(Milan) – Asylum seekers and other migrants arriving by sea to Spanish shores are held in poor conditions and face obstacles in applying for asylum. They are held for days in dark, dank cells in police stations and almost certainly will then automatically be placed in longer-term immigration detention facilities pending deportation that may never happen.

“Dark, cage-like police cells are no place to hold asylum seekers and migrants who reach Spain,” said Judith Sunderland, associate Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “Spain is violating migrants’ rights, and there is no evidence it serves as a deterrent to others.”

The number of asylum seekers and other migrants crossing the western Mediterranean to Spain is increasing. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), 7,847 people reached Spanish shores between January 1 and July 26, 2017, compared with 2,476 during the same period in 2016.

Although the numbers pale in comparison to the 94,445 people disembarked in Italy during the first seven months of 2017, Spanish interior minister Juan Ignacio Zoido cited “important pressure” on Spanish ports in rejecting Italy’s recent request to have some of the people rescued in the central Mediterranean taken to Spain.

Almost all adults and children traveling with a family member arriving to mainland Spain by boat are detained for up to 72 hours in police facilities for identification and processing. The majority of adult men and women are then sent to an immigration detention center for a maximum of 60 days, pending deportation. If they cannot be deported they are released but have no legal right to remain and are under obligation to leave the country.

Conditions in police facilities in Motril, Almería, and Málaga, which Human Rights Watch visited in May, are substandard, Human Rights Watch found. The facilities in Motril and Almería have large, poorly lit cells with thin mattresses on the floor, while Málaga police station has an underground jail with no natural light or ventilation.

In Motril, women and children are placed separately in the one cell with bunk beds. In Málaga and Motril, the cells have thick vertical bars while in Almeria, the cells are separated from the hallway by tightly woven steel grills. Detainees are locked inside at all times, and taken out only for medical checks, fingerprinting, interviews and, in Almería and Málaga, to go to the bathroom because there are none inside the cells. Although there are outside, enclosed spaces in Almería and Motril, immigration detainees are not allowed to use them. The Spanish Red Cross is present at all disembarkations to do basic medical screening and provide hygiene kits. Men are not provided toothbrushes on the grounds they may be used as weapons.

While unaccompanied children are generally transferred to dedicated centers, children traveling with family members are detained in Motril and Almería, according to authorities. An observer told Human Rights Watch he saw children playing in dirty water from overflowing toilets in the cells of the Motril port detention facility in April, when nine children were detained there with their mothers for three days. Police in Málaga told Human Rights Watch that children are placed with social services while their family members are detained in the basement of that city’s central police station.

Migrants detained told Human Rights Watch that they did not have individual meetings with a lawyer in police custody and were given little or no information about applying for asylum. Human Rights Watch has documented in the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla what appears to be a policy to discourage asylum applications. Despite a significant increase in asylum applications in Spain over the past few years, in 2016 the country received just 1.3 percent of all new applications filed in the 28 EU member states, and has a low per capita rate.

