Summary

Since they destroyed [the Calais camp] last year, there is no place to sleep or eat. It’s like living in hell.

—Yeakob S., 29-year-old Ethiopian man, Calais, June 30, 2017

[T]he women and the men who first were coming from Syria, today are coming from Eritrea, or from many other countries, and who are fighting for freedom, must be welcomed in Europe, and especially in France.

—President Emmanuel Macron, Trieste, Italy, July 13, 2017

Nine months after French authorities closed the large migrant camp known as the “Jungle,” on the edge of Calais, between 400 and 500 asylum seekers and other migrants are living on the streets and in wooded areas in and around the northern French city.

Based on interviews with more than 60 asylum seekers and migrants in and around Calais and Dunkerque, and with two dozen aid workers working in the area, this report documents police abuse of asylum seekers and migrants, their disruption of humanitarian assistance, and their harassment of aid workers—behavior that appears to be at least partly driven by a desire to keep down migrant numbers.

Human Rights Watch finds that police in Calais, particularly the riot police (Compagnies républicaines de sécurité, CRS), routinely use pepper spray on child and adult migrants while they are sleeping or in other circumstances in which they pose no threat; regularly spray or confiscate sleeping bags, blankets, and clothing; and sometimes use pepper spray on migrants’ food and water. Police also disrupt the delivery of humanitarian assistance. Police abuses have a negative impact on access to child services and migrants’ desire and ability to apply for asylum.

Such police conduct in and around Calais is an abuse of power, violating the prohibition on inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment as well as an unjustifiable interference with the migrants’ rights to food and water. International standards provide that police should only use force when it is unavoidable, and then only with restraint, in proportion to the circumstances, and for a legitimate law enforcement purpose.

Authorities have turned a blind eye to widespread reports of police abuse against asylum seekers and other migrants. Vincent Berton, the deputy prefect for Calais, strongly rejected reports that police used pepper spray and other force indiscriminately and disproportionately. “These are allegations, individuals’ declarations, that are not based on fact,” he told Human Rights Watch.

In March 2017, local authorities barred humanitarian groups from distributing food, water, blankets, and clothing to asylum seekers and migrants. A court suspended those orders on March 22, finding that they amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment. The French ombudsman (Défenseur des droits) has also criticized these and other measures taken by local authorities, concluding that they contribute to “inhuman living conditions” for asylum seekers and migrants in Calais.

As of the end of June, authorities were allowing a single two-hour humanitarian distribution each day, in an industrial area near the former migrant camp. In addition, a local priest permitted a lunchtime distribution to take place on church grounds. Police regularly disrupted other distributions of humanitarian assistance. Aid workers described one occasion when gendarmes bearing rifles surrounded them, and multiple occasions where riot police otherwise forcibly blocked migrants’ access to aid workers and knocked food out of the workers’ hands when they attempted to give food to migrants.

Aid workers have begun to photograph or film these acts by police, as they are allowed to do under French law. In response, they say police have at times seized their phones for short periods, deleting or examining the contents without permission.

Aid workers also say that police regularly subject them to document checks—sometimes two or more in the space of several hours. Identity checks are lawful in France but are open to abuse by police. In Calais, identity checks of aid workers have delayed humanitarian distributions. They also prevent aid workers from observing how police treat migrants when they disperse people after distributions.

President Emmanuel Macron has committed to take a humane approach to refugees and asylum seekers. On July 12, his government announced initiatives that would improve access to asylum procedures and provide additional housing and other support for asylum seekers and for unaccompanied children. These welcome steps stand in sharp contrast to the treatment asylum seekers and other migrants are currently experiencing in Calais.

To live up to these commitments and France’s international obligations, local and national authorities should immediately and unequivocally direct police to adhere to international standards on the use of force and to refrain from conduct that interferes with the delivery of humanitarian assistance, subject to appropriate disciplinary action for abuse of authority or other misconduct.

The Ministry of the Interior should remove obstacles that impede access to refugee protection, including by either establishing an asylum office in Calais or by facilitating applications in existing offices by those who wish to make them. It should also work with appropriate agencies and humanitarian groups to provide access to accommodation for all asylum applicants, including emergency accommodation for any undocumented migrant without shelter in Calais.

Finally, local and national authorities should ensure that unaccompanied migrant children have access to child protection services, including shelters with sufficient capacity and adequate staffing.

Recommendations

To the French Government

- Municipal and departmental authorities and the Ministry of the Interior should immediately and unequivocally direct riot police and other police forces not to use pepper spray or other force on migrants who are asleep, or in other circumstances where use of force is disproportionate to a legitimate objective.

- Calais municipal authorities should immediately comply with the June court order directing the municipality to establish water distribution points, and toilets and showers, and to take other steps to protect the rights of asylum seekers and migrants.

- The Ministry of the Interior should establish an office (guichet unique) in Calais to allow those who wish to seek asylum to do so, or should facilitate their transport elsewhere in France to enable them to submit applications at an existing asylum office.

- The French government should comply with its obligations under the European Union (EU) reception directive and as soon as possible provide accommodation to all asylum applicants who lack sufficient means to provide for themselves while their claims are processed, from the moment a person indicates an intention to seek asylum. The government should also work with humanitarian and nongovernmental groups to help arrange emergency accommodation for any undocumented migrant without shelter in Calais. Such accommodation need not be in northern France.

- Local and national authorities should ensure that unaccompanied migrant children are promptly identified, informed of their right to seek asylum in France and receive the necessary legal support to do so, and have access to child protection shelters with sufficient capacity and adequate staffing.

- As the European Union’s Fundamental Rights Agency recommends, police should provide a written record, or stop form, for every document check to encourage well-grounded stops and greater accountability. Stop forms should at a minimum include the name and age of the person being stopped, the legal grounds for the stop, the outcome, and the name and unit of the police officer(s) who conducted the stop.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch interviewed 61 asylum seekers and migrants, including three women and one girl, in and around Calais and Dunkerque at the end of June and beginning of July 2017. Thirty-one identified themselves as children under the age of 18.

The total comprised eighteen from Eritrea, sixteen from Afghanistan, eleven who described themselves as Ethiopian and a further nine who specified that they were Oromo (Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group), five Iraqi Kurds, and two from Pakistan.

In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed two dozen aid workers who distribute food, provide medical or legal services, or offer information and other support to asylum seekers and migrants in the departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais, and we met with the deputy prefect for Calais and with other local authorities, as well as with the directorate of asylum of the Ministry of the Interior in Paris.

