2. What has the LRA been fighting for all these years?

3. What is the US Counter-Lord’s Resistance Army Operation and why does it exist?

4. How many LRA members remain and where are they now?

8. What should the RCI-LRA do now that the US is pulling out its troops?

10. What should happen with the pending ICC arrest warrant for LRA leader Joseph Kony?

The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) is a Ugandan rebel group led by Joseph Kony. The group originated in 1987 in northern Uganda among ethnic Acholi communities. The Acholi suffered serious abuses at the hands of successive Ugandan governments in the turbulent 1970s and 1980s. Kony, an Acholi himself, and the campaign against the government of Uganda initially had some popular backing, but support waned in the early 1990s as the LRA became increasingly violent against civilians, including fellow Acholi. The group abducted and killed thousands of civilians in northern Uganda and mutilated many others. The brutality against children was particularly severe. Various military campaigns against the LRA eventually pushed the group across the border into southern Sudan (now South Sudan) and, in 2005 and 2006, into the Democratic Republic of Congo where they remained active for several years. The LRA has crossed in and out of the Central African Republic since 2008. Although the LRA is no longer based in northern Uganda and has significantly decreased in size, the group continues to commit abuses – though at a much-reduced scale – against civilians in the remote border area of Sudan, South Sudan and the Central African Republic, southeast Central African Republic, and the border areas between Congo and the Central African Republic.

In 2005 the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague issued arrest warrants for war crimes and crimes against humanity for the LRA’s top five leaders at that time: Joseph Kony, Vincent Otti, Okot Odhiambo, Raska Lukwiya, and Dominic Ongwen. The warrants were made public in October 2005. Lukwiya was killed in 2006 and Otti in late 2007. Odhiambo’s body was found in the Central African Republic in early 2015.

On January 6, 2015, US military advisers working with the African Union Regional Task Force in the Central African Republic received Ongwen into custody. He was eventually transferred to the ICC.

Kony remains at large. He has been thought to be hiding in Kafia Kingi, in Darfur, Sudan. However, recent reports indicate that he may have been moving through the Central African Republic as recently as March 2017.

2. What has the LRA been fighting for all these years?

According to former LRA fighters, Kony’s stated goal has been to overthrow Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni and establish a government based on Kony’s interpretation of the bible’s Ten Commandments. Since the LRA no longer operates in Uganda, the group’s current political goals are not clear. Kony’s tactics in recent years appear aimed largely at ensuring his survival and to a lesser extent, the survival of some senior LRA leaders, though there has been dissent in his ranks.

3. What is the US Counter-Lord’s Resistance Army Operation and why does it exist?

In 2009, bipartisan legislation was introduced in both houses of the US Congress. After significant advocacy from US-based groups who sought an end to the protracted conflict, in May 2010 President Barack Obama signed into law the LRA Disarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery Act. The act called on the US government to develop a comprehensive strategy to protect civilians and to work with the governments in central Africa to “apprehend or otherwise remove from the battlefield” LRA leaders. In November 2010, President Obama published his strategy, which outlined four primary goals for US engagement with the LRA crisis, including stopping LRA leaders, protecting civilians from LRA attacks, encouraging escape and defection from the LRA, and providing humanitarian assistance to affected communities.

Initially the US assistance was mostly logistical and intelligence support to the Ugandan armed forces. Eventually, in 2011, the African Union’s Peace and Security Council authorized the Regional Cooperation Initiative for the elimination of the LRA (RCI-LRA) which included the Regional Task Force (RTF), as the military component. While the AU’s RTF drew its operational forces largely from the Ugandan army, in 2013 the US also trained Congolese military personnel dedicated to the RTF. The US announced in October 2011 that it would send 100 US Special Forces personnel as military advisers to the Ugandan army and other armed forces in the region to assist in apprehending LRA leaders. In recent years and as the LRA has shifted its primary location, many US military advisors and Ugandan army soldiers deployed to the RTF have been based in southeastern Central African Republic, despite some continued, smaller-scale attacks by the LRA in neighboring Congo and South Sudan.

