Since the 1991 Tuareg rebellion and proliferation of AK-47s [assault rifles], banditry – of our animals, money and motorcycles – has been rampant. Honestly, since the jihadists [Islamists] started circulating in our zone, the security situation has drastically improved.

A Peuhl chief said the Islamists were exploiting both Peuhl-Tuareg communal tensions and longstanding anger with the central government to recruit young men in central Mali:

The politics of the jihadist is to provide a better alternative to the state. Our people don’t associate the state with security and services, but rather with predatory behavior and negligence. Since 1991, we have complained about banditry, but nothing has been done. In 2015, the presence of jihadists has grown; people are joining them as a result of their ability to protect us, our animals, and our possessions, especially from Tuareg bandits. There is no justice – our cows are stolen, our people are killed… the jihadists are the response.

In contrast, Dogon leaders said the Islamists operating in areas near the border with Burkina Faso were abusive, engaged in frequent criminality, and were exploiting communal tensions between them and the Malian Peuhl over land and grazing.

“Sure, there’s tension as the Peuhl moved their cows through our lands, but we used to sit down, talk it through and find a solution,” said a Dogon businessman. “But now, some Peuhl come with AK-47s and want to kill us. It was never like this before.”

The Dogon complained bitterly about regular acts of banditry targeting their community. “Honestly, Islamist, bandit, we can’t tell the difference,” said one Dogon villager. Another noted, “At times, these people act like criminals, not as proper Muslims – they steal using the excuse that the money was gotten through corruption or is from a Western organization. The banditry is getting worse and worse in our area.”

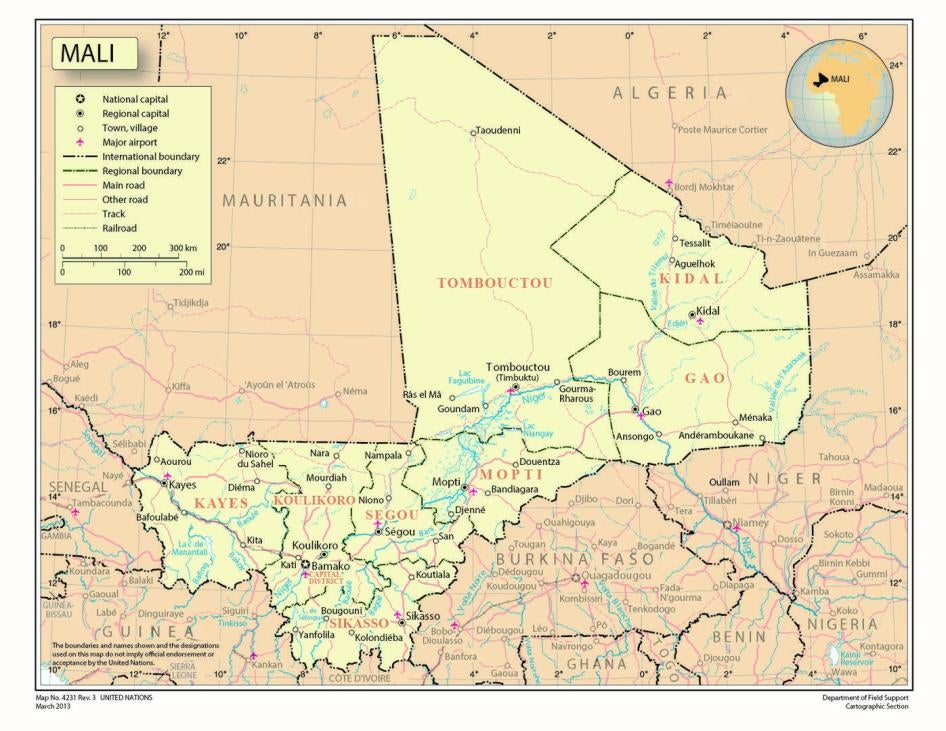

Killings by Islamist Armed Groups in Central and Southern Mali

Witnesses said that those responsible for the execution-style killing of 19 civilians during 2015 belonged to Islamist armed groups. Witnesses, family members, and community leaders said the majority were executed for alleged collaboration with the security forces.