Human Rights Watch researchers conducted most interviews in English or French, and in some cases in German or Italian. We explained to all interviewees the nature and purpose of our research, that the interviews were voluntary and confidential, and that they would receive no personal service or benefit for speaking to us, and we obtained verbal consent from each interviewee.

All names of migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees used in this report are pseudonyms. We have also withheld the names and other identifying information of aid workers who requested that we not publish this information.

In line with international standards, the term “child” refers to a person under the age of 18.[1] As the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child and other international authorities do, we use the term “unaccompanied children” in this report to refer to children “who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so.”[2] “Separated children” are those who are “separated from both parents, or from their previous legal or customary primary care-giver, but not necessarily from other relatives,”[3] meaning that they may be accompanied by other adult family members.

I. Asylum Seekers and Migrants in Calais

Until the end of October 2016, a sprawling, squalid shantytown on the edge of Calais, known colloquially as “the Jungle,” held between 6,000 and 10,000 refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants, including many unaccompanied children. Many had fled persecution or violence in their home countries. All had endured significant hardship on their journeys to Europe and on to northern France. The location of the camp near Calais reflected a desire by many of those living there to continue their journey on to the United Kingdom.

City authorities considered the camp an eyesore and regarded the men, women, and children staying there as nuisances. Aid workers, United Nations officials, and casual visitors were shocked by the deprivation they saw there. In a larger sense, the camp was a symbol of Europe’s shame, a visible reminder of the European Union’s failure to find a humane, fair, and coordinated approach to migration and to refugee flows.

In October 2016, the camp was demolished and its residents relocated to emergency shelters across France. National and local authorities hoped that its closure would mark a new chapter for the city and the region, and possibly for France’s treatment of refugees.[4]

Many of the asylum seekers and migrants who left the camp shared those hopes. As relocations began, groups of camp residents packed their bags and assembled with varying degrees of resignation, trepidation, optimism, and ebullience. Some waved French flags. By the end of the week, over 5,000 children and adults had been relocated, a significant achievement. The prefect of Pas-de-Calais, Fabienne Buccio, declared, “Our mission is accomplished.”[5]

Nevertheless, it was obvious even then that her statement was premature. Aid groups had warned that authorities were systematically undercounting unaccompanied children in the weeks leading up to the camp’s closure, raising the risk that they would be unprepared for the numbers that would need alternative accommodation.[6] At least 100 unaccompanied children and hundreds of adults were still waiting in line to be relocated when authorities announced that registration had ended, meaning that they spent another night in the camp.[7]

The new centers French authorities set up for unaccompanied children were not part of the regular child protection service, where unaccompanied migrant children are usually placed. These facilities, known as Reception and Orientation Centers for Unaccompanied Minors (Centres d’accueil et d’orientation pour mineurs isolés, CAOMI), were set up at short notice, with staff hired rapidly.

When Human Rights Watch interviewed unaccompanied children and staff at reception centers in France’s Nouvelle-Aquitaine, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, and Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur regions, we found that while some centers were run by professional staff with experience in refugee support, others were managed by organizations and individuals without such experience. Many centers also lacked regular access to translators, making it impossible for some children to communicate with staff.[8]

The centers were temporary, intended to be in operation for only a few months, since

French authorities assumed the United Kingdom would accept a significant number of unaccompanied children from Calais. As a result, these “provisional” centers did not immediately give unaccompanied children information about the possibility of claiming asylum in France and did not give them access to French asylum procedures for several months.[9]

As well as the expectation that unaccompanied children with family ties to the UK would be accepted for transfer, French authorities hoped that their British counterparts would make broad use of a UK humanitarian provision enacted in 2016 which covered unaccompanied children with no such ties. When UK lawmakers passed the measure, known as the “Dubs amendment,” they spoke of accepting thousands of children from across Europe. In February, however, the Home Office said that it would admit no more than 350 children under the provision.[10] In April, British authorities said the UK would accept an additional 130 children under the Dubs amendment.[11]

The Home Office confirmed in written answers to the House of Commons that the UK had taken 200 children from Calais in 2016 under the Dubs amendment and, as of mid-July, had not accepted a single child for transfer under the provision in 2017.[12]

Although the UK accepted some 300 children with family members in Britain, under an EU regulation known as the “Dublin III” framework, Human Rights Watch and other groups found that some children with aunts, uncles, or grandparents in the UK were not approved for transfer even though they appeared to meet the regulation’s requirements. The Home Office did not explain the basis for these decisions, and it was not clear under what process, if any, children could seek review.[13]

Unaccompanied children had already begun to leave the temporary reception centers on their own in December, when Human Rights Watch visited them. By March, when the last of the centers closed, over 700 unaccompanied children had abandoned them, according to official records viewed by Human Rights Watch.

Many of these unaccompanied children initially made their way to Paris, where they and other children and adults slept on the roadside, under bridges, and along the riverbank of the Porte de La Chapelle area of the city, in the vicinity of a new aid center for migrants that had reached capacity shortly after it opened.[14]

Nine months after the Calais camp’s closure, between 400 and 500 asylum seekers and other migrants are staying on the streets and in wooded areas in and around Calais, according to humanitarian workers. It is not clear how many are unaccompanied children, but aid workers estimated that the number was at least 50 and as high as 200 or more, based on their observations during food distributions.[15] Vincent Berton, the deputy prefect for Calais, told Human Rights Watch, “There are many young children, 14 or 15 years old, especially Eritreans.”[16]

An additional 300 to 400 asylum seekers and migrants stay in informal camps near Dunkerque, aid workers told Human Rights Watch. That number includes about a dozen children who are with their families, who tend to stay in these and in smaller camps scattered elsewhere in the departments of Nord and Pas-de-Calais instead of in Calais itself.[17]

These asylum seekers and migrants told Human Rights Watch they live in very difficult circumstances, in some cases for several months or more. “People here in Calais are in very, very bad conditions,” said Yeakob S., a 29-year-old Ethiopian man.

He added, “Since they destroyed [the Calais camp] last year, there is no place to sleep or eat. It’s like living in hell.”[18] Kuma N., a 16-year-old boy who, like others from his ethnic group, referred to himself as Oromo instead of Ethiopian, told us, “I’ve been here for 14 months. I sleep outside. I’m very sick.”[19] Biniam T., a 17-year-old from Ethiopia, said, “I risked my life for freedom. I didn’t expect such treatment in Europe.”[20]

The French ombudsman observed on June 14, after visiting Calais, that the children and adults in and around the city were “in a state of physical and mental exhaustion.”[21] Aster N., a 17-year-old girl from Ethiopia, said:

If our country were at peace, no one would select this life. Who would want to live like this? Who would choose this situation? If we and our families were safe in our countries, why would we come here?[22]

Aid workers, including staff and volunteers with the nongovernmental organizations L’Auberge des Migrants, Help Refugees, and Utopia 56, have regularly distributed food, water, sleeping bags and clothing, medication, and other essentials to asylum seekers and migrants in these areas. In Dunkerque and other areas of the department of Nord, aid groups have been able to carry out such distributions unhindered.