The US has spent more than $ US 780 million on anti-LRA activities since 2008. In addition to military support, the US has provided humanitarian assistance to communities affected by the LRA, both in northern Uganda and other countries where the LRA operates. The US also supported the development of early warning networks and infrastructure rehabilitation such as erecting mobile phone towers in key town centers in northern Congo’s Haut Uele and Bas Uele districts and support of similar warning networks and community radio projects in the Haut Mbomou and Mbomou provinces in the Central African Republic.

4. How many LRA members remain and where are they now?

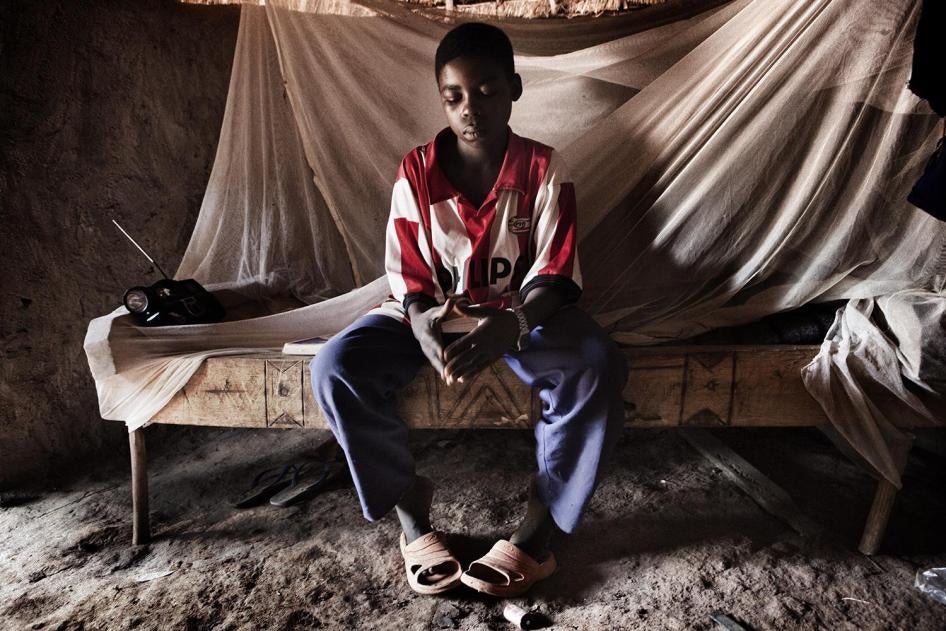

It’s not known exactly how many LRA members remain active but those interviewing defectors estimate there are about 120 remaining, with roughly 80 fighters carrying arms. Numbers of abducted civilians and children born into captivity have varied over the years, but are currently estimated to be approximately 80-100. Splintered groups of LRA members are believed to be moving between the Kafia Kingi enclave of Darfur, Sudan and Haute Kotto, the Central African Republic.

5. What have the Counter-LRA efforts meant for people in southeastern Central African Republic and other LRA affected areas?

The presence of Counter-LRA forces in southeastern Central African Republic has had a positive effect on general security for civilians in the region. The Central African Republic has been in crisis since late 2012, when mostly Muslim Seleka rebels began a military campaign against the government of Francois Bozizé, seizing the capital, Bangui, in March 2013. Their rule was marked by widespread human rights abuses, including the wide-scale killing of civilians. The presence of Ugandan and US forces in the southeast contributed to preventing the Seleka from reaching that area in mid-2013. Later in 2013, the Christian and animist anti-balaka militia organized to fight the Seleka. Associating all Muslims with the Seleka, the anti-balaka carried out large-scale reprisal attacks against Muslim civilians in Bangui and western parts of the country. The center and west of the country spiraled into chaos, and today there is acute violence in the country’s Ouaka, Haute-Kotto provinces and western parts of the Mbomou province.

Towns where there is a Ugandan or US military presence have been some of the most stable areas in the Central African Republic over the last four years, despite limited government control of the area. Keeping armed groups like the Seleka out of the southeast has been a positive, if indirect, benefit of the AU’s RTF.

6. Why did the US pull out and what does the withdrawal mean for people in the Central African Republic, South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo?

