What are the charges against him?

It's been more than 14 years since his initial indictment. Why is his trial important?

Why hasn't Karadzic's co-accused, Ratko Mladic, been arrested?

Doesn't Karadzic claim that he was promised immunity from prosecution?

How is Karadzic handling his defense?

If Karadzic is representing himself, how is he managing such a complex case?

Hasn't Karadzic threatened to boycott his trial? Can the trial still move forward?

How will victims know about what is going on in The Hague?

Are there lessons for the Karadzic trial from the tribunal's trial of Slobodan Milosevic?

How long is the trial supposed to last?

Isn't the tribunal supposed to be shutting its doors?

What if Mladic is captured after the tribunal has completed its work?

Given Karadzic's persistent refusal to attend, may the trial proceed?

Does that mean that Karadzic has been stripped of his right to represent himself?

Did Karadzic select his counsel?

Will Karadzic's trial resume on March 1? Isn't he seeking a postponement?

Who is Radovan Karadzic?

Radovan Karadzic was a founding member of the Serbian Democratic Party of Bosnia and Herzegovina. He was the president of Republika Srpska, the Bosnian Serb entity, during the war in Bosnia, from 1992 to 1995. Karadzic was indicted for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. Karadzic has notified the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) that he does not intend to appear for the start of his trial on Monday, October 26, 2009.

What are the charges against him?

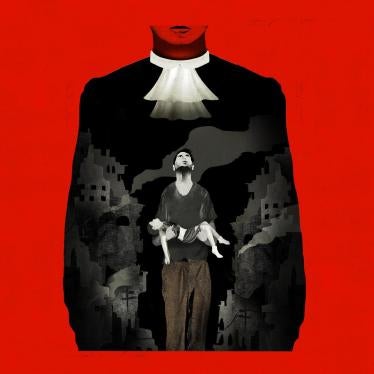

Karadzic and his co-accused, the Bosnian Serb wartime general Ratko Mladic, are charged with genocide as architects of the killings of at least 7,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys following the July 1995 seizure of the Srebrenica enclave - a designated UN "safe area" - from NATO and UN troops by Bosnian Serb forces. The Srebrenica genocide was the worst crime committed on European soil since World War II.

Karadzic also faces a separate genocide charge for killings, rapes, torture and other acts committed by Bosnian Serb forces against Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats between March and December 1992 in a number of municipalities. According to the prosecution, the goal was to remove Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats permanently (sometimes called "ethnic cleansing") from areas in Bosnia the Bosnian Serbs claimed as their territory.

Karadzic faces nine further charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity for other wartime abuses committed by Bosnian Serb forces, including murders, deportations, attacks on civilians, and the taking of international hostages.

The Yugoslav tribunal initially indicted Karadzic in 1995. In mid-1996, the trial chamber issued international arrest warrants for Karadzic and Mladic, who remains at large. Karadzic disappeared from public life until he was finally arrested by Serbian authorities in July 2008.

It's been more than 14 years since his initial indictment. Why is his trial important?

Karadzic is one of the highest-level officials to be held to account by the Yugoslav tribunal, and he is accused of being one of the masterminds behind the most serious crimes committed during the Bosnian war. He is charged with two counts of genocide, meaning he allegedly intended to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. This trial should help uncover the truth about his role. Genocide, the most serious crime under international law, is hard to prove, but it is hoped that, whatever the outcome, the trial will finally offer victims the sense of justice that they have been waiting for since the war.

Karadzic's arrest and trial also shows others who are responsible for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide or who are contemplating such acts - whether they have been indicted by the Yugoslav tribunal, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda or the International Criminal Court - that they can no longer simply expect to "run out the clock" on justice.

Why hasn't Karadzic's co-accused, Ratko Mladic, been arrested?

The fact that Mladic has not yet been arrested exposes the "Achilles heel" of international justice: without its own police force, this tribunal and other international criminal tribunals must rely on the cooperation of individual countries to arrest and surrender suspects. Most of the defendants who are or were in the tribunal's custody were handed over by the authorities in the region or apprehended by international peacekeepers in Bosnia, with only a small number surrendering voluntarily.