In and around Calais, however, riot police and the gendarmerie frequently halted most distributions until 12 humanitarian groups brought a successful legal challenge to these practices in early 2017.[23]

The Lille administrative tribunal issued a ruling on March 22 finding that authorities had subjected migrants to inhuman and degrading treatment by preventing food distributions.[24] In response to the rulings, the prefecture allowed a single distribution per day, initially for one hour, and sometimes for up to 90 minutes.[25] On June 17, the day after aid groups filed a second court challenge, the prefecture extended food distributions to two hours each day.[26]

The administrative tribunal’s ruling in the second case, issued on June 26, also directed authorities to provide migrants with access to drinking water, toilets, and facilities for showering and washing clothes, giving authorities 10 days to implement the ruling.[27] On July 6, at the end of the 10-day period, the prefect of Pas-de-Calais announced that the state had appealed the tribunal’s ruling.[28]

The decision to appeal the ruling is consistent with local authorities’ frequently expressed desire to avoid re-establishing a migrant camp on the city’s fringes. In court proceedings and in media statements, municipal authorities have regularly stated that humanitarian services for migrants create an implication of permanence (un point de fixation) and attract more migrants to the region.[29] During a June 23 visit to Calais, the French minister of the interior, Gérard Collomb, echoed these sentiments.[30]

At the same time, President Emmanuel Macron has committed to take a humane approach to refugees, promising to reform an asylum system that he has described as “completely swamped” and that “does not permit humane and just consideration of requests for protection.”[31] Similarly, ahead of his election in May 2017, his campaign platform spoke of the need for France to take “its fair share in the reception of refugees.”[32]

On July 12, Macron’s government announced initiatives that would reduce delays in access to asylum procedures, increase accommodation for asylum seekers, augment reception facilities and services for unaccompanied children, and speed up refugee resettlement from countries near conflict zones.[33] Referring to these initiatives, Macron stated:

I want to do this in a combined spirit of humanity, intellectual rigor, and effectiveness in practice. In the spirit of humanity because the women and the men who first were coming from Syria, today are coming from Eritrea, or from many other countries, and who are fighting for freedom, must be welcomed in Europe, and especially in France. Therefore we will obviously do our part in this fight.[34]

These undertakings are largely welcome, but they sit uneasily with the statements of the minister of the interior. In particular, it is difficult to reconcile Macron’s stated commitment to humane treatment of refugees and asylum seekers with authorities’ opposition to the provision of drinking water and other basic needs to asylum seekers and migrants in Calais.

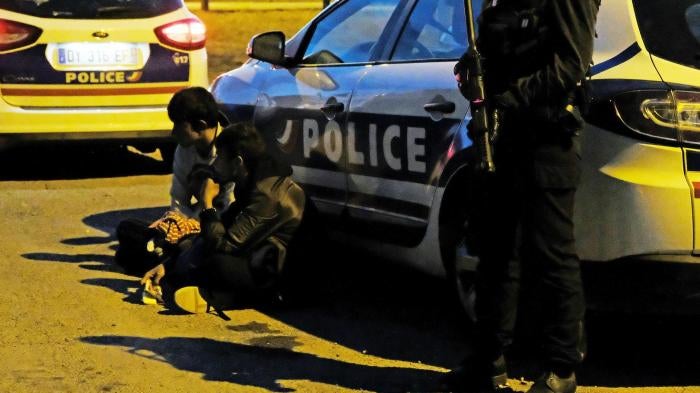

II. Police Abuse of Asylum Seekers and Migrants

Nearly every asylum seeker and migrant whom Human Rights Watch interviewed reported frequent use of pepper spray by police—usually members of the riot police—in circumstances that indicate the use of force was excessive and disproportionate, in violation of international standards.

The frequent and abusive use of pepper spray appears, in the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, to serve no purpose other than to harass migrants, presumably to encourage them to leave Calais. Such police behavior is a violation of the prohibition on inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment under human rights law.

The accounts suggest that police use pepper spray most frequently at night, on asylum seekers and migrants who are asleep or whom they have just woken up. Pepper spray, a chemical agent designed to subdue people who are behaving violently, causes temporary blindness, severe eye pain, and respiratory difficulties—generally for between 30 and 40 minutes. Food and water that have been sprayed cannot be consumed, and sleeping bags and clothing must be washed before they can be reused.

In a typical account, Nebay T., a 17-year-old boy from Eritrea, told Human Rights Watch:

The spraying happens nearly every night. The police come up to us while we are sleeping and spray us. They spray all over our face, our eyes.[35]

Moti W., a 17-year-old Oromo boy, said:

This morning, I was sleeping under the bridge. The police came. They sprayed all over our face, hair, eyes, clothes, sleeping bag, food. Many people were sleeping then. The police sprayed everything.[36]

Abel G., a 16-year-old Eritrean boy, stated, “If you are sleeping, they just point it down

at you.”[37]

In most cases, according to asylum seekers and refugees, police employ pepper spray without any warning. “They didn’t say anything, only sprayed,” an Afghan man, Mirwas A., said.[38] “I was sprayed in the face,” another Afghan man, Yahya R., told us.[39]

In some instances, police appear to issue perfunctory warnings before spraying asylum seekers and migrants. Asked if police say anything before they spray, Abel G., the 16-year-old Eritrean boy, told us, “Sometimes. They say, ‘Allez, allez.’ They speak French. We don’t know what else they are saying.”[40] In another case, Wahid N. told us that several days before we spoke, an officer had jostled him with a boot to wake him up before spraying him in the face early in the morning.[41] In a third account, Eba J., a 15-year-old Oromo boy, said, “They wake us up. ‘Allez, allez,’ they say. But where can I go? After that, they come with spray.”[42]

In addition, we heard reports of police spraying asylum seekers and migrants who are walking along the road in isolated areas. For example, Layla A., an 18-year-old woman interviewed at the beginning of July, told Human Rights Watch:

I was walking on the road two days ago. The police came by and used spray. This was at night, a little after 8:00 p.m., when they passed by the distribution point in their cars. They opened the window and sprayed.[43]