The United States has provided the most support of any government in the effort against the LRA by countries in the central African region. On March 29, the US announced that it would end the Counter-LRA operations, due the fact that the LRA has been severely weakened. The mission’s cost was also a factor in ending operations. The Ugandans also announced their withdrawal. In May, security in the southeast was formally handed over to forces from the Central African Republic.

LRA attacks on civilians are at lower levels than in previous years, and defections have drained the LRA of manpower. But in many ways, the withdrawal could not come at a worse time for civilians in southeastern Central African Republic, as it runs the risk of worsening an already precarious security situation. In late 2016 the Seleka split into several factions, some allying with anti-balaka groups, and started to fight among themselves. This violence has resulted in the killings of hundreds of civilians, at least, in the center of the country. In March the violence spread east to areas that had been stable for years. Two towns north-west of Rafaï in the Mbomou province, Bakouma and Nzako, saw intense fighting between Seleka groups and serious human rights violations perpetrated against the civilian population. In May, at least 100 were killed after intense fighting in Bangassou, in the Mboumou province.

The withdrawal of Ugandan and US forces means that Seleka fighters may be emboldened to move into areas they once feared to tread. Conflict could spread to Rafaï, Zémio, Djéma and Obo, towns that, until now, had been spared the violence that has engulfed the country over the last four years.

Seleka groups have no qualms about making alliances with former enemies – as shown by the alliance between one faction and anti-balaka groups in the center of the country – and the Seleka have been in contact with the LRA in the past. If it was in their interests, Seleka groups could potentially align with the LRA and help them reconstitute their forces. No matter what occurs regarding these groups, civilians in southeastern Central African Republic will remain vulnerable to attacks from various armed groups, as there is little security or effective governance in the area.

In neighboring war-torn South Sudan, the security vacuum created by the withdrawal of the Counter-LRA forces could encourage southern Sudanese rebels to move into and operate out of eastern Central African Republic. The government’s Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) forces could move into the area and replicate the abusive scorched-earth counterinsurgency strategies that they have pursued in southwestern South Sudan since late 2015.

Meanwhile, the withdrawal of US forces may also have an adverse impact on the volatile security situation in northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo. LRA splinter groups as well as South Sudanese armed groups, poachers and bandits continue to attack the local population in this isolated and underdeveloped region. Large-scale abductions, primarily for short periods of time to carry looted goods, and ambushes remain frequent occurrences. The influx of tens of thousands of refugees fleeing conflict in the Central African Republic and South Sudan over the past year have added further strain on Congolese communities.

7. What should the US put in place before it completes its withdrawal to improve the potential for security in the region?

The US and Ugandan pullout will leave a security and protection vacuum in southeastern Central African Republic, leaving civilians vulnerable to the risk of that various armed groups could seize control and commit abuses against them. Due to and depending on multiple factors, the potential revitalization of the LRA remains a possibility.

Currently the only force with any capacity to secure towns and villages for civilian protection is the United Nations peacekeeping mission, the Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic, also known as MINUSCA. The mission took over from an AU mission in 2014 and has 12,870 forces, but it is overstretched with the fighting in the center and northwest of the country.

MINUSCA has a presence in Obo, where Counter-LRA activities in the Central African Republic are based, but it does not currently have the logistics or manpower to monitor the whole region as the Ugandan and US militaries did.

The Central African army, known as FACA, disbanded when the Seleka took power and has been reconstituting itself over the past few years with international support. Two battalions have been trained by the European Union, one of which took over for the Ugandan military in Obo. However, questions remain as to the battalion’s level of preparedness.

The US has made statements that it will continue training national forces that continue to search for the LRA, like the FACA, but to date there are few details as to how this would be conducted and there are concerns that doing so would run afoul of US law, given the FACA’s history of abuse.

To prevent the southeast from becoming engulfed in the country’s broader violent conflict, the US should take several initial steps. First, it should hand over materials such as vehicles and buildings used in the Counter-LRA effort to MINUSCA, enabling the mission to be ready to respond to any violence or attacks. Second, it should articulate how it will conduct training for FACA troops, assuming they pass required human rights vetting procedures, and begin this training immediately. Finally, it should recommend the troop ceiling for MINUSCA be raised, allowing the mission to find manpower to fill the void in the southeast.