Attacks by Islamist armed groups in Bamako and Sévaré left an additional 29 civilians dead, at least 25 of whom had been deliberately targeted. Five were killed during the March 7 attack on the La Terrasse nightclub in Bamako. Another five, including four UN contractors, were killed during the August 7 and 8 attack and Byblos hotel siege in Sévaré. The heaviest toll from a single attack, was the19 civilians killed during the November 20 attack on the Radisson Blu hotel in Bamako. AQIM, Al-Mourabitoun and the FLM took responsibility for one or more of these and several other smaller attacks in 2015.

A villager from Isseyé, 85 kilometers from Douentza, described the December 23 capture of Boura Issa Ongoiba, a local official:

At about 5 p.m., we were in front of Boura Issa’s shop. I saw three motorcycles coming toward us, each with two heavily armed men – one even had a rocket launcher. They shot in the air, and yelled in Peuhl for us to move back; they addressed Boura Issa directly, ordering him to come with them. As they left, they threatened us in Bambara, “No one should get up until we’re gone.” In the third night after his disappearance, they came, discreetly, and deposited the decapitated head of Boura Issa Ongoiba in front of his store. They left without saying a word.

Another neighbor said the family buried Issa’s head and “went in search of his body, which was found four kilometers away.”

Other witnesses described Islamists fighters’ December 16 execution of a municipal council member near Karena village in the Mopti region, and the August 13 killing of Al Hadji Sekou Bah, an imam from Barkerou village, in the Ségou region, for allegedly providing information that had led to the arrest and enforced disappearance by Malian soldiers a few weeks earlier of a village man accused of membership in the FLM. “Two armed men ordered him at gunpoint to walk some 50 meters to the mosque, then five minutes later we heard gunshots, and calls of ‘Allah hu Akbar’ [‘God is great’]. We found him with a bullet in the head and one in the chest,” a family member said.

A local official described how on the December 17, Islamists executed Alhadji Toure, a municipal council member from Tougué Mourrari, 60 kilometers north of Djenne, and returned a day later to burn the home of the local school director.

Four witnesses described the October 9 execution of Timote Kodio, the deputy mayor of Douna-Pen village, about 30 kilometers from the border with Burkina Faso. Two said they heard the attackers accuse Kodio of providing information about the Islamists’ whereabouts to the Malian military. “They dragged him out from him his room and murdered him in front of his entire family,” one said. A third witness said:

Six of them arrived on three motorcycles, firing as they arrived, faces covered in turbans and with some camouflage [clothing] on. They were armed with AKs; two had RPGs [rocket propelled grenades] and spoke Pulaar and Dogon. An old man took off running, but they threatened to kill him and ordered all of us not to move. Meanwhile the other four went inside Kodio’s house. They asked everyone in the house to lie down, then shot Kodio point-blank at least three times. Immediately after the shots, one of them made a phone call – in front of us – as if to tell their boss the deed was done.

Community leaders and villagers said abuses by Islamist armed groups often were underscored by long-standing communal tensions, usually between sedentary and pastoral communities, or motivated by interpersonal grievances or criminal intent.

One Dogon leader from Mopti region said, “Yes, the jihadists are in our zone, but the situation is very complex: an Islamist can also be a bandit, and a bandit a jihadist.” A Peuhl leader said: “These cases may be score settling, banditry, jihadist business, or likely a combination of all of three.”

Peuhl and Dogon community leaders described a lethal incident near Niangassadiou, a village in the Mopti region, about 15 kilometers from the Burkina Faso border, after a communal dispute over grazing. Local residents said that armed Islamists, most of whom were Nigerien Peuhls who had been associated with MUJAO in 2012, killed six Dogon residents in three hamlets on July 18, the Muslim holiday of Eid al Fitr (Tabaski). A witness to two of the killings said:

Tension was high after the Peuhl grazed their cows in a field where the grain was just breaking through the soil. The Dogon got angry and killed a few of their animals; the Peuhl said the Dogon had planted their crops in the middle of a grazing route so it was their fault.