In another such account, 16-year-old Abel G. reported, “If they get you on the street somewhere, they spray you from the vehicle as they drive by.” He told Human Rights Watch police had sprayed him with pepper spray in this way the day before we spoke to him at the end of June. He identified them as riot police by the patches on their uniforms and the emblem on the vehicle.[44] In a third account, Biniam T., a 17-year-old boy from Ethiopia, described being sprayed with pepper spray by riot police one week earlier:

It was the daytime, and they came in a van. They sprayed us from the van. They didn’t say anything; they just sprayed.[45]

In some instances, asylum seekers and migrants, as well as aid workers, also reported that police used pepper spray when they broke up food distributions, particularly those that occur late at night. Saare Y., a 16-year-old Eritrean boy, said:

Last night after dinner, the police came. ‘Go, go, go,’ they said. One of them caught me. He held onto my left arm, and another police officer came up to me and sprayed me in the eyes. The spray also went into my nose.[46]

We heard similar accounts from other boys who said that police had sprayed them in the eyes during or immediately after food distributions.[47] A humanitarian worker described one such instance that he and a second worker witnessed at a late-night food distribution at the end of June. “I saw two policemen spray [a boy] in the eyes. He took a few steps and then dropped to the ground, on his knees.” The two aid workers retrieved eyedrops from the distribution van, and police allowed them to treat the boy. “Then the police made him move on when he could walk,” the humanitarian worker told Human Rights Watch.[48]

Another boy from Eritrea, Birhan G., age 16, described his treatment by police at a late-night food distribution two days earlier:

It was about midnight. I came to get food. The police were there. They told the group, ‘You don’t give out food.’ We are hungry. We are thirsty. Then the police sprayed us, and we ran. We fell down as we ran into the woods, and the police laughed at us.[49]

Aid workers told us they regularly hear similar accounts. “Yesterday I saw a child who told me police sprayed him in the face. He was having problems with his eyes. Another child who also said he was sprayed in the face had an allergic reaction to the spray,” said Arthur Thomas, a youth protection coordinator with Refugee Youth Service and L’Auberge des Migrants.[50] A health worker told Human Rights Watch that the group she works with regularly sees injuries linked to the use of pepper spray.[51] In our visits to food distribution sites at the end of June, we saw children with bandages under their eyes; when we asked why, they told us police had sprayed them in the face the previous night.

Describing the feeling of being exposed to pepper spray, 16-year-old Abel G. said, “You cry. You feel very hot in your face. It closes up your throat. You can’t breathe.”[52]

Others who had been sprayed gave similar descriptions. “My face is burning. It feels like I’m on fire,” Meiga T., a 16-year-old Oromo boy, told us.[53] Another Oromo boy, Demiksa N., age 15, said:

After the spray, you’re confused. It’s like you don’t know anything; you can’t think. You don’t see anything, you don’t remember anything. You feel like it might be better to kill yourself.[54]

A 1999 North Carolina Medical Journal study that continues to be a reference point for research on the effects of pepper spray, or oleoresin capsicum, found that it can cause eye burns and abrasions, asthma attacks, acute high blood pressure, chest pains, and loss of consciousness, adverse effects severe enough to warrant hospitalization.[55] The use of pepper spray in detention settings is known to result in increased injuries if those who are sprayed cannot remove it thoroughly within an appropriate period of time.[56]

When British lawmakers requested expert evidence on the short- and long-term effects of pepper spray on children’s health and well-being, they heard that “research on the exposure to children is uncommon, possibly because no expert believes these agents would ever be used on children.”[57] A 2007 review of research on the health effects of pepper spray noted that “[n]ot one single study examined recommended pepper spray as safe for use on children.”[58]

Police use of pepper spray in Calais is so common that many asylum seekers and migrants had difficulty recalling precisely how many times they had been sprayed. “This happens almost every day,” 16-year-old Meiga T. reported.[59] “I have been sprayed so many times,” Hakim T., an 18-year-old Ethiopian man, told us, adding that police had used pepper spray on him the night before we spoke. “Whenever the police find us on the road or in any open area, they spray us,” he said.[60] “This is normal for us. It’s part of our life,” Biniam T., a 17-year-old Ethiopian boy, said matter-of-factly.[61]

Arthur Thomas, the youth protection coordinator with Refugee Youth Service and L’Auberge des Migrants, told us that he tried to convince a child who had been sprayed in the face to make a report:

He’s not interested. He doesn’t perceive what happened as something that authorities will change. For him it’s just normal—this is something that happens every day.[62]

Police also frequently spray sleeping bags, blankets, and extra clothing, asylum seekers and migrants reported. Describing his experience the previous week when he awoke to find police using pepper spray on him, Jalil M., an Afghan man, said, “The police sprayed all over everything, over all of our blankets and clothing.”[63]

In addition, police regularly confiscate sleeping bags and other items after asylum seekers and migrants have fled the immediate area to avoid being sprayed. Hassan E., a 17-year-old Ethiopian boy who had received blankets from an aid group earlier in the week, told us:

Two nights ago, I was sleeping. The police came. They took everything—all our blankets and sleeping bags.[64]

Wako L., a 15-year-old Oromo boy, said, “This morning the police came, so I have no sleeping bag. The police took it. They sprayed it.”[65]

The accounts we heard suggest that the use of pepper spray on people, bedding, and clothing is routine. Seventeen-year-old Biniam T. said:

If they catch us when we are sleeping, they will spray us and take all

of our stuff. Every two or three days they do this. They’ll come and

take our blankets.[66]

Saare L., a 16-year-old Ethiopian boy who described being sprayed in the eyes, said, “This was not the first time this happened. It happens all the time.”[67] Hiwa S., a 21-year-old Kurdish man, said, “Every day, they take our sleeping bags, blankets, water.”[68] In a similar account, Negasu M., a 14-year-old Oromo boy, told Human Rights Watch, “When the police find me, they spray me. They take my blanket. Sometimes they take my shoes. Sometimes they take my clothes…I try to change the place where I sleep.”[69]

Aid workers also told us they regularly hear such reports from migrants. “I’ve had guys tell me many times that they were sprayed by police. One still had red in his eyes when I saw him. This is a regular thing,” a law student volunteering with L’Auberge des Migrants said, adding: “One guy came to the distribution without shoes or a jacket. A colleague asked him what happened. He told her, ‘The police took my shoes, took my jacket.’”[70]

Asylum seekers and migrants frequently told Human Rights Watch that police were careful to avoid the use of pepper spray in the presence of aid workers. “I wish you could be here in the night, when we are sleeping,” Gebre M., 16, said.[71] When we spoke to another boy at a midnight distribution, 17-year-old Kojo D., he told us, “As soon as you leave, the police will come and spray.”[72]

In mid-July, however, we heard from some aid workers that they had also been sprayed by police. One humanitarian worker told Human Rights Watch:

We’re now getting situations of volunteers being pepper-sprayed. I got pepper-sprayed two days ago…. I was only distributing water.