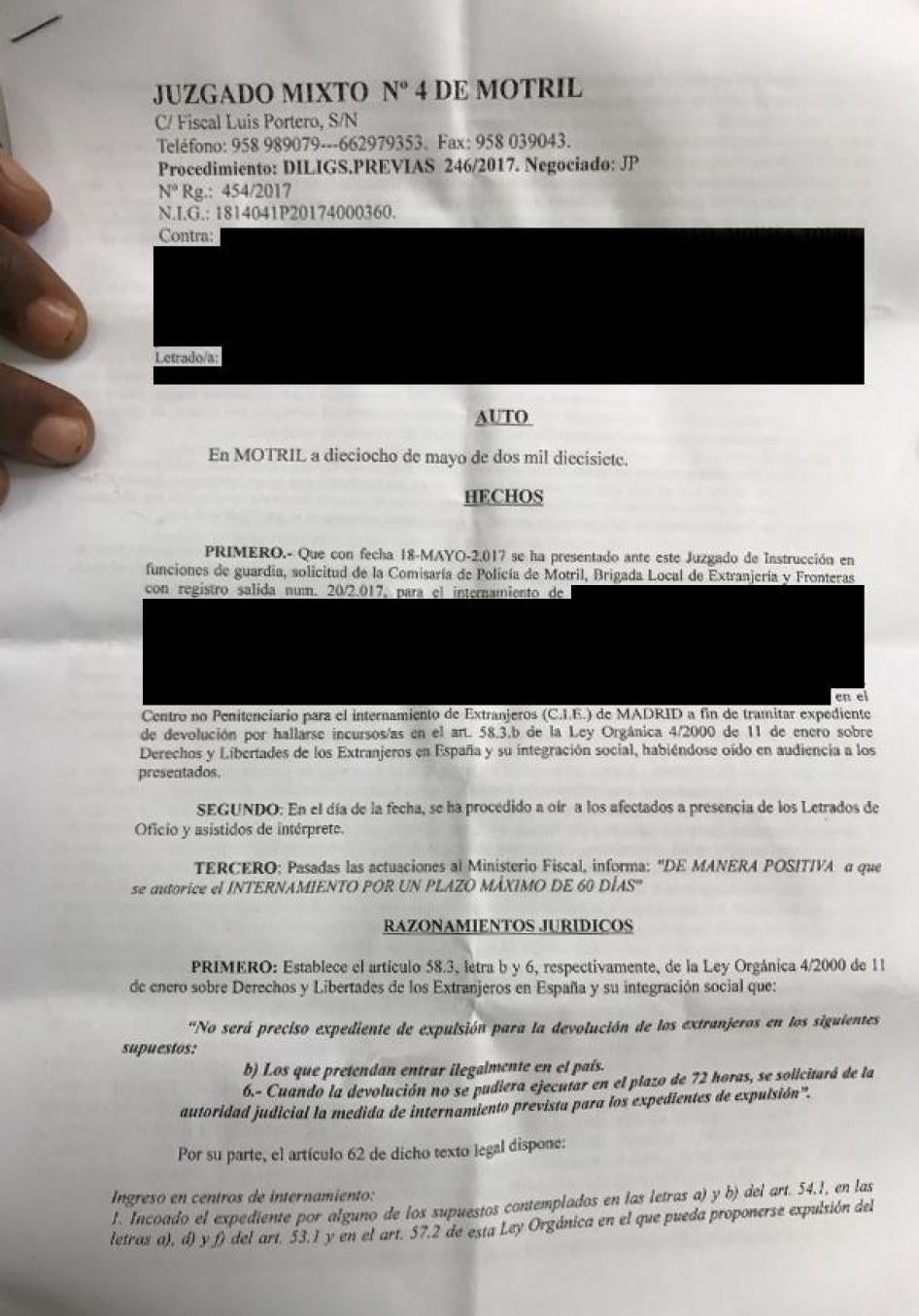

Within the permitted 72 hours of detention, the police must fingerprint and interview all migrants, issue a return order, and take the migrants before a judge to confirm or dismiss the order and to make a custody decision. At these hearings in Motril and Almería, judges routinely conduct group interviews, including via teleconferencing, asking detained migrants pro forma questions before sending virtually all adults to immigration detention pending deportation.

In Málaga, concerted advocacy by the local bar association has improved procedures and ensured individual interviews by the judge and individualized detention orders. Alvaro García España, a member of the Málaga bar association, said, however, that in Málaga, as elsewhere, detention orders were “systematic.”

Detention for the purpose of deportation should only be ordered where there is a likelihood that deportation can and will be carried out reasonably promptly, with due diligence. However, according to the Defensor del Pueblo, Spain’s human rights institute, only 29 percent of those detained in these facilities in 2016 were actually deported that year.

Alternatives to detention do exist, and should be used more effectively, Human Rights Watch said. Spanish law allows authorities to use non-custodial measures including withdrawal of documents, reporting requirements, and obligation to live in a certain place to ensure a person can be located to enforce a return or deportation order. Spain also has a system of “humanitarian shelters,” financed by the government and run by nongovernmental organizations, where undocumented migrants may stay for up to three months.