Serge Brammertz, the tribunal's prosecutor, said in his most recent report to the UN Security Council, that Mladic is "within reach" of Serbian authorities, who have repeatedly undertaken in recent years to apprehend him and transfer him to The Hague. Consistent pressure by the European Union (EU), using the prospect of EU membership, has been a vital tool in the arrest and surrender of high-ranking defendants. Indeed, the arrest and transfer of Karadzic by the Serbian authorities demonstrates that EU pressure can deliver results. EU pressure also played a crucial role in persuading the Croatian authorities to cooperate in the capture and surrender of General Ante Gotovina to the tribunal in 2005. The EU should continue to use its valuable leverage to pressure Serbia to deliver on its promise to arrest and surrender Mladic and Goran Hadzic, the other remaining fugitive, to The Hague.

Doesn't Karadzic claim that he was promised immunity from prosecution?

As part of his defense, Karadzic has alleged that in mid-1996, Richard Holbrooke, then the top US negotiator, promised that Karadzic would not have to face prosecution in The Hague if he agreed to withdraw completely from public life, and that this promise is binding on the tribunal. Holbrooke has denied the allegation.

Karadzic raised this issue initially in late 2008, when he asked judges at the tribunal to order the prosecution to disclose documents that Karadzic asserted would help prove the existence of such an immunity deal. Judges ordered the prosecution to disclose some of the documents requested. However, the ruling also made clear that any immunity agreement for a defendant indicted for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide before an international tribunal would be invalid under international law, and therefore could not be relevant to preparing Karadzic's defense. Moreover, the tribunal noted that should such an alleged agreement exist, it would have no impact on the mandate of the tribunal or the prosecutor. The documents requested would therefore only be relevant to demonstrate behavior on the part of the accused that could be considered at sentencing. Karadzic's appeal against the decision was dismissed in April.

In May, Karadzic challenged the tribunal's jurisdiction before the trial chamber, asking the judges to rule that the alleged immunity deal meant that it could not prosecute him. The trial chamber dismissed his challenge, reaffirming that any such agreement would be invalid under international law and would only be pertinent in sentencing when considering mitigating and aggravating factors. In any event, without any specific link to the United Nations Security Council or a prosecutorial order or direction, the alleged agreement is not material to Karadzic's defense. In October, the appeals chamber confirmed the trial chamber's ruling.

Karadzic has since written a letter to the current president of the United Nations Security Council asking for a resolution confirming his exemption from prosecution. In this context, it should be noted that the Security Council has passed a number of resolutions after the alleged agreement was concluded demanding Karadzic's arrest. Even if the Security Council were to pass a resolution purporting to protect Karadzic from the Yugoslav tribunal's jurisdiction, it would not affect the jurisdiction of other states to prosecute him for crimes under international law.

How is Karadzic handling his defense?

Karadzic has exercised his right to represent himself. He has objected to the assignment of stand-by counsel and amicus curiae (a lawyer assigned by the judges to assist the court), as both would be able to act contrary to his wishes. Karadzic's choice to forgo representation involves a number of consequences, including, as the appeals chamber in the Prosecutor v. Slobodan Milosevic described, giving up "many of the benefits associated with representation by counsel" and accepting responsibility "for the disadvantages this choice may bring."

His right to self-representation is not absolute, however. In Prosecutor v. Krajisnik, the appeals chamber has noted that when a defendant's lack of ability to conduct his own case significantly obstructs the proper and expeditious conduct of his trial, then the solution is the "restriction of his right to self-representation."

If Karadzic is representing himself, how is he managing such a complex case?

Karadzic, who is indigent, has selected a team of advisers who assist him in preparing his case. Since Karadzic is representing himself, he is not entitled to the full benefits of the tribunals' legal-aid provisions for indigent defendants, which includes financing for the legal counsel and support staff. But the court has ruled that defendants who represent themselves are nonetheless entitled to some degree of lesser financial support to facilitate the efficient administration and management of the case. This not intended to be public funding for expensive legal advice since a self-represented accused is supposed to fulfill all of the functions normally performed by legal counsel.

During the proceedings, Karadzic's legal advisor, Peter Robinson, is allowed to sit in the courtroom and can address the court if the judges grant permission to do so (based on a request by the defendant). Another legal advisor, Marko Sladojevic, and/or his case managers may also be present, but cannot address the court. Only two members of Karadzic's defense team may be in court at any given time.