He explained that he and a colleague were at the Rue des Verrotières distribution site at about 1:00 a.m. on July 16. “We stopped because of a guy with a broken leg, on crutches. He just wanted some water,” the humanitarian worker said.[73] His colleague confirmed this account, adding that a member of the riot police sprayed the two of them along with the group of migrants to whom they were distributing water. The officer sprayed them “from eye level downward,” she said, from a distance of about one meter.[74]

We also heard numerous reports that police on occasion intentionally pepper spray food and water. Nasim Z., an Afghan man, told Human Rights Watch that police had intentionally sprayed his food, so that he went hungry that night.[75] Describing a similar instance, a humanitarian worker with Utopia 56 said she had given two water tanks to a group of men and boys, who told her the next day that police had sprayed the water in the containers.[76] Sarah Arrom, also with the humanitarian organization Utopia 56, reported that she has heard numerous such accounts.[77]

Such practices are profoundly demeaning and make life extremely uncomfortable for migrants and asylum seekers. “The whole night I didn’t sleep. It was very cold. We didn’t have any blankets. They took everything,” 17-year-old Biniam T. said.[78] “Yesterday, we had no dinner. There was food coming at midnight,” Hassan E., also 17, said, referring to a late-night distribution by an aid group. “The police said, ‘No dinner.’”[79]

Most asylum seekers and migrants, as well as the aid workers we spoke to, believed that the sole purpose of these policing practices is to drive migrants and asylum seekers away. “The police take all our blankets so we can’t stay in the forest,” Hakim T., 18, said.[80]

In addition to using pepper spray, police, according to some asylum seekers and migrants, have on occasion struck them with batons or kicked them when ordering them to leave food distribution sites or other locations. For example, Abel G., a 16-year-old boy from Eritrea, told us:

A few days ago, we came to this place [where aid workers were distributing food to migrants]. The police said, “No more food.” One police came up to me and hit me with his baton. He didn’t swing it; it was like he didn’t want to be seen, so he hit me like he was punching. It hit me here, in the ribs. It hurt so much.[81]

Aid workers said that asylum seekers and migrants had told them similar accounts. In one incident at the beginning of June, Sarah Arrom, of Utopia 56, said:

We were standing at the food distribution on Rue des Verrotières, and we saw an Eritrean boy, 16, riding his bike. His face was cut, and we asked him what happened. He explained that a police car had stopped and asked him for his papers. Then they pushed him, and he fell on the ground. He was bleeding a lot when we saw him.[82]

In addition, humanitarian workers reported that they occasionally witnessed police threaten asylum seekers and migrants. For example, a law student volunteering with L’Auberge des Migrants told us that on May 28, when she was in the large field observing the evening food distribution:

I saw a police officer look around and heard him say, “What are all these sons of a bitch…” I wrote that down, and when I looked up and saw him with his baton raised at a refugee. He told the refugee, “Go on, go into the woods or I’ll smash your mouth.”[83]

Children and adults told us that the treatment they received from police was taking an emotional toll. “Now my head is confused,” said Waysira L, a 16-year-old Oromo boy. “I’ve only been here two months. Every day, the police chase us. They use spray. They kick us. This is our life every day.”[84] Another Oromo boy, Gudina W., also 16, said:

When I sleep tonight, I will see the police. I’ll wake up and realize I have

been dreaming that the police are coming to hit me. This is what I see in

my dreams.[85]

“This is harassment, and at some point it can break your mind. It makes you feel like an animal,” said Sarah Arrom of Utopia 56.[86]

Humanitarian groups in Calais have raised concerns about excessive use of force by French police, particularly the riot police, for several years. In May 2015, for instance, members of the local group Calais Migrant Solidarity posted a video filmed that month that appeared to show riot police pushing, kicking, and beating migrants who tried to hide in trucks while they seemed to pose no threat, and spraying pepper spray in their direction even as the migrants were leaving the road.[87]

Similarly, in late 2014, Human Rights Watch interviewed dozens of migrants who described routine abuses by police when they tried to hide in trucks or as they walked in town. Twenty-one migrants, including two children, said police had used pepper spray on them; nineteen described other acts of police violence, including beatings. Authorities denied these accounts.[88]

International standards call for police to use non-violent means “as far as possible” before resorting to the use of force. If the use of force is unavoidable, its use should be restrained and in proportion to the seriousness of the offense and the legitimate objective law enforcement officials seek to achieve.[89] Similarly, France’s Code of Ethics of the Police and Gendarmerie provides, “Police and gendarmerie personnel use force within the framework established by the law, only when it is necessary, and in a manner proportionate to the purpose to be reached, or to the gravity of the threat, depending on the situation.”[90]

The numerous, consistent accounts Human Rights Watch received, together with reports from the French ombudsman and other groups,[91] strongly suggest that the riot police and other police forces are not complying with international and national standards. The use of pepper spray is a form of force, and its use on children and adults who are asleep is disproportionate and violates the international prohibition on ill-treatment. The same is true of the use of pepper spray on children and adults who are walking along roads or who otherwise do not pose a threat to law enforcement officials or to others.

The reported destruction or confiscation of blankets, sleeping bags, and other personal property of migrants appears to lack any legal basis. The consistent, detailed accounts of such acts suggest that riot police and members of other police forces have engaged in arbitrary conduct that may well constitute crimes.

Vincent Berton, the deputy prefect for Calais, vehemently rejected reports that police used pepper spray and other force indiscriminately and disproportionately. He told Human Rights Watch:

These are allegations, individuals’ declarations, that are not based on fact. They are slanderous…. The police are the administrative body that is the most controlled, and must comply with very strict codes and rules of ethics.

Asked specifically whether police in Calais had used pepper spray on sleeping migrants, he replied, “I have never seen or heard that. I did not give such orders. For me, this doesn’t exist.” However, he added, “If tear gas or spray was used gratuitously, it would be completely reprehensible and would violate the rules governing the use of force.”[92]

III. Police Disruption of Humanitarian Assistance

In addition to confiscating or destroying food, water, and blankets, migrants and aid workers said that police have regularly prevented the distribution of humanitarian assistance, without apparent legal basis. Such actions have left asylum seekers and migrants without basic necessities.