As I reached my village I saw four motorcycles with armed men, dressed in the beige boubous worn by the Niger Peuhl– their turbans are tied in a distinct way. All had long guns—AKs—one had a string of bullets almost dragging in the sand. I hid, immediately, but heard them order everyone to the ground, face down, then I heard several gunshots. About 20 minutes later, I saw the armed men leaving – some carrying clothing, food they’d looted. I ran to the village. Women were crying, I saw my relative, dead, and another man lay wounded, but gravely. He died minutes later. They went on to kill four others in two nearby farms. We used to talk through these problems, but this time, it turned so violent.

Rape by Islamist Armed Fighters

A group of five Islamist fighters raped four women in an isolated farmhouse between Bandiagara and Sévaré on August 6, 2015. Three of the victims and a woman who provided medical care described the attack. The victims said that the fighters held the women captive overnight. A 25-year-old victim said:

On our way from Bandiagara, armed men emerged from the bush, and forced us to stop. They were dressed in traditional Peuhl dress. All five were armed and two had big backpacks. It’s very isolated there. They forced us onto a smaller road, then two drove off on my motorcycle. Two others then forced us into the bush where they raped us – one each, and one time each. Then, around dusk, they ordered us to walk to a house some distance away – it was terrifying; I thought they were going to leave us dead in the bush.

In that house were two older women, widows, whom they also raped. After raping us, they forced all of us to wash, pray and say “Allah hu akbar.” Then they made the women who were desperately poor kill and cook their only sheep. They didn’t tie us, but they had guns and had taken our phones. They said, “No one leaves; no one enters.” We were all inside, enclosed in the same room… they talked all night, and kept saying “Allah hu akbar.” They left about 4 a.m. A few hours later we started hearing about the big attack on Sévaré.

Threats and Intimidation by Islamist Armed Groups

Several villagers from hamlets around Karena village, about 30 kilometers from Douentza, described being terrified by the presence of armed Islamist fighters who had, since September, passed regularly through their area. One resident who had since fled said:

In October, 12 of the armed men on motorbikes violently broke up a wedding ceremony in our village. They fired in the air; people started running; some women were so frightened they fled without their children. All the animals took off running; it took three days to gather them up. The men said it is haram [forbidden] to have women and men together at a wedding. Some days later, nine of them returned on five bikes; they found Samba Oumar, a Quranic student, on his way back from his farm and beat him severely. Many teachers and local officials have fled. Honestly, we’re so afraid; we don’t know what they want.

Villagers from a hamlet near Yogodogi village, about 40 kilometers from the Burkina Faso border, said that in late September a group of heavily armed Islamist fighters attacked, beat and threatened several men they accused of working for a humanitarian organization supported by a Western government. When they returned several days later, they killed a local herder. One villager said:

Eight of them came the first time. They tied up three people from an NGO (local nongovernmental organization) then beat them badly, until they bled. They brought out a knife saying they’d slit their throats. They ranted against the West, saying “taking money from whites to give to Muslims is haram. We are combatants of Jihad; if you are not Muslim, we will kill you.” This NGO gives aid to children and women. But they said it was for whites and not allowed in their zone. They stole three motorcycles and lots of money. Some days later they attacked a local official – I think they were trying to kill him – but instead, they killed his berger [herdsman]; I saw the body after the army had chased the Islamists away. We buried him in Bagil Hama – people there said they’d seen the jihadists that day and said it was the same people who attacked Niangassadiou.

They stayed for about two hours. I believe by the clothes they wore, by the way they spoke Pulaar, that all were from Niger. Each one had a rifle; they were dressed in beige boubous, and several had vests with pockets filled with bullet cartridges.

A Bamako-based Peuhl community leader working with a Pulaar radio station said he received threatening phone calls in September from Islamists based in Mopti region: “They ordered me to cease playing music and theater on my radio; they told me to fear God if I didn’t heed their warning. The one talking said he was with the group of Quranic students from Mopti Cercle. He ranted and yelled, saying if I continue, he will destroy the radio and hunt me down in Bamako; that music and theater were haram.”

