How is it that 50 percent of Australia’s prison population has a disability?

Eighteen percent of Australia’s general population has a disability. The most common type of disabilities found in prisons are mental health conditions. People with disabilities are not more criminal than anyone else, but the lack of comprehensive mental health and social services has created a pathway to prison for many people with disabilities.

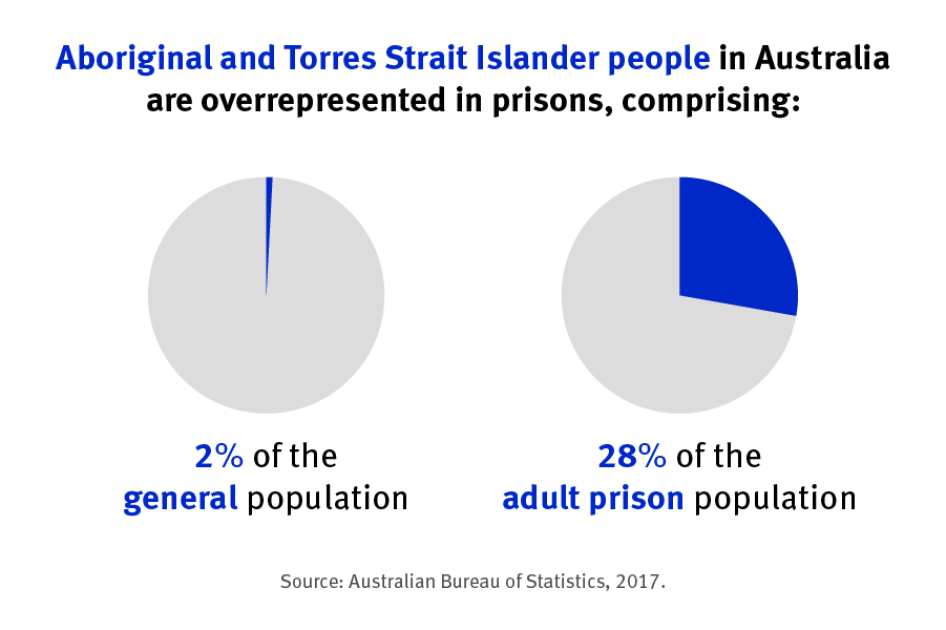

Many are Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islanders. Research shows that most of the offenses they committed are less serious than offenses committed by others – a failure to pay fines, traffic violations, or public order offenses.

What trends did you see for people with disabilities behind bars?

They’re seen as easy targets. Across all 14 prisons, people with disabilities were repeatedly bullied. Other prisoners take away their possessions, cigarettes, medication. The way it happens is the nurse hands the medication out, puts it into your hand, and you swallow it, opening your mouth to show that you actually swallowed it. But after some people with disabilities take their medicine, other prisoners would make them regurgitate it up. If they didn’t, they would get beaten up. One prisoner said he would be beaten up or attacked in the shower, and by the time the guards came, it was too late, he was already bashed. So he just gave in.

Some prisoners with disabilities are manipulated to do the bidding of other prisoners. If they try to resist, they will be threatened or beaten up.

Also, both male and female prisoners with disabilities faced physical and sexual violence, not just from prisoners but also from staff. In Australia’s prisons, a “prison-carer” is another prisoner, paid by the prison, to help people with disabilities with things like going to the bathroom or making their bed. We documented cases where the carers were sexually abusive. There’s such a power imbalance that the people with disabilities are afraid to report it. One case was uncovered by staff when they found blood and feces on the bed, and they started asking questions.

Prison officials said they go through great lengths to choose these carers. But a senior nurse in a prison said that some of the carers there were convicted of a sex crime.

Your research shows that prisoners with disabilities are also more likely to be placed in solitary confinement. Why is this?

It took us some time to uncover the frequent use of solitary confinement. They don’t use those words in prisons Australia. They say “separate confinement” or “segregation.”