As of the end of June, authorities were generally allowing a single two-hour evening distribution per day but often arbitrarily halted other distributions. Earlier in 2017, local authorities had attempted to end food distributions altogether, issuing orders in February and March barring humanitarian groups from conducting such activities. The Lille administrative tribunal suspended these orders on March 22, finding that:

[T]he Mayor of Calais infringed in a grave and manifestly illegal manner on freedom of movement, on freedom of association and, by obstructing the fulfilment of migrants’ basic and vital needs, on their right not to be subjected to inhuman and degrading treatment.[93]

In response to this court decision, local authorities began to allow food distributions but limited them to one hour, after which, aid workers said, police on occasion moved aggressively to halt the distributions. The basis for limiting distributions to one hour was unclear: La Voix du Nord, a local newspaper, quoted some police as saying the order came from the minister of the interior; others said that the question was a “delicate” one.[94]

An aid worker described the police response to a distribution she took part in with two other aid workers outside the Calais train station in May. “The gendarmerie surrounded us, seven of them. They surrounded the car with rifles and didn’t allow us to leave,” she told Human Rights Watch. The gendarmes told the three aid workers that they were not allowed to distribute food. “We were stopped for about an hour,” she said, and then told to leave.[95]

In early June, police appeared to be following new orders. “Police told us that under new instructions from the subprefecture, beginning on June 1, all food distributions in Calais would be forbidden, except between 6:00 and 7:00 p.m. at the Rue des Verrotières,” Loan Torondel, of L’Auberge des Migrants, told us, referring to a large field in an industrial area of Calais not far from the site of the large migrant camp demolished in October 2016. “We can’t contest this decision because there’s no document. The police say it’s the deputy prefect’s decision, but it’s difficult to prove that without anything in writing.”[96] When Human Rights Watch asked the deputy prefect about these reports, he replied:

We have never banned distributions of water or food. The State is

accused by associations, so it is defending itself. These allegations

seem inaccurate.[97]

Nevertheless, a third humanitarian worker told Human Rights that police prevented a food distribution in early June:

They [the police] got physical with us. They pushed me around at one point…. A CRS agent told me I was on private land. They said I wasn’t allowed to be there. We were parked on the road at that point, and we were standing in the road, so that was not true. I stayed where I was, and the officer tried to rip the food out of my hand. Then more CRS agents came over and dragged me to the other side of a line they’d made. A lot of food was lost in the process. They didn’t let us leave the area. They…surrounded us and physically prevented us from leaving the space. This lasted for a few hours.

The humanitarian worker said that even though it was a very hot day, they were not allowed to give out water. “The CRS agents we spoke to weren’t sure. They went to go speak to their supervisor. That supervisor spoke to his supervisor. Finally they told us the order came down from the police chief—no, no water.”[98]

This was not an isolated incident. The same humanitarian worker described similar police responses to other food distributions in which he participated in early June:

Sometimes I would be handing out boxes, and CRS would come up and say it wasn’t allowed. Sometimes we would walk around them and keep handing out the food. We had food knocked out of our hands. Sometimes CRS would take the food off the table we had set up to distribute it.[99]

Riot police sometimes also closed the doors of the vans used for delivery of food and other assistance, shutting aid workers inside, other humanitarian workers told us.[100]

The humanitarian worker who reported that riot police had dragged him said:

One of my team that day had a printout of the French law against assisting migrants and refugees. The law provides for exceptions if the assistance is necessary for migrants’ physical well-being. We’re not asking for anything for the food we give. We’re not providing them with transportation anywhere. We’re not calling for them to have the legal right to stay in the country. We explained the law. The police didn’t respond.[101]

A humanitarian worker with Utopia 56 told Human Rights Watch, “They [the police] are always telling migrants to leave. Always. They don’t know the law. They always say that what we do is illegal.” She described an example on June 17 in which authorities again halted a late-night food distribution that was taking place in a large field off the Rue des Verrotières, situated in an industrial area of Calais not far from the site of the large migrant camp demolished in October 2016. “There’s a big new fence. They put [all the migrants] on the other side of the fence. One migrant asked me to give him food.” Riot police had ordered the group to close the van used for food distributions. “The food was out, on a rock; it wasn’t in the van. I took it and started to walk toward the migrants. CRS came in front of me and stopped me. He said, ‘No, no, no. I told you to stop.’ But there is nothing in the law that stops distribution of food.”[102]

On June 26, another order by the Lille administrative tribunal directed authorities in Calais to take steps within 10 days to improve conditions for migrants, including by establishing distribution points for water, toilet and washing facilities.[103] Municipal authorities immediately announced that they would appeal the decision and stated that they would not comply with it in the meantime—even though the appeal would not automatically stay the court’s order, meaning that they are legally obligated to follow it until the appeal is decided. Municipal authorities and the Ministry of the Interior filed the appeal on July 6, the day the order took effect.

The June order did not address food distribution, but a municipal official came to the Rue des Verrotières evening distribution the same day and announced that, going forward, the time period would be extended to two hours.[104] Thereafter, aid workers told us that Rue des Verrotières evening distributions were usually permitted between 6:00 and 8:00 p.m.

Human Rights Watch researchers observed that police allowed the evening distributions on June 28, 29, and 30 to go forward during these hours. Police ended distributions on June 28 and 29 shortly after 8:00 p.m. (Aid workers ended the June 30 distribution just before 8:00 p.m., after a fight broke out between two migrants.)

At the same time, police continued to halt distributions taking place later in the evening. Describing a June 27 night-time distribution, a humanitarian worker reported that shortly after he and his colleagues began to distribute food, “the CRS came in eight or nine vans. They told us to stop. The CRS officers walked in a big line, holding their batons in their hands. Some had riot shields. They checked all the volunteers’ IDs, twice.” As the police line advanced, migrants retreated across the field and into nearby woods.[105] Human Rights Watch researchers observed two night-time distributions that police interrupted in the same way on June 29.

Other aid workers, asylum seekers, and migrants said that this was the usual police response to distributions other than the one held at 6:00 p.m. off the Rue des Verrotières. Eba J, a 15-year-old Oromo boy, told us:

The police come when the food is being handed out…. They are saying, ‘Don’t eat.’ They say, ‘Go, go, go.’ Even if I don’t get anything to eat, the police don’t care. They say, ‘Go, go, go.’ After that, they come with spray.[106]

French law provides that “any person who directly or indirectly facilitates or attempts to facilitate the entry, movement, or irregular stay of a foreigner in France will be punished by imprisonment of five years and a fine of €30,000.”[107] Nevertheless, there are several exceptions to this provision, including for individuals or associations that provide free legal assistance, food, shelter, or other forms of assistance “aimed at preserving [migrants’] dignity or physical integrity.”[108]

A 2013 EU directive on minimum standards for the reception of asylum seekers requires EU member states to provide “material reception conditions to ensure a standard of living adequate for the health of applicants and capable of ensuring their subsistence.”[109] Moreover, as the Lille administrative tribunal noted in its March order, the denial of food, water, and other basic necessities violates the prohibition on degrading treatment.[110]

IV. Police Harassment of Aid Workers

In addition to police claiming, incorrectly, that aid workers are breaking French law by distributing food aid and other humanitarian assistance, aid workers say they are regularly subject to document checks, a procedure that is not unlawful but is open to abuse.

When aid workers photograph or film police, as they are permitted to do under French law, they said police have at times seized their phones for short periods, deleting or looking through the contents without permission. On occasion, police have also destroyed food while searching vans or halting distributions.

Some of these actions, such as temporarily seizing phones and deleting footage, are clearly impermissible. Other actions, taken individually, are not: it is not improper for police to inspect vehicles and issue citations for infractions, and by law, individuals must submit to identity checks.

The circumstances in which these tactics are used, however, suggest that police are not employing them for public safety or other legitimate policing purposes. In many cases, the circumstances suggest that police engage in these acts to intimidate aid workers, or at the very least to create obstacles to the delivery of humanitarian assistance. Moreover, in combination, such policing practices bring the police force into disrepute.

In particular, police check aid workers’ documents with such frequency that there is little justification for the checks as a means of establishing identity. “They do ID checks all the time,” Loan Torondel, of L’Auberge des Migrants, told Human Rights Watch.[111] Other humanitarian workers told us that police sometimes subjected them to multiple identity checks during the same distribution. A law student volunteering with L’Auberge des Migrants said that in late May or early June:

We had two ID controls within one hour. It was the same situation, the same distribution, yet we had two ID controls.[112]

She added, “We asked the policeman to explain why he controlled us a second time. He didn’t give a clear answer; he said something about the state of emergency.” When she pointed out that police can only check documents for specific reasons set out in French law, the police officer eventually told them the second check was because the aid workers had “regrouped.” In fact, “the distribution was finished; we were in the van ready to go,” she told Human Rights Watch.[113]

Numerous humanitarian workers said that police officers addressed them by name when asking for documents, reinforcing the conclusion the checks were not intended to establish identity.

When police conduct document checks, they typically require everybody who is being “controlled” to remain in the same place until all documents are checked. This practice means that identity checks can be used as a means of delaying or even halting food distribution. In late June, for instance, a humanitarian worker said that when they attempted to start an evening distribution, “We were controlled for an hour. During that time, we couldn’t move. We just had to stand there waiting.”[114]

Document checks also prevent aid workers from observing how police treat migrants when they halt food distributions. Sarah Arrom, of Utopia 56, said that during a June food distribution, the police required them to stay around the trucks during a document check:

They used flashlights in our eyes so we couldn’t see what they were doing. They don’t like us to witness what they do. They really hate that.[115]

Some humanitarian workers said they have also been subject to pat-downs by police. Loan Torondel said:

This is something police can do if they have a good reason to think you might have drugs or arms on you. When they did it to me, I had just been distributing food.[116]

In response to these and other police tactics, some humanitarian workers have begun filming police conduct at food distributions. Noting correctly that French law does not prohibit filming police in public places,[117] a humanitarian worker said, “Even so, the police threaten us when we film them.”[118]

In one such case, in June, an officer with the riot police took a phone out of a humanitarian worker’s hand as she was filming. The humanitarian worker told Human Rights Watch that the officer initially refused to return her phone when she asked for it back. He looked through her photos before eventually returning it to her.[119] In other instances, humanitarian workers said that police had deleted videos and photographs on their phones before returning the devices.[120]

Police also frequently inspect all vehicles in areas where distributions are held, issuing fines for very minor infractions. “They’ll often say we parked the wrong way,” Sarah Arrom, of Utopia 56, told us. “We know that’s not the case, because we have to be very careful about those kinds of things.”[121] We also heard of fines for low tire pressure, dirt on mirrors and windscreens, and insufficient windscreen fluid, among other technical infractions.

On June 28, after police ended the evening distribution shortly after 8:00 p.m., a Human Rights Watch researcher observed as an officer issued two littering citations, each carrying a fine of €68, to a staff member of L’Auberge des Migrants, one of the organizations overseeing the distribution. When she objected that some migrants had left their food on the ground because police ordered them back into the woods, the police commissioner replied that he was particularly concerned for the health of the seagulls that might eat the food and said that she should consider herself lucky not to receive a citation for every box of food left behind.

Summarizing such reports, the French ombudsman observed in June:

When they try to set up facilities that should be set up by public authorities (showers, distributions of food and water), the associations are impeded and threatened: tickets for vehicles parked in front of the associations’ premises, orders for a long-established association kitchen to comply with [restaurant food preparation] standards, threats of prosecution for assisting people residing illegally [in France].[122]

Such interactions between individual police officers and humanitarian workers raise concerns that those individual police officers, at least, regard such tactics as a way to reduce the number of irregular migrants in and around Calais by impeding humanitarian activities. “The idea they have is it’s the volunteers who are causing migrants to come,” one humanitarian worker said.[123]

Identity checks are particularly open to abuse, as studies by the Open Society Justice Initiative and the French National Center for Scientific Research, the European Union’s Fundamental Rights Agency, and Human Rights Watch, among other groups, have found.[124]

The failure to carry an identity card is not in itself an offence in France, but police are authorized to detain a person for up to four hours to establish identity. French police are not required to offer any explanation for the stop, and they do not provide any written record of the stop.

Police in France have an obligation “to refrain from any act, comment, or behavior that could damage the reputation of the police or the gendarmerie” and should “take care not to harm the credit and renown of these institutions by their behavior.”[125] They should strive to “carry out their duties in a manner which is beyond reproach.”[126] The tactics employed by police in Calais do not meet these standards.

Assessing the range of policing tactics used against members of humanitarian groups, Sarah Arrom, of Utopia 56, said:

What we are doing is legal. The police can control our ID.... We never try to stop a police operation. We don’t interfere with their job. We respect their job. We ask that they respect our jobs.[127]

V. Police Abuse as Negative Factors in Asylum, Access to Child Services

Police abuse of asylum seekers and migrants is problematic in its own right, but it also has significant knock-on effects. When police abuse migrants, harass aid workers, and disrupt humanitarian assistance, they contribute to negative experiences and feelings of alienation, reinforcing practical barriers to seeking asylum.