8. What should the RCI-LRA do now that the US is pulling out its troops?

On May 12, the Peace and Security Council of the African Union renewed the mission’s mandate until May 2018. However, until there is international financial support, the military component of the RCI-LRA is over. Uganda has already sent many troops home.

The Ugandan forces leave behind a mixed legacy. While they were instrumental in helping to secure the region, allegations of crimes committed by Ugandan troops, including sexual abuse, remain unaddressed. With or without African Union hatted soldiers on the ground, it is critical that civilians in the Central African Republic who feel they have been aggrieved by soldiers operating under the Regional Task Force have access to justice and remedies.

Human Rights Watch is particularly concerned about on-going allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse as well as sexual violence by Ugandan soldiers deployed in southeastern Central African Republic. The United Nations Secretary-General’s 2003 Bulletin on protection from sexual exploitation and abuse states that exploitation involves situations where women and girls are vulnerable and a differential power relationship exists. Exploitation is “any actual or attempted abuse of a position of vulnerability, differential power, or trust, for sexual purposes, including, but not limited to, profiting monetarily, socially or politically from the sexual exploitation of another.”

Human Rights Watch has interviewed 16 survivors in Obo, some of whom had a child or children with Ugandan soldiers who have since left. Most of the women we interviewed were involved in sex-for-money or food schemes and were encouraged to be a Ugandan soldier’s “local wife.” Multiple women and girls said they were promised they would be taken to Uganda when the soldier’s rotation was finished. In many of these cases, sexual relations occurred on the Ugandan base. Women and girls said that Ugandan soldiers had threatened them not to talk to United Nations or Ugandan investigators.

Some survivors nevertheless tried to file a complaint at the Ugandan base and seek assistance in Obo. Three women and one girl said their allegations were ignored, while one woman said she received small amounts of food and medicine for a limited period.

According to available information, Ugandan investigators interviewed at least six survivors in the past year, but those survivors told Human Rights Watch that there has been no follow up or subsequent communication. The survivors said they had no means with which to contact the investigators.

The Ugandan military has announced investigations into these allegations.

Ensuring that these cases are properly investigated and addressed and that civilians negatively affected by the Counter-LRA operations have access to justice mechanisms and redress – despite the withdrawal – remains critical.

9. What should the European Union and the United Nations do now that the US is pulling out its troops to ensure civilian protection?

In the Central African Republic, MINUSCA is the only force capable of addressing the threat posed to civilians by the LRA and spillover of violence into the south-east from the Ouaka, Haute-Kotto and Mboumou provinces. MINUSCA is mandated by the UN Security Council to protect civilians throughout the territory of the Central African Republic and has a crucial responsibility in this regard. It should use the Ugandan and US withdrawal to justify raising its troop ceiling to account for the loss of these international forces. In the meantime it will have to use a force that is already stretched too thin.

The European Union has provided critical support and training to the FACA. This support should continue to enable the Central African forces to eventually address insecurity by armed groups on its territory.

If AU states can propose a strategy to arrest Kony, countries sould consider supporting such a plan.

10. What should happen with the pending International Criminal Court arrest warrant for LRA leader Joseph Kony?

Joseph Kony is charged with 12 counts of crimes against humanity and 21 counts of war crimes committed in northern Uganda after July 1, 2002, and his forces are implicated in many other grave crimes committed across central Africa.

Kony should be arrested and surrendered to the International Criminal Court (ICC) to face the charges against him.

The drawdown of the Counter-LRA Operation poses new challenges to Kony’s arrest as the resources and expertise from the operation will no longer be available to facilitate his surrender. While views are mixed on the impact of the operation to date, it is notable that Dominic Ongwen came into the custody of US forces in the operation and was then transferred to the ICC in 2015.

States that are committed to justice for Kony’s alleged crimes will need to work together to develop a strategy for advancing Kony’s arrest in the absence of the Counter-LRA Operation.

ICC states parties that are donors in the region—such as France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, along with the European Union and the United States—should take the lead in such efforts in close collaboration with regional governments.

The strategy should include plans for continued coordination among forces in the region to advance surrender, while respecting and promoting protection of civilians, and support for such efforts. It should also include diplomacy with regional governments where Kony may be located or moving around in to highlight the continued importance of his surrender.