While a relatively short journey, the sea route in the western Mediterranean is deadly. The IOM estimates that 119 people have died at sea since the beginning of the year, with 49 people perishing in early July in a single incident.

Spanish authorities should take urgent steps to improve conditions in police port facilities for people arriving by sea and ensure that they have effective access to information and legal advice, Human Rights Watch said. Given the particularly poor conditions in the Málaga central police station, people who enter there should not be detained, even for a brief period. The authorities should find alternative places to hold them for initial processing. As long as the port facilities in Motril and Almería are used, new measures should be adopted to allow more freedom of movement within the compound, including use of outside spaces and free access to bathrooms. All detainees should be provided basic hygiene products, including toothbrushes. They should receive clear, consistent information about their rights – including their right to apply for asylum – in individual interviews with lawyers. Judges should assess individual circumstances, including the likelihood of deportation orders being executed promptly, before sending anyone to immigration detention and order alternatives to detention as much as possible.

“Whether by negligence or design, Spain fails to treat asylum seekers and migrants who arrive by sea with humanity and dignity, Sunderland said. “Spanish authorities should urgently upgrade police facilities and ensure full information, access to asylum, and proper judicial oversight for all migrants and asylum seekers who reach its shores.”

Between May 16 and 25, Human Rights Watch visited the immigration detention centers in Algeciras and Tarifa, the police port facilities in Motril and Almería, and the central police station in Málaga where people rescued at sea are held upon arrival. All are in Andalusia. The National Police gave Human Rights Watch permission to visit only the administrative and outside areas of the two detention centers and to speak with staff, but not to visit cells or speak with detainees. Human Rights Watch was allowed to inspect the port facilities in Motril and Almería, and authorities allowed private interviews with people held there who wished to be interviewed.

At the time of the visits, there were no children in the police facilities. In Málaga, Human Rights Watch briefly visited the cells, but no migrants or asylum seekers who had arrived by boat were detained there at the time. Human Rights Watch also interviewed men who had recently arrived by sea in two shelters operated by nongovernmental groups for undocumented migrants in El Ejido and Granada.

Human Rights Watch spoke with 19 men and two women, seven from Guinea, five each from Cameroon and Cote d’Ivoire, two from Liberia, and one each from Senegal and Mali. All names have been changed to protect people’s identity.

Western Mediterranean Boat Migration

Boat migration from North Africa to mainland Spain across the Strait of Gibraltar and the Alboran Sea is increasing. The International Organization for Migration recorded a 217 percent increase in the first seven months of 2017 compared with the same period in 2016, when more than 8,000 arrived throughout the year. Most boats leave the Moroccan coast at night, and can spend 24 hours or more in the water before being rescued by Salvamento Marítimo, the Spanish maritime rescue service, and disembarked at various Andalusian ports. People use inflatable rubber boats with side-board engines, but also so-called toy boats – small, inflatable rafts big enough for seven or eight people, without engines. Some wear life vests. Others who cannot afford them – like Emmanuel, an 18-year-old from Cote d’Ivoire – wear bike tires.

Adolfo Serrano, head of Salvamento Marítimo in Algeciras, said that Spain’s declared search-and-rescue zone extends all the way to the Moroccan coast. However, Spanish authorities rely on Morocco to patrol its coastline and intercept or rescue boats within Moroccan territorial waters. Salvamento Marítimo policy is to share any intelligence with their Moroccan counterparts and only intervene in Moroccan waters in case of imminent loss of life. Colonel Antonio Sierras, head of the Guardia Civil in Melilla, said that Spain takes the view that boats have entered Spanish territory only once inside the inner harbors of Ceuta and Melilla.

Migrants told Human Rights Watch that many take to the seas after repeated failed attempts to scale the fences surrounding Ceuta and Melilla. Marcel, 34, from Cameroon, tried six times to cross into Ceuta: “I never managed, just got beaten up [by Moroccan security forces], broken bones……once when I was already at the fence they beat me on the foot to make me fall off the fence. Another time they hit me with a baton; it felt like a knife.”

