The skewed logic of torturing, killing, and ‘disappearing’ people in the name of security only fuels Mali’s growing cycle of violence and abuse. The Malian and Burkinabe governments should rein in abusive units and prosecute those responsible.

Associate Africa Director, Human Rights Watch

In May and June, soldiers from Mali and Burkina Faso captured dozens of people… 17 members of my community have disappeared but people are terrified to talk about it. The behavior of both armies has strengthened the jihadist movement. Some young people have joined them after seeing their fathers tortured and brothers go missing.

The FAMA arrested me at the market where I was selling my wares – they didn’t tell me why. At their camp, they said, “We brought you here to kill you.” They took my money and my watch and over the next two hours we were kicked and beaten with batons and gun butts. They picked me up and slammed my head against a truck two times… two of my teeth came out, and two are now loose. I lost consciousness and blood was pouring from my mouth. They picked up the Burkinabe driver and beat his head against the ground… he was bad off. He’s in the hospital in Djibo [Burkina Faso].

They accused us of selling things to the jihadists. After being beaten, I heard the vroom vroom of a vehicle. They picked me up and held my head to the exhaust pipe of a big truck until my head was on fire. A soldier finally said, “Enough now, stop…. they could die.” Later, the soldiers took us to the gendarme post, but when they [gendarmes] mounted the truck and saw the state we were in – bleeding from the mouth, on the head, swollen, unable to walk – they got angry at the soldiers and refused to take us. The gendarmes and FAMA really yelled at each other… the gendarmes told the FAMA to take us to the hospital, which the soldiers did.

The soldiers found me near the well. They accused me of being with AQIM [Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb], asked for my gun and said, “Where are the jihadists?” They stole 143,000 CFA [US$260] and took me away with six others. It was a huge operation – they drove a while, then they put us in a hole on the road created by a land mine explosion earlier this year. They argued about whether or not to kill us there. “Should we kill them now?” said one. “Go grab the shovels,” said another. “No, they’ll find out in Bamako.” Some of our brothers are buried in common graves in Issèye and Yirima, so we were sure we would follow them.Later they put us into another hole – over a meter deep – near the Boni army checkpoint. In the hole were three other men, all blindfolded, bloody and swollen. They blindfolded us and bound our hands, and they made us, too, lie down in the burning sun as the abuse started. They beat us with iron bars, kicked us repeatedly and insulted our parents. It went on for hours… they spilled liquid on us, saying it was gasoline, that they would burn us alive. They didn’t even ask us questions, just accused us of being jihadists. We were desperately thirsty after hours in the sun, which in May is hotter than fire itself, but they refused.We went two days without eating and only got medical care once we reached Bamako. In total we spent 26 days in custody. Even now, months after the abuse, I’m still suffering… even yesterday I tried to work but I just couldn’t.

It happened at an army checkpoint a few kilometers from town. The soldiers were beating the man, who was around 35, then took paper, set it alight and burned his belly. About 30 minutes later, an officer arrived, asking angrily, “Why are you doing this?” The soldiers said they’d been tipped off that the man was selling weapons to the jihadists; that he had been found with a lot of cash. The man explained that he was an animal trader and had just sold some of his cows. The chief ordered the soldiers to stop the abuse and take him to the hospital for treatment.

...[the soldiers] put us into another hole... They blindfolded us and bound our hands... They beat us with iron bars, kicked us repeatedly and insulted our parents. It went on for hours… they spilled liquid on us, saying it was gasoline, that they would burn us alive. They didn’t even ask us questions, just accused us of being jihadists.

At 6 p.m., the army brought five men they had detained to the gendarmerie in Sévaré. They were in bad shape and really suffering; their faces were swollen; they were bleeding. The eldest of them couldn’t move and had to be carried into the cell. A few hours later, I heard people saying, “Give him water, he needs to drink, hurry...” But he couldn’t… he was dying. He was carried out of the cell at night… We learned from nurses that he died in hospital a few hours later. They said his body was covered with marks.

Human Rights Watch documented one case of severe mistreatment by government gendarmes. In late March 2017, gendarmes in Sévaré allegedly beat seven men from a village near Djenné, including a Quranic teacher. “During the night, a few of the gendarmes came into our cell and kicked and beat us. One man broke a few ribs and two others bled from their noses,” one detainee said.

Summary Executions and Common Graves

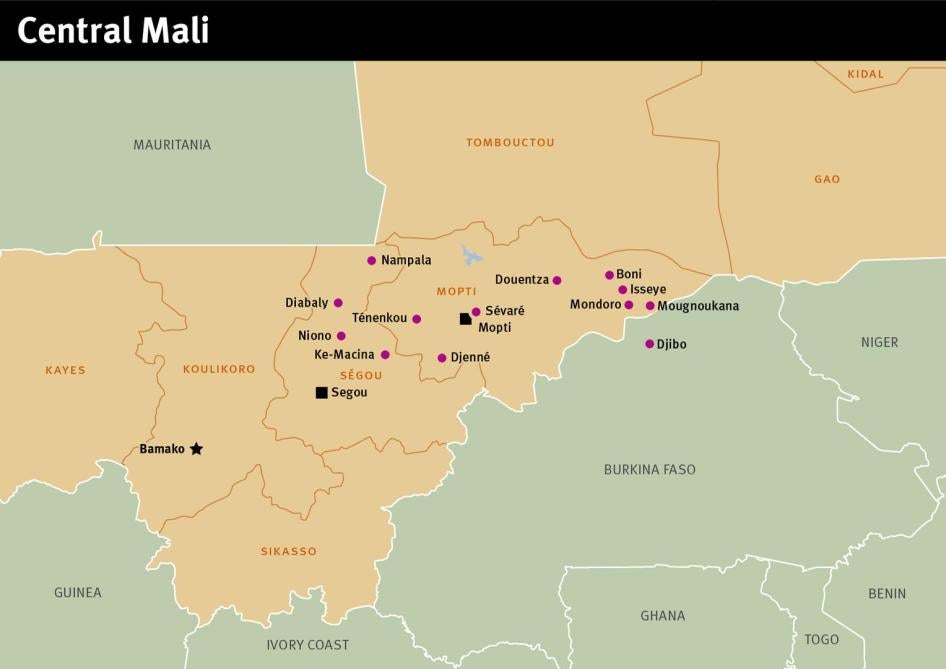

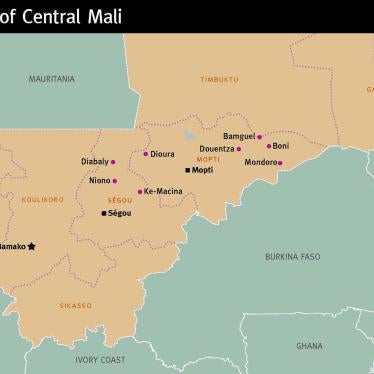

Human Rights Watch documented the existence of three common graves which witnesses and family members allege contain the remains of at least 14 men killed shortly after they were taken into custody by the Malian security services between late December 2016 and May 2017. All three are located within the Mondoro or Koro administrative areas in Mopti region, near Mali’s border with Burkina Faso.

“We all know about the common graves near Mondoro, but no one has filed a judicial complaint,” one witness said. “People are terrified to open their mouths – we’re all just trying to avoid further abuses.”

In August, community leaders gave Human Rights Watch photographs of what they believed to be a common grave about seven kilometers south of Mondoro, containing the remains of at least six of 17 men who went missing following their arrest by soldiers between May 2 and 9. A local businessperson said:

Around 11 a.m., I was in the bush when I heard the sound of gunfire. I saw three or four army vehicles about 200 to 300 meters away, off the main road. I felt something wasn’t right and crouched down. … I heard a second wave of gunfire. I stayed hidden for 15 minutes, until they left towards Mondoro on the main road. Later, I went there and saw a mound of dirt… like a newly dug grave, and the tire tracks. Things are tense in our zone. I am very frightened.

Two other common graves previously reported on by Human Rights Watch have yet to be investigated by the Malian authorities. The first, according to four witnesses from Yirima, allegedly contains three members of an extended family detained by soldiers on January 21 and later executed. One witness said:

The soldiers bound their eyes and drove off toward Mondoro [26 kilometers away]. Some minutes later we heard gunshots in the distance. We followed the vehicle tracks to Bamguel village, 18 kilometers away, and saw a grave there, newly dug, covered with branches of trees and many spent casings… We removed the earth and found our people there. I returned to our village to deliver the bad news.

The second grave allegedly contains five men from Issèye village detained and executed by soldiers on December 19, 2016. One of two witnesses said:

At about 11 a.m., 10 FAMA vehicles full of heavily armed soldiers stormed the village. They didn’t stay long. They detained the village chief first, then the others. Around 4 p.m., we heard gunfire, and the next morning we found the shallow grave just a few kilometers away. We uncovered the bodies… the chief was on top… each had several gunshot wounds.

Enforced Disappearances

Witnesses and family members described the enforced disappearance of 27 men, all of whom were last seen in the custody of Malian security forces. The men were detained from June 2016 through June 2017 during military operations in Mopti and Ségou regions. Family members said the government has provided no information on the fate or whereabouts of those detained, although some families have obtained information through informal sources.

Witnesses and family members provided information to Human Rights Watch suggesting that at least nine of these men were executed by the security services in the days after their detention. Other family members alleged that they had information that several others were being held in extrajudicial detention within the General Directorate of State Security (DGSE).

Human Rights Watch was given a list of 17 men from the villages of Mougnoukana, Douna, Kobou, Yangassadio, and Guedouware who have been “disappeared” since their arrest in early May. Several witnesses told Human Rights Watch that they had been arrested on May 2 with seven of the missing men.

“We’ve looked everywhere,” said a relative of several of the disappeared from Mondoro. “We asked the National Guard, FAMA and gendarmes, but our people are nowhere.”

Other cases of enforced disappearance in central Mali documented by Human Rights Watch include:

- Samba Diallo dit Samba Niger, 67, a herder from Dogo (Mopti region), was detained by the security forces while waiting for a bus in the town of Mopti around June 8, 2016. Family members believe he was being detained at the DGSE.

- Hassan Sidibe, 53; Boubacar Sidibe, 49; Boubacar Sidibe, 30; and Yonousa Sidibe, 30, were detained during an army operation in Tomoyi village, near the town of Ténenkou on January 17, 2017. Family members learned that they were being held in the DGSE.

- Boura Alou Diallo, 32, arrested by soldiers near the village of Kokoli around January 23, 2017, was last seen tied to a tree near the Mondoro army camp. Family members believe he was executed in late January.

- Hamidou Barry and Hamadoun Dambou, both about 25 and from Karena village, were arrested in January 2017 by gendarmes from a hospital in Douentza, where the former was being treated. The family believe they are being held in the DGSE.

- Ibrahim Barry, 35, was last seen on February 3, 2017, after being detained by gendarmes based in Sévaré during a meeting in Mopti organized by a local nongovernmental organization. Family members said they believe Barry had been beaten to death in custody.

- Sidi Koita, 34, was last seen on May 31 or June 1, 2017, being questioned by soldiers at a checkpoint a kilometer from the town of Nampala. Witnesses said he was questioned in relation to an ambush near Nampala the previous day in which several soldiers had died. Community members believe Koita was executed.

General Directorate of State Security

Human Rights Watch spoke with 24 former detainees who said they had been held in a detention center run by the DGSE for periods ranging from 27 days to five months. The men did not have access to family members or lawyers and were not permitted to make phone calls. They said they were not brought before a judge prior to or during their detention there.

A DGSE officer told Human Rights Watch that every person they detained had appeared before a judge and was under an arrest warrant. These claims were also contradicted by several lawyers, human rights advocates, and a judge, who told Human Rights Watch they knew several men detained by the DGSE who were being held extrajudicially.

All those interviewed said that they were regularly fed, received periodic medical check-ups, and had cells with fans or air conditioning. However, they complained of cramped sleeping conditions, and several said they lacked access to proper hygiene. One former detainee described being mistreated within the DSGE center.

Another former detainee, held in the DSGE center for 37 days between May and July, said:

There were 13 of us in my cell and eight in another cell. We were brought straight here from our villages. We ate okay and only one of us was slapped around a bit, but the weird part is that they only interrogated us once or at most two times. We don’t understand the law, but I know we didn’t see a judge until we were transferred from the DGSE to the gendarmerie five weeks later.

An elderly man held for over four months told Human Rights Watch:

There were 16 of us in the small cell. The entire time, none of us there had contact with our families. All that time… no sunlight – you don’t know if it’s night or day. I was only interrogated three times, at the beginning. The day I was freed, they put a black bag over my head, put me in a civilian car, drove several miles and told me to get out. I never signed any papers, never saw a judge… like it never happened. The day I walked back into my village… you should have seen their faces… they were convinced I was dead.

Burkina Faso Security Force Violations

Several witnesses from hamlets near Mali’s border with Burkina Faso described how, on June 9, Burkinabe soldiers detained about 74 men, ages 20 to 70. The soldiers accused the villagers of supporting the Burkina Faso Islamist armed group Ansaroul Islam, which also has bases in Mali.

Many of the men were severely beaten, and two detainees died from the mistreatment shortly after arriving in Djibo, Burkina Faso, witnesses said. They also alleged that the Burkinabe soldiers burned property during the operation.

One witness said: “The Burkina army received intel about a few [armed] Islamists in the area – several may have fled here after the big French operation in Foulsaré forest, further north – but they [the Burkinabe army] picked up every man they came across, whether farming, grazing their cows, or at home.”

Witnesses and community leaders said 44 men were taken to Burkina Faso for questioning and that seven still remained in detention there.

Several family members said neither the Burkinabe nor Malian authorities have informed them of the legal status of the detainees. “How can a foreign army come here, to Malian soil, and detain, beat, kill and imprison our people?” said one elder. “I just spoke with the father of a man killed. No one has called him to say his son is there. Should he have to go to Burkina himself and get his son’s body?”

While Burkinabe security forces are authorized to conduct cross-border operations, they are not, according to Malian Justice Ministry officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch, authorized to detain and question Malian residents in Burkina Faso. “The Burkina authorities do not have the authority to take people across our border for interrogation,” said a high-level official. “This would be arranged through a process of transfer or extradition.”

A 25-year-old farmer from the town of Kobou, seven kilometers from the Burkina Faso border, described what happened on June 9:

At about 9 a.m. I was in my field when I saw many vehicles full of soldiers. They were aggressive and started to beat me in my field, hitting me with their guns and a belt. They threw me in their vehicle with the others and took us to Dolga hamlet a few kilometers away. “Why are you working with the jihadists who kill us?” they screamed. They beat us there as well, but the terrible beatings happened at the moment of our arrest. Their medic stitched a few of us up. I was among the 30 who were freed the same day… but they took over 40 away to Burkina.

A 57-year-old farmer from Kobou village described the apparent death of a man named Bourema Hama Diallo:

They started whacking me on my back with belts from the moment they showed up at my farm. They threw me in the truck… it was a huge operation… when we got to Dolga I found nearly the whole male population there. Many were injured; Bourema among them – he’d been hit on his head and was bleeding a lot. He almost passed out before they put us in trucks and took us to Djibo, some to the police and some to the gendarmerie. I was one of 18 in a truck that went to the gendarmerie.

After arriving, they took off my blindfold and I saw that he [Bourema] was bad off. Seeing this the gendarmes said, “We need to take him to the clinic.” They had to carry him. I know he died because later that night the gendarme who guarded us said, “Two of your people died before arriving at the health center.” The second [man] wasn’t in my truck. I didn’t see the bodies after that, but I know Bourema’s father, and he has yet to see his son.