Hasn't Karadzic threatened to boycott his trial? Can the trial still move forward?

Karadzic has notified the ICTY that he will not be appearing for the start of his trial on Monday, October 26, 2009. Karadzic contends that he has not been granted sufficient time and resources to prepare. He had requested a 10-month delay in the start the trial, which was denied.

At this writing, the court is still expected to hold proceedings on October 26. One question the judges may consider in light of Karadzic's refusal to appear is whether counsel may be imposed on him. The Appeals Chamber has established standards under which counsel may be imposed on defendants who choose to represent themselves. In the case of Slobodan Milosevic, the former Yugoslav leader, it was decided that the right to self-representation may only be curtailed "on the grounds that a defendant's self-representation is substantially and persistently obstructing the proper and expeditious conduct of his trial."

How will victims know about what is going on in The Hague?

With proceedings taking place hundreds of miles away from the affected communities in the region, the burden is on the Yugoslav tribunal to communicate important developments in the Karadzic trial to people in these areas. Over the last decade, the tribunal has developed a robust outreach and communications program to do precisely that, but this program is funded by voluntary contributions. Countries supportive of the tribunal's work should ensure that it has the funds it needs to maintain a strong outreach and communications program, to maximize the trial's impact in communities most affected by the crimes.

Are there lessons for the Karadzic trial from the tribunal's trial of Slobodan Milosevic?

Based on Human Rights Watch's research, we believe that the trial of the former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, who died in March 2006 before the tribunal finished the case, offers a number of valuable lessons for the Karadzic trial. For the prosecution, the Milosevic trial demonstrated why it is important to proceed with a streamlined indictment, which requires limiting the number of crime scenes included and selecting charges that are representative of the worst crimes as opposed to the entire range of crimes allegedly committed.

The prosecution has already trimmed Karadzic's indictment on several occasions, cutting the number of crime scenes needed to prove the counts, but the judges urged the prosecution to streamline it further, which the prosecution refused to do. The trial chamber, in response, instead limited the time the prosecution would have for its case: 300 hours for the examination and re-examination of all its witnesses, including those named on the reserve list (witnesses who are "on call" in the event there is some dispute over previously adjudicated facts).

The Milosevic trial and other cases since have also helped develop practices and jurisprudence that elaborate on how the right to self-representation can and should be curtailed if the effect of its exercise is to obstruct the achievement of a fair trial.

How long is the trial supposed to last?

The trial chamber has indicated that the whole case - including appeals - should be completed within 30 months and should not be extended, "even in the worst case scenario," beyond three years.

Isn't the tribunal supposed to be shutting its doors?

In mid-2003, the UN Security Council endorsed a completion strategy for the Yugoslav tribunal, calling for completion of investigations by the end of 2004, all trials by the end of 2008, and all remaining work, including appeals, by 2010. However, these dates have since been extended. Recently, the tribunal estimated that all but three trials will conclude in 2010, two more in early 2011, and that Karadzic's trial, the final trial to date, in early 2012. Most appeals are scheduled to be completed by the end of 2012, with a small number of cases anticipated to extend into the first half of 2013.

At the same time, given the unpredictable nature of trial activities (for instance, unexpected contempt proceedings and the health of defendants) it is impossible to state with certainty a precise timeline for the tribunal's completion. The desire to expedite proceedings to meet the completion strategy deadlines should not compromise the fairness and the effectiveness of the remaining trials.

What if Mladic is captured after the tribunal has completed its work?

Even after the tribunal closes its doors, a "residual mechanism" will be established to handle ongoing functions of the tribunal, which should include the trials of Mladic and Hadzic, if they are apprehended. In December 2008, the Security Council president has indicated that this structure should be "small, temporary and efficient," and the Security Council has put in place an informal working group to study and make recommendations about how to structure the residual mechanism, among other things. The challenge will be to ensure that the mechanism has the funds and expertise to execute the tribunal's core functions properly. Once established, an effective residual mechanism should send the signal to Mladic and Hadzic that they cannot simply "wait out" justice.

What about the others who are accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity in the former Yugoslavia?