A Peuhl herder who attended a meeting in a village near Tenenkou said that armed Islamists threatened to kill the family members of any Peuhl youth who joined the army. “The jihadists got word that people in Bamako are thinking of integrating the Peuhl into the army as a way of dealing with the problem in central Mali. Some of us want to enter, but a few months ago, the jihadists called a meeting and told us, ‘Go ahead and go; but the day you return, you’ll find your father has been killed.’”

A villager from Kewa village, 56 kilometers from Djenne, described a note left by the armed Islamists in early January 2016: “We woke up to find a note nailed to the wall of the mosque. The date was in French, and the rest was in Arabic. People who read Arabic said it ordered us not to trust MINUSMA, the French and Westerners. Many people are afraid after they killed a local villager in September.”

Mistreatment of Detainees by Malian Security Forces

Human Rights Watch interviewed 74 men who had been detained by the Malian security forces in 2015 for their suspected support of or membership in Islamist groups in central and southern Mali; nearly all had been arrested by military personnel. The vast majority were ethnic Peuhl and some were Dogon.

Many said they had been accused of selling milk, gas, sugar, cooking oil, meat, or motorcycles to an Islamist armed group, of providing intelligence, or of having a relative in an Islamist group.

Local human rights groups and community leaders told Human Rights Watch they believed the evidentiary basis for many of the detentions was weak, and sometimes based on false intelligence provided by people to settle personal scores.

A Peuhl community leader said that, “After a soldier or gendarme is killed they [the security forces] go crazy, detaining a dozen people here or there who have nothing to do with the FLM.” A lawyer said that “so many of the so-called Islamists are older men in their fifties, sixties and even seventies; not exactly the profile of a jihadist!”

Another lawyer familiar with many of the cases said:

Many of these dossiers are not holding up; isn’t this the definition of arbitrary? As soon as they are reviewed by the judge, they are let go on the basis of no evidence. It’s a terrible humiliation for these men; many are tied like a sheep in front of their community, beaten, deprived of liberty for weeks, only to be let go by the judge for lack of evidence, then return home sick, or nursing wounds from the mistreatment. This kind of behavior is driving people to the jihadists.

While the abuse did not appear to be systematic, about half of the detainees interviewed said they had suffered serious mistreatment. In all but a few cases, the abuse was meted out by army soldiers during ad hoc interrogations in the first few days after detention, though Malian soldiers are not authorized to interrogate detainees. The abuse took place in army bases, bush camps and at checkpoints. In several cases officers, including a captain and a commander, were present during the abuse. The most serious cases Human Rights Watch documented occurred during the first six months of 2015 and by soldiers based in Nampala and Diabaly.

The detainees, many of whom had scars and showed visible signs of torture, described being hogtied and at times suspended for long periods of time; bound at the wrists and ankles with cords or wire that cut through their flesh; pummeled with fists and gun butts; kicked; enclosed in army vehicles and rooms without ventilation for hours at a time; suspended from trees; burned; urinated upon; and threatened with death or subjected to mock execution. They were also routinely denied food, water, and medical care.

Many said that soldiers bound their hands and feet: with rubber, plastic, or wire cord, severely restricting their circulation, in many cases cutting the flesh or leaving long-lasting scars. Many were also hogtied. Human Right Watch has documented this abusive form of restraint in Mali since 2012.

Human Rights Watch observed the right hand of a 45-year-old farmer detained by soldiers in late October in his village, 100 kilometers from Bankass. His hand was split open from the area between the thumb and index finger down to the wrist from what he described as swelling provoked by being hogtied and hung with a large rock on his back from 11 a.m. until 5 p.m. At night he was subjected to a mock execution.

In another case, a herder, 55, was hogtied and suspended for several hours with a rock on his back in April. The man said, “I lost feeling for over two months; I couldn’t go to the bathroom, feed myself or hold a cup of tea. I bled so much. It still hurts and you can see the scars for yourself.”

A 60-year-old man accused of selling to milk to the Islamists said his arm was broken after he was hogtied and driven over bad roads for over 12 hours in November. Cuts on both wrists were clearly visible and his arm appeared deformed.