Interviews with sub-Saharan Africans in Ceuta and Melilla in March and in Andalusia in May indicate that violence by Moroccan border guards and other abuses previously documented by Human Rights Watch continue.

Conditions in Police Facilities

Migrants and asylum seekers disembarked in Málaga, Motril, and Almería are detained in substandard, unsuitable facilities. Women and children traveling with family members are also detained at Motril and Almeria.

Málaga’s central police station has underground jail cells, which are in particularly poor condition, Human Rights Watch found. There is no natural light or ventilation, and during the visit the stench in the enclosed, dank space was overpowering. Even if, as police officials asserted, people who arrived by sea are never placed in cells with other detainees, these cells are wholly unsuitable for even short periods, Human Rights Watch said.

In Almería, where toilets are outside the locked cells, Human Rights Watch interviewed a woman who said that one of her three cellmates had felt ill all night and was unable to go to the bathroom. The other women detained at the time declined to be interviewed. An 18-year-old Ivorian man detained at the Almería port detention facility in March said that he and his cellmates resorted to urinating in a plastic bottle when the police were not available to let them go to the bathroom.

The Spanish human rights institute, the Defensor del Pueblo, has raised concerns about the Motril port facility since at least 2009, saying that cells should have proper beds, air conditioning, and better sanitary conditions. Several police unions have also complained about conditions, with the Sindicato Unificado de Policía (SUP) saying in early July that it should be temporarily closed. A police officer stationed in Motril asked Human Rights Watch to press for improvements to the facility, citing constant problems with the plumbing, freezing temperatures in the winter, mosquitos in the summer, and terrible smells due to poor ventilation when the cells are full.

Access to Asylum in Spain

There has been a notable increase in new asylum applications in Spain over the past several years. In 2015, the last year for which official government statistics are available, there were 14,887 new asylum applications – a 150 percent increase over the previous year. In 2016, Eurostat, the EU’s statistical service, reported 15,570 new applications. In the first quarter of 2017, Spain received 6,715 new applications.

These numbers remain low relative to other EU countries. The 2016 figures are just 1.3 percent of the total new applications filed in the 28 EU member states, and just 335 asylum seekers per million inhabitants. By comparison, Germany received 60 percent of all new applications in 2016, with 8,789 asylum seekers per one million inhabitants.

The largest national groups of applicants in Spain are Syrians, Ukrainians, and several Latin American nationalities, including Venezuelans. Sub-Saharan Africans constitute less than one-tenth, although they are the majority of those attempting to reach Spain by land and sea. According to the UN refugee agency (UNHCR), 51 percent of those entering Ceuta and Melilla and reaching the mainland by boat between January 2016 and May 2017 were from Guinea, Ivory Coast, or Gambia. The UNHCR representative in Spain, Francesca Friz-Prguda, has expressed concern about limitations on access to asylum in Spain, recalling that 25 percent of the world’s forcibly displaced people are sub-Saharan Africans.

While many migrants may not have protection needs, Spanish border policies may contribute to the low number of sub-Saharan Africans requesting asylum, Human Rights Watch said. In Ceuta and Melilla, denial of freedom of movement for asylum seekers to travel onward to the peninsula, and slow official transfers of asylum seekers from the enclaves to the mainland, appear to serve as a disincentive to applying for asylum. At Andalusian ports Human Rights Watch visited, limited information about their right to claim asylum and the lack of individual interviews with lawyers and judges may also deter people from applying.