Under international law, solitary confinement is being locked up in a room for 22 hours or more per day without meaningful social interaction. Across the prisons I visited you see people with disabilities – particularly mental health conditions -- kept in solitary for days, weeks, months, and sometimes even years.

Even when people are at risk of hurting themselves, they are kept in an observation room or a crisis center – the equivalent of solitary. Solitary confinement is damaging for any prisoner, but for prisoners with disabilities it is devastating.

We understand that prison officials are trying to keep them alive. But when a prisoner goes into this unit, they have no one to talk to. Lights are on 24/7, making it hard to sleep. They have no mental health support. They have to wear a suicide-proof gown, they’re given finger food to eat – so no utensils. All this happens to them when they are having a crisis, when they’re crying out for help. And they experience this as punishment. For some people, it pushes them over the edge.

We saw medical files from mental health professionals that say holding people in solitary confinement is extremely damaging, but they’re not heeded. The files say the patients would get better if they were out of solitary.

It’s even more damaging for Aboriginal people, because culturally family and community is so important.

We documented cases where prisoners went into these units and their condition deteriorated. They ended up in the hospital. A prisoner with a mental health condition told us he was verbally and physically abused by prison staff while in solitary, and then he started hurting himself, all because he wanted someone to speak to. “I was sobbing, they didn’t respond. They opened up the grate [in the cell door] and laughed at me. I swallowed batteries in front of them,” he said. “I started playing up [because] I needed to talk to someone but they ignored me.” He ended up being shackled and taken to the hospital. Being ignored pushed him over the edge.

Why do staff do this?

Staff need better training to identify people with a disability. Right now, many staff misinterpret the behavior of these prisoners as being defiant and disobedient, and instead of giving them the assistance they need, they punish them.

Also, institutionalized racism against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is so common and accepted that it’s not reported by prisoners. One woman with a mental health condition disability told me, “officers call me ‘black cunt’ heaps of times. It’s normal.”

How did you research this report?

We got unprecedented access to 14 prisons across Western Australia and Queensland and interviewed 275 people, including 136 prisoners with disabilities. Many of our partners haven’t gotten such access. The Commissioners of Corrective Services of both those states know that dealing with prisoners with disabilities is challenging and were keen to get our input.

What was it like for you, going into these prisons?

In prisons, security is the number one priority. You leave your phone in a locker, take your shoes off when you go through security. You can only take a notebook and pen in with you. You’re handed a panic button – if you press it, guards would come running in seconds. You’re escorted everywhere. And you only have a very limited window to talk to people.

There’s a subculture, and a prison lingo, you have to pick up. Officers are called “screws.” “Dog” means traitor. They don’t say they were “bullied,” prisoner say they’re “stood over.” It takes a while to learn that and to build a rapport with prisoners. It was challenging research because prisoners are so scared to report abuse, and because you have very limited time to explain who you are and what you’re doing and why they should confide in you. The same went for interviewing prison staff.

Being from India myself, it was easier. I think many of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people felt I was culturally closer to them than a white Australian would be.

Human Rights Watch has also researched what happens to prisoners with disabilities in the US and France. How does Australia compare?

There were a lot of similarities with the abuses that African-Americans and Latinos in the US face. They’re over-represented in prison, they face racism and barriers to justice. On the disability front, it’s also similar. When prison staff don’t understand disabilities, they take punitive action. In the US, it leads to an excessive use of force. In France, it was the overuse of medication. And in Australia, it’s the use of solitary. But at the root of it, there’s inadequate training and access to appropriate support services.

What changes do you want to see?

In addition to training staff, we want regular and independent monitoring of prisons. This system exists in four states, but we would like it in all. We want an end to solitary confinement for prisoners with disabilities, and a first step would be for national or state-level inquiries into this issue. It’s also important for people’s disabilities to be screened when they enter a prison. Right now, people are asked to self-report disabilities, and many people – particularly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – don’t know they have a disability. Some feel shame and don’t report it. If the disability is not identified, people may not get the support they need.

This interview has been edited and condensed.