A Peuhl doctor who had treated many detainees said, “Many of the detainees I cared for had lost sensation in their arms for days, weeks, and in a few cases, months. One man needed 20 sessions of physical therapy, and many still can’t work. The impact of this on their lives and livelihoods is really serious.”

Six men described being subjected to mock executions, while several others said soldiers brandishing knives threatened to slit their throats. “They took me to a bush camp and accused me of giving information to the jihadists,” said a 40-year-old herder detained by soldiers in October near the border with Burkina Faso. “During the questioning, they walked behind me and fired a gun, close to my ear.” Witnesses said that another man, detained in November, was doused with gasoline and threatened with being set alight.

Torture in Nampala and Diabaly Military Camps

Human Rights Watch documented numerous cases of torture at the Nampala military camp in Ségou region. Human Rights Watch interviewed 26 detainees who said they had suffered torture and other ill-treatment, and were witnesses to other cases of severe mistreatment in military camps. Most of these cases occurred in the first half of 2015. A 60-year-old shepherd detained in April said he lost several teeth and bled profusely during his interrogation in Nampala:

They tied me and hung me upside down from 2 a.m. to 5 a.m. They asked where the jihadists were; I said I only care about my animals. Then a soldier thrust his gun into my face with force. I lost half my teeth. There was so much blood in my mouth, I vomited, and my wrists bled because of the cord. I was let go by the judge for lack of proof. Are the soldiers there to protect or terrorize us?

Some minutes later, it was my turn. They kicked my feet out from under me, tied my feet and hands with rubber cord, then pushed an iron bar through the cord ties, and hung me like an animal inside the corridor. “Do you know the jihadists who attacked Nampala? Tell us!” [they said]. They lit a fire that reached to about one foot from my boubou. They put wood and paper to feed the fire. Later one of them burned my foot. After 15 minutes, they took me down and it was [name withheld’s] turn.

The soldiers came for me at 11 p.m. After stringing me up, they put a brick on my back and left me like that. Two soldiers started asking questions: “Who attacked Nampala? Tell us and we’ll free you.” I told them I don’t know anything about it. One said, “If you don’t tell us, you’ll die like three of your relatives, tied right there as you are.” They left me for at least three hours until I lost consciousness. After being dragged back to the cell, I found seven herders —all Peuhl and one Bella—from villages around Nampala. One of them, an old man, couldn’t lift his arm. Three had traces of beatings on their backs. Another two were bleeding, on the wrists and feet. Then my brother was brought in, bleeding. After several weeks in detention, the procurer [prosecutor] liberated all eight of us at the end of May.

A farmer, 46, accused of hiding arms described being tortured in the presence of an army officer in the Diabaly military camp in April:

They tied me, then locked me up for hours in an armored car, parked in the sun. I couldn’t breathe and felt on fire from the heat. During interrogation, they put a gun and Quran in front of me, asking, “Do you know these things? Where are the guns?” They fired behind my back one time and said, “If you don’t tell us where the jihadists are, you will die.” An officer said, “I’m in charge here, and if this method isn’t sufficient, we’ll try something else.” They stripped me to my underwear, then hung me upside down from a tree for over an hour, beating and questioning me all the while. “All you Peuhl are in touch with them” [they said]. I lost consciousness, and woke up inside the armored car.

Later, one soldier put a knife to my neck, cutting it slightly, but another stopped him. Then I was punched in the face. Like that, I was interrogated five times. I bled on my back, and from my eye. It only stopped after reaching the gendarmerie in Niono, where I saw several other men who had also been beaten by the FAMA; one so badly he couldn’t move. The gendarmes took us to the clinic. After seeing the judge, he let most of us go, saying our dossiers were empty. The soldiers are incapable of finding the jihadists who are harming us, so they go after us.