The tribunal has made an important contribution to accountability in the former Yugoslavia, but by the end of its mandate, it will have tried only a relatively small number of cases, involving the more senior officials responsible and the most serious crimes. Many of those who pulled the trigger instead of giving the orders will only be brought to justice if they are tried in courts in the Western Balkans, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia. Although these "domestic" prosecutions are essential to close this gap, the justice systems in these countries have limited resources, which may compromise their ability to deliver fair and effective justice. While some specialist courts have received international assistance, additional support is needed across the justice system to tackle these challenges and promote fair trials in the region.

Updates on the status of Karadzic's self-representation before the Yugoslav tribunal proceedings

December 22, 2009:

The judges decided to begin the Karadzic trial without the accused in the dock. Doesn't that violate his right to a fair trial?

Karadzic's trial began before the Yugoslav tribunal on October 27, 2009. Karadzic refused to attend, contending he did not have adequate time to prepare his case, despite the trial and appeals chambers' rulings to the contrary. At the beginning of the proceedings, Presiding Judge O-Gon Kwon noted that, "Although the right of an accused person to be present during his trial is a fundamental one, it is well recognized that this right is not absolute." The judges had interpreted Karadzic's continued voluntary absence - despite a warning issued by the judges the previous day that the trial would start - as a waiver of his right to attend.

The judges therefore decided to move forward with the prosecution's opening statement. With this statement, the prosecution essentially sets out its theory of the case, but it is not considered evidence. The Registry was instructed to provide Karadzic and his legal advisers with a copy of the transcript and an audio recording of the hearing.

Karadzic also has a right to make an opening statement. Under Rule 84 of the tribunal's Rules of Procedure and Evidence, he can do so before the prosecution begins presenting evidence or at the end of the prosecution's case.

Given Karadzic's persistent refusal to attend, may the trial proceed?

On November 5, the judges decided that Karadzic's continued absence from the proceedings due to his claim that he was not prepared had "substantially and persistently obstructed the proper and expeditious conduct of his trial." The judges therefore decided to assign standby counsel to Karadzic and ordered a resumption of the trial for March 1, 2010 to give the standby counsel an opportunity to prepare. The decision to assign standby counsel followed a number of warnings to Karadzic that his decision to absent himself could result in imposing counsel and continuing the trial without him.

Does that mean that Karadzic has been stripped of his right to represent himself?

Not yet. In their November 5 decision, the judges reiterated that Karadzic will "continue to represent himself, including by dealing with the day-to-day matters that arise" and by further preparing for trial. The stand-by counsel will attend the proceedings, but will not take an active role in conducting Karadzic's defense. If, however, Karadzic refuses to attend the trial when it resumes on March 1 or engages in other obstructionist behavior, he will lose his right to represent himself. Moreover, he will lose the support of his defense team. Instead, the stand-by counsel will take over as his lawyer for the remainder of the trial.

February 26, 2010:

Did Karadzic select his counsel?

Karadzic was given the opportunity to select his lawyer. He was given a list of five defense lawyers who satisfied the requirements to practice before the tribunal, as outlined in Rule 44 of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence. He refused to make a selection, so the Registry assigned Richard Harvey, who has appeared as defense counsel before both this tribunal and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. Karadzic appealed that selection on the basis that he was not provided with the full list of eligible lawyers from which he could make a selection. On February 12, 2010, judges in the Appeal Chamber rejected Karadzic's argument, stating that the defendant must choose between self-representation and legal assistance of his choosing but that Karadzic is not entitled to both guarantees at the same time. The judges found that in drawing up a list of five attorneys, the Registrar followed fair procedures using reasonable criteria such as availability, willingness and previous experience at the Tribunal. The decision to appoint Richard Harvey as standby counsel therefore remains in effect.

Will Karadzic's trial resume on March 1? Isn't he seeking a postponement?

On February 18, the trial chamber judges decided that Karadzic "would not be prejudiced in any way" by giving his opening statement beginning on March 1, even if hearing evidence was postponed further. Karadzic has since confirmed in a written motion that he will present his opening statement on March 1, but is seeking to postpone the remainder of the trial until June, in part to review over 300,000 pages of documents the prosecution has disclosed since the beginning of the trial. The court has yet to rule on his motion.