Many obstacles exist to those in Calais who want asylum, including:

- Distance of asylum office: the office nearest to Calais is in Lille, 110 kilometers away. Many migrants cannot afford the cost of transport, and those who can risk detention if they travel by public transport. Asked whether local authorities would support the establishment of an asylum office in Calais, Vincent Berton, deputy prefect for Calais, said: “There is no obligation for the State to examine the asylum claim in Calais. Calais is not the most appropriate place. We do not wish to recreate a camp.”[128]

- Delayed appointments: After an asylum seeker indicates a desire to seek asylum, an association delegated by the French Office for Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons (Office français de protection des réfugiés et apatrides, OFPRA) should give the asylum seeker an appointment with the asylum office (guichet unique) within 3 to 10 days to register their claim. After this initial appointment, the asylum seeker should receive an asylum claim certification and has 21 days to submit a formal asylum application.[129] In reality, they usually wait between one and two months for the appointment, Human Rights Watch heard.[130] In the meantime, they remain in limbo—generally ineligible for accommodation in a reception center or for the monthly allowance (allocation pour demandeur d’asile) received by asylum seekers not housed in reception centers.[131]

- Lack of information: Some of the children and adults Human Rights Watch interviewed said that they did not know that they could apply for asylum in France. Some did not know what asylum was. Others replied with questions of their own about how to apply and what the benefits of asylum were.

For many asylum seekers and migrants, these barriers are compounded by the police.

Nearly all those whom Human Rights Watch interviewed who did not want to stay in France cited their treatment at the hands of French police as an important factor in that decision. “I love Paris. I love the French language. But no. The police here are very bad,” Layla A., an 18-year-old woman from Ethiopia, said.[132] Similarly, when we asked Biniam T., a 17-year-old boy from Ethiopia, if he had considered applying for asylum in France, he told us, “The way the police treat us is not good. France is not a good place for refugees.”[133] Meiga T., a 16-year-old Oromo boy, replied to the same question by shaking his head and saying, “The police spray. They say fuck off.”[134]

An independent inquiry conducted by British lawmakers and sponsored by the Human Trafficking Foundation found, in fact, that “the hostile actions of the French authorities [in Calais] have created a more immediate ‘push factor’ of trafficking to the UK.”[135]

Police mistreatment and abuses of asylum seekers and migrants can also adversely impact access to child protection services.

For unaccompanied children in Calais, the closest child protection shelter is in Saint-Omer, 45 kilometers away. The shelter generally places new arrivals in a facility located in a converted gymnasium, intended for use on an emergency basis, and a lack of space in the facility intended for longer-term use means that they may remain in the emergency facility for an extended period. “It should be a quick process for kids to get into the real child protection part of Saint-Omer. That isn’t happening. They can’t say when they’ll offer kids a place and provide them with a proper social and legal support,” Sabriya Guivy, legal adviser for Refugee Youth Service, told us.[136] The emergency facility offers little privacy and has no social workers or other specialized services.[137]

As a result, many leave the shelter after one or two nights. “They end up using it to take a break from sleeping in the woods,” another humanitarian worker said.[138]

Sabriya Guivy told Human Rights Watch that child protection authorities fail to understand why many children leave the shelter after short periods. “Their idea is that the unaccompanied kids don’t want to be protected. But the authorities aren’t actively fulfilling their duty of care,” she said.[139]

Outside regular business hours, the police are responsible for arranging transfers to the shelter and may hold children overnight at the station, something that deters children from seeking a place in the shelter. “They [the unaccompanied children] don’t see the police as their friends,” a humanitarian worker told us.[140]

As the French ombudsman noted in a June 14 statement, “being put in the care of child welfare services implies, in the evening and at night, going through the police station, so this procedure is a particularly strong deterrent.”[141]

Aid groups report that police sometimes refuse outright to arrange for transfers. On June 30, for example, when two humanitarian workers approached the police commissioner at the end of a midnight food distribution to request assistance for a 16-year-old boy who asked to go to the shelter, the commissioner denied their request.

In the presence of two Human Rights Watch researchers, he stated that he would not arrange the boy’s transfer because he did not believe the boy was under 18. When a humanitarian worker reminded him that age assessment was not his responsibility and that authorities were obligated to give the benefit of the doubt in close cases, he repeated that he did not believe that the boy was 16 and would not arrange for the boy’s transfer to the shelter.

Aster N., a 17-year-old Ethiopian girl, said: “Someone who is underage can’t think things through like a mature person. They can’t protect themselves physically or mentally. They need support.”[142]

Acknowledgments

This report was written by Michael Garcia Bochenek, senior counsel on children’s rights at Human Rights Watch, based on research he undertook with Helen Griffiths, children’s rights coordinator; Bénédicte Jeannerod, France director; and Camille Marquis, senior advocacy associate, in June and July 2017. Victoria González Maltes, intern in the Paris office, provided research assistance.

Zama Neff, executive director of the Children’s Rights Division; Judith Sunderland, associate Europe and Central Asia director; Aisling Reidy, senior legal adviser; and Danielle Haas, senior editor, edited the report. Bill Frelick, refugee program director, and Bénédicte Jeannerod also reviewed the report. Michelle Lonnquist, associate; Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, and José Martínez, senior coordinator, produced the report. Zoé Deback translated the report into French, and Camille Marquis reviewed the translation.

We appreciate the willingness of the directorate of asylum of the Ministry of the Interior in Paris and of Vincent Berton, deputy prefect for Calais, to meet with us to discuss our findings prior to this report’s publication.

Human Rights Watch is particularly grateful to the nongovernmental organizations and individuals who generously assisted us in the course of this research, including Margot Bernard, Loan Torondel, and other staff and volunteers of L’Auberge des Migrants; Evelyn McGregor, Dunkirk Legal Support Team; the staff and volunteers of Gynécologie Sans Frontières; Annie Gavrilescu and other staff and volunteers of Help Refugees; Madeleine Harris, Humans for Rights Network; Médecins Sans Frontières; the Plateforme de Service aux Migrants; Micaela Bogen and other staff and volunteers of Refugee Info Bus; Sabriya Guivy, Michael McHugh, Sandy O’Brian, Arthur Thomas, and other staff and volunteers of Refugee Youth Service; Vincent de Coninck and other staff and volunteers of Secours Catholique; and Sarah Arrom, Gael Manzi, and other staff and volunteers of Utopia 56, as well as the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Finally, we would like to thank the many children and adult refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants we interviewed.