A shepherd, 47, described being tortured after he was stopped at a checkpoint in June. The torture continued after he was taken to the Nampala military base:

I was arrested on market day when I’d gone to buy grain for my cows. A soldier asked for me, like he had my name, and ordered me into his vehicle. When we reached a checkpoint, he hogtied me with a rubber cord; I was face down, legs behind. They took off my boubou, and they began beating me with a switch. They put the switch in the fire and burned me over and over again – on my head, my back… they kept going back and forth to the fire and passing it over my body. They kicked and hit me in the face. They accused me of selling the jihadists meat and gas, and of informing on the FAMA. “You bastard, where are they hiding?” [they said]. They urinated on me… I was wet with blood. They also kicked me, put sand in my mouth. It lasted from 4:30 to 6:30 p.m.

Later, I was dragged to the Nampala base, where I was interrogated by the officer in charge and others. They said they would kill me that night. The next morning I was taken to the clinic, but the officer yelled for the nurse to stop, and ordered me back to the cell. Later, I was taken out for interrogation again, but a soldier intervened, saying, “He’s almost dead anyway.” I couldn’t stand, and insisted that, kill me or not, I was innocent. I spent 11 days in Nampala during which one hand was chained to a motorcycle in the cell. I received no medical care. My body was swollen. I could barely sleep and was in terrible pain.

Some days later I was seen by a judge, and that very day liberated with three others; all had been tortured. I was later treated for second degree burns. Now it hurts when I walk; my skin is so tight. When my wife saw me she cried.

Enforced Disappearance

Residents of Barkerou village in the Ségou region said that soldiers arrested Amadou Djadie, a 47-year-old herder, in late July. He is still missing. A witness said:

From my house, I saw clearly as the soldiers went to [Djadie’s] house, dragged him to a military vehicle and took him away. They asked villagers if he was a rebel, and why he had recently come from Mauritania. They took him toward Nampala [the military base]. Since that time no one has seen him, and honestly, people are terrified to bring it up.

A family member said they had looked for him in several detention centers and believe he was killed in custody.

A well-informed member of the security forces said he had been told that soldiers had taken Djadie from the base, told him to run, and then gunned him down.

Role of Gendarmes

As has been the case since 2012, the vast majority of detainees said the abuse stopped after they were handed over to government gendarmes. Several torture victims described heated discussions when gendarmes observed the signs of abuse or torture. One said: “When the gendarme saw our open wounds, that we could barely walk, he screamed at the soldiers, ‘Look at what you’ve done to these people! You have no right to do this, rebel or not. Is this normal? Were you not trained?’”

Several victims said they were taken for medical treatment to a local clinic, and that gendarmes insisted that medical certificates of their injuries received while in army custody be included in their legal dossiers.

Human Rights Watched documented fewer cases of mistreatment when people were arrested by soldiers accompanied by gendarmes who have the mandated role of provost marshal. When asked why gendarmes are not always present in military operations, a Defense Ministry official told Human Right Watch: “They can’t be everywhere, and the mistreatment often happens in isolated places.”

Defense Ministry Response to Allegations of Abuse

Human Rights Watch met with Colonel-Major Seidine Oumar Dicko, from the Ministry of Defense, on December 12 to share findings about alleged abuse by Malian military personnel. He said that “ensuring respect of detainees is in no uncertain terms a priority of the Ministry of Defense. We fully recognize that army soldiers do not have the right to mistreat detainees; nor do they have the mandate to interrogate.”

Colonel Dicko said that compared with past years, “there have been significant signs of improvement demonstrated in consistent training in international humanitarian law, and clear instructions given before military operations to ensure the rights of detainees are respected. …Things are changing slowly; it is all about training.”

He also said that allegations of abuse would be investigated. However, many of the serious alleged abuses by the security forces, including extrajudicial killings of civilians, documented by Human Rights Watch and other human rights organizations since 2012, have not been investigated. Thus far, none of the perpetrators have been held to account.

Human Rights Watch research suggests that while torture and ill-treatment remain a major problem in military custody, mistreatment appears to have declined. Interviews with scores of detained men accused of supporting armed groups in 2013 and 2014 found that virtually everyone taken into Malian military custody had been beaten, and many were tortured, as opposed to about half of the 74 interviewed in 2015.