times or more. Punishment for moving would happen once a day, as people were busy being sent for questioning. If you kept moving after being punished, the guards would hit you with a club in the hands. They would also hit you if you didn’t apologize and beg when being punished. Men’s cells had more violence, and sometimes they asked the detainee chief to hit other detainees.… We had to call the guards ‘teacher.’ When we went out of the cell to get questioned, we had to bend our bodies 90 degrees as we walked, our gaze towards the floor while being questioned, never able to look straight at the guards. They’d beat us according to the regulations if we did. Detainees were called by a name like ‘Cell X, number Y.’ Guards would refer to us with insults like, ‘You fucking whatever.’

Heo Yun Mi explained that the secret police questioned her for six days. They beat and tortured her for three days. She recounted:

Mainly the investigator hit me with his palm in the cheek. In the beginning, after [the investigator] hit me, I couldn’t hear well. I heard they mainly beat women in the face, but if they didn’t like your statement, they’d also hit them with a stick.

Heo Yun Mi’s daughter was also detained in the same facility around the same time. The daughter told Heo Yun Mi that she had been questioned for two days for her attempt to cross to China by the secret police, but they only beat her on the first day. Heo Yun Mi explained:

I was sitting in a chair during questioning, but my daughter told me she had to sit on the floor kneeling and there was another person who was being questioned at the same time as her and she was sitting on a chair.

Heo Yun Mi also described how a woman held in her cell “had been questioned while kneeling on top of the heater and had been burned. They also hit her with a stick in the calves.... There was a military doctor, the woman who got burned was treated by the doctor.” She also recalled that a male colleague from her work was detained at the same detention and interrogation facility run by the secret police in June 2015 for one month and could not walk properly after he was beaten.

Case of Park Ji Cheol

Park Ji Cheol, a former lumberjack in his 20s from a bordering province with China who left North Korea in late 2014, was detained in detention and interrogation facilities run by the police twice, in 2010 and in 2014.[179] He told Human Rights Watch that on many occasions he managed to avoid detention because his uncle, who was a large-scale smuggler, often gave gifts like corn-based liquor, cigarettes, mushrooms, or cash to police officers, soldiers, and MSS officials to facilitate his activities. In 2014, he was held in a police detention and interrogation facility for three days for not going to work at a government-sanctioned workplace and was then sent to a hard labor detention center for three months.

In 2010, he was also detained for smuggling, this time for almost one year, at a detention and interrogation facility. After an investigation and preliminary examination, he was sentenced to five years of hard labor at an ordinary crimes prison. Because his uncle was able to pay bribes to the right people, Park Ji Cheol ended up serving just one year before receiving a general pardon following the death of the former North Korean leader Kim Jong Il.

The detention and interrogation facility where Park Ji Cheol was held had nine separate cells. Men and women were held separately. He stayed in a 15 square meter cell holding between 13 and 16 cellmates. The detainees remained in their cell, unable to move, except when questioned by the investigator or the preliminary examiner in charge or when given permission to move by the guards. The detainees slept on the floor from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m., when the police guards woke them up and brought in a large bucket with water, which all cellmates used to wash their faces and to drink. The guards provided breakfast at 7 a.m., lunch at noon and dinner at 6 p.m. for 30 minutes. Every two hours, there was a change of guards who gave cellmates 10 to 30 minutes to walk outside to the yard or to stand. According to Park Ji Cheol:

Every single day was horrible, so painful and unbearable.… Many times, if I or others moved [in the cell], the guards would order me or all the cellmates to extend our hands through the cell bars and would step on them repeatedly with their boots or hit our hands with their leather belts. Even then we weren’t allowed to move. If we responded and they didn’t like us, they’d beat us up.

Park Ji Cheol said that after the investigation process was over, the guards allowed his family members to pay some bribes to allow them to bring food once a week. He said:

The food from prison was terrible and so little. I was hungry all the time. They gave us three meals a day, a handful of crushed and boiled corn, around 70 grains of soybeans per meal, which they said was very nutritious so we wouldn’t get sick from weakness, and a soup made with boiled wild greens.… You can’t survive with the food there. If the family visits, you eat. My mom could come once a week, she brought white rice enough for one meal, also corn powder that mixed with water becomes corncake. I’d eat this with the rice and wait for the next visit during the whole week.

