Hundreds of men buried alive, men and women mutilated and slaughtered, children killed before their mothers’ eyes, a grandfather forced to eat the liver of his own grandson. These are truly scenes from hell, written on the darkest pages of human history.

This chilling description of the Srebrenica genocide was written by a judge at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in the Hague in November 1995, only months after Europe’s worst crime since the Second World War. In July of that year, Bosnian Serb forces seized control of the Srebrenica enclave — a designated United Nations safe area — from international peacekeepers. They separated the men and women and in the days that followed killed more than 7,000 men and boys.

As Ratko Mladic, the wartime commander of Bosnian Serb forces, begins his life sentence as an architect of those crimes and with the court that convicted him having closed on December 21 after almost a quarter of a century, it’s a good moment to look at the tribunal’s achievements — and its limits.

A Success on Its Own Terms

The break-up of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia that began in 1991 unleashed a series of wars — in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and later in Kosovo and Macedonia.

The bloodiest of them, in Bosnia, gave birth to a new phrase “ethnic cleansing,” because of the deliberate forced displacement of civilians belonging to a particular ethnic group to create ethnically homogenous areas. The world watched in horror as Bosnia’s capital, Sarajevo, was besieged, its people shot by snipers as they went to gather water or firewood.

The unfolding atrocities documented by a UN commission of experts, nongovernmental groups, and journalists led the UN Security Council to set up the court in 1993 with a simple purpose: “prosecuting persons responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia.”

On that score, it has been a remarkable success. All of the court’s 161 indictees — including many top wartime political leaders and military commanders — faced justice before it for horrific crimes including the Srebrenica genocide, or have died.

The tribunal’s success was not a foregone conclusion. While it was hoped its mandate would help deter abuses and bring those responsible for the worst crimes to justice, the tribunal was slow to make good on those promises. Building on the work of the UN commission, it gathered evidence and issued indictments. But lacking a police force, it had difficulty getting those it indicted into the dock in The Hague.

In 1997, two years after the end of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the tribunal had only eight suspects in custody, most of them “little fish.” More than 50 remained at large in Bosnia, and the prospect of arresting high-level suspects seemed remote.

That changed because of the efforts of human rights groups, including Human Rights Watch, and supportive governments, first through pressure to get the NATO peacekeepers in Bosnia to arrest suspects in that country, and later though political pressure on Croatia and Serbia by the EU and US to hand over suspects on their territory.

As time marched on and diplomats’ memories of the grim human rights violations faded, it became harder to get the EU to remain firm on the conditions it had set for possible membership by Serbia and Croatia, including turning over suspects. Some EU governments wanted to embrace Croatia and Serbia without any guarantee of the handover of key suspects.

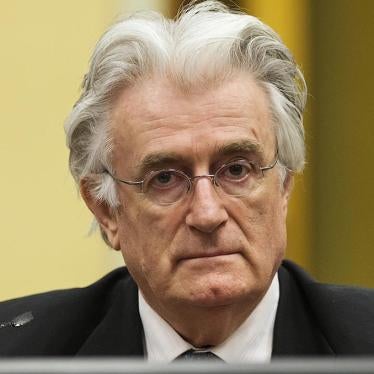

But ultimately, with non-governmental groups pressing the issue and magnifying the voices of victims, media scrutiny, and the fortitude of the Netherlands and a handful of other EU states, the EU held firm. That meant that the big targets — including the Croatian general Ante Gotovina, the Bosnian Serb wartime president Radovan Karadzic, and Mladic — were eventually arrested and sent to The Hague to face justice.

Justice Isn't Perfect, But It's Possible

Through its work, the ICTY gave life to the idea that justice is possible, and can reach the untouchable, even if its realization seems impossible while conflict is raging. It helped develop international criminal law in relation to genocide, crimes against humanity, the responsibility of commanders for the crimes of their subordinates, and rape and sexual violence in conflict as war crimes.

The ICTY also contributed to the momentum that led to the creation of the International Criminal Court to tackle impunity around the world. So far, 123 states are members of this court, which is currently investigating atrocities in 10 countries. The ICC faces many of the same challenges that plagued the ICTY in its early days, including inconsistent political support (the United States, for example, has refused to join) and cooperation from countries in securing evidence and in arresting suspects.

These ongoing challenges offer a stark reminder of the difficulties of realizing justice for unspeakable horrors. They also illustrate the importance of pressing on, as the victims of these crimes too often have little hope of seeing justice otherwise.

The ICTY was not perfect, of course.

Crimes against minorities during and after the 1998-1999 conflict in Kosovo arguably didn’t get enough attention, and the cases that were brought were undermined by witness intimidation. The court was slow to make its judgments known and understood across the region, which left space for hostile politicians to sow misperceptions about its work.

The tribunal’s judges sometimes struggled to strike a balance between fairness to defendants and efficient prosecution of the trial, with defendants like former Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic using the courtroom to broadcast political messages to audiences at home and dragging out their trial for years. Milosevic infamously died before the court issued its verdict. That led to understandable — and intense — disappointment and frustration for victims and their families.

Ongoing Divisions

While the ICTY was ultimately a success in accomplishing what the UN Security Council established it to do — prosecuting and trying some of the key architects of the wars in the former Yugoslavia — its impact and legacy in the Western Balkans is mixed.

Critics point to the deep divisions that remain in the region, especially in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as evidence of the court’s failure. Many of the foot soldiers who carried out the atrocities as well as mid-level commanders remain free, and the domestic war crimes prosecutions that were supposed to deal with them have been slow and limited in scope. Politicians in some communities have successfully characterized the ICTY’s conviction of their wartime leaders as evidence that it is an instrument of persecution, feeding into existing narratives of victimhood.

The critics are mostly right on the facts, but mostly wrong to pin the blame on the ICTY. The court’s registry woke up too late to the importance of outreach, by which time the region’s political leaders had already established their own poisonous narratives. And it perhaps could have transferred the evidence and skills to local prosecutors and courts sooner to build national capacity for war crimes justice, although lack of political and financial support from Bosnia’s international partners is arguably a much more important factor.

But those who malign the ICTY’s failure to bring reconciliation and end political division in the region had outsized expectations of what it could deliver. A better question to ask is this: How would the region and its politics look today without the ICTY? As difficult as things are in the region today, they would have been incalculably worse had leaders responsible for unleashing and directing horrific political violence remained in office and in command.

A More Comprehensive Approach

To help heal the political divisions in the region and move toward reconciliation, the Western Balkans needs a regional truth commission, a goal long pushed by nongovernmental groups. And governments in the region need to intensify efforts to prosecute war crimes in local courts. That requires the EU, the U.S., and other international actors to invest the political and economic capital to make it happen.

Now that the ICTY has pulled down the shutters, the urgency of pressing for a more comprehensive approach to documenting the truth is even more apparent. The Western Balkans has far too long been neglected by the EU and United States. The joint statement by the EU High Representative and US Secretary of State on December 5 on the importance of reconciliation in the region should signal an intensification of EU and U.S. support for those efforts.

The ICTY has had a necessary and important, even if limited, impact on establishing the truth behind those bearing responsibility for the atrocities and devastation that followed the onslaught of the wars in the Balkans. Its closure only underscores the importance of supporting and continuing the hard and necessary work to bring full justice and reconciliation to Western Balkans.