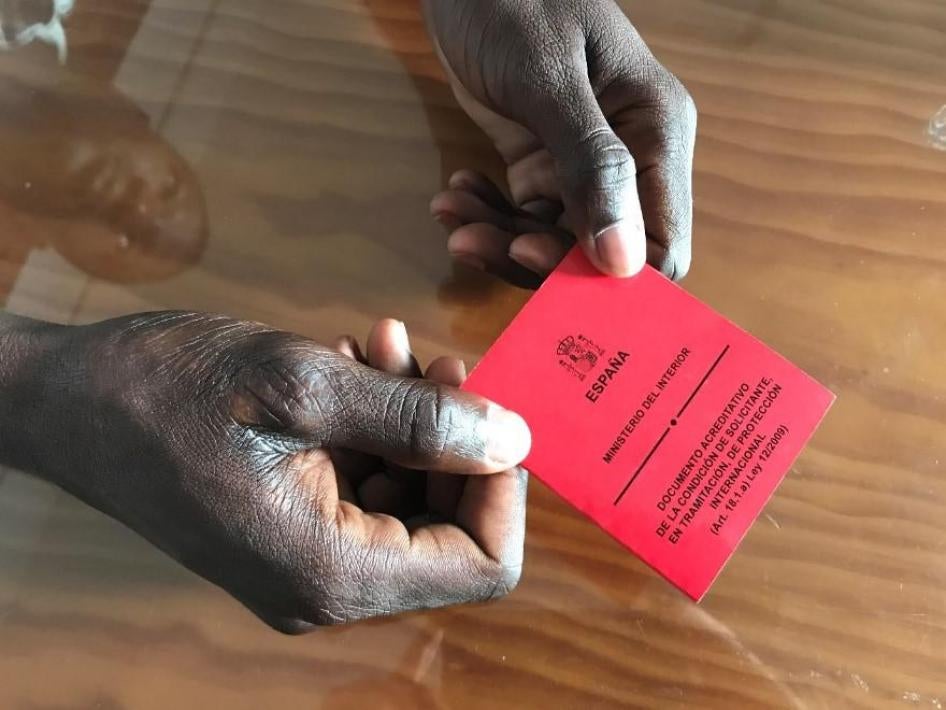

Various people interviewed said that the police actively discourage asylum applications in the Andalusian port facilities. Numerous migrants and asylum seekers said they had received basic information about the procedure and their rights from the Red Cross and UNHCR, which has two field officers in Andalusia who visit the ports, rather than from the police. Several said they first heard about the possibility of applying for asylum after they were remanded to an immigration detention center (Centro de Internamiento de Extranjeros, CIE) rather than during the initial 72-hour detention and registration period.

Oumar’s experience is typical. A 24-year-old from Mali, he was rescued by Salvamento Marítimo on March 22 and disembarked in Algeciras.

The lawyer came when we had to sign the paper [in police custody], he gave us a copy but didn’t explain what it was. The judge interviewed us as a group. She asked why we came, if we had any identity papers, if we had any family in Spain. I was scared. Everyone said they came for work, so I said that too. The lawyer didn’t say anything about asylum. It was the Red Cross at the Tarifa CIE that talked to me about asylum. I told them my story, and they said I could apply for asylum. So, I did.

Aristide, a 26-year-old from Ivory Coast, described the three days he spent in the Motril port police facility in early April:

They gave us food. we washed just once. I was always in the cell. They came to give us food and then would lock the door. The lawyer came, the judge came. They explained everything, but nobody mentioned asylum. They said they wanted to send us back, and that the lawyer could defend us.

By the end of May, when Human Rights Watch visited, only one person had applied for asylum in Almería out of roughly 1,200 people who had disembarked there since the beginning of the year. None of the roughly 800 people who had disembarked in Motril had applied for asylum. By contrast, in Málaga, 62 people out of roughly 450 had applied. The Málaga bar association trains lawyers who may be called to represent people arriving by boat, and members of the subcommittee on migration advise lawyers on duty via WhatsApp about their duties and obligations when a boat arrives.

Automatic Detention

Although Spain has invested more in its asylum system in recent years, the official reception system has capacity for only 5,125 asylum seekers, according to official statistics as of the end of May. Of these, 4,709 places are in shelters run by nongovernmental groups, while four government reception facilities can accommodate 416 asylum seekers. Andalusia has 1,126 reception places, by far the most of any region of Spain.

Under Spanish law, immigration detention is permissible when ordered by a judge and for the purposes of deportation, for a maximum of 60 days. Spain currently has seven immigration CIEs. In April, the interior minister announced an intention to open three more – Málaga, Madrid, and Algeciras. In July, the central government’s representative in Andalusia said the government was evaluating whether to open one in eastern Andalusia, where Almería and Motril are located, in response to the increase in boat migration.

The majority of adults arriving irregularly by sea appear to be sent to the detention centers virtually automatically, regardless of the effective possibility to enforce a return order. There are many reasons why a person cannot be deported, including lack of a bilateral agreement with the country of origin for such returns. According to Spanish data, the deportation centers with the lowest effective deportation rate are Algeciras, and Las Palmas and Tenerife, both in the Canary Islands – all subject to boat migration. The Algeciras detention center, which includes an annex in Tarifa, had the highest number of detainees in 2016 – 3,101 people – and the third-lowest effective return rate at 15 percent. People who cannot be deported are released but remain undocumented migrants with an obligation to leave the territory. They can be subject to renewed expulsion orders and detention.

Emmanuel, the 18-year-old from the Ivory Coast, said the Almería judge did a group videoconference hearing. The lawyer was at the police port facility with Emmanuel and the others: “The judge asked us how we got there and if we wanted to stay or go back to our countries. Everyone said they wanted to stay…They gave us a paper with our names, saying we would go to Valencia. I didn’t understand it was a prison.”

Patrick, a 27-year-old from Cameroon, like the other men interviewed in Motril, said he saw a lawyer only when it was time to sign the paper ordering his removal from Spain, and that the judge interviewed the migrants as a group. Before sending them to a detention center, the judge asked three questions, of which Patrick could remember only two: “Do you have family in Spain?” and, “Do you want to remain in Spain?”

The use of detention appears to be based on a flawed deterrence logic, Human Rights Watch said. The director of the Tarifa detention center said detention serves to “avoid a massive flow from Morocco to Europe. If they know that they’ll go straight to a shelter where people will help them get where they want to go, the flow would be much greater. We are the frontier of Europe.” An officer at the Algeciras CIE called the detention policy a “palliative measure, to avoid the pull factor.” But a body of research, including a UNHCR comparative study from 2011, has found no empirical evidence that the threat of detention deters migration or refugee flows.

Spain’s human rights institute, the Defensor del Pueblo, has repeatedly raised serious concerns about detention center conditions across the country, as have oversight judges. In May, Belén Barranco Arévalo, the oversight judge for the Algeciras center and its annex in Tarifa, issued a judicial order enumerating 31 urgent measures she considers “absolutely necessary” to comply with national and international law. The same judge had already strongly criticized conditions in both facilities in January, including overcrowding, the lack of recreational spaces and proper light, sufficient changes of clothing, including underwear, as well as the practice of locking people inside their rooms. The judge said the two facilities are “more typical of a prison regime,” and called them “deplorable.”

Under international and European law, detention pending deportation should be a last resort, implemented for the shortest time necessary, and is justifiable only insofar as authorities show due diligence in pursuing effective and safe deportation. The use of automatic detention as a deterrent measure is not permissible. Indeed, best practices point to the use of alternatives to detention, especially when deportation within a reasonable time is not foreseeable.

The detention of a child solely because of the child’s own migration status, or that of a parent, constitutes arbitrary detention and contravenes the principle of the best interest of the child. For these reasons, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child calls on states to “expeditiously and completely cease the detention of children on the basis of their immigration status.” These standards apply to family detention as well as to the detention of unaccompanied children.

Spain has alternatives to detention. People arriving by sea considered to belong to vulnerable groups, including families with children and pregnant women, are often taken directly to so-called humanitarian shelters. Many of those released from detention because they cannot be returned to their countries of origin are also placed in such shelters, where they may remain for up to three months. The directors of the Algeciras centers said the average length of stay was 15 to 20 days. National statistics show the average stay is around 24 days, including those who are deported as well as those who are released because they cannot be deported.