He said the men detained with him were at different stages of the criminal process. Some were still under investigation, others were undergoing preliminary investigation or waiting for trial, and others had already been sentenced and were waiting to be transferred. Two detainees were waiting to be executed. He said:

Two of my cellmates were sentenced to death after trial. The guards kept them in the detention and interrogation facility for 90 or 100 days. They just existed, they were a human shell, but were watched closely so they couldn’t commit suicide. Afterwards, they executed them…. Five people died while I was there. In February 2010, one woman was [accused of] killing and eating her child because of hunger, right after the currency reform [2009] when many people suffered. She died of starvation, she was only skin and bone. In June 2010, a man who went into a house to steal took 2.5 kgs. of rice and NKW5000 [worth 8 kgs. of rice at the time][180] from a house and killed the woman living in the house. He died also of hunger. Another detainee died after being detained for consumption of ‘ice’ [methamphetamines, also called bingdu in North Korea].

In 2014, Park Ji Cheol was detained for three days at a police detention and interrogation facility. He told Human Rights Watch:

The detention and interrogation facility was the hardest. You had to sit still all day. I could only think of when I was detained the last time. I remembered after two months, I just wanted to kill myself, but I couldn’t. The day the [official] three months [extension] finished I was going crazy, I thought I’d be released then.... This time the police investigator quickly prepared the investigation document and sent me to three months at a hard labor detention center.

Case of Kim Sun Young

Kim Sun Young, a former trader in her 50s from North Hamgyong province, escaped North Korea for the last time in 2015. However, she suffered badly after being forcibly returned from China at the end of 2012.[181] She said she was sent to at a detention and interrogation facility run by the secret police near the border for a few days and after establishing that she did not commit serious political crimes was transferred to one run by the police in her hometown. She was held for five months and then sentenced to five years of hard labor at an ordinary crimes prison camp with two-and-a-half years suspended because of the bribe her son managed to pay. In the end she spent five months at the police detention and interrogation facility, followed by almost two years at the Chongori ordinary crimes prison camp.

At the police detention and interrogation facility, Kim Sun Young was held in a cell less than 12 square meters in size. The cell usually held about 12 detainees, leaving insufficient space to lie down and stretch her legs at night. Men and women were held in separate cells at the facility. She said that detainees were awakened at 7 a.m., washed their faces, and then had to sit immobilized all day for 12 or 13 hours except when they were allowed to move to eat, be questioned, or have a short break. She said:

Beatings were the worst in the detention and interrogation facilities. While waiting to be investigated, we had to sit still. Our hands had to be folded on top of our legs, which had to be crossed. Every hour or every three hours, we could stand for 10 to 30 minutes depending on the mood of the guard in charge.… We had to sit without moving. When I moved, the guard would hit me. If you fell asleep, they’d make you stand and squat up to 1,000 times. You think it is too many and you cannot do it, but if they force you, you can. The body is in extreme pain and you think you’ll die, but you do it. Sometimes, all the detainees are punished with you. People complain and hate it when others move.

She said women were more scared of physical punishment, so the women kept quieter than men and tried to follow the guard’s instructions. But the men were more rebellious and would be beaten more often. Kim Sun Young explained she could not see the beatings, but she could hear the conversations and the insults and degrading comments accompanied with sounds of violence.

Kim Sun Young said a bowiseong interrogator in charge of her case at the detention and interrogation facility raped her, while another police officer sexually assaulted her by touching her body over and underneath her clothes while interrogating her. She said her fate was in their hands and she was powerless to resist.[182]

Case of Kim Keum Chul

Kim Keum Chul, a former smuggler of medicinal herbs in his 30s from North Hamgyong province, escaped North Korea in 2017.[183] He was detained four times in pretrial detention and interrogation facilities between 2000 and 2014: once in the bowiseong detention and interrogation facility in a town bordering China and three separate times in a police detention and interrogation facility in his district bordering China. In each case he was able to shorten his time in detention after paying bribes.

Kim Keum Chul’s first experience in detention under the secret police was in 2000, where he was held for just over a month for smuggling. He said he was beaten every time he was questioned. He explained that as it was a case with possible connections to Christian missionaries in China, the beatings and mistreatment were more severe, since cases connected with Christians are considered to be serious